- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

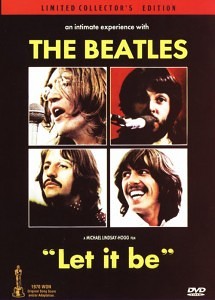

Is Mike man enough to withstand the awesome depressive POWER of this film?

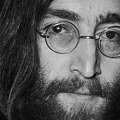

Last Thursday I happened to rent a DVD of “Let It Be,” and I did so mostly out of surprise that it was on the shelf at all. I’d seen it only once before, in the summer of 1981, paired with “A Hard Day’s Night” at the pot-scented Tivoli Theatre in St. Louis. Maybe it was Lennon’s recent death, or having watched the young Fabs in full flood directly before, but I still remember the funereal aspect of the evening’s second half, something even the sweet smell of demon weed couldn’t dispel. Big, grainy pictures of the Beatles with acne, smoking endless cigs and looking bored, running through some of the weakest music in their catalog. I remember everybody leaving the theater really down. A Beatle downer is the worst kind of downer, because it suggests that nothing is immune.

But I’m a tough old meditating bird, comfortable with the impermanence of things and the unsatisfactoriness of life—was I going to let a little Beatle-dukkha get in my way? No I was not. So I popped the movie into my computer and watched it.

While it was less of a downer than I remember, I need to say something: “Let It Be” is a shitty movie. Well, okay–maybe that’s too harsh. But it certainly is a missed opportunity.

I’m not saying this because it shows the Beatles fighting—that was the kind of opportunity any filmmaker with kill for. The implosion of the world’s greatest band, right before our eyes? THAT’s a documentary! No, I’m judging it on the terms “Let It Be” set for itself—a record of The Beatles in the studio, in 1969, preparing for a performance and making an LP. In this, it fails miserably.

That story—or any other story—is never explicitly stated. We are simply plopped into a soundstage, who knows where, who knows when, who knows why. The cameras are turned towards the Beatles, and let run; no context is given for any of their actions or dialogue. No nitty-gritty planning sessions are shown; no mixing or sequencing or playback; we learn nothing about how the Beatles actually made their songs, or made their albums. We don’t see, for example, John and Paul working on anything much together; we see George and Ringo working through “Octopus’ Garden,” which wasn’t even on the album. From “Let It Be” you’d think they just played a bunch of oldies, made a couple suggestions, ran through a few new tunes, and sent the results to EMI.

It’s as if the Beatles rehearsing should be fascinating enough; and though occasionally it is (when they’re really having fun, jamming on a song), most of the time any drama is external, supplied by the modern fan’s knowledge of the chronology—what happened before and after, and what it all meant. The “infamous” exchange between Paul and George takes place mostly off-mike, in whispers, and if you were ignorant of the larger narrative, it might not even register.

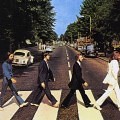

There’s no sense of stakes, no beginning, middle or end. There’s no sense of goals reached (or not reached), externalized conflict, or pressure to perform (which must’ve been immense). Each Beatle isn’t sketched as a character, given his own background or desires. It’s literally just four very famous, very charismatic guys playing their instruments and saying things to each other for an hour, then they go up on the roof and play, and then it ends.

“Let It Be” is a downer, not because it shows the Beatles breaking up, but because it doesn’t show the Beatles breaking up. It doesn’t show their creative process. It doesn’t show them making a new album, and failing. It’s a downer because it works so hard not to show any of these things. It’s a downer because the only thing it allowed itself to show—the Beatles horsing around like a quartet of old schoolchums—was the least real, least honest, least interesting thing that was going on in January 1969, the least interesting thing it could possibly show.

• • •

Imagine, if you will, a “Let It Be” that really delivered. And all you would have to do is structure it like a proper documentary.

[VO, with still images and footage.]

“In late 1968, the world’s most popular and respected rock group finished its most ambitious project,” says the voice-over. “Called ‘the White Album,’ it was a worldwide smash, and further cemented The Beatles as the preeminent musical talents of their generation. But the sheer effort of this two-record, 30-song statement took a dreadful toll on the four musicians and everyone around them: for the first time in the history of the group, a Beatle quit. And it was the least likely candidate, too–the drummer, Ringo Starr, the group’s peacemaker, left in July 1968, only to be wooed back with flowers. George Martin, the quartet’s longtime producer, wasn’t so easily swayed; he grew so tired of the grueling, acrimonious sessions that he eventually refused to take part.

