- Needed: Paid Research Assistant(s) for a Beatle Project - October 28, 2023

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

Commenter CMO#9 writes (slightly edited by me):

I’ve been reading the latest issue of Vanity Fair and there is a profile of the late war correspondent Marie Colvin. The article mentions that growing up, Colvin idolized The New York Times war correspondent Gloria Emerson.

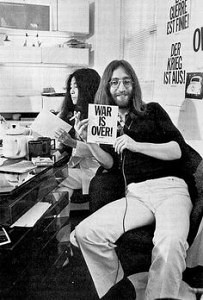

That name should ring a bell for some of you and I have no doubt that you are familiar with her brief but polarizing entry into John’s life, Michael. I believe it was either 1969 or 1970 when Ms. Emerson interviewed John (and Yoko) at Apple. She basically calls him a fool for him believing that his songs and slogans could and would change the world. I used to feel Ms. Emerson was living in the past, a relic left over from the previous generation and clinging to relevance by publicly challenging a Beatle. I think my opinion began to change with something that you (Michael) wrote on Hey Dullblog. You felt that John made the conscious decision to appear and be taken more seriously towards the end of the Beatles. He believed, as you stated, that in the future (aka now) his participation in marches and demonstrations would be remembered more fondly and admiringly than to a video of him bopping his head along to “She Loves You.” But do you agree with Ms. Emerson?

My response to this is too long for the comments, and I expect a lively back-and-forth, so I’m putting it up as a post.

Watching this again, I’d like to agree with John and Yoko—I’m a comedy writer, not a war correspondent—but I think that Gloria Emerson has been proven correct. Yoko’s point at the end is particularly wince-worthy: “Can you imagine anybody killing someone with a smile on their face?” My god. And I think it’s really interesting how defensive Lennon gets—how he stops trying to connect with her almost immediately, and starts using buzzwords like “middle-class” and “fascist.” He knows he’s playacting, but his ego won’t let him stay calm. Emerson’s no better—”dear boy” ugh—but the intervening 44 years has made her points weather better than Lennon’s. And I want to emphasize that, as a comedy writer (our era’s version of a protest singer), I want to agree with Lennon. I want to think my jokes can change the world, just like he wanted to think his songs could.

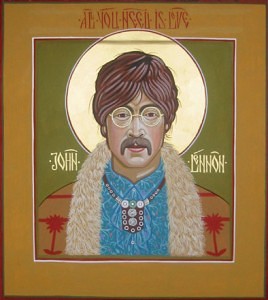

But that’s not what the history tells me. My opinion on Lennon as a peace activist is based on nothing more than public sources—I don’t claim any special insight—and it’s idiosyncratic enough to have pissed-off many of my friends in progressive politics. Most not only wholly buy the St. John myth, but see it as a model of virtuous, effective political action in the media age.

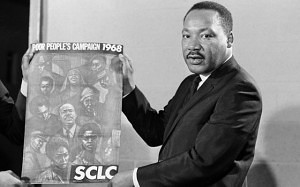

The conventional wisdom is that John and Yoko simultaneously led and followed a mass social uprising of youth which ended the Vietnam War. And that John’s future status, his icon-hood, is built on this vision of him as a Man of Peace, similar to Gandhi or Martin Luther King. I think all of this is, if not exactly bullshit, then a questionable reading of the history of the time. It’s very romantic, and very flattering to ex-Movement types now residing in academia, and neither of those things are a big deal. The big deal is that it’s derailed liberalism ever since, and turned it from a largely effective, somewhat unified political force to a largely ineffective, fractured one.

Sincere, but wrong

Did they want it? Sure — sorta.

I think John Lennon was absolutely sincere in his desire for peace; the Bed-Ins were rooted in a psychological need that was always there, kindled by the immense upheaval he went through in 1968-69. But I think that his basic assumptions are flawed. I think he (very understandably) overestimated the power of cultural figures in general and himself in particular. I don’t think war exists just because the masses don’t demand peace; often the masses are the ones demanding war (see: WWI, Niall Ferguson notwithstanding). And I don’t think you can “sell peace like soap,” because peace—even if Lennon ever had taken the time to define it, which he never really did—isn’t a product that can be exchanged for money, it’s an idea.

