- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

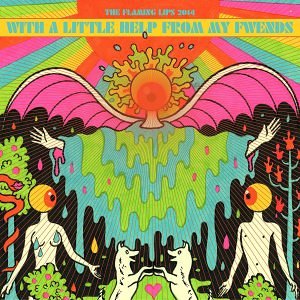

NANCY CARR * With a Little Help from My Fwends, the Sgt. Pepper’s tribute album from the Flaming Lips and a bunch of their buddies, is a frequently painful listening experience that is also revelatory. It’s just that much of what it reveals leads to depressing conclusions about how the 21st century is shaping up.

This is a true cover album, in the sense that Booker T. and the MG’s McLemore Avenue is, and that Mojo magazine compilations of various people doing songs from Revolver or Yellow Submarine aren’t. That is, it represents a genuine effort to reimagine the work and stamp it with a new personality. And if there’s one thing With a Little Help from My Fwends is, it’s of its time; the spine of the album appropriately puts “2014” next to the title. The album’s keynotes are fragmentation and dissonance, both within songs and between them, producing an effect quite different from the musical variety of the Beatles’ album. By my count, three songs rise above the often gimmicky technological effects that gum up the works and achieve emotional resonance. As a whole, though, the album replaces the Beatles’ (tragically naïve) faith in the transformative power of drugs with mere trippiness, and their (sometimes satirical, sometimes sympathetic) engagement with the world with cynical weariness. I was only one year old when Sgt. Pepper’s came out, but listening to With a Little Help from My Fwends the sense of loss I feel for what was imaginable at that time is personal.

You know the worst of what you’re in for from the start, at least: “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” and especially “With a Little Help from My Friends” are a hot mess. Both songs credit three artists or groups, and both suffer from throw-everything-at-the-wall syndrome. The opening track leaches all the power out of the original by largely dropping out the rhythm section, changing tempo repeatedly, and drowning the ending in a guitar solo by J. Mascis that is mixed up so high it leaps out the way cheap commercials go up in volume during TV shows. “With a Little Help from My Friends” is aggressively unlistenable. It sounds like a parody to me, but one without a clear point. It kicks off with a messy, overlong drum solo, and the vocals are literally all over the place—alternately strident, deliberately out of tune, and so processed they sound robotic (there will be way too much of this last later in the album).

Yet this track is the key to the album’s strength, as well as its weakness. The Lips and friends here serve notice that this won’t be a forgettable by-the-numbers cover version, like Cheap Trick’s Sgt. Pepper’s Live; it will show artists’ genuine responses to the Beatles’ songs. Thus I believe the mess of “With a Little Help from my Friends” points to acute discomfort with the vulnerability and hope that underlies the song. The Beatles’ original is both a tongue-in-cheek salute to the music hall tradition and a sincere statement about friendship, thanks largely to Ringo’s lead vocals and the band’s call and response with him. What With a Little Help from my Fwends as a whole ends up demonstrating most powerfully is that the delicate balance of humor, optimism, realism, and empathy that shaped “Sgt. Pepper’s” is impossible to recapture in the 21st century.

But boy, does this album turn the trippiness up all the way up to 11. “Fixing a Hole” by the Electric Wurms and “Within You Without You” by Birdflower, the Flaming Lips, and Pitchwafuzz are convincing musical acid trips. “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” by The Flaming Lips, Miley Cyrus, and Moby, manages to combine trippiness with emotional power, mainly because the arrangement stays rather closer to the Beatles’ original and the vocals are not as overprocessed as elsewhere. On the other hand, “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”, by The Flaming Lips, MJ Keenan, Puscifer and Sunbears, feels simply disjointed and tedious.

“She’s Leaving Home,” by Phantogram, Julianna Barwick, and Spaceface, marries 1980s-style electronics, including drum machine effects, to a lead vocal that retains the human investment of Beatles’ version. This is a cover that sets its own terms but also relates meaningfully to the original, a distinction shared on this album by “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “A Day in the Life.” By way of contrast, “When I’m Sixty-Four,” by Def Rain, The Flaming Lips, and Pitchwafuzz, is an unmitigated disaster. Most of the vocals sound like they’ve been filtered through a 1980s Vocoder (remember those?), and the instrumentation is so heavy on bloops and bleeps that it sounds like the track was recorded at that cantina in the original Star Wars. The whole has all the feeling and humor of the automated voice you get when you call information.