“The expected response to such an effort–and the intergroup turmoil that surrounded it–would’ve been to rest. Take a month off, or six. But the Beatles, encouraged by the workaholic Paul McCartney, did the exact opposite: they decided to head into the studio as soon as possible, ringing in the last year of the Sixties with a new album. The album would be recorded live, with no overdubbing, to capture a raw, natural feel. There was even talk of heading back out on the road, something they hadn’t done since the days of the mania. Perhaps in small clubs, incognito, just to see if they still ‘had it.’ Or on a ship at sea. Or in a Roman amphitheater in North Africa.”

[Camera on Paul.]

Voice-Over: “So why aren’t you taking a rest? Are you afraid people will forget about The Beatles?”

Paul: “Of course not, it’s just that–we like to work. Being Beatles is what we are, y’see. We could stop for a while and say, ‘I’m just Paul for now,’ and work on–well, who knows what we’d work on, that’s the problem. We’d probably all just go on writing songs anyway.”

VO: “Do the others agree with you?”

Paul: “I dunno, you’d have to ask them. I think they do.”

[Camera on John and Yoko.]

VO: “John, do you want to do another album so soon after the double LP?”

John: “Not really. I think Paul feels the need, but I–we’re–quite busy with other things. I’m just doing a gig with the Stones, a melting of the minds which will be on a television near you someday I hope. And Yoko and I are working on several new albums, and our films, which we’ll put out eventually. And there’s sleeping, which I quite enjoy.”

And so forth. With limited voice-over to give context, cutaways to individual band members giving their opinions about what’s going on, and a chronological structure, the natural drama of the footage would be unlocked, and “Let It Be” could exist as a piece of filmmaking, not as a weird mound of cinema verité showing the mark of too many hands.

Of course, the flaws are intentional. From the moment the vibes turned out to be bad, everybody involved was scrambling to save face. It’s a movie by committee, and that’s why it’s never been re-released. But there’s a great film in there, a great documentary. All it needs is a little structure, and a re-cut, using footage we know exists, the stuff that really shows the tensions in the band, that really conveys what it was like in that room, with those people. Not Paul blinking meaningfully at the camera with his big saucer eyes, working hard to put a ballad over. That’s OK, because that’s who Paul was and is; but if you have that and not John and Yoko being their weirdo selves, and George smoldering and taking swings at John, and Ringo steadily getting more fed up—you don’t have the super-volatile, super-interesting mix of personalities and quirks that was The Beatles.

“Let It Be”‘s flaw isn’t that it showed the Beatles with their trousers off; it’s that it tried to make them all smooth down there, like Ken dolls. That’s how you turn the slow-motion implosion of the greatest rock band ever into something that wears out the fast-forward button.

• • •

This wasn’t the post I intended to write, this was what came out when I fired up WordPress. I was intending to write how odd it felt, remembering the first time I watched this movie, how they all seemed impossibly old and wise and accomplished. They were in their late 20s, and I was merely 12, and their weariness made sense to me, under such a pile of years. Now, at 44, everyone in “Let It Be” seems impossibly young, and in their actions I see all the impulsiveness of youth, and certainty, and hubris. Maybe that would’ve been a better post, but I’m too tired to write it. Which is so very “Let It Be,” isn’t it?

Nice reflection on how to experience a for decades no unrereleased failed Beatles movie.

“Let It Be” is a downer … because it doesn’t show the Beatles breaking up. It doesn’t show their creative process. It doesn’t show them making a new album. It’s a downer because it works so hard not to show any of these things. It’s a downer because the only thing it allowed itself to show… was the least real, least honest, least interesting thing that it could possibly show…

“Let It Be”‘s flaw isn’t that it showed the Beatles with their trousers off; it’s that it tried to make them all smooth down there, like Ken dolls.”

And that is what The Beatles were very often about.

Currently I am reading ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ and that gives a sketchy celebration of The Beatles with their pants down, the silly, so stupid, pettiness and clashing ego’s, businesswise so stupid.

