- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

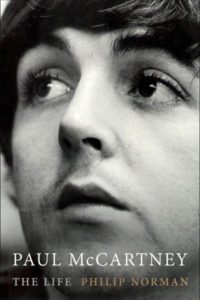

Paul, looking over his shoulder

Adam Gopnik has contributed a peculiar review of Philip Norman’s new bio, Paul McCartney: The Life. The TL;DR is “A reader familiar with the past twenty years of Beatles biography will have a pretty hard time finding a single new fact or revelation within [Norman’s biography].”

Pretty damning, right? Apparently not; Gopnik hastens to add that we shouldn’t blame Norman. “After Lewisohn; after Barry Miles’s strange Many Years from Now, a semi-official biography; after Albert Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon and the Beatles Anthology series, there just isn’t much left to say. Even if there were something left to say about McCartney’s life in the forty-six-year period since the Beatles’ breakup, the crucial seven years that make the rest matter are by now almost too well documented.”

Suddenly we’re not talking about Norman’s book, or even Paul McCartney, but Gopnik’s fatigue with the subject of John, Paul, George, and Ringo. After eight plus years of Dullblog, I feel ya, Adam — but there’s something weird about taking the time to write this review, much less deciding to publish it, if your core belief is “Meh, too much Beatles.” It’s difficult for me to have much of a reaction towards Gopnik’s piece, though, because there’s so little there to react to. The Beatles have been studied a lot? Why yes, they sure have. Why, then, did Norman write the book? Why did his publisher commission it? Good idea, or bad idea? Why are people still so fascinated? What does this Beatle-oversupply say about music, pop culture, modern media? Anything? And should people interested in Paul McCartney buy the book?

This latest generation at The New Yorker goes weirdly limp when confronted with the Beatles, and I have a guess why. Thanks to editors like Tina Brown, contemporary American magazines now live in a weird binary space, intellectually speaking; they long to either set the conventional wisdom on a topic, or overturn it. Everything else seems like small potatoes.

The conventional wisdom is that the Beatles are the ne plus ultra of modern pop, but there’s no juice in agreeing. It’s so culturally unassailable that no New Yorker writer can disagree without risk to the gravitas of the institution; The New Yorker isn’t some dude writing on Pitchfork. So what’s to say?

Even more than authority, contemporary media writers long for the Slate-like contrarian take. The only time Gopnik’s mind seems to engage is when talking about the recent contrarian biography of Allan Klein. This leads him to some very bizarre statements: “The problem is not that [Klein] was a thief [was he? Opinion, Adam?–MG] but that he worked in a business where thieving, of one kind or another, was the business.” Except that there’s a massive counterexample standing right there, in the person of Brian Epstein. Would the Beatles have ever happened, had Epstein been a Klein-like sharpie? Now that’s an essay worth writing — not only for the personalities involved, but for the larger questions of business ethics in our new Gilded Age. Perhaps what makes people more willing to excuse Klein’s chicanery now than in, say, 1975 or 1985, is the general deterioration of business ethics that is a necessary precondition for the 1% leaving the rest of us behind.

Gopnik consistently overplays his hand on this topic, saying for example, “In fairness to Klein, it should be said that few people imagined that the pop music of the period would be remembered eighteen months afterward, much less that it would still be hugely valuable half a century later.” In fairness to reality, that’s simply not true. In 1971, everyone from Sir Lew Grade to Jann Wenner to the stoned residents of dormitories the world over all believed that Beatles music was a valuable cultural commodity. And that’s the reason Klein couldn’t swindle Paul McCartney like he swindled Bobby Vinton. The reason a British court sent the Beatles into receivership wasn’t that the Eastmans played dirty or got lucky — it was because, even in 1971, the Beatles were considered to be one of Britain’s cultural crown jewels, worthy of being protected. And the court saw that Allen Klein was no protector, he was a gonif.

The unfortunate thing is that Gopnik’s clearly a fan — only a Beatle person would point out the perverse illogic of Norman’s earlier book being called Shout! (I remember spending a teenage afternoon trying to figure out whether the Beatles actually recorded the Isley Brothers’ song; surely their biography wouldn’t have been titled that if they hadn’t?) There’s something good, even great in him about the Beatles, but this ain’t it, and the central question remains unanswered: should fans plunk down their hard-earned for Norman’s book, or not?

I don’t really have an opinion on the review, but the thing about the Beatles never recording Shout is untrue. They have recorded it, and it sounds quite fun, though I understand why it was never on an LP.

Re: this book… it appears to be more fair to Pau, but I’m still skeptical.

Chantal, where did they do it? BBC?

It was recorded for a television show. It’s on Anthology 1. What I like most about it, aside from the fun they obviously had doing it, is that they all sing lead.

http://www.beatlesbible.com/songs/shout/

The book that has yet to be written (and I’m assuming here that Norman’s book on McCartney isn’t one of them) is one which accurately and carefully (and correctly) examines the Lennon/McCartney relationship. Anyone who says that there’s nothing more to learn shouldn’t really be writing a book review. And yes, Adam, I mean you.

The problem is not too much Beatles. It’s too much Adam Gopnik. Stick to art history, ace.

@Sir, what Gopnik do you like? What should I read, if I wanted to? The guy writes a good essay, it’s just that TNY seems to throw him at everything, including topics like this one where his level of interest is so low, he’s forced to end with anecdotes from his spouse.

As an historian by training/education, I don’t necessarily agree that any subject could be covered too much. I find Gopnik’s assertion that there’s “nothing left to say” lazy, especially as he dismisses anything about Paul’s life beyond the Beatles years. Any subject can be covered too much in the *same way*, and that’s the problem with Norman’s book. I read the excerpts in the Daily Mail, and you could slap Howard Sounes’ or Peter Carlin’s name on them (to name two recent Paul biographers) and no one would know the difference. It’s not just the same story, it’s the same story told in the same way, often using the same sources, down to the same previously published quotes being used over and over again.