“A Day in the Life,” by the Flaming Lips, Miley Cyrus, and New Fumes, is, like “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” a version that hews more closely to the Beatles’ original; the changes it does introduce, of tempo, instrumentation, and vocal inflection, work with the elements of that original rather than fighting with them. It’s not accidental that Coyne and Cyrus are the singers on both songs: along with Julianna Barwick on “She’s Leaving Home,” they’re the best vocalists on the album.

For me the album’s most telling moment is the end of “A Day in the Life.” The music stops abruptly, there’s a second or so of (to me at least) unintelligible talk from Cyrus, and that’s it. On “Sgt. Pepper’s” the Beatles famously used the studio itself as their instrument; on “With a Little Help from my Fwends” the Lips and Co. use much more advanced musical technology to achieve far less. It’s fitting that the album ends not with the Beatles’ bang but with a whimper. But an honest whimper, be it noted.

One thing listening to “With a Little Help from My Fwends” did for me was enhance my appreciation of the talents of Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr, as well as of George Martin and Geoff Emerick. First, the singing: no one on “Fwends” comes anywhere near the beauty and depth of Lennon’s singing, and it’s telling that the most powerful songs on it retain his vocal touches (the “bye bye” at the end of “She’s Leaving Home,” the intonation of “Oh boy” on “A Day in the Life.”) No one matches McCartney’s singing on the album, either: not his punch (the triumphant soaring of the chorus of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”) or his cheeky humor (“Lovely Rita”). And there are no harmonies on the album worthy to set beside Lennon’s and McCartney’s.

As for the rhythm section, it’s mostly minimal, electronic, or buried way down in the mix on Fwends, which makes re-listening to “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” an absolute revelation. It’s McCartney’s muscular, melodic bass work and Starr’s steady beat and inventive fills that propel the album and give it its kick. The cymbals and rat-a-tat drumming on “Mr. Kite!” and the three bass drum beats before the first chorus of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” make those songs in ways I never fully recognized before. And McCartney’s work on bass throughout the album is crucial to its sound: his lines are always percolating beneath the surface, adding body, melodic interest, and momentum.

Finally, Harrison’s respect for Indian instrumentation and earnest spiritual seeking imbue his version of “Within You and Without You” with a piercing sincerity that shames the cover on Fwends. And George Martin’s arranging/producing work, along with Geoff Emerick’s engineering chops, make every part of the original album sound inevitable and perfectly placed. Sometimes, as Joni Mitchell put it, you don’t know what you’ve got til its gone.

I haven’t listened to this yet, and may never, but it seems odd that Wayne Coyne would do it. He is a good front man in a carnival barker sort of way, but his singing voice isn’t great. He does himself no favors by inviting direct comparison to Lennon and McCartney. As with most Fab covers projects, I have little interest. The upcoming Macca tribute seems like it might be more worthwhile than this mess, though. Another quick point about Sgt Pep vs. modern music: the Beatles records had actual dynamics and a sense of space. It wasn’t all dense and super-saturated. Some of it was, but the Beatles psych stuff was actually kind of minimal, mostly just piano, bass and drums with some acoustic and maybe a guitar solo and some string parts, maybe. Food for thought.

Not popular to say, but I think it’s time to acknowledge that pop music isn’t attracting top-level creative people anymore. Yes, there are a few geniuses, but in general the aggregate brainpower of the people doing this kind of art has steadily decreased since the Beatle era. That’s why this blog is about a group that broke up 44 years ago.

There was a general shift from rock to comedy around 1970; and from comedy to tech around 1985; I guess it’s still in tech? But the juice isn’t in rock anymore, that’s for sure. That’s why you have this record, and why (from Nancy’s description) it seems to suck.

Over the past few years, those with the highest intelligence in contemporary society have gravitated towards writing Beatles blogs.