Artistically the movie was a failure, as was Magical Mystery Tour… let’s hope Lewisohn will get to the bottom of this failure to produce high class art… why did they go ahead while it may have been so badly timed and even worse produced.

There is a lot in the vaults. If “Don’t dig no Pakistani’s” is the apparently birth of ‘Get Back’… it really shows the way Paul creates his music… musically some rock music, words en melody pop up in his head and then he changes, takes away the controversial first, and changes, creates a third-person story, cause he is unwilling or unable to write about himself, though accasionally he does, etc. Would be nice…

The ‘Commonwealth’-atmosphere pictures the Enoch Powell days rather well. It is almost painful how universal and not restricted to time and place that disgraceful behavior and emotion appears to be, as it is happening all over Europe again.

Apple is right not to rerelease such a bad product again. But if all the recorded movie and sound material is still there, they should be able to come up with something…

I haven’t seen Let It Be in a million years. Where is it available? On the web?

Pam, that’s why I was surprised to see it. I suspect it was one of those VHS-to-DVD transfers.

I’m sure it’s torrentable somewhere on line–but for the life of me, I can’t figure that stuff out.

I think the Beatles’ breakup is something I’d rather read about than see, frankly. The scenes painted in “You Never Give Me Your Money” are painful enough: I don’t want to watch them being enacted, not even with good editing and commentary. I can understand why others wouldn’t necessarily feel that way, and I’m not arguing that no one should try to do what you’re suggesting with the footage, Michael. I’m just saying that I won’t be in the audience if someone does.

I remember seeing a multi-record set of the “Get Back” sessions at Reckless Records a few years ago: I believe it was 10 or 12 discs. My reaction was “Why on earth would anyone want to sit down and listen to all that?” My copy of the “Black Album” is more than enough for me, thanks.

How I wish we had film of the Beatles recording “Rubber Soul” or “Revolver.” Now that would be edifying.

Nancy, I think I’m with you, honestly–but if one was setting out to do what LIB purports to do, that’s how one could do it. And perhaps still do it, with unfettered access.

And I guess that’s my most frequent thought when watching LIB–how I wish they’d done this with Pepper, Revolver, Rubber Soul, anything BUT LIB.

@Nancy I admit I wouldn’t wanna see The Beatles infighting or break up, yet it helps to bring eradicate the group pressure to admire the four lads as much as their art. Why would I wanna believe the public image of the artist, which is a lie anyway, even when it is doctored by Derek Taylor. Whenever something new about the artist comes out I have to reconsider my perception of the artist and most of the time the impression and appreciation of the art fluctuates accordingly. I don’t want the truth, I want the art.

I want to appreciate the art, I want to disappear into the music, the emotions, thoughts and feelings the music and the words evoke…

The movie ‘Let it Be’ is boring, but on the bootlegs i can hear Lennon perform brilliantly ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ and really appreciate it. It shows how Lennon was always on top of it, even when he provided only guide vocals to the musicians.

I wish their were recordings of the composing process or the recording process of anyone song, and what they would say to each other… I have seen Dutch painter Herman Brood creating his art, amazing experience. I hope Apple has something of that in the vaults.

Rob, I guess it depends on how much pressure you see to admire the Beatles as people. I see them as very far from perfect, but that’s true of every mortal one of us. I don’t think we ever get “the truth” about any public figure completely — and how far the image of a particular public figure is a “lie” is a thorny question.

I also think it’s a mistake to base too much of one’s appreciation of art on one’s perception of how laudable the artist is as an individual. A lot of great art has been made by less than admirable people, and a lot of mediocre-to-terrible art has been made by some quite admirable ones. A melancholy reality, but there it is.

Interesting fact: Orson Welles is the biological father of LIB director Sir Michael Edward Lindsay-Hogg, 5th Baronet.

In my opinion, Michael Lindsay-Hogg was a poor choice to direct LIB. He had previously done only promotional video/film clips for The Beatles. The band should have hired the Maysles brothers, who did a magnificent job documenting The Beatles’ first visit to America in 1964 and were perfectly suited to this type of project.

Agree, @JR. I only alluded to this in the post, but much of what’s wrong with LIB is that it’s much too controlled by the subjects. Which is exactly what J/P/G/R wanted. The four of them were existentially unsure, and reacted to that in characteristic ways: Paul by micromanaging, John by withdrawing into another project (Yoko), George by being passive-yet-critical, and Ringo by being accommodating.

The Maysles would’ve been the perfect people for LIB.

“If “Don’t dig no Pakistani’s” is the apparently birth of ‘Get Back’… it really shows the way Paul creates his music… musically some rock music, words en melody pop up in his head and then he changes, takes away the controversial first, and changes, creates a third-person story, cause he is unwilling or unable to write about himself, though accasionally he does.”

That seems both unfair and inaccurate. Yes, Get Back started out as a satire — criticizing the racism in Britain at the time (and I suppose continuing today) against Pakistanis. He and John worked on the song as a satire and then, consciously, abandoned that approach because they feared people wouldn’t “get it.” They would think the Beatles were siding with the racists. And Paul and John were right, as, all these years later, I’ve seen people actually take those original lyrics and use them as some sort of example of the band’s racism. They STILL don’t get that it was satire.

And Paul repeatedly writes about himself in his lyrics (tho he doesn’t always admit the song is about him). I can think of many, many examples from the Beatles songs through to his music today. In fact, he’s been increasingly personal in the past 15 years. On the other hand, there’s nothing wrong with being a storyteller. John’s confessional approach is only one approach to song writing. And it’s not the best approach. It’s just one of many.

As for Let it Be, I think you’re right Michael. The movie is badly cut and a missed opportunity. But however depressing people find the beginning, I find the rooftop concert at the end to be joyous and uplifting. It shows what they could do when they got out there and just played.

@Drew you find my sketchy description of Paul’s way of composing ‘both unfair and inaccurate’. I might be inaccurate, however in the context of a review of all the material available for the ‘Let It Be’ movie I stated that some of the material allowed for a fascinating insight in the way a compisition occurs and grows. Thanks for your addition. i wonder what the source of your information is.

Unfair it is definitely not. Not being able or willing to write in the first person, about himself is something Paul acknowledges in various sources. There is nothing unfair about such a thing. It is very much like Paul Simon who somewhere in his late career found out he could write less perrsonally and make his compositional more abstract. And I am not convinced that writing in the first person about oneself is more valuable, more artistic more authentic than any other way of writing, creating ‘song’.

The other aspect of unfair you seem to include is that supposedly John and Paul understood they couldn’t be openly politiical. The Revolution Saga is probably The Beatles’ most openly political piece of art, for many outsiders. Acknowledging Paul’s and Brian’s, and why not anyone of the others, support of refraining from the political, is to me, not a negative thing. It just is, nothing wrong with that. It made them famous, it allowed their music access to many more minds than if they would have made their musical output more often openly political.

So much for unfairness. In this context it might be interesting to check out the interview with Blur’s Damon Albarn. http://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/apr/27/damon-albarn-interview-pop-showbiz-beatles-dylan-heroin

Rob, I do think your original description of Paul creating a song and “then he changes, takes away the controversial first, and changes, creates a third-person story, cause he is unwilling or unable to write about himself” sounded negative — maybe more negative than you intended. Part of the problem here is seeming to take “Get Back” as typical of how Paul works.

Both John and Paul write first-person songs and third-person songs, though John tends to write more in first person and Paul more in third. To take two examples from “Revolver,” “Nowhere Man” is a great third-person John song, and “Here, There, and Everywhere” is a great first-person Paul song. It’s fair to say that John more often offers up his emotions directly, which to me has its good and its bad points.

Nancy, as you know Lennon often backtracked on his songs, recasting seemingly third-person ones as first-person ones. “Nowhere Man” was about himself, sitting in Weybridge. Certainly that’s how Paul heard it: “That was John after a night out, with dawn coming up. I think at that point, he was a bit…wondering where he was going, and to be truthful so was I. I was starting to worry about him.”

Lennon’s gift and curse was that he could never really relate to anybody else. He realized this, as evinced by this comment he made in 1980: “You hear lots of McCartney-influenced songs on the radio now. These stories about boring people doing boring things – being postmen and secretaries and writing home. I’m not interested in writing third-party songs. I like to write about me, ‘cuz I know me.”

Is this earlier in the thread? If so, apologies.

Michael, I believe that long ago, on the Dullblog .blogspot site, you wrote that when Lennon wrote about himself, you often felt he was telling a story, and that when McCartney wrote a story song, you often felt that he was revealing something about himself. A sentiment I heartily second.

“Boring people doing boring things” — that’s sad.

Well, every once in 100 comments I hit the mark, @Nancy. 🙂

And I agree: John’s disdain for things he considered to be “common” demonstrates a fundamental immaturity in the man. The older he got, the more snobbish he seemed to become, and the less interesting he became as an artist. He was slowly more and more hemmed in by a sense of “propriety”–in his case, what was proper for a genius rocker/poet–but that’s as silly and small as Mimi wanting Paul to go ’round to the back.

It’s ironic that John Lennon himself seemed to be forgetting what made Beatlemania so explosive (and culturally important)–its dismantling of “propriety” in favor of honest self-expression, connection across boundaries, and simple human joy.

@Nancy… Maybe indeed unintended, but Paul is a composer a musician among the best and quite surely never stops composing. So there are a thousand bits and pieces ready to use and develop. My hunch is ‘Scrambled eggs’ is a fine example as ‘Get Back’ is, and probably the recent ‘Cut Me Some Slack’ as well, or take a lot of the raw stuff on ‘Electric Arguments’… Those are the not so refined songs, where as Yesterday, Hey Jude, Let It Be are skilled polished diamonds. It would be nice to have this composing and music creation proces of any of The Beatles documented in vision and sounds. Stick to the details etc.

I do have the sources to link to or to refer to right here and now, to show you how Paul acknowledge this ‘storytelling’ himself, and he prefers that over first person stuff. Yet there is first person stuff, or stuff like ‘Dear Friend’ and ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’. And then there is John Lennon who writes venom about Klein on ‘Walls and Bridges’ and then later claims it is about himself. And there he is spot on, a man of his time, any published art or any exprssion fot that matter about anything reveals something about the creator or expressor. You wouldn’t here that from Paul…

Again it is more a matter of fact thing I wrote. Maybe as fan I was pushed by journalist and group pressure, as I mentioned in another post/reaction, to see as little poppy in the art of The Beatles as the best quality of music with highly conscious words that guide us in life… Well I am way oast that point in my life now… And can appreciate Get Back as much as ‘No pakistani’s’. I think part of our conversation happens because this group pressure is still alive. That is why I like George Melly’s ‘Revolt into Style’ so much.

“The other aspect of unfair you seem to include is that supposedly John and Paul understood they couldn’t be openly politiical. The Revolution Saga is probably The Beatles’ most openly political piece of art, for many outsiders.” But Revolution doesn’t take a radical stance. For an “openly political” song, it’s really not all that risky of a song, lyrically. The song is all about advising caution: Don’t just tear down the system, have a plan/idea for what to replace it with. It’s also advising against destruction (even with John’s in/out waffling). But are either of those positions truly radical? How is “it’s going to be all right” a departure for the Beatles when that lyric is more in keeping with their message all along — a message that was about love, community, resolving problems together, working things out.

The Pakistanis lyric would have been different for the Beatles because it would have been an indictment of British racism — now THAT would have been truly political and radical for the Beatles. It would have risked outrage by the British press/establishment, much like Paul actually did risk outrage some years later with Give Ireland Back to the Irish. Part of me wishes the Beatles had released Get Back as a satire. Yet, as I said, I can see why John and Paul abandoned those original lyrics to Get Back. Too many people would have missed the point.

Yes Paul prefers to be a storyteller — and has been criticized for decades for that. Reviewers STILL review his recent albums and criticize him for not being more revealing, more confessional — as if that’s the “best” way for a songwriter to be. But it ain’t. It’s only one way for a songwriter to be. Yet time and again, John gets this goldstar for being “confessional” and Paul gets slammed for being too guarded when it seems to me, John was just more direct, more obvious in his lyrical confessions and Paul is less direct, more poetic in his lyrical confessions. John hits you over the head with is emotions, Paul asks you to think a bit about what he’s really saying because there’s hidden meaning here. Both approaches have merit. Paul IS confessional in his lyrics — in his own way — and some critics/fans refuse to see it. Ram, for example, is filled with angry, paranoid, depressed, sad, betrayed thoughts of Paul’s, and yet critics at the time of its release refused to see any of that, and some of them still do. Some of them STILL dismiss the lyrics on Ram as fluff or nonsense. I think the recent Pitchfork review of Ram was the first major review to understand the anger Paul is expressing on Ram, and to take the lyrics seriously. All you have to do is pay attention to see Paul’s personal emotions spilling out all over Ram. But people hear what they want to hear, and see what they want to see. They want to see John as the honest, confessional one so they ignore all the ways in which he dodged the truth in his lyrics. They want to see Paul as the sugary, superficial pop-py one so they ignore all the ways in which Paul revealed himself in his lyrics. They see depth where they want to see depth.

I actually found Rob’s very brief and to the core description of Pauls songwriting process about as accurate and concise as any I’ve ever read. Hey, you won’t find any bigger Paul fan than me (well, mayb Drew – but I’m beyond convinced by now that Drew is either one of Paul’s daughters or some kind of agent/PR for MPL ) and I see zero negative connotation in Rob’s description. The negative feelings come from perceived slights and the insecurity of Paul’s fans as to his songwriting prowess, which should be beyond doubt by now; the man is a genius and genius isn’t strong enough but there is no better word.

I’m prob late to this but there’s my 2¢

Craig, I read Rob’s description as somewhat negative in the same way I would read a description of Lennon’s songwriting as negative if it said something like this: “John focuses on himself and name-checks people because he is unable or unwilling to write about anyone else.”

There’s truth in that statement, and Lennon admitted as much. What bothers me is the way such a statement takes what makes Lennon’s songwriting powerful–its confessional sincereity– and presents it as a weakness.

I will plead guilty to bristling when I think people are criticizing McCartney’s songwriting unfairly, partly because that really was the critical line for so long (see Christgau, Landau, Norman, et. al.). And as that recent New Yorker piece by Ben Greenman about McCartney’s “generic genius” showed, this view is definitely not dead.

Per request from MG, here is my LIB riff from another post:

Michael, be prepared to wait a long time and I mean LONG time for someone to come on here and defend LIB. I can remember when I was just starting to get really into the beatles in high school and I came across a LIB VHS in my uncles basement while checking out his old records and I was super excited. You mean the beatles made a movie that’s not black and white that doesn’t take place on a bus or a beach or in Pepperland but was just them playing some of their later songs while looking awesome? is what I said to myself as I looked at the cover and read the back. This is before I knew anything. I was excited. Afterwards I was crestfallen. That movie can suck the joy and life out of anyone. Instead of blasting metal rock at Gitmo to detainees they should just force them to watch LIB on a loop and I’ve no doubt prisoners would spill their knowledge after 1 viewing.

Now, the concert at the end has some of my all time favorite moments in the groups repertoire. This gets very nerdy beatley but there’s a point during 909 when John and Paul catch eyes for the briefest of seconds and both smile at each other in a very knowing and understanding way. This was a song they had been playing together since they were 17 and that look to me says that after all those years not only did they still enjoy playing together (sometimes) but that they finally nailed that song down and the satisfaction was evident. There is joy on that rooftop if you look for it.

Wow I just went on such a random tangent that I think I ended up disproving my initial theory and defended LIB!

Reply

Thanks, Craig, for being so respectful of someone else’s opinion that you accuse them of being a PR flack. Nice. And no, I don’t work for Paul. I just think this idea that he doesn’t reveal himself in his lyrics is garbage.

Hey, I don’t work for the Harrison Estate either and NONETHELESS think that Extra Texture is a great album! 🙂 OK, that was my last contribution on that topic.

A thoughtful essay about the Paul/John collaboration:

http://www.theatlantic.com/features/archive/2014/06/the-power-of-two/372289/

[…] Some part of this late-60s demolition was simply fashion, grist for the mill; but at its best, there was a well thought out, humane philosophy behind it, a belief that myths get people killed. So, what did the Beatles wish to say to their fans, circa 1969? Here is what we really are, here is what it really is. Don’t be fooled (perhaps like we were). I discuss the unremittingly dour Let It Be, and its possibilities, at some length here. […]

[…] I do, however, I want to link to a Dullblog post I wrote in 2014, “Let It Be: A Missed Opportunity.” Re-reading it today I think it’s quite prescient. I am not saying that Peter Jackson […]