Until recently, Alexander Hamilton was considered one of the lesser and less popular Founding Fathers. Then Ron Chernow and Lin-Manuel Miranda came along and looked at his story in a new way, with fresh eyes, and the rest is history. Thomas Jefferson is another example. You can’t just treat history and biography as passive entities, you have to be passionate and proactive if you want to say something new.

As a McCartney fan, I can think of plenty of fresh perspectives and issues that have never been touched in Paul biographies:

-The influence of Paul’s parents, beyond “his dad was a musician.” How did their differing personalities shape Paul’s? How did their somewhat unconventional gender roles for the time shape his views? Also, how did Liverpool’s singular culture – the immigrant influence, the working class outlook, the leftist political views – influence his worldview?

-What’s Paul’s relationship been like with his brother? After acknowledgement that the McCartney brothers were best friends and constant companions in childhood, Mike disappears from any telling of Paul’s life story, despite still being a presence at key moments of Paul’s life. How did their relationship evolve? What has it been like in adulthood?

-What about Paul’s relationship with John Eastman? By many accounts, John has been not only one of Paul’s closest friends for decades, but also his closest adviser. How did they evolve from merely brothers-in-law to that relationship? Just what *has* John Eastman’s influence been on Paul’s business and legal decisions, both the triumphs and failures?

-Paul’s daughters Stella and Mary seem to have a huge influence on his life in their adulthood. Mary in particular has said interesting things as well about Paul’s influence on her work as a photographer. It seems to me a bit unusual for a rock star’s daughters to take such a matriarchal role – so is it? How exactly do they work with their dad? How have they kind of “taken charge” and spearheaded the McCartney clan after Linda’s death?

-Why is there not more exploration of Paul’s various collaborations? Has *any* star of Paul’s generation collaborated with as many artists of various ages and genres Paul has? Why is he the sole Beatle to collaborate significantly with African-American artists?

Until recently, Alexander Hamilton was considered one of the lesser and less popular Founding Fathers. Then Ron Chernow and Lin-Manuel Miranda came along and looked at his story in a new way, with fresh eyes, and the rest is history.

This is exactly right. In fact, Hamilton was often portrayed in a negative light, as opposed to Thomas Jefferson, the charismatic genius. Sound familiar? 🙂

See, right here is an example of just how exciting, deep and compelling an actual history of Paul McCartney could be. I really really REALLY want to see those subjects explored. So much is written about the warmcaringboisterousmaternaldrunkenviolent-ness of Liverpool family culture, and much more is written about how much that was missing from Lennon’s life – surely Paul’s family relationships are absolutely key, surely they need real in-depth exploration? Lewisohn does such a good job at giving the context and telling some great stories, but he left me wanting to really understand so much more about how all these things fit together.

Because, of course, his relationship with his parents and his brother will have influenced how he developed close relationships with others, or not, including John Eastman.

Paul’s life requires much more digging than John’s, and that’s partly why so little true excavation has been carried out. John made it easier to look into what made him tick. Paul doesn’t want you to know – he either thinks it’s not important or he thinks you have no right to know; what information he gives is given because he needs to give it, not because he’s choosing to reveal his life to you. You could maybe make the argument that he forces you to work hard to understand him, but it’s more likely that when he reveals his emotions and history in his music, he’s doing so for himself, not for us.

He has allowed the curtains to be drawn on the depth of his familial and personal relationships, but surely that should be an absolute killer draw for a serious biographer. What a fantastic challenge! How did that guy turn into this guy, doing those things with these people – and I don’t just mean The Beatles, I mean the rest of what you said, Ruth – the collaborations, the willingness to put himself out there.

If I’m honest, I find Paul so much more interesting than John – because we can all write John’s story. Abandoned kid, lives in pain, expresses pain through art, smashes up the best things in his life, dies as an indirect result of the type of person he was. It’s almost exactly what you’d expect the story to be.

But Paul? That’s a real challenge. And such an interesting story. And again, so much not what you’d expect it to be. Even now, I find it utterly fantastic that Paul was the hip Beatle in the mid-late 1960s, having been brought up with the background noise of “Paul is the saccharine one and John is the real artist”. Paul as the arty intellectual – that’s not how the story is supposed to go. And even though I’m not a big fan of his later work, you’ve got to love just how much he was and still is willing to put himself out there, working with such an odd bunch of people.

It’s a story I would so love to read.

Actually, I wish someone would write an in-depth study of the relationships between all the Beatles. Listening to the pretty poor “Something about the Beatles” podcast recently – two men making really bad jokes about women, attacking Yoko for being a “bad feminist” cos she manipulated other women, and so on – I heard what could’ve been a great episode about the relationship between George and Ringo.

And yet as soon as the discussion turned to their actual physical closeness, with tales of them cuddling up in bed together even once they were famous, the presenters expressed disgust at the very idea of two men doing that (I’m not joking – these are the same two people who, on mentioning Epstein’s family home being on “Queen’s Drive”, said “I’m not saying anything *snigger*”). And then they stuck to rehashing exactly the same headline stories that we’ve heard for years.

There are so many good stories to be told about all four of them. I mean, think about that – two guys from the most completely working class city on earth, brought up under extremely strict emotional conditions, spend their nights cuddling each other in bed even once they’re successful enough not to need to be in the same room, let alone the same bed. There’s so much in that story, clearly so much more to be said about the bond between all of them, but we’re still stuck, stuck with this review, stuck with these books, stuck not being able to look at the actual relationships and how they were at the heart of what made so much magic happen in the studio. And that’s the point in the end. If you want to understand Revolver, don’t you need to understand how close George and Ringo were?

I want to hear those stories, but they probably won’t be written til after I’m dead. Right now, the cultural leadership of the west is intent on not allowing us to examine something so amazing. They won’t allow Paul to be anything more than a soppy songwriter, second to John. It’s heartbreaking in a way.

“Paul doesn’t want you to know – he either thinks it’s not important or he thinks you have no right to know; what information he gives is given because he needs to give it, not because he’s choosing to reveal his life to you. You could maybe make the argument that he forces you to work hard to understand him, but it’s more likely that when he reveals his emotions and history in his music, he’s doing so for himself, not for us.”

.

YES. You put this really well, Evilpants.

.

As I’ve said here before, while part of me also wants to read the kind of in-depth work on McCartney that Ruth so eloquently points out could be possible in the right hands, part of me is rooting for him to succeed in keeping those curtains closed — at least as long as he’s alive. I’m sure that one reason I tend to identify with McCartney is that I also guard my privacy. The prospect of people digging through my past and interviewing everyone I’ve ever known would fill me with horror. So I feel odd about reading bios of living people where that kind of digging has been done, even if that person has chosen to live a public life.

Chiming in here with my usual “this is how books are written” perspective — which is always received SO WELL 🙂 — the kind of biography that you guys are asking for would be fascinating, and definitely is the kind of book that a subject that McCartney demands. But there are a couple of practical problems.

The first and biggest is access. If a biographer cannot get access to subjects, he/she has to surmise. And surmising leads to the second problem, which is legal. Paul McCartney is a publishing lawyer’s nightmare — he’s fabulously wealthy, lawyered up like crazy, and immensely beloved.

Paul requires a psycho-biography something like “The Life and Death of Peter Sellers” — though, I hope, much happier than that book. But he will not get it, for the nicest of reasons: he’s lived too long!

Chiming in here with my usual “this is how books are written” perspective — which is always received SO WELL

Party pooper. 😉 Do you think the kind of book we’re talking about could be written posthumously?

Yes, I do. But I think it would be difficult even then, because as Paul ages, many of the sources die and/or their memories fade. And the money and interest necessary for the digging fades, too. The Lives of John Lennon exists because John Lennon died when he did, as he did; if he’d died at 70, the majority of that information would have been lost (for better and worse). A book would’ve been written, but not that one. Probably something like Coleman, to sop up the fan dough, and no more. We only know so much about John because he died when he did, how he did.

The book that you guys seem to be describing is, to me, a sympathetic, yet highly forensic psychobiography. Not just what Paul McCartney did, but who he was, and how he became that.

Surprisingly perhaps, the closest thing you have to that within the Beatle canon is Goldman; everything else seems to foreground the public image of the band, which is just a public image. Goldman’s animus helped him avoid that trap — while throwing him into a million others. The only other biography I know of that really digs at its outwardly sunny subject, like you would need to with Paul, is The Life and Death of Peter Sellers.

Why so dark? As much as this pains fans to recognize, one does not acquire the drive of a McCartney without some kind of primal injury; one does not recreate the world, song-by-song, without some deep unquenchable pain-driven need. It’s too hard. It’s too boring. We live in a Golden Age of TV.

Do you really want to know why Paul craves to fill stadiums at 73? I’m not sure I do. I think our choices are, have the fundamentally sunny Paul that we have now, but know rather little about his internal life; or trade that persona in for a darker one, with more knowledge. It’s like the John F. Kennedy we knew in 1965, or the one we know today; I personally like knowing more, because I’m so empathetic as a reader, but most Kennedy admirers are sorry they know about the philandering and the gonorrhea and the cocaine.

I don’t think we’d find out anything that would gainsay Paul’s musical brilliance — but I do think our portrait of him as a person would become a lot, lot darker. And he might not want that — why would he? How does it benefit him? The peculiar thing about Lennon isn’t his darkness, which is standard in showbiz, but how he seemed compelled to not only admit to it, but direct the audience to it.

Here’s perhaps why: Lennon knew from his own life and those of the people he’d met that extraordinary people live extraordinary lives. Fans want them to be extraordinary in one way, but “just plain folks” in every other one. It doesn’t work like that, so many fans choose to remain childlike in their appraisal of their beloved. Others actively deny that which they find shocking or distasteful. Others fall out of love. All of these are fundamentally narcissistic reactions; if Paul (or anyone like him) is monstrous, it’s us who made him so — so I say, let the truth be known.

I’m not sure if you’re suggesting this MG, but I wanted to add that our interior can be complex, delicate, fragile, and closely protected without being “dark” in any seriously nefarious sense.

The thumbs-aloft, smiling Macca is a caricature, and one wonders why Paul insists upon presenting such a one-dimensional persona until you realize that, as you pointed out, it’s a protective measure. What the persona is protecting would be a fascinating subject of discussion.

What I’m suggesting is the Jungian idea of the “shadow.”

Given that Paul is a fiercely creative person with a squeaky-clean public persona, it is highly likely that his shadow is significant. Whether its expressions have been “nefarious” or not will have to wait for the tell-all bio which I suspect will never come (see reasons upthread).

In retrospect, the revelations of The Lives of John Lennon were completely predictable; there was an almost mathematical reflection of John Lennon’s public persona (mostly clean, devoted househusband and father, interested in world peace) and his private flaws (drug addicted brothel patron, uninterested in Sean, and physically violent). And the reaction of the public was equally predictable. Similarly the private flaws of George — heavy drug use; philandering; a bit of the Scrooge McDuck — are the exact opposite of his assiduously maintained, and doubtless sincere, commitment to meditation and Hindu spirituality.

Is the private Paul as truly excessive as the private John was? Or is he closer to the more typical celebrity private George? Who can say? I suspect Paul hasn’t quite reached John’s levels of acting-out — the public John was really running for sainthood in a way that Paul usually does not — but we must entertain the possibility.

