- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

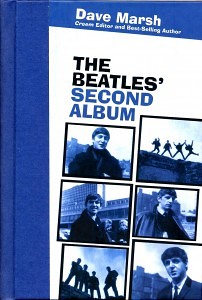

The Beatles’ Second Album

The Beatles’ Second Album

by Dave Marsh

186 pp.

Rodale Books, 2007

DEVIN McKINNEY • I’ve been reading Dave Marsh for many years, starting with his dozens of thumbnail critiques in the first two editions of The Rolling Stone Record Guide and his artist essays in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll; on through the reviews and journalism collected in Fortunate Son; uncollected pieces in old issues of Rolling Stone; and the massive compendium The Heart of Rock and Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles of All Time (one of my favorite music books, mainly because it anthologizes so many weird, delightful, improbable tales from pop days past).

But one thing I began to sense years ago is that no rock critic is remotely so driven by antipathy, animosity, and plain anger as Dave Marsh. Where that anger originates is anyone’s guess, but Marsh gives it release in his hatred of those who by his lights subvert or oppose the rock ‘n’ roll spirit—usually by being too avant-garde, serious, literary, or generally self-important. I would refer you to his guerilla raids on reputations he has felt to be inflated, be they those of Neil Young or Bono, Jim Morrison or Elvis Costello, Lou Reed or Pere Ubu.

There have always been angry critics: critics who are insulting, curmudgeonly, or pricky in transparently self-promoting ways. But Marsh, while he bears at least trace elements of all these ingredients, is seldom so easy to classify. When he expresses love of an artist or a record, the love is plain and real; and because his animosities and biases have always been on candid display, they’ve never seemed like elements of a con game. He never condescends to his reader, never pulls a punch, never tells a lie.

Which means he has all the virtues and limitations of an unmodulated bluntness. He doesn’t want you to misunderstand him; neither does he want anything much like artistry getting in the way of his polemics. If, as Ishmael Reed felt, writin’ is fightin’, Marsh is the Jersey Joe Walcott of rock critics—not a bad thing, but a rung or three down from the first rank. As a stylist, he floats like a tanker and stings like a mallet: his forthrightness and anti-crap stance can be bracing when you’re in the mood to be braced, but his writing lacks poetry, subtlety, irony, mystery, and many other good things that end in “y.” It isn’t Marsh’s style to critique by implication, undercut by aperçu, or deflate the grandiose with a well-placed pinprick of prose. His style is to club his victims with words like “pretentious” and “bullshit” and “idiot” and “asshole.” You’re left feeling certain where he stands, but you’re never haunted or dazzled; never troubled in the way that makes you return to a piece of writing again for new answers, or new questions. That’s one limitation of criticism—or of any writing—that is too direct, too unwilling to be ambiguous, difficult, or even cryptic: It’s not built to last.

Another is that there’s only one way to engage with it, and that’s head-on. Which brings us to this book.

* * *

It’s a slim volume, under 200 pages even with acknowledgments, annotated discography, and list of “Books by Dave Marsh.” In approach it is similar to the 33 1/3 series on “great albums” published by Continuum—a critical appreciation of a single LP. Given that no pop writer has yet succeeded in writing an entire book about the music alone, there is bound to be much back-story about how the LP was written and recorded, the personalities involved, its critical and commercial reception, all wired through and around the writer’s own apprehensions of the record’s significance as art and artifact.

The Beatles’ Second Album is a unique case for study, since it was not designed as an album by the artists, only made into one by their American record company. To recap what most Beatle fans know: Capitol Records, believing it had a short-lived sensation in the Beatles, rushed to release as much product as it could, as fast as it could. This resulted in a variety of albums, unique to the American market, which combined tracks from discrete LPs, singles, and EPs, reassembled without regard for running order, release dates, or other niceties; the same number of Beatles songs was spread over more albums, with fewer songs on each. This process continued through 1966, when the Beatles got tough and insisted that if Capitol wished to release their music in the future, it had better keep its meddling mitts off the band’s masters. By which time Capitol had graced their American canon with not just Second Album but Meet the Beatles!, Something New, and Beatles ’65, all in 1964 (that discounts the two-disc documentary set The Beatles’ Story); in 1965, The Early Beatles, Beatles IV, and the US versions of Help! and Rubber Soul; and in 1966, the US Revolver and the infamous Yesterday and Today.

It was all done for money, of course: Twice the product, twice the payoff. And the orthodoxy among hardcore Beatleheads since the 1970s has been that Capitol, in chasing that extra dollar, did a grave disservice to both the group and their American fans by so “butchering” the pristine UK albums. In not giving America the albums as the Beatles arranged and intended them, the orthodoxy goes, Capitol tendered a distorted picture of their artistic development. Compared to the Beatles’ innovative jacket art, Capitol’s covers were cheesy and simplistic. And not only were song selection and running order jimmied with, the master tapes of the Beatles’ songs were subjected to “equalization and enhancement” on arrival at the Capitol Tower in Hollywood—i.e., treated with immodest helpings of reverb and echo to “enlarge” the sound, bringing the Beatles’ sharp, dry Abbey Road ambiance more in line with what were perceived to be Stateside listening tastes.

Where the UK albums were at least nominally designed by the group itself, the US versions were the handiwork of one man, Dave Dexter, Jr. Dexter had been in the music business in some capacity since the ‘30s, writing on jazz in the early days of Down Beat, and appearing as a music panelist on New York radio. From there he’d gone into production, recording what Marsh concedes were some “pretty great” sides with Leadbelly, and putting together a well-regarded album called New American Jazz in 1944. By the ‘50s, though, his jazz prospects had dried up, and he eased sideways into an executive slot at Capitol, where he evidently irritated Frank Sinatra sufficiently to be barred from attending Ol’ Blue-Eyes’ recording sessions.

Dexter became Capitol’s head of international A&R in the late ‘50s—and in this capacity, he famously declined to pick up an option on the Beatles in 1963, not once but several times, at a point when they were a sensation in the British Isles but untried elsewhere. The impending crash of the band’s inevitable success forced others at Capitol to reverse Dexter’s shortsighted calls; but incredibly, Dexter—who not only thought the Beatles had no commercial potential, but didn’t even like the group—was made responsible for supervising their American releases. Whereupon, presumably chastened and more than a little resentful, he set about chopping up their master reels for maximum market yield, and fattening their lean sounds for the enhanced pleasure of the fat American ear.

Personally, I subscribed to the anti-Capitol orthodoxy until I was old enough to know what I was talking about. I grew up on those “Dexterized” albums, as they were still the American standard when I began collecting the Beatles in the late ‘70s—though British imports were by then sporadically available and in the mix as well. I have a childhood tie to the Capitol mutations, adore their “cheesy” covers, and appreciate that they collected numerous songs (“Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand,” “Bad Boy”) that were available in the UK, if at all, only as B-sides or obscure filler tracks. I even love Dexter’s cacophonous, pseudo-stereo remixings of the songs themselves: “I Feel Fine,” for instance, sounds like it was recorded in a cathedral, not a studio. And as a collector-geek, I love that Capitol gave me more albums, more jackets, more mixes, more dates and labels to play with, stare at, have fun with, dream about getting for Christmas. To say the Capitol albums should never have existed is, essentially, to say that there’s such a thing as too much Beatles—a point of satiety that I have, after 30 years of fandom, yet to reach.

Second Album in particular is a favorite—my favorite Beatles album, in fact, after the White Album. It has “She Loves You” and “Please Mister Postman,” incontestably my top picks from their pre-studio years. It has those other fantastically meaty, sensual Motown covers, “Money” and “You Really Got a Hold on Me”; angular, metal-harsh Lennon rockers in “You Can’t Do That” and “I Call Your Name”; George’s version of a great obscure girl-group side, the Donays’ “Devil in Her [His] Heart”; Paul’s essential threat to Little Richard, “Long Tall Sally”; and two amazing B-sides, “Thank You Girl” and “I’ll Get You.” The sole turkey, “Roll Over Beethoven,” at least gets over with fast. The album is loud, deep, dramatic, soulful, hard-edged, full of big love and low lust. For being a hodgepodge tossed together by a jazz-loving executive with no feel for rock or soul, it’s as close to a perfect rock ‘n’ soul LP as you can get. And it wouldn’t exist but for Dave Dexter, Jr.—who got many things wrong, but who got this one thing right by perfect, serendipitous accident.

* * *

Dave Marsh acknowledges all of this, more or less—except for that last bit. Dexter is this book’s villain, and, by force of the author’s compulsive attention, its true star. Unlike the Beatles, who are easy to love and tough to analyze, Dexter proves easy to loathe and impossible to shut up about. He is everything Dave Marsh hates; consequently, he is smack at the center of things. In contrast to hip Brit Paul White, Capitol’s man in Canada—who loved the Beatles early and plugged for them long before Ed Sullivan hunched into view—Marsh’s Dexter is an old-school hack executive with dated taste, a jazz snob and hater of rock, replacing vision and discernment with a “genuine stupidity about musical quality and, for that matter, the future of Western civilization.” Not only that: Adding insult to injury, Dexter responded to John Lennon’s murder by publishing, in Billboard, a “remembrance” that was almost all bitchery and bile. “Lennon’s Ego & Intransigence Irritated Those Who Knew Him,” ran the subhead over what Marsh calls “a bitter attack from a failed hanger-on.”

Dexter’s Capitol mutations, whatever their lack of propriety, decency, or respect for the art of the Beatles—something not even the Beatles were convinced existed at that early date—are lovable, explosive, crass, and exciting albums. Mutated or not, slick with stereophonic grease or not, they are the essence of pop as commerce and con game, gaud and gift, bang for the buck. But because Marsh so hates Dexter, he must make the case for hating Dexter’s mutations—though this is obviously counterintuitive to him, not least because he is at this moment making money writing a book about how great one of those mutations is. Repeatedly he finds himself in the contradictory position of lambasting Dexter while affirming that his butcheries had their peculiar virtues. The Second Album, he writes, “creates an image of the Beatles that is, arguably, closer to who they were … than anything else that leaked out to America in those heady first months.” Marsh hates Dexter’s addition of reverb and echo to the songs, but is compelled to pause in appreciation of Shelley Fabares’s “Johnny Angel,” where “there was something in the wistfulness with which she sang, and in the echo that surrounded her voice.” Marsh even comes close to crediting Dexter for giving his book the hook it needs, the substance he believes it has—before pulling back. “Maybe With the Beatles would have had the same effect” on American fans as the Second Album, Marsh theorizes. But “it wouldn’t have made nearly so good a story.”

But this isn’t really a story at all, only a protracted drubbing founded on personal animus and some sketchy historicizing. Every tit is answered with a tat, and sometimes they are equally questionable. Dexter claimed at various times—without corroboration and in defiance of logic—that the Beatles, and particularly John, had complimented him personally on the Capitol albums, their stellar sonics and imaginative presentation. To counter this presumptive lie (and enlist the Beatles as his comrades), Marsh revives the hoary idea that the Yesterday and Today “butcher cover” was conceived as a message from the Beatles to Capitol: to wit, Stop chopping up our albums. He negates any notion that the extensive 1966 photo session—of which the butcher shots were only one part—was seriously intended by either the Beatles or their photographer, Bob Whitaker, as a sequence of Surrealist-symbolist images, despite both Whitaker’s and Lennon’s statements to that effect: The “bullshit” stink of that offends Marsh. Then, lacking corroboration for his near-categorical claim, but still unwilling to attribute any artistic intent to the photo, he reminds us, correctly, that the Beatles invoked Vietnam carnage in defending its use as an album cover—“an interpretation,” as Bob Spitz says in his Beatles biography, “that was as facetious as it was unsupportable.” Anyway, doesn’t it strike Marsh that the Vietnam gambit makes hash of his own theory—or that it might be merely another, equally pungent grade of animal feces?

* * *

“The overall musical value of both the British and the American albums,” Marsh writes, “remains immense. What Dexter did was arrogant beyond question, though.” Maybe that’s the crux of it: Maybe it’s Dexter’s arrogance that Marsh can’t forgive. But it’s not as if pop, rock, and soul history were free of arrogant characters, or as if only jazz bred exaggerators and self-aggrandizers on the small-fry order of Dexter. No, it must be something other than arrogance, or the confabulations Dexter spread about his own achievements, that gets Marsh’s goat. It’s taste, judgment, prejudice, what the ears can’t or won’t hear. Dexter simply hated rock ‘n’ roll—he was quite up-front about that. And Marsh hates Dexter for hating rock ‘n’ roll.

Marsh is at pains to disclaim this bias, though. Dexter, he writes, “wasn’t an idiot because he didn’t like rock ‘n’ roll. He was an idiot because he used his hatred of rock ‘n’ roll to convince himself that the Beatles had no commercial potential.” But this is followed by a parenthesis: “[Dexter] seems to have deluded himself into believing that if only he and other gatekeepers would keep to sufficiently high standards, the big bands and his glory days would return on a golden cart from the cloudless heavens.” Which tends to invalidate Marsh’s disclaimer: If Dexter’s business acumen were the only thing at question, why the arch references to “big bands” and “glory days,” let alone the derisive hype about “carts” and “heavens”?

As frank a rock-hater as Dexter was, Marsh is equally intransigent when it comes to some forms of pre-rock American pop. His aversion, reiterated more than once, to the Beatles’ early recordings of “A Taste of Honey” and “Till There Was You” reflects a genuine, and more than comprehensible, dislike of the musical sources from which those songs spring—cabaret and Broadway, respectively. But that aversion is also clearly the product of a snobbery against any music that falls outside the proscribed range of rock-era pop styles—anything that one of Marsh’s elders might once have held up, in contrast to Little Richard, Elvis, or the Beatles, as “legitimate” music. Marsh stamps the songs repeatedly as “rubbish,” assuming that his reader is sufficiently like-minded to forgive the absence of any critique to prop up that curiously affected usage.

The jerk of the knee always short-circuits critical engagement. I detest cabaret and Broadway nearly as much as Marsh does; yet I treasure those two Beatles recordings. I don’t care for the songs themselves (versions by others bore me stiff), but I love what the Beatles do with them. Their wintry “Taste of Honey” tastes more like quicksilver, with its minor key, bitter guitar, and eerie third-person backing vocals. “Till There Was You” has not only a vocal of surpassing freshness from Paul, but one of George’s loveliest guitar solos. Both are expressions of identity and cultural affinity as integral and unphony, I would argue, as anything the Beatles recorded in the early days. The fact that Marsh’s hatred of the songs’ generic origins precludes any consideration of them as Beatles performances points to one of his limits as a critic: To him, the mere entertaining of non-rock material proves the sin of inauthenticity.

To a degree, critics are to be granted their prejudices, for out of them come point of view and personal voice. Anyway, as Marsh says, he is “not here to be entirely fair.” If only he weren’t so gratuitously unforgiving of Dave Dexter’s biases of taste and judgment. If only he weren’t so pitiless; if only he knew when enough was enough, or didn’t mistake a prolonged personal attack for “a good story.” Near the end, Marsh offers a terse recap of the Dexter saga:

The journey he took involves the frustration of becoming a cog in a big corporation, which is what Capitol was by the early 1960s; of having great ambitions as a writer, reporter, producer, and talent scout and realizing none of them; of being a parent of teenagers who (he makes clear) rejected his musical taste, which to him meant they sided with the enemy; who’s got a history that includes watching Down Beat deteriorate, New American Jazz flop in the marketplace, and being damaged personally and professionally by Sinatra’s refusal to even let him hang around his session; who’s steered into a corner at work and reduced to bragging about the sales of the German beer-drinking music album.

The Dexter saga: A talented man whose aspirations are stymied or stunted by who knows what combination of chance, personality, limitation, and fate; who goes from in-demand jazz commentator to hot-shot record producer, from high-ranking but anonymous executive to has-been in the office down the hall. Anyone but Marsh might find a degree of pathos in that narrative, or at least wince sympathetically at the sting of poetic justice.

* * *

The paragraph quoted above is followed directly by a breathtaking instant of self-exposure: “For me,” Marsh writes, “to see this sour Dave Dexter, Jr. is to remember the face of my father.”

My marginal note at that point: Marsh comes clean? Could this explain the gouts of contempt he sprays at Dexter’s ghost, the extremity of which have by this late point rendered the book irretrievably unpleasant? Marsh has written more than once about his father, a Rust Belt racist (“angry,” “square,” “rednecked”) who hated rock ‘n’ roll, belittled his son for loving it, and withal was a working-class exemplar of “jaundiced snobbery and proud ignorance.” Now, father-hatred could be a compelling psychological explanation for the anti-Dexter excess. But no. Marsh lets fall the clear implication, refusing to follow up the psychic connection he himself has made, and to which the reader is inevitably drawn—if only because its suggestion of the hidden is more interesting than anything Marsh has made visible. Far from coming clean, he is only gathering his forces for another sustained, multi-page, multi-point, quite well-researched, and, as regards the Beatles, pointless dissertation on the one-person plague that was Dave Dexter, Jr.

It may occur to a reader, following on Marsh’s projection of Dexter onto his father, that the real connection—the deep, dark, unspeakable affinity—is in fact between the two Daves. That Dave Marsh sees in Dave Dexter a man somewhat like himself—a true-born lover of music (albeit the “wrong” music); a writer who straddles journalism and criticism, corporation and nightclub, who has dabbled in production and promotion; a man of fierce, often wrongheaded opinions who remains, to the end, intransigent and unrepentant. Perhaps if Dave Dexter had been a rock man instead of a jazz man, Marsh might even have admired him a bit; might have forgiven him an exaggeration or two, or extended him some pity. Given that neither the Beatles nor their fans were harmed by his shenanigans, that we all in fact benefited in some degree by them, and that history had pretty much forgotten Dave Dexter before this rancid resurrection, pity doesn’t seem so much to ask.

* * *

That Marsh ends the book with several flavorless pages on the Second Album songs (“Building Complexity Out of Simplicity” is his unstartling theme) does not help the whole go down easier. What a reader will take away from this book is the attack, not the embrace; Marsh’s hatred of a man and a mentality, not his love of a band and a spirit. “[Dexter] tried to get out of the way of rock ‘n’ roll and it just steamrollered his ass.” Such cackle and gloat as Marsh imagines his villain’s dishonorable demise—such unholy glee. But no fun at all.

That is the bottom line: The book is no fun. None. It is almost relentlessly sour, carping, and petty. Come to the music, Marsh has nothing very original to say, and certainly nothing inspiring: Nowhere are you gripped by the need to rehear these familiar songs in the light of what the writer has heard in them. It’s not outlandish to say—amid all his inveighing against the sins of others—that he has sinned by writing a book that is ostensibly about one of the most exhilarating albums ever waxed, by the happiest foursome that ever assembled itself, and instilling it with virtually nothing but bitching and bad feeling.

It may be that Marsh planned to write a lengthy appreciation of The Beatles’ Second Album but found that, without the Dexter attack as his centerpiece, he didn’t know what to write. Maybe he has been wanting to “do” Dexter for years, ever since the Billboard calumny. Either way, he has used this book mainly as the excuse to settle an unsavory score, one which can have only minimal interest to readers—most of whom will feel that the Beatles’ music, not to say their own desires for refreshed pleasure and deepened discovery, have been cheated.

“In print,” Marsh writes of the other Dave, “he comes across as a nasty, vindictive son of a bitch.” I grant Marsh the respect of assuming he sent his book to print fully aware of how easily that might be applied not just to his target, but to himself.

Sharp post–the book sounds hideously unpleasant.

When I read Marsh, I always find myself wanting, like the bystander to a climactic fistfight in a movie, to take him aside, shake him by the shoulders, and say, “We’ve won, Dave. We won. People respect the music we love now. Our side won. You don’t have to keep fighting.” His abrasiveness even mars The Heart of Rock and Soul, which for the most part is one big blast of appreciation. (I suppose it would be unkind to mention his inclusion of “We Are the World.”)

I felt a similar urge reading Will Friedwald’s book about Sinatra’s arrangers: he’s so dismissive of rock music that he totally misreads Sinatra’s brief duet with Elvis on “Love Me Tender/Witchcraft,” a moment that is pure loose, goofy fun. I just want to sit him down and make him really listen to what Elvis is doing . . . but I don’t have to: somebody got to him, and he recently wrote about how great Elvis’s gospel records are!

(Oh, an in case you haven’t heard it, I’d recommend Sarah Vaughn’s version of “Taste of Honey,” from Sarah Sings Soulfully. It’s far from the best song on that record, but it’s lovely.)

Top-notch stuff, McKinney.

Great post, Devin.

I found an interview with a suitably crabby and unsympathetic Dave Dexter here. Wasn’t Albert Goldman also a jazz aficionado with a grudge against rock? I seem to recall reading that somewhere, maybe in Luc Sante’s piece about Lives of John Lennon in the NYREV.

My attitude about critics is this: “If you love God, beware of priests.” That’s not to say that I didn’t do a fair piece of book reviewing back in the day; I like to think I hipped some people to the better examples of written humor, and steered them clear of the shoddier ones. But I had to quit. I realized that the more intense my opinion was towards someone else’s art, the more likely it was that I wasn’t addressing their work at all, but some aspect of or about myself.

Some people can critique without it becoming a snap referendum on themselves, but I can’t. And neither, from what Devin writes, can Marsh. A book about his father probably would’ve been a more interesting book–certainly a more honest, human, visceral one than an extended hit piece about a clueless functionary.

When Dave Marsh is lambasting someone for their sins, could he be yelling at himself? Who knows? But it’s a fascinating thought, more compelling to me by far.

From “Howling Rabbit,” posted on the old Blogger site…really gotta put a redirect there or something…

“Being an American Beatles nut, I grew up with their Capitol albums and feel a closer kinship with them than with their “authentic” British releases. That said, I have made some changes to the sequencing of a couple of their American albums for my mp3 player. For The Beatles’ 2nd Album, I put “You Can’t Do That” before “Roll Over Beethoven” and I also switched places between “She Loves You” and “I’ll Get You.”

The only other album I altered was Beatles VI but my changes for this one are quite radical!”

Devin, you break my heart! “Roll Over Beethoven” a turkey?! How can you resist the soul-slapping rhythm guitar of John Lennon mercilessly driving the song? How not love that wonderful alteration in the bass line in the last verse? And let us not forget the place of “Roll Over Beethoven” as one of the songs that shocked Capitol in general and Dave Dexter in particular by becoming yet another hit for the Beatles in those all important first months of the American strain of Beatlemania! (you can’t go by the Billboard charting because of the Canadian single’s exclusion from the rating, the EP Four by the Beatles inclusion, and the tremendous sales of the LP itself) Indeed, “The Beatles’ Second Album” IS the greatest and perfect Rock ‘n’ Soul LP of all time. (Of course, that’s just my opinion… Horses for courses… :D)

Being British, my main exposure to The Beatles as a kid was through the British records – original releases passed down to me from my grandmother. I adored them. One day my dad bought me a copy of The Beatles’ Second Album from a crappy market stall in Bulwell in Nottingham (this’d be around 1979 when I was eight). It was the first Beatles album that was mine alone, bought just for me. So that was the first reason to treasure it. Then there was its exoticness (a little seen American album!) and weirdness: even as a kid I knew that The Beatles were all about quality. The sleeves, for instance, all looked great: particularly With The Beatles and Beatles For Sale. But the Second Album’s sleeve is utterly charming in its cack-handedness. It looks just like the sort of record you’d expect a big, corporate record company to put together in order to make money. I loved that – that it was outside of what I thought The Beatles were all about. Finally, and mainly, the greatest thing about it is the music. Pure energy, pure joy and the very essence of the Beatlemania sound – particularly through John’s voice. Marsh is right about Money, as was Greil Marcus before him: “It delivered everything that rock ‘n’ roll had promised.” (Or whatever the quote was.) And all of this great, urgent music sounded (through my shitty record player) even more urgent and alive as a result of Dexter’s fiddling. It fair blasted out of my record player and made the British equivalents sound a little tame. Just marvellous.

Anyway… the first couple of chapters of the book are fine because it seems we’re going to be heading into a journey of grandiose sentimentality and myth-making (which is how I tend to approach The Beatles). But then it quickly turns into something much more pedestrian and petty. The stuff on Dexter is just nasty, Not just from what Marsh writes but the way he keeps repeating it. Dexter may have been a cloth-eared clod but, however much Marsh tries, I can’t take him seriously as a villain. Mainly because he wasn’t a villain. By the end of it all I despised Marsh much more than Dexter.

In all, it’s a rather pointless little book. It’s not even as if Marsh writes well about the songs – he’s got nothing interesting or insightful to say on that front. The book’s only saving grace is in its very existence: because it reminds us that the Second Album deserves a bit of attention and love.

Great comment, @Paul. Comment more!

FWIW, I too love The Beatles’ Second Album. It is a time-capsule, for all the reasons you state.

Me too, if it wasn’t clear from my review. (Can’t say it often enough.)

@Michael. Thanks Michael. Would love to comment more – time permitting. I’ve read through a few of the posts on this site and they’ve all been excellent. I’m not sure who’s behind heydullblog but, whoever it is, they deserve a big pat on the back. Great stuff.

I’ve just discovered this site and am delighted. I do want to just mention — anger can, and should, be a source for creativity and achievement. (Witness, for example, the career of John Lennon.) I don’t see any merit in critiquing a writer based on said writer’s rage. Upon reading this review, some people may feel that Marsh’s anger is sad or unfortunate or a waste of energy or whatever. (I’m not sure that’s what’s being said in the review but some people will interpret it that way.) Not at all. It’s his wellspring. The risk, of course, is generating sourness. (“By the end of it all I despised Marsh,” writes a commentator — good God, really??) I’m looking forward to reading The Beatles Second Album to see if sourness and despicability are, in fact, its essence.

Welcome, Bob! If you read some of Devin’s previous posts, I think you’ll find that he agrees that anger can be a source of creativity and achievement. In this post I hear Devin critiquing the way Marsh is dealing with his anger (or not dealing with it, in the sense of not getting at the root of it) in this particular book.

I cannot believe that Devin McKinney is calling the Fabs’ first-rate cover of “Roll Over Beethoven” the “sole turkey” on the ‘Second Album’. Are you kidding ?? It sounds like the Beatles are back in the Cavern or the Star Club with the sweat running down the walls, and it rocks like mad. It’s one of the band’s best covers in my opinion, just as good if not better than Mr. Berry’s original. In any case, the problem I have with Dave Marsh’s writings as a rock critic is that he lets his personal biases affect his conclusions way too much. With Marsh, he feels that anything by Springsteen or the Who is great, anything post-1971 by the Stones sucks, he was only half-heartedly approving of the great original punk/new wave bands in the late ’70’s, anything soul or disco-oriented and recorded in Detroit is great, etc. His writing is discouraging, whereas a rock critic like Greil Marcus is far more objective.

I mean, I absolutely love both Springsteen and the Who, but unlike Marsh, I’m not about to say that everything they’ve released is great !