Thank God, @Dan, someone noticed! 🙂

Point taken, ouch, but at the same time, I think there’s a valid point in here: certain industry/artforms seem to reach a kind of cultural critical mass, where they become prominent and in that prominence attract the next generation of talented young people to work in that industry/artform. And it’s that influx of talent that gives industries/artforms their Golden Ages. Now, if you’re one of those people who denies the existence of Golden Ages, we’re not on the same bus to begin with. I personally do think there are times where certain forms are better, and times when they are worse — defined however you like.

Rock from 1963-75 or so was in a Golden Age; the inciting event was The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, which inspired a massive number of kids to pick up guitars. At this point the “million monkeys with typewriters” effect comes into play. Comedy did the same thing about ten years later, and while there was no single event, there were the presence of a handful of contemporaneous geniuses that transformed that art from schtick into the thing lots of smart kids (myself included) wanted to do.

It goes geniuses –> mass appeal/million monkeys –> lots of that artform, some of it really good –> diminishing returns –> eventual cultural fatigue –> “where are today’s geniuses” –> geniuses found –> mass appeal/million monkeys…

This ebb and flow is obvious, but it’s not often expressed because it doesn’t help anybody make any money. People are divided into generations and then convinced that the culture aimed at them is an expression of their identity. This is why, for a contemporary teenager, liking the Beatles is a subversive act. I heard this constantly at the Fest for Beatles Fans.

Speaking as a working pro, comedy today simply is not as good as it was in 1975. It’s more knowing but less smart, glossier but less ambitious, higher tech but less innovative, swearier but less anarchic; people in comedy in ’75 thought the right comedy might change the world (just like people in rock in 1965 did). Not today. Some of this is the people in it now (people who probably should’ve been lawyers or doctors or any one of a million more useful professions), and some of it is that you can only lose your virginity once. Once “Tomorrow Never Knows” is made, it’s made.

But I think one thing is undeniable: the post itself is proof of my point. Contemporary bands covering Pepper is as if The Beatles released an album of WWI ballads — which strikes us as absurd because the Beatles would’ve never looked in the rearview like that, and to the degree that they did embraced Victoriana/music hall, they so utterly made it their own that we no longer call it Victoriana/music hall, we call it Sgt. Pepper. (Or “Paul’s granny music,” if you’re a Lennonite.)

I don’t think there’s anything wrong or unfair in looking at the current state of an industry/artform and saying, “It’s in a down period.” That is, the brains are going elsewhere for the time being.

I wasn’t belittling this blog, it was meant to be a tongue-in-cheek compliment!

A good way of thinking about it is – “where do the weirdos go?” The misfits who can’t do much else? In the 60s and 70s they went into music, in the 80s and 90s they went into comedy, today they sit at home and express their weirdness online. Today’s teenage John Lennon is making sick jokes on 4chan and writing trolling comments under the youtube videoblogs of today’s teenage Paul McCartney.

Thank you, @Dan! Compliment taken. If you want Dullblog to be really good, go stand outside Devin’s apartment with a picket sign: “POST MORE”. 🙂

I think you’re right on about the weirdos. Wherever bohemians alight, twenty years later transforms our culture.

The problem is, today’s teenage John Lennon has no constructive way to turn that angry, funny trolling into fame and fortune. “Daily Howl” as a webcomic? Cartooning’s all right, John, but you really truly WON’T make a living with it.

The move from culture into tech is being forced, because free content turns writing/drawing/video into a hobby. Money, girls, adventure, a life — that’s what got Lennon out of his bedroom at Mendips and onstage and thence to Hamburg.

Lennon simply didn’t have the brain of a coder; he wasn’t entrepreneurial; he wouldn’t even end up at Pixar, because he couldn’t stay in art school. Even if he’d manage to make a new Beatles, the economics facing him once he got there would be much more onerous and uncertain than those in 1962 — unless he parlayed his group’s success into a label or site or something substantial that could be owned and grown and sold; and we saw what happened when The Beatles tried to do that.

My point is: I think the world has become much much harder for eccentrics of all types, especially those with a gift for creating rather than packaging, marketing, or promoting.

Your comments about the challenges facing a modern-day John Lennon reminded me of this clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZYXOSvpYQ0