- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Beatles & Bournemouth

by Nick Churchill

176 pp.

Natula Publications, 2011

Reviewed by Devin McKinney

The swelling and significant subgenre of Beatles literature dealing with Beatles and place includes tourist guides like The Beatles’ London and The Beatles’ Liverpool that tell you where they walked and drank and sang, what alley, pub, or park backdropped a famous photo. There are books devoted to tours, like Larry Kane’s Ticket to Ride (North America, 1964), Barry Tashian’s Ticket to Ride (ditto, 1966), and Robert Whitaker’s mostly-photographic Eight Days a Week (Germany, Tokyo, Philippines, 1966)—in each of which, the cultural and commercial peculiarities of successive cities give detail and drama to the grind of jet engines and bus tires.

In town after town, they came, they played, they left. But the Beatles were really only the centering second act in a weeks-long drama that gripped each city. First act, the frenzies frothed up by fans, detractors, media, local hucksters; third act, the dazed aftermath, teenagers dreaming pillow dreams and promoters counting ticket stubs as the ringing in the town’s ears fades. This story is told in the small group of books about the Beatles’ hurricane effect on a single city. The first and best is still Eric Lefcowitz’s Tomorrow Never Knows, about the last concert, Candlestick Park ’66, the work of a self-described “pop archeologist” who, with the aid of Jim Marshall’s photography (the best backstage-onstage rock series, I daresay, ever), places the Beatles in their San Francisco context while retrieving the shreds of mystery and meaning that remind us the past never dies. Bill Carlson’s One Night Stand in the Heartland, about a 1965 visit to Minneapolis, is an attractive, impersonal photo album in which, among other goings-on, an odd Phil Spector look-alike seeks to crash the gate (the Midwest is not so predictable). I am curious to see Dave Schwensen’s The Beatles in Cleveland, if only because on the night of August 14, 1966, Cleveland Stadium saw the biggest Beatles riot ever.

They passed through so many cities, most of which they never got to see, and which never got to see them. The exceptions were mostly in the UK. In 1963, in their modest Mal-driven van, they blanketed England, Scotland, and Wales, from Elgin in the north to Bournemouth in the south. The mania was intense that year—not since the war had the sceptered isle been so consumed by a single invasive entity—yet there was still a hometown or at least home-counties quality to it. Fans were thrilled but not cannibalistic; venturing out in public, the Beatles feared for their hair, not their limbs. John Lennon later called this “the best period fame-wise. … We didn’t get mobbed so much.” Only when that same craze was loosed upon the world at large, exported to nations with entirely different inhibitions, freedoms, and native insanities, did the word “mania” assume its full implications.

Bournemouth, a 200-year-old resort city on Britain’s mid-southern coast, was one of the few towns lucky enough to have an intimate relationship with the Beatles, we find from Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Beatles & Bournemouth, Nick Churchill’s pretty-much-every-conceivable-angle examination. Intimacy like most concepts is relative, however, and here it means that the Beatles got many good looks at the city and its people, knew it as performers and as private citizens, and were photographed chomping its rock candy on the balcony of its biggest hotel. According to Churchill, formerly a reporter with the Bournemouth Daily Echo, this spot of earth is considered by most Britons to be “a retirement centre that only comes to life with the arrival of bucket-and-spade holidaymakers in the summer.” Churchill thinks that’s nonsense and so writes a book which “establishes the connection between the pop group that defined a decade and the part played in their story by a seaside town that’s not as quiet as it seems.”

Such Romantic-Decadent precursors to the Beatles as Wilde, Verlaine, and the Shelleys spent time in Bournemouth, finding rejuvenation in its breezes, inspiration in its proximity to water and cliffside. As the town grew into an affordable middle-class resort, it offered stage performers a lucrative stop on the touring trail; during and between the wars, many of the big names in middlebrow entertainment (Chevalier, Montovani) made their way to the local palladia. There was little or no indigenous rock ‘n’ roll scene, but package pop tours always came through and fans got to see most of the American heavies and British lightweights.

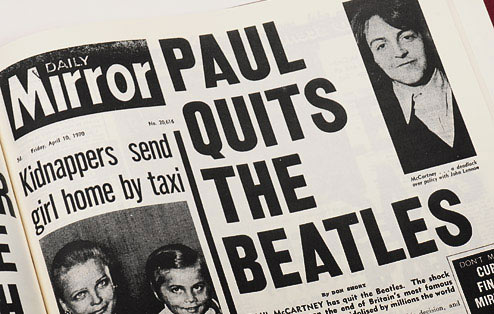

The Beatles went boom in early ’63, sending tremors to every corner of the UK, and for the rest of the year they worked their asses off to nurture tremors into quakes. Bournemouth got more of them than most places: The Beatles did a week’s residency at the Gaumont Cinema in August, during which a sick and crabby George Harrison wrote his first solo song, “Don’t Bother Me,” and the cover of With the Beatles was snapped in an empty hotel dining room, illuminated only by salty seaside sunlight pouring through enormous windows. They returned to headline at the Winter Gardens in November, and again the next year, while touring with Mary Wells. In September 1965, John bought Auntie Mimi a harbor’s-edge bungalow. Harry Epstein died in Bournemouth, of a heart attack, a mere six weeks or so before his son Brian caught the last ferry himself.

Nick Churchill’s depiction of the Gaumont week is particularly, and admirably, thick with detail, and from it come at least two nuggets of Beatles-historical interest. The first is the claim of several in attendance that, as Beatlemania had not quite yet hit its earsplitting pitch, it was still possible in summer ’63 to hear most of what the group sang and played. Unfortunately, we will probably not know for ourselves, which leads to nugget number two. A soundboard recording of one gig was made by the man in charge of sound for the Gaumont, a tape said by the few who have heard it to be first-rate. It was many years later sold at auction by the sound man’s daughter—sold, says Churchill’s witness, to an anonymous bidder representing Apple Corps. If that is true, the precious tape is now in a corporate vault from which, given Apple’s eyedropper release policy on unheard music, it will not escape until you and I have returned to dust, if even then.

In other eyewitness action, there is a nice story of a very young Al Stewart (a fave of your reviewer) talking his way into the Beatles’ dressing room by pretending to be a Rickenbacker representative. Churchill incorporates interviews with such previously untapped sources as Louise Cordet, a singer who appeared with the Beatles in Bournemouth; Tony Crawley, entertainment reporter for the Bournemouth Times; Eileen Denton, president of the local Beatles Fan Club branch; Howie Casey, who as leader of Howie & The Seniors shared the Beatles’ bills in Liverpool and in Hamburg, and years later recorded and toured with Wings; and any number of fans and functionaries whose recollections, frankly, tend to blur after a bit, partly from being pointlessly punched up with exclamation marks.

Churchill’s book is certainly justified by the frequency of Bournemouth recurrences in the Beatles’ chronicle, but its scope is necessarily specific, even granular. Were I reviewing it anywhere else I’d be required to note that its readership is the definition of niche, even more so than the London and Liverpool guides, for those cities’ claims on Beatles history don’t need justifying. Churchill has to tell us why Bournemouth particularly matters to Beatles fans, because we likely don’t know, or it won’t have occurred to us. But these are the Beatles, this is Hey Dullblog, and we, reader—you and I—are the niche. Let it be assumed that, if you are reading this, we both care about what a book like this offers.

That said, limits on scope likewise limit varieties of pleasure and interest. Churchill is not a critic or academic and ventures no new thoughts on the Beatles’ musical achievement or cultural meaning. He is a journalist and wants to assemble a narrative of past events from documentary and living evidences—news articles, photographs, interviews. That is fair, but even journalism can have personality, and Churchill’s prose is self-effacing to the degree that the text becomes only one production element among several. The others include photos, reproductions, captions, and text blocks full of info-bites you may either snack on along the way or consume as a batch, though the latter method is likely to leave you feeling bloated. Visually the book resembles a souvenir package, its margins crammed with record labels, handbills, posters, programs, stubs, and other ephemera. Anyone who grew up on the Carr-Tyler Beatles Illustrated Record will know the look, and like it at once.

Yeah Yeah Yeah will probably please you much as it did me, and it may leave you wishing, as it did me, that it were better. More interesting writing would have been welcome—wit, style, an ethic of surprise not just in the revelation of obscure information but in the grain of the wording itself. When there is nothing Bournemouthy going on, Churchill, seeking to construct a linear history rather than merely jump between highlights, fills in the gaps with potted Beatles history (albums, movies, breakup)—precisely what is most redundant for the highly-informed niche-dwellers who are his audience. But these are regrets, not active irritations, and Yeah Yeah Yeah really irks me in only one respect, which it shares with more books than can easily be counted. Writers on the Beatles must cease at once to name chapters (let alone books) after Beatles song titles, or lines of Beatles lyric. Must, but never will: Well-known lyrics are too ready a refuge, too easy a source of instant meaning or emotion for writers unconfident of producing those sensations on their own.

All quibbles and qualifications noted, there are none but positive observations left to make of Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Beatles & Bournemouth:

The book has an “Appendix” composed partly of Churchill’s brief descriptive appraisals of the acts that supported the Beatles on their Bournemouth shows. Here he gets some pop into his voice, some pith and opinion, and it’s the most entertaining writing of the book, as well as the most quirkily informative. On hapless Billy Baxter, a Liverpool comic who played the Gaumont during Beatles week: “The vast majority of fans ignored him.” Apparently a local duo, Gary and Lee, sought to piggy-back on two dance hits at once with their “Twistin’ to the Locomotion.” (Now that is what you call a lack of inspiration.) Another act was the Vernons Girls (sic), a vocal group revealed by YouTube to have been more or less England’s equivalent of the Angels (“My Boyfriend’s Back”), and utterly awful; so who’d have imagined the haunting, wailing backup on Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” was theirs?

I noted only three factual errors: “It’s the Same Old Song,” not “I Can’t Help Myself,” is the Four Tops record referenced in the Beatles’ 1965 Christmas disc; Yellow Submarine, the movie, was released in July 1968, not January 1969 (that’s the soundtrack album); and the Wings drummer was Denny Seiwell, not Danny. Three mistakes is a damned small number for any book (and the last might even be a typo).

Many of the photographs were taken by Harry Taylor, freelance shutterbug for Bournemouth papers. Most have been unpublished until now, and they are without exception wonderful, especially those with Beatles in them.

Before the Beatles, there were the Crickets, and in 1958 they did their invasion of the UK, playing at the Gaumont Theatre, the Odeon Theatre, and many other venues in London, Liverpool, Yorkshire, etc.

It’s impossible to hear Buddy Holly’s “I’m Gonna Love You Too” and not be reminded of “From Me To You”

Here’s a link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=leVS9j9nAH4

On the subject of Buddy Holly, the demo record (pre-fame) he made with Bob Montgomery “Down The Line” always reminded me of “The One After 909”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MuHctwcIhOw

-hologram sam

Breaking news:

“How a schoolboy recorded one of the earliest UK performances of the Beatles”

Here’s a link to the story:

https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-65167799