And this goes doubly so if we’re highly enamored of Paul, as many Dullblog newcomers are. One’s favorite Beatle is a projection of one’s own needs and desires, goals and injuries — not of the reality of that person. In my own experience, when I cling to a belief that a celebrity is “good,” I am using an image of that celebrity for my own psychological needs. The reality of that person is — must be — different, because people as they exist are different than our conceptions of them.

In any case, in our contemporary world of omnipresent PR, it is always a good idea to hold opinions on celebrities — negative and positive — pretty lightly.

the presenters expressed disgust at the very idea of two men doing that (I’m not joking – these are the same two people who, on mentioning Epstein’s family home being on “Queen’s Drive”, said “I’m not saying anything *snigger*”).

THIS.

I am SO SICK of this bullshit. GO AWAY, people like this. Just die already.

I have tried to listen to that podcast several times, and it did not grab me. On the other hand, I randomly listened to something called “Zappacast,” which is what a Hey Dullblog podcast could be like.

spend their nights cuddling each other in bed even once they’re successful enough not to need to be in the same room, let alone the same bed

I wonder if their need for so much physical closeness had a lot to do with their being the only people at the center of all the madness. They have said many times they were the only ones who understood what they were going through because they were the only ones going through it, and how sorry they felt for Elvis who had to go through it alone. I hate to use Paul’s army buddy analogy but their need to cuddle together and hide in the bathroom together reminds me of scared soldiers huddled together in the trenches while everything around them is in chaos.

“I wonder if their need for so much physical closeness had a lot to do with their being the only people at the center of all the madness.”

I think this is right on the money.

“the crucial seven years that make the rest matter are by now almost too well documented.”

And there’s the crux of it. There are people who firmly believe that Paul McCartney’s only relevance to history or popular culture is as John Lennon’s sidekick, and have no compunction about stating this publicly. If you believe this, how in the world are you going to write a book that is in any way insightful or interesting? Why bother? If you can’t contribute anything new to the conversation, STFU. I don’t need to hear the same stale opinion for the millionth time. Respectfully (I never read SHOUT! so can’t comment on its alleged brilliance), I think Norman is a giant hack.

This is what I mean when I say people either “get” McCartney or they don’t. This man is doing world tours, filling football stadiums at 73! And then getting on a plane to go take his 10 (?) year old daughter to school. The longevity of his career and the endurance of his creativity is staggering (whether it’s your personal cup of tea or not). If you don’t find that fascinating, you must think humanity has nothing left to learn about geriatrics, the creative process, parenthood, human survival and performing arts. IMO, McCartney’s brain should be put in a jar. But if you stubbornly believe that he’s just a remnant of a great band…. OK. But why write a book to that effect?

Frankly, I’m just ready to toss the old Beatles-author brigade. These guys are amateurs. 😉

@Chelsea, it’s much more damning than that. They aren’t amateurs, that’s the problem. They’re professionals who believe that by being professionals they have the right to insist we share their disinterest. That there’s nothing to see here.

Shout! is lively and colorfully written. Like The Compleat Beatles, it was the first taste of the larger story that hadn’t been yet told. At this point, its impact is nil for any serious fan.

The only Beatles book I’ve put my hard-earned money down for is Tune In. Everything else I’ve checked out from the library; I should be getting Norman’s Paul bio as soon as the library releases it.

Even the issue that it holds almost no new information is fine; I will simply be fascinated to see the contrast between the varying versions and interpretations Norman has given over the years.

I have already discussed, in previous posts, why I believe Norman is writing this bio of Paul. I would argue that it has as much to do with Norman attempting to salvage his reputation as a Beatles authority, as it does with a new, profound reversal of his previous stance regarding McCartney as an artist or an individual.

The willingness of Gopnik to swallow Goodman’s version of Klein, simply because it offers a new way to tell a familiar story, is disappointing. I read Goodman’s work, and its littered with errors, unbalanced versions of events, and significant omissions, all in order to salvage Klein’s reputation. I agree with Goodman to an extent: Klein has been conveniently demonized, in part because its easier for fans to blame Klein than John, George, or Paul, and you have many authors which use retrospective evidence against him so that John, George and Ringo’s choice of him becomes virtually inexplicable. Goodman’s work pushes back against the caricaturization of Klein, and I’m supportive of that, but it only succeeds in doing so by committing serious methodological and interpretive errors. And that I can’t support.

@Ruth, your buying behavior is really interesting. If you are not buying these books, I wonder who is? I’m not buying them either, by the way.

I don’t think one has to work hard to explain why John, George and Ringo lined up under Klein, because nothing suggests that they were acting particularly rationally. I think John, deep in the throes of heroin addiction and egged on by a possessive new girlfriend, was acting to hurt Paul — think of it as another way of insisting they record “Cold Turkey.” There’s no mystery to any of that. And I think the other two were convinced by John’s simple logic. “Mick said he was OK; and do we want Paul’s father-in-law managing the group?”

Nothing about John, George, or Ringo’s subsequent careers suggest that they had/have much financial acumen. That’s OK; why should they? I think they were three marks for a very experienced con man. That reading actually fits a lot more closely with John and George’s subsequent careers (John’s legendary fecklessness in regards to money; George’s being massively swindled by Denis O’Brien) than Klein not being the bad actor that he’s been portrayed to be.

The part that jumped out at me was Gopnik’s assertion about partnership agreements not usually being dissolved when one party disagrees. (“As Goodman shows, the law and the facts were very strongly with Klein: a contractual four-way partnership can’t normally be sundered by one partner’s discontent.”) Obviously, that would have to do with the agreement in question; but more importantly, this wasn’t a simple agreement between four equal partners to run a bakery or something, with each party obliged to perform certain definable tasks. If Paul didn’t want to work with the other three to produce work represented by Klein, no agreement could make him do it, and that’s perhaps another reason why the High Court put it into receivership — if Paul was intransigent over Klein, and he was, there really was no way forward. The partnership existed in name only, and preserving it helped only Klein, who wasn’t a partner.

I agree that Klein was a bad actor, and an absolutely horrendous choice for manager, if your ultimate goal was to keep the band together. (Whether that was, of course, John’s ultimate goal is debatable). The issue I have is when writers use evidence that was unavailable to the players at the time to introduce and portray Klein in such a scheming, cackling, negative light that entrusting him with anything more than a five pound note becomes inexplicable. Specific example: if, as an author, you are introducing Klein into the narrative in January 1969, and you include a reference to later events, such as his later 1970’s imprisonment for tax evasion. John, George and Ringo knew Klein’s reputation — Ringo said in 1971 that one of the reasons he chose Klein was because Klein was a “hustler” and Ringo wanted someone “hustling for me” — but they didn’t and wouldn’t have known about that. Introducing Klein as a “hustler” is valid; introducing him as he enters the Beatles story as an ex-jailbird is retrospective.

I don’t remember whether its in Goodman or not, but the analysis of the partnership law I read explains that the 3-1 majority ruling being legal only applies so long as the majority does not become injurious or abusive the outnumbered party. That’s why John, George and Ringo’s signing contracts granting Klein’s increased commissions without notifying Paul was so crucial; it was clear evidence that his being outnumbered and outvoted was detrimental. And yes; the concept of legally forcing Paul to unwillingly contribute to a dead creative collective is beyond bizarre: what could they do; chain him to a chair in Abbey Road and not let him up until he wrote a melody or crafted a new bass line?

@Ruth, I think you could point to Paul’s letter re: “The Long and Winding Road” as further evidence of this “injurious and abusive” standard, and that is doubtless why Paul was instructed to write it. (If you can express yourself in a phone call, you only write a letter when you want a paper trail.)

And it also shows how woefully uninformed he is about his subject matter. Makes me want to send him a letter with a link to this blog. 🙂

Best line from the article is the one describing John and Paul’s meeting:

“scary, hyper-mature, and aggressive John meets sweet (though sexually precocious) Paul, and something happens.”

LOL.

Also, for anyone interested in the story of how the story of the Beatles has been told, there is a new book out that looks promising:

http://www.mcfarlandbooks.com/2016/04/newly-published-beatles-historians/

I’ll be reviewing that book in the upcoming weeks. Stay tuned. 🙂

I’ll be reviewing that book in the upcoming weeks. Stay tuned.

I’m looking forward to that Karen. I’ll be watching for it. Looks like a very interesting book but unfortunately even the Kindle version is 25 bucks. Until I can track down a library copy, maybe your review is the closest I’ll get to reading the actual book.

In the interests of full disclosure, Stew (and everyone else reading this) that new book is mine. “That’s right; I shot J.R.”

I *may* have mentioned here, a time or two, that I find the study of historiography, regardless of subject, compelling, and the deliberate obscuring of known evidence immensely frustrating (I once yelled “bull*#*#” in the middle of the Imperial War Museum when I saw an exhibit declaring that Winston Churchill was an avid, tireless supporter of the Invasion of France in World War II). And I find Beatles historiography as compelling and complex as the historiographies of subjects like Cleopatra, or African-American slavery in the ante-bellum South. (Now there’s a topic with some dramatically shifting narratives and interpretations, not to mention all kinds of bias). Because I was reflexively applying a historian’s methodology to Beatles historiography as a casual reader, I decided to make a study of it, and write an article, which mushroomed into a book.

It’s a historical analysis as well, using standards … blah blah blah; it’s all there in the book’s introduction, which you can read on Amazon, if you want to.

Thanks Ruth for the disclosure. 🙂

I received the publisher’s copy today for review, and am hugely looking forward to reading it. You can expect the review to appear on HD around the end of May.

Oh, I can’t wait! Read quickly Karen!

Ruth if your book is anything like your interesting comments here, and I expect it is, then I’m really looking forward to reading it.

Thanks, Linda. (Btw; I agree about the price being a mite hefty, but that wasn’t up to me).

I do want to stress that there is a crucial distinction between casual discussion here and the content of the book, however, and that’s the intended audience. I wrote it as a college textbook, not for Beatles fans but for history majors taking Historical Methods or Historiography and wanting to examine something more modern than WWI — which is fascinating, but, let’s face it, has been done to death. It assumes that the reader will have more familiarity with historical methods than they would the Beatles.

In parts its very academic and textbook-y, and certain sources were chosen primarily to illustrate a particular historical methods issue: For example, any historical methods textbook needs to include the standards used to evaluate a source’s credibility, so, in the 2nd chapter, there’s an analysis of George Martin’s overall credibility — both the reasons to believe and *not* believe his version of events and what reasons he might have for bias, etc.

Again, full disclosure: it’s a college historiography textbook, a phrase which puts lots of people to sleep. But if that still interests you, I’m glad.

Thanks, Linda. (Btw; I agree about the price being a mite hefty, but that wasn’t up to me).

You’re very welcome. I look forward to reading your comments…And yes I know that pricing is up to the individual publishers and is out of the author’s hands so I know you had nothing to do with their decision to force Amazon to charge the customer $25.00 for an ebook. The prices for ebooks are creeping up and I know that is purely the decision of publishers, not authors or online retailers.

the 2nd chapter, there’s an analysis of George Martin’s overall credibility — both the reasons to believe and *not* believe his version of events and what reasons he might have for bias, etc.

Sounds fascinating to me. I have put in a request for my local library to purchase this book. 🙂

I wish Gopnick had spent more time reviewing the book and less giving his (not especially well-informed, IMO) opinion about Klein and music royalties.

I look forward to seeing your review of the Norman bio, Karen, but I don’t think I’ll be reading the book myself. The only way to write a truly relevant bio of McCartney at this point would be to offer a new, balanced take on his whole career arc, and I don’t see Norman as being capable of doing that.

It also bugs me, as an editor, that Norman titles his bios with the definite article (THE life of Lennon, THE life of McCartney). A little humility wouldn’t go amiss, in such a crowded field — especially when Norman’s been hard on others for their perceived lack of it.

It also bugs me, as an editor, that Norman titles his bios with the definite article (THE life of Lennon, THE life of McCartney). A little humility wouldn’t go amiss

He strikes me as someone who doesn’t have much insight. He’s very obtuse.

It’s not the Norman bio I’m reviewing, Nancy, it’s Ruth’s new book.

Well, that’s another kettle of fish entirely. There’s a book I want to read, along with the review of it!

🙂

And I’m with you about Norman’s book–I would read a review, but I’m not prepared to buy it. I didn’t like Shout! and I didn’t like his bio of Lennon either. Maybe Gopnik’s review of Norman’s new book on McCartney is meh because the book is too. We’ll see I guess.

Anyone else find the cover shot an interesting choice? Paul, wide-eyed and pretty, looking off into space, innocent as a lamb? Compare that to these. Was the intent to show his beauty (which, granted, is easy to do, but still….)

I was wondering the same thing. Did Norman pick the photo design? Was he offered choices and given final say?

I wonder if the choice of a younger Paul was seen by the marketing department as being more attractive to book buyers. That readers would somehow be turned off by an old man on the cover?

If that’s their logic, I disagree. A “cute” 1964 photo makes it look like all the superficial books that flooded the market in the 1970s. A moody, heavily-shadowed portrait of a wrinkled old Paul would make it look more like a serious examination of his whole life, rather than a rush job about what Yoko called the “mopheads or whatever”…

I think the photo is from 1966, but even so, I agree we could ‘suffer’ elderly Paul all the same. The choice was probably because of the ‘eloquent’ eyes. (I wonder, is there a tear in his eye? It looks like a creased contact lense 🙂

The man had amazing eyes, that’s for sure.

@Sam, Norman would’ve been shown the cover, but all such decisions are exclusively the publisher’s. (I know this because I nearly walked away from a $50K deal because the proposed cover and packaging would’ve been catastrophic.)

I think the logic, such as there was any, went like this: “This book is for nostalgic old ladies who once screamed at Paul and will buy anything published about The Beatles.” Moptop is what they think they’re selling.

Geez, you’d think that the author would have the right to pick his/her own book cover.

I think you’re right, Mike–the cover choice was deliberately “pretty.”

Geez, you’d think that the author would have the right to pick his/her own book cover.

Or title. *cough*

You can’t even pick YOUR OWN TITLE? Dang!

Would make sense that the cover is about what is most likely to sell. Unfortunately, I think it also plays into the McCartney’s-years-with-the-Beatles-were-the-only-interesting-ones idea. His bio of Lennon didn’t have moptop John on the cover.

I love looking at pictures of beautiful young Paul McCartney, however…

That black and white photo of aged Paul, senior years, gray templed, face partly shadowed, lined, wrinkled, jowly even… lips…pursed, ever so slightly…eyes…looking directly back…at me…unflinching.

A hint, of annoyance captured for posterity. I know because the photographer said so. She didn’t want, smiling, jolly, thumbs up Paul. “What! no whimsy?” She said, he asked. “No! You always give that to all the photographers, all the time!” She said, she answered. That seemed to piss Paul off, momentarily, it flickered on his face, and she got it on film. “He hated me and I loved him for it!” Her words.

That face. That aged Paul face, I have studied it, and have come to love its gravitas, its power…its aged beauty. Its earned every line and wrinkle it has lived. Maybe that’s the artist in me, but now that photo is one of my favorites of a posed Paul, caught without his jolly mask.

His eyes made me flinch, fidget, and frankly…swoon!

Water Falls, GREAT explication of that black and white photo! I also love the way it echoes the cover of “With the Beatles” / “Meet the Beatles.”

I didn’t know that story, Water Falls, wow.

Guys, I wanted to find the name of the photographer, and the article with the story of the photographer, who took that fabulous photo of aged Paul McCartney that I discribed. I’ve been googling and searching early this morning and what I have discovered is that the photographer is Chris Floyd, based in London, known for taking pictures of famous people, celebrities etc. This photographer is very much male in gender, which calls into question who was this “she” I was discribing in comment. Frankly I don’t know, but I do remember reading the article about woman photographer, who was scheduled to have 15-30 minutes to take pictures with McCartney who was late, and didn’t have time to pose after the photog was kept waiting for like 2 hours, so they rescheduled and she was promised, like an hour to make up for the blown photo shoot.. At this rescheduled shoot, Paul kept giving her all his standard

smiley funny faces, thumbs up, whimsy shtick, frustrating her greatly, as her time was running out. That’s when she confronted him about it, got him pissed off, captured two or three unsmiling shots, before his mask returned. I thought that b/w picture shown above in Karen’s comment was it (it’s the one I remembered with the article) but now I know that it was taken by Chris Floyd, so maybe I remembered wrong. I’m embarrassed for the mistake, although I know I read the article, I’m 99% certain ‘that’ photo, along with another, where he is wearing that same outfit was used with the article I discribed. I just thought I’d better clear up any misconceptions I brought here and clean up the mess I made. So very sorry folks.:(

I was thinking that, Nancy. Norman’s bio of John had a 70’s shot. That also was interesting.

Interesting thing about that Lennon cover: that’s the LEAST iconic period of Lennon’s life. He’s not a Beatle, early- mid-or late. He’s not Lennon Remembers Lennon. He’s not househusband John. Or DF John.

I think it’s from the 1974-75 Walls and Bridges period, no?

I love this performance of “Shout” by the Beatles– one big reason being that they ALL have a turn on lead vocal. It IS fun!

Video link: https://youtu.be/k5h4T_kfBcg

I love Beatles’ covers. They rocked out “Shout”, IMO.

Mike: The first and biggest is access. If a biographer cannot get access to subjects, he/she has to surmise. And surmising leads to the second problem, which is legal. Paul McCartney is a publishing lawyer’s nightmare — he’s fabulously wealthy, lawyered up like crazy, and immensely beloved.

I’ve sort of accepted that I’m simply not going to see the sort of work that does Paul’s life, art and history justice. But, as a typical man (the sort of man who, when Tony Blair became leader of the UK Labour Party and moved the party radically to the right, chose to believe that Blair was doing it to neuter the media’s attacks on anyone who is to the left of Margaret Thatcher, and that once Labour was in power, he would move the party back to the left) I’m hoping that maybe McCartney has already drawn up the most incredible archive or everything he’s ever seen said done or felt, and has arranged for a decent biographer to write THE McCartney book once he’s died.

I mean, that fits with everything we know about how Paul McCartney works, right? Right?

You heard it here, Paul–get cracking!

I would very much like to see this, partly for selfish reasons (I want to KNOW), but also because it would show McCartney as fundamentally secure as regards his legacy. “So I had sixteen illegitimate children! I wrote ‘Hey Jude’, mofos!”

“So I had sixteen illegitimate children! I wrote ‘Hey Jude’, mofos!”

I really miss that little Thumbs Up button right about now. 😉

I mean, that’s pretty much the worst we know about him, right? That he couldn’t keep his dick in his pants? (And honestly… look at the guy. Who are we to judge?) Norman’s “shocking revelation” about the 3 girl + Paul orgy is like, not even remotely scandalous. That’s high-five material for a young man.

Norman talked about Paul having a 3-girl orgy? Where have I been? 😀

@Karen, I saw it on tumblr and then clicked on a link that took me to the blurb on whatever UK-tabloidy site (specific, huh?). I guess 1962 Paul told the foursome story to his cousin. 🙂 And again I say… what 20 year old wouldn’t a) jump at that opportunity and b) brag to his cousins about it afterward?

Ha—that’s like my memory too. I remember another quote from Paul (and of course can’t recall the source) where he said he wasn’t into that kind of thing. Maybe after he tried it he wasn’t that impressed. I’m sure a book alone could be written about the Beatles’ exploits.

(p.s. there’s this quote I’ve read in the blogosphere in which John called Paul a “sexual gladiator.” Don’t know if that’s true or not, but still kind of funny. 🙂 )

Well, @Chelsea, that’s why I’m a bit willing to remain ‘in the dark,’ was it were. Paul McCartney would be quite a rara avis if that was the extent of his shadow self — not if he were a normal dude, but because he’s a person who has made himself into Paul McCartney.

“Big bastards, that’s what the Beatles were. You had to be a bastard to make it man, and that’s a fact. And the Beatles were the biggest bastards on earth.” I don’t really need to know how exactly Paul is a bastard; I mean, if we learn it, I’d still like the music, but I don’t have a burning desire to know it — because I don’t really have a burning desire to get close to Paul. Those that do should be aware of the risk in that.

Y’know, I’ve always taken that quote of John’s with a large serving of salt. I’m sure fame required them to be kind of hard-nosed, and certainly they were young and naive enough to have done some insensitive things (the way in which Pete Best was fired, for example), but John always made is sound worse than I think it was.

@Michael and Karen, point taken from both. I’m sure there are plenty of things Paul doesn’t want us to know and WE don’t actually want to know. I mean, of course there are. I assume he’s a basically decent person, but I certainly don’t discount the possibility that he’s done disgraceful things or has really dark corners. That’s a safe assumption about anyone, IMO, but particularly powerful people.

My spouse has always based his impressions of a person on what that person’s kids say about him. Usually this is in terms of athletes and other celebrities, but he deals with lots of families through his work and this extends to us regular folk as well. 😉 Of course “kids” are people too and aren’t 100% unbiased, but he insists you can get a good idea of a person’s character through how their kids relate to them. That measure is a large part of what has formed my impression of Paul McCartney over the years. No matter what anyone else says, those kids love the crap out of their dad.

==>Gopnik consistently overplays his hand on this topic, saying for example, “In fairness to Klein, it should be said that few people imagined that the pop music of the period would be remembered eighteen months afterward, much less that it would still be hugely valuable half a century later.”

Another blow to the above Gopnik quote: In 1971, the music of the 1920’s, 1930’s and 1940’s (The Jazz age) had a huge following made up of people who were not even born when this pop music was recorded. I always thought that the music of the Beatles, Dylan and other 1960’s sources would last in the same manner.

In 1971, I went to see Duke Ellington. I had heard his music a million times in my childhood home. By age 19, I was just beginning to realize how gob smackingly fantastic some of the music of the swing era was, and still is.

In 1976, I not only saw Wings in the Seattle Kingdome, I also saw Benny Goodman at the Paramount theater in Seattle. Benny blew the roof off the house.

You essay has made me less inclined to read this book.

Thanks for your always-intelligent observations.

Thank YOU, @Ben! And I wish you would read the book, so I could hear your thoughts.

Okay Mister Mike, I shall give it a whirl and get back on this topic. Cheers

Well I’ll be dog! Dullbloggers…I have found that article regarding the aged Paul photo.

Google Curators: The shot that made me. Scroll down to Chris Floyd

Or click on: https://wwwcchrisfloyd.com/good-weekend-monday/

‘

I re-read the article. Where on earth did I get the impression that Chris Floyd was a woman, I don’t know. Maybe I just remembered wrong I guess. Anyway the article is worth a look, and ‘he’ has two photographs of Paul. The one I discribed and another which is also fabulous. Thank you guys for bearing with me.

Dang y’all! I can’t seem to do any thing right lately!

That’s: https://wwwchrisfloyd.com/good-weekend-monday/

It’s too damn early!

Oh my god, that was amazing. Thank you for sharing that, Water Falls! I felt dizzy reading that. Whew!

When I click on the link it says it can’t find the server. 🙁

Karen, you can google Curators: the shot that made me. Scroll down to Chris Floyd and click that link.

Just for the record folks, I do know how to spell “describe”. I guess I just spelled it the way I hear it and pronounce it, ’round this neck of the woods. Born an Okie.

No worries; I sometimes spell some words in Canadian french. 🙂

It’s just a typo in the URL, Karen. I got it by putting a dot in: https://www.chrisfloyd.com/good-weekend-monday/

thanks evilpants. Good catch.

Dullblog community, I hate to beat a dead horse, but I really must clean up a mess I made, correct a mistake and set things right. I’ve written a series of dis-jointed corrections of my original comment regarding the famous b/w photo of aged Paul by photographer Chris Floyd, based on 2 or 3 year old faulty recollection of the article I read by Floyd. Floyd is a man not a woman. I also provided a short conversation between Paul and Floyd, complete with quotation marks. The conversation I quoted, was based less on Floyd’s stated memory of their conversation, and more with the arc of Floyd’s frustration with Paul’s familiar standard poses. I conflated the two and mistakenly thought I quoted correctly. I had the gist of it, but was somewhat offbase. I also quoted “He hated me, and I loved him for it!”, which was correct, but the tense was wrong.

I just wanted to clear all that up, since I recommended you read Floyd’s article. Also the reaction of the ‘so far’ lone commenter on it.

Back in the early 1980s I was working for a small book publisher that specialized in mass market non-fiction. One day I saw a man I didn’t recognize. He was pounding away on a selectric typewriter, working from some scribbled notes he’d made from a variety of magazine and newspaper articles. My curiosity got the better of me, so I asked him what he was up to. He told me he was writing a biography of a famous rock musician.

What amazed me; what blew my mind was that he was typing away in our open floor noisy production space. At the time, I was struggling with writing a novel. I’d always thought of writing as a sacred act. Something one did in quiet isolation. And here was this guy, typing like crazy in the chaotic environment of our production department. He was obviously trying to beat a deadline. He had little or no understanding of or appreciation for the subject of his biography. It was a job for him.

Ever since that day, I’ve never looked at “rock biographies” the same way. 90% of them are pure bullshit.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSYtYCi1b2c In this appearance on Leno, from 2003, about 6 minutes in, Ringo remarks about how “Georgie loved to hug.” For two men who identify as straight, to be so emotionally close and open and not afraid of feelings is so beautiful. And I agree with the above, what would be the harm in exploring that angle of their friendship? One would think this would be a huge factor in the way they related to one another through the decades. George and Ringo are the Beatles I primarily want to know more about anyhow (not that all 4 weren’t enormously interesting and charismatic).

And I have no idea why that did not line up correctly under the appropriate conversation, (sorry)!

Newsweek has published an interview with Norman where the author traces his evolution on Paul:

http://www.newsweek.com/paul-mccartney-biography-philip-norman-beatles-454252?rx=us

“In 2013, Norman e-mailed McCartney saying he would like to write his biography as a companion to Lennon’s. He did not expect McCartney to collaborate with him, but he did ask for tacit approval so he could talk to the ex-Beatles friends and associates.” “‘Within a fortnight, I had a four line e-mail thanking me for my letter, saying he was happy to give tacit approval and wishing me all the best. Given what had gone before, it was magnanimous of him.”

Having read all three editions of Shout!, I’d argue that “magnanimous” is an understatement. Contrast this with Norman’s complaining in the first edition of Shout! that, when he approached Paul’s P.R. man about an interview, he got the equivalent of a “fuck off.” (Which he also got from John, George and Ringo’s people).

Paul’s ‘tacit’ approval is interesting to me, but there is precedent for it; Ray Coleman’s 1984 Lennon: The Definitive Biography is just as pro-John and anti-Paul as Shout!, but after Paul granted Coleman extensive interviews for his 1995 Paul pseudo-bio “Yesterday,” Coleman totally reversed himself. The role access plays in how Beatles history was written is an interesting one.

Ruth, thanks for that link. It’s nice to see Norman issuing a clear mea culpa for his earlier misreading of McCartney. I have to say it’s still hard for me to understand how Norman could ever have concluded that “Lennon was 75 percent of the Beatles,” given not only McCartney’s contributions, but also those of Harrison and Starr. In fact I think he also owes them an apology for the way he dismissed them in “Shout!”

That it evidently took Norman more than 30 years to work out that McCartney is driven because he’s insecure doesn’t give me the highest opinion of his insight, either.

@Ruth, these issues that you raise are precisely why it’s problematic to look at books like Shout! as history, rather than a sort of puffed-up journalism. I think only now with Lewisohn is this topic actually getting an historian’s treatment.

Then we will have to agree to disagree, because I believe judging such works is valid — obviously, as I wrote a book which applies historical methods standards to both primary and secondary sources, because they’re all part of the historiography.

Frankly, Michael, I see little point in having this discussion again. If you were under the impression that the purpose behind my original post was to prompt such a conversation, let me assure you it was not.

I agree, Ruth. Norman presented “Shout!” as history, and the publisher is still blurbing it as “the definitive work on the world’s most influential band.” (A statement for which there is not enough salt in the world’s mines to serve as accompaniment. )

WE can say — I believe correctly — that “Shout!” fails to meet the standards of history and should be considered highly-colored journalism. But many, many people have and do regard it as history, in no small part because Norman and his publishers have defined it as such. So I see the kind of judgment Ruth is making as entirely reasonable.

Also agree. Any book about one or all of the Beatles by a mainstream, recognized biographer is part of the historical record, and on that basis should be judged.