The power of a “sale” comes from the money that exchanges hands; I buy a Dixie cup, and the Koch Brothers get a dime’s worth of frozen power from me. John and Yoko’s “peace” had to be defined into some real-world action injuring the baddies and/or helping the good guys. You have to not pay the salt tax, or not ride the buses, or fill the jails, or enroll in the University. John and Yoko shied away from this, and they said exactly why: people who do that get shot. So what John and Yoko were doing was performance art, not politics. As “happenings,” their activities were very successful, but they did not make the world more peaceful then or now, and had zero measurable impact on the struggle to end the Vietnam War.

Ideas are powerful, but it’s incumbent on a leader to offer that next step—“if you believe in idea x, then do y”—and if by doing y, people get x, society changes. John Lennon telling kids who are about to go to Vietnam “grow your hair for peace” is like FDR saying to people in the breadline “grow your hair for prosperity.” Ideas are something, but it’s peculiar to suddenly think that they’re the only thing, and this attitude isn’t present before the guns started ringing out. Symbolic action is, by 1969, a substitute for the leaders that aren’t there—from conventional ones like JFK and RFK, to more radical ones like MLK and Malcolm X.

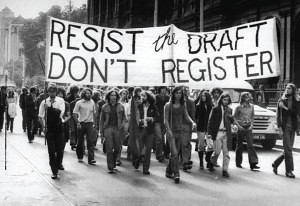

By the time of the Bed-Ins, no American male of draftable age needed a John Lennon song to “Give Peace a Chance”; they had the immensely more real threat of being drafted and dying in a rice paddy. That’s what motivated the mass demonstrations from the Mobe on; and we know this because when the draft stopped, the marches stopped. (In fact, the whole thing we call “the Sixties” stopped.)

What Stopped the War?

When the draft ended, so did the Movement.

So, if not John and Yoko, what stopped the War? My belief is that, after Tet, a significant number of the power elite began to believe that we could not “win” in Vietnam, and that the economic impact of an endless quagmire was too great. If we couldn’t win, and staying was bad for business, the only reason to keep fighting was an implacable fear of Communism—which detente showed was waning. The anti-war movement, while undoubtedly a powerful personal experience, and an undeniable cultural shift, doesn’t seem to have made much of a political impact. Unlike Reconstruction or Progressivism or the New Deal or Civil Rights, the New Left didn’t get anybody elected (cough George McGovern 1972 cough), and didn’t change US policy or laws. The moment the immediate personal threat was removed, its members dispersed. “The Movement” was Vietnam; and all the other parts of it, from brown rice to drug humor, were immediately and seamlessly incorporated into mainstream capitalist culture without a hiccup.

And yet, the Left still really believes in leaderless, ill-defined, transitory mass displays of opinion as effective political action. This is an immensely appealing idea that simply seems unsupported by data, either in the individual case (remember all the people who marched against the second Iraq war?) or in the mid- or longterm view of American politics. Today the US is more culturally progressive, and more politically right-wing, than it’s even been. The personal simply isn’t the political, and once you get rid of that shibboleth, things make a lot more sense.

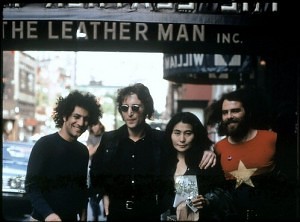

An Idiosyncratic Commitment

Down in the Village with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, before things soured.

Lennon’s peace activism was entirely—100%—personal. He supported no political candidates, disliked the New Left leaders he came in contact with (he thought were using him), and did not follow through on any of his pledges to mobilize his personal popularity into votes. I can’t blame him, because the world was strangely full of “lone nuts,” and by 1971, the FBI was making it clear that powerful people had taken an interest. He was both prominent enough to be in trouble, but not effective enough for the trouble to be worth it.

The only way John Lennon’s political commitment could’ve stood up under that kind of pressure, was for it to have flowed from a deeply felt, rocksolid set of personal beliefs. That wasn’t his nature. Unlike Gandhi and Martin Luther King and Malcolm X (and maybe even JFK and RFK, if you believe Jim Douglass), Lennon’s activities did not take place in, or grow from, any well-defined tradition, religion, or anything more than what he wanted to do that Tuesday morning. In this, Gloria Emerson was right. But she was wrong to think he was insincere. They were, while deeply felt and well-meaning, fundamentally narcissistic, and when he moved on to Primal Scream, he’d moved on.

Why War? Why A Roomful of Fur Coats?

In 1967, King publicly opposed the War, and devised his last crusade: a Poor People’s Campaign.

Lennon was never brave enough to acknowledge that modern war is rooted in the scarcity mindset of capitalism—that is why both Gandhi and King and Malcolm X lived (and died) as poor men. Lennon was calling for everyone else to make a better world, while he enjoyed every possible benefit and protection of this one; there simply is not enough moral authority there. It didn’t work when he did it in 1969; it doesn’t work when Yoko or Bono or [insert celebrity here] do it now. It’s merely a symbolic gesture, and if one takes it seriously, it’s apt to be actively irritating. Don’t ask me to buy your latest single so that people in Ethiopia can have a meal; give your money, and ask me to give mine; and hungerstrike until the UN sends relief. Do something real, with real consequences for you personally; otherwise, it’s just talk, and that goes for me, too. Unlike the Jesus comment—which was not a calculated political action—Lennon lost nothing, risked nothing, with his Bed-Ins. The people who liked him would like him; and the people whose respect he’d lose—like Gloria Emerson—he didn’t care about. Does anybody know of any valued friend Lennon lost over his peace activities? I can’t think of one. He was, via the world’s media, talking to himself. But it was harmless, and who knows, maybe it inspires/d others to do real stuff. That’s great, but the kudos should go to them, the ones who risk, not the rockstars doing what rockstars do (write songs, give interviews). That most rockstars are horrible clods doesn’t make John Lennon a Saint, and for my money he’s not even the most virtuous rockstar in The Beatles.

Only the Political is the Political

Saint John Lennon

Which leads me to my final point, and the only real bone I have to pick with John Lennon on this matter. I’m glad he was “for peace.” I’m “for peace,” too. But as it turns out, the personal isn’t the political, only the political is the political; the Left has spent the forty-four years since 1968 marching, making scathing movies, cracking endless jokes—and has less power than ever. As Mort Sahl said, “The right’s taken everything, left us Hollywood, and convinced us we won.” The Bed-Ins hastened the emergence of (seemingly) virtuous consumption, which is the economic equivalent of f**king for chastity. What the 60s counterculture got right was that the dehumanizing horrors of modern life are inextricably linked to our desire for more, more, more, on a planet of finite resources. You don’t make the world a better place by buying stuff—but that is the mass-cult application of what John and Yoko were doing in 1969. They were saying that right attitude, not right actions, mattered; that you could change everything without changing yourself. That wasn’t true in 1969 and it’s not true now.

Fascinating post. So much to think about.

And I think it’s really interesting how defensive Lennon gets—how he stops trying to connect with her almost immediately, and starts using buzzwords like “middle-class” and “fascist.” He knows he’s playacting, but his ego won’t let him stay calm. Emerson’s no better—”dear boy” ugh—but the intervening 44 years has made her points weather better than Lennon’s.

John’s demeanor is what bothers me most about this clip. He obviously cannot tolerate being challenged, and that’s disappointing.

You’d think, if his motivation was really more peace- than ego-oriented, that when faced with a critic who has actually DONE STUFF and SEEN STUFF and who really has skin the game, he’d spend less time defending the wisdom and efficacy of his chosen course and instead say something like, “Hey, you could be right that this isn’t the most productive method. What do you suggest?”

But no; John’s opinions and actions were centered so overwhelmingly around HIS feelings, HIS needs, HIS perspective (and, yes, his momentary hare-brained whims), that it didn’t leave a whole lot of room for things like, oh, critical thinking skills or intellectual rigor. That’s not such a bad thing, per se (it’s part of what made him such a brilliant artist), but it leaves him rather lacking in the political leader department.

I believe it was you who said in an earlier post that John wasn’t so much a leader of the peace movement as its mascot. And there’s nothing wrong with that; the world needs mascots, too. But it’s a bad day when the guy in the purple dog costume mistakes himself for the coach — or worse yet, when the players do.

Ultimately, I can’t help but think that John would have been a more powerful force for good in the world if he had concentrated on making art, as well and as purely as he knew how.

OTOH, what, I’m ragging on Lennon for not doing MORE for the world?! Pffft. (How middle-class of me.) 😉

Thanks again for the great post!

Interesting read. This thread may get hot but then, no guts no glory. 🙂

“So what John and Yoko were doing was performance art, not politics. As “happenings,” their activities were very successful, but they did not make the world more peaceful then or now, and had zero measurable impact on the struggle to end the Vietnam War.”

Precisely. Too often, the purpose of their performance art seemed as much to promote John and Yoko as it was to promote “peace.” So many of their stunts were so pointless. John Lennon was a smart man but he was not an intellectual or a politician or an activist. He didn’t have the interest or commitment to truly “get involved” in a sustained, practical way in politics. He got bored of that gig very quickly. And he also found out it was bad for business as his record sales slumped throughout the 70’s. Don’t get me wrong: I’m sure John believed what he was saying. But I have always had the sneaking suspicion that his dalliance with the left was partly just a way to put the spotlight on himself. He liked the rep and the attention. And Yoko continues to do things that have no practical impact — like spending a lot of money to light her Imagine Peace tower in Iceland that always brings her a lot of publicity but doesn’t achieve anything else.

In the end, though, John’s actual, practical impact on progressive politics or on politics in general was, as you say, negligible. Nothing he or Yoko ever did brought us any closer to “peace” — then or now. It did, however, years later help Yoko establish their brand, and sell a boatload of Imagine-themed T-shirts and umbrellas. But that’s just the cynic in me talking, I suppose.

The biggest irony in all of this is that the only Beatle who actually had a real and lasting influence on a social and political issue — in a progressive, practical way — is Paul. Paul’s decades of steady quiet activism on behalf of vegetarianism and animal-rights took a fringe issue in the 70’s and made it seem mainstream to a whole lot of his fans globally who were not rabid leftists but were middle of the road politically. I would liken Paul’s influence in spreading vegetarianism to Nixon going to China: If Paul McCartney was doing this vegetarian thing, it must be “normal.” It must be OK. Influencing the way we eat and getting people to think about how food gets to our table is a highly political issue, and the McCartneys arguably had more influence globally on that issue than any other celebrity. And Paul is still out there with his Meat Free Mondays campaign, talking about climate change, supporting the Greenpeace campaign against drilling in the Arctic, going to Canada to perform and speaking out against seal hunting, going to do a concert in France recently and urging the French to allow veggie options in school lunches, and taking public stands on animal rights issues (most recently in favor of a ban on testing cosmetics on animals). All practical, pragmatic stances.

Paul never gets much credit for any of that influence from progressives. Funny, eh?

— Drew

Yikes! I didn’t mean to bring politics into the blog, but I guess I should’ve realized it might happen.

Thanks for responding, Michael.

So many good points made by Mike and both Annie and Drew as well. I don’t love this sentence, however:

“In the end, though, John’s actual, practical impact on progressive politics or on politics in general was, as you say, negligible. Nothing he or Yoko ever did brought us any closer to “peace” — then or now.”

-Drew, while I believe you are mostly correct on this issue, it’s tone is bordering on the ‘pessimistic, why bother’ sentiment that I absolutely hate. The overly pessimistic and negative feelings people seem to have regarding this particular issue really bothers me. So John didn’t do all he might’ve or could’ve? Perhaps he wasn’t as invested as we would’ve liked. Maybe he didn’t accomplish anything afterall. So what, I ask? He put himself out there, and advocated peace and understanding throughout the world. No matter how corny or naiive it sounds or actually is, I still admire it and think John was doing something positive. Who wants the celebrities we have today who refuse to say or do anything that might possibly alienate a percentage of their designated demographic? Not me. Give me the John Lennons of the world every time. (not trying to say that this is how you feel, Drew, I just used your comment as an example of negativity which I dislike)

“Ultimately, I can’t help but think that John would have been a more powerful force for good in the world if he had concentrated on making art, as well and as purely as he knew how. “

-Annie, this is something I meant to include in my original question but seem to have forgotten. Thanks for bringing it up! It’s something Michael has touched on earlier and it’s fascinating to think about. What would John have accomplished if he had said “screw this peace sh*t” and went full-on into trying to create some more amazing and classic music? Alas, it wasn’t meant to be, but fun to imagine a separate world where this occurred.

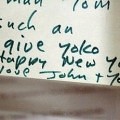

Anyone ever get in a (sexual) relationship with someone in which you are so enamored with and/or insecure at the same time around that person? You try to do anything you can to impress them and show them you are a truly great guy/girl. You do things you would ordinarily never do, never even consider doing if not for that person. Was Yoko this person to John? (random little theory I just started to shoot around in my head, I’m sure it’s been discussed before)

-Craig

The comparison of John and Paul as avatars of change put me in mind of this line from the movie, “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story”…

Paul Rudd (as John Lennon, pointing to Jack Black, as Paul McCartney): “I write songs about peace and love. He writes Sussudio.”

In my humble and respectful opinion, many of you dullbloggers are too cynical when it comes to John and his peacenikking and pontificating days of the ’70s. What he said and did should be put in the context of the spirit of the times and should be looked at with affection for his genuine passion mixed with idealistic naivete. Yes, he sometimes took himself too seriously (though sometimes he didn’t, as well), but how many of us have ever been handed the world stage in our 20s? At least John decided to try and do something positive with his position.

If you’re disappointed by John’s defensiveness in the video, what about Emerson’s rudeness? She was not just challenging him, she was straight-out attacking him: “What do YOU know about a peace movement?” and “You’re a fake!”

Remember that John himself had mellowed a bit by age 40, but he never abandoned his ideals. One of the last things he said to us was, “It’s not out of our control. I still believe in love, peace. I still believe in positive thinking. While there’s life, there’s hope.” I was 17 when I taped that interview off the radio (still have the Memorex cassettes!), and those words stick with me to this day, they still inspire me.

He never claimed to have THE answer, just the passion to try and find some truth and the guts to share it with us when he thought he had found some. Could he be overbearing at times? Sure… but he could also be charming as hell!

Honestly, there is so much more I could say about this subject, but I just want to leave it at: Beatle peedles, give John a break. He was a very flawed man with many serious issues raging inside him that he put out there for everyone to see… and criticize… and love.

J.R.: Come on. That’s the best response you can come up with? A tired cheap shot at Paul? I offered specific examples of the actual impact Paul has had on a political issue — vegetarianism and animal rights. And you offered … what?

No evidence at all that John’s “activism” had any practical impact.

And when you say that Lennon offered a lot of empty rhetoric, it’s also typical for his fans to accuse you of cynicism. I think that’s a handy way of deflecting the real issue — which is that John’s “peace and love” brought him lots of attention but didn’t actually achieve much in the political world.

— Drew

Craig: Well I WAS being cynical when I wrote about Yoko’s Imagine marketing and money-making machine. Guilty as charged!

But i don’t think I was being cynical about John. I think I was being factual. I wasn’t suggesting he should have kept quiet. I’m glad he spoke up. But we were talking about his impact: And I really don’t see that his efforts amounted to much practically, other than bringing him and Yoko attention. I don’t see anything he did or said that had any pragmatic outcome then or now.

I read a recent article about the Occupy movement that I think is relevant here. Basically the author was saying, “OK, Occupy, you got our attention. NOW what are you going to do? Camping in tents isn’t going to take the movement to the next level? What are you going to do NEXT? The author was basically saying that Occupy, to have a real impact, had to begin doing the sort of grassroots politics that the Tea Party did. So far, unfortunately, Occupy doesn’t appear to be taking that advice. And I think the same thing could be said of John’s activism: He got the media’s attention, and then he didn’t do anything with it.

That’s also why I was comparing John’s activism with Paul’s lifelong activism. The things Paul has gotten involved with, politically, are VERY pragmatic and not pie-in-the-sky at all. What we eat. How it gets to our table. Vegetarianism. Animal Rights. Climate Change. Anti-seal hunting. Anti-arctic drilling. He’s been very focused and specific in his activism. And maybe that’s his personality, but it’s been far more effective than John’s activism ever was.

Craig, you wrote: “Who wants the celebrities we have today who refuse to say or do anything that might possibly alienate a percentage of their designated demographic? Not me. Give me the John Lennons of the world every time.” I would agree with you — except I would also include Paul McCartney. And I would also point out that Paul HAS for years risked his popularity on behalf of issues that are unpopular with the majority. He’s helped to make vegetarianism more mainstream but the much of the world (especially the UK and US) is still dominated by meat eaters. He has gotten a ton of grief over the years about his activism, when it would have been in his interest — financially — to just keep quiet. I’m glad he spoke up. And it rankles that certain posters refuse to acknowledge the man’s decades of activism. But then it’s typical.

— Drew

Oh, this is fun–thanks so much everybody for commenting so far, and those who will comment in the future.

@CS: Totally agree that Gloria Emerson was obnoxious and condescending. But keep in mind, she’d actually BEEN to Vietnam. Vietnam wasn’t a concept to her, and I think it was John and Yoko’s conceptualizing that offended her. This from Wikipedia: “Emerson said at the time—and repeated decades later—that she believed the Beatles and Lennon ‘could have stopped the war’ had they performed for U.S. troops in Vietnam.” And if she believed that, she had every right to feel rage when she saw Lennon sitting in bed pontificating instead. Is she right, could they have stopped it? That’s an interesting question worth another post if people are interested. It will take some research on my part.

I also agree, @CS, that Lennon’s activities should be judged affectionately, and in context; and that it was extremely laudable for him to try to use his public persona to influence the world positively. At the same time as John and Yoko were staging Bed-Ins for peace, people were claiming that Charlie Manson was a political prisoner and declaring 1969 “the Year of the Fork,” because of the fork left stuck in “that pig Tate’s belly.” Strange-ass time.

IMHO, there wasn’t a thing wrong with what John and Yoko did, and there was some right with it, too. But the amount one thinks that was right with it, is precisely the amount that makes one wish it was more pragmatic. That may have been impossible; John Lennon was not a very practical person.

The damage comes from the inflation of these stunts into Stations of the Cross, which they have been since 1980. First, this behavior often have an unseemly commercial aspect, and as explained, I believe that works at cross-purposes to a message of peace. Second, this image of Lennon has spawned a generation or more of people on the Left who believe politics is largely an exercise in publicity, celebrity and symbolism. Publicity, celebrity and symbolism are involved, but they can’t be the whole enchilada.

Think about this: for all the good that John did, and all the people who loved him; and for all Yoko’s indefatigable promotion of him (and herself), we still do not have meaningful gun control in the United States. But we do have a persistent trope of celebrities adopting causes–often very sincerely–and adding a usually inconsequential, narcissistic political dimension to their fame. This ain’t progress, and I’d hope that, were John alive today, he’d agree. But he’s NOT alive, in large part because “our side” can’t muster the pragmatism necessary to turn even popular ideas like gun control into laws and institutions. We can, however, arrange for beams of light to be projected into the sky from October 9th to December 8th. That’s nice, but I think that should come AFTER the real stuff.

If you’re disappointed by John’s defensiveness in the video, what about Emerson’s rudeness? She was not just challenging him, she was straight-out attacking him

Oh, absolutely; she was not being civil, either. But I see that as the semi-righteous wrath of a person with actual involvement in the peace movement, who feels said movement is being materially compromised by some rockstar’s whim. And maybe that was an overreaction on her part, but I do think that’s what’s going on with her — especially after John’s “If it saves a life” line, where you can just feel her flip her lid internally (“Good gravy, this man actually thinks he is saving lives…”)

Whereas John’s incivility (IMO) was 100% about ego. At his first peace demonstration. To “save lives”. Ahem.

All that said, I’m totally with you on the rest of your comment; John was, overall, super awesome. And when I view his activism merely as one aspect of his changeable, brilliant, exasperating, lovable personality, then I have no complaints, only love.

But within the context of political activism itself… yeah, I have issues. And those issues are infinitely compounded when conventional wisdom waxes rhapsodic over him — OH the wisdom, and OHHH the vision, and OOOHHHH the philosophical genius. Cuz, nope. In that particular outfit, dude is the nakedest emperor that ever emped.

I’ll go a step further and say that I don’t just view Lennon’s peace years as sincere but ineffectual, or something like that—I think they are an abject embarrassment and tarnish his legacy as an artist, which is the only way in which most people beyond the relatively small number who buy into the mythology Yoko has promoted since 1980 perceive the man.

Lennon wasted vast amounts of his artistic capital on the peace movement. “Power to the People”, “Freeda People”, “Only People” and most all of the STINYC album are among the worst songs I’ve heard from any respected classic rocker, especially well into their career. They are vacuous, melodically simplistic, and uninspiring. For a man who so often had the knack of marrying the perfect musical phrase to the perfect words, Lennon often seemed to be at a complete loss to say anything surprising, meaningful, or unique in his peace numbers. And if he couldn’t communicate peace activism effectively in his music, what good was he as an activist? People, as Michael points out, were plenty aware about the Vietnam War prior to Lennon taking it up as a pet cause.

Not just that—him nailing himself to that platform may well have got him killed. Yes, MDC is insane, and yes, it’s entirely possible he would have sought Lennon out anyway. But had John not preached trite truisms that he never had any intention of practicing and stuck to singing about politics either in more detached, less sanctimonious ways (“Revolution”, for example) or confined his social comment to the type of lazy existentialism we heard from him back in 1966, it would not be nearly as easy to level charges of hypocrisy at him. Lennon made himself a target, and for what? For Yoko?

This is a great convo guys.

Drew you are right on with Macca. Whether his method was thought out ahead of time or not, Paul’s baby-steps policy of activism, slowly but surely chipping away at the food industry and increasing awareness of its horrors has seemingly been effective (though I have nothing to back this up with at the moment). In johns typical but adorable fashion he tried to solve world peace overnite (and in bed) and then seemed to forget about it soon thereafter. Good comparison, drew.

Ya know, I’m usually the last guy to defend Yoko but I like all her PR and weird stunts like the Light Tower in Finland. It keeps John in the news pretty much every week, around the globe. If it does nothing else, that makes it worth it to me.

*sidenote: did anyone see Yoko and Sean on Jimmy Fallon about 10 days ago? They were blathering on about something or another and showed a picture John had drawn at age 11 that was dated February 18. Yoko and Sean seemed to think this was particularly amazing, that it was some sort of a sign all bc that date happens to be Yokos birthday. Silly stuff. Also, Sean has longer hair now and looks EERILY similar to his father now more than ever.

Regarding John’s activist years McB says

“I think they are an abject embarrassment and tarnish his legacy as an artist”

This is kinda what I was getting at with my original question to Mike. Is this true, do we think (I know how McB feels)? I think John definitely felt he wanted to contribute more and/or be remembered for contributing more and that’s one of the reasons for his activism. Not the whole reason, but certainly some, IMO. Little did he know (or maybe he did?) that his legacy would really be: music, music, music, music, music, bed-in, music music, music.

CS:

I kinda agree with your point but we’re just trying to have a little convo here, a little back and forth. We all LOVE John probably more any other musician or ‘civilian’ for lack of a better word (besides the other 3). To me, it’s fun to think and discuss what-ifs and various other unanswerable questions.

McB writes: “Lennon wasted vast amounts of his artistic capital on the peace movement. “Power to the People”, “Freeda People”, “Only People” and most all of the STINYC album are among the worst songs I’ve heard from any respected classic rocker, especially well into their career.”

Agreed. And thanks to McB, this is the first time I’ve realized that the acronym for John’s Some Time in New York City album is STINYC — as in Stink, which it does.

Ha. 🙂 Immature, I know, but that gave me a bit of a giggle. I shall forever think of it now as John’s Stink album. Ahem. Sorry!

— Drew

Excellent points, all of you. Yes, John’s foray into the political arena may have been (not completely) ineffectual, but when you realize that his activist period only lasted about 3 years, it takes on much too great a proportion of what was to become too short a life. And while I concede that Yoko’s “indefatigable promotion of him” contributed to the John as Peace God meme, I just have never fully agreed with the notion that our man Lennon was deified after his death. If anything, I have seen too much of the Goldman mythology creep into the public perception of him.

I suppose my point is had he lived longer, we would have seen so much more from him, including, I would suspect, a political maturity… and @Drew, that would’ve included taking up many of the causes that you have attributed to Paul, who wasn’t really politically vocal until well after John passed. (And who, like John, was influenced by his wife… both Linda and Whatshername!)

@Michael, I get where you’re coming from re: “publicity, celebrity and symbolism,” but I also feel that the failure of the Left for the last 30 years goes way beyond celebrity tokenism (and I know you do, too). John hinted at it himself when he told Emerson that nobody reads the peace manifestos written by intellectuals. The Left has failed to bring its message to the common people, while… well, you know what havoc the Neocons have wreaked. (And, may I add parenthetically, that some celebrities have learned to become more intentional with their causes. George Clooney and Mark Ruffalo come to mind.)

@CMO#9, I’ve read the blog enough to know where y’all are coming from. 😉 I appreciate everyone’s candor.

@McB, John didn’t just pay creatively for his politics. He was also bugged, followed, and had to spend several years fighting to stay in the US. For what, indeed. And after ALL THAT, he’s planning to march in Japan in December of 1980.

As stated in Life After Death for Beginners, my theory is John saw the Maharishi and thought, “THAT’s a good job.” He was practically a guru anyway, and it was a place he could go that normal ol’ nice ol’ humble ol’ Paul could not. Secular gurudom was a way to be bigger than The Beatles, and that’s what John’s wounded ego wanted.

Ironically, John’s splitting away to “be his own man” was a great way for everybody manipulate him, to get a piece. To her credit, Yoko seems as committed to “peace” as John was, but the permanency of JohnandYoko was hardly guaranteed in 1969, and Yoko surely knew that the more they were publicly connected at the hip, the higher-risk it would be to drop her. Remember, John hadn’t been big on commitment (except for Mimi and his mother), but he didn’t want to look a fool to the world. “Love of your life, eh John?”

So. Psychoanalyzing someone else’s marriage. That’s a nice thing to do on a Sunday morning! But here’s why it’s germane, and this touches on @McB’s comment: secular gurus die. John knew this, even in 1968-69, and so for the rest of his life, any periods of political activity were built on a knowledge–sometimes it seems almost a hopeful expectation–of martyrdom.

That was his choice, but Yoko encouraged him to go down that road–and KEEP on that road, and that’s a peculiar act for someone who loves you. What makes it genuinely icky is how much she’s benefitted; if John hadn’t turned himself into a secular guru, Yoko would be just an interesting lady (and probably a better artist–her work basically stopped developing the moment she became mega-famous). But when John became Christ, Yoko became the Virgin Mary, and while that was a slight bump up for JL, it’s given Yoko a whole new life.

It’s OK for Yoko Ono to be a secular guru–nobody in power has ever been threatened by her. Her game is to seem daring; that’s OK, lots of contemporary artists work this ground and I like pictures of vulvas as much as the next person. But John Lennon was a genuine bellwether, immensely more popular and influential than a conceptual artist could ever be. Political action was much, much riskier for him.

These are the questions I keep coming back to: after the hell they’d gone through in the early 70s, was it the action of a loving spouse to start up the whole JohnandYoko political machine in 1980? How about wrecking their security? How about hitting the recording studio the day after her husband was shot? Or continuing to live in that building, passing by his murder scene, every day for 30 years? Would John have done any of this? Or any other Beatle spouse? Or you? It’s truly bizarre.

@McB’s right that JohnandYoko’s peace campaign was the beginning of a self-destructive behavior that would eventually cost John Lennon his life, and–especially if one judges it pragmatically it seems like a terrible, terrible waste. Whatever the provenance or backstory of MDC, in retrospect he was inevitable. Not because Lennon was megafamous (many people are) or even committed to causes (Paul and George are/were for decades), but because he was playing Yoko’s pseudo-confrontation game–but when HE did it, his fame and esteem gave the confrontation a dangerous, indeed deadly, weight.

Her haughtiness aside, Gloria Emerson understood something that John Lennon did not. His petulant unwillingness to learn it probably cost him his life.

@CS, this is super:

I suppose my point is had he lived longer, we would have seen so much more from him, including, I would suspect, a political maturity… and @Drew, that would’ve included taking up many of the causes that you have attributed to Paul, who wasn’t really politically vocal until well after John passed. (And who, like John, was influenced by his wife… both Linda and Whatshername!)

Lennon would’ve been an essential, and fascinating, political person as he aged. It’s almost too sad to think about.

Let’s not forget George as an avatar of change, either. Bangladesh was a much more effective leveraging of rock godhood for genuine good, and everybody knows what I think of meditation.

In the end, The Beatles’ cultural impact has been hugely positive–unique–and JohnandYoko’s Peace Campaign was a part of that. Whatever else it was, it was positive and optimistic, and that’s wonderful.

Regarding Paul’s activist songs…let me cite the unintentionally funny lyrics for “Looking For Changes”…at least his heart was in the right place even though the lyrics are terrible…

I saw a cat with a machine in his brain

The man who fed him said he didn’t feel any pain

I’d like to see that man take out that machine and stick it in his own brain

You know what I mean

I saw a rabbit with its eyes full of tears

The lab that owned her had been doing it for years

Why don’t we make them pay for every last eye that couldn’t cry its own tears

You know what I mean

When I tell you that we’ll all be Looking For Changes

Changes in the way we treat our fellow creatures

And we will learn how to grow

When we’re looking for changes

I saw a monkey that was learning to choke

A guy beside him gave him cigarettes to smoke

And every time the monkey started to cough

The bastard laughed his head off

Do you know what I mean?

Oh, I almost forgot another unintentionally funny McCartney protest tune…the lyrics to “Give Ireland Back To The Irish”…

Give Ireland Back To The Irish

Make Ireland Irish Today

Great Britain You Are Tremendous

And Nobody Knows Like Me

But Really What Are You Doin’

In The Land Across The Sea

Tell Me How Would You Like It

If On Your Way To Work

You Were Stopped By Irish Soldiers

Would You Lie Down Do Nothing

Would You Give In, or Go Berserk

Give Ireland Back To The Irish

Don’t Make Them Have To Take It Away

Give Ireland Back To The Irish

Make Ireland Irish Today

Great Britain And All The People

Say That All People Must Be Free

Meanwhile Back In Ireland

There’s A Man Who Looks Like Me

And He Dreams Of God And Country

And He’s Feeling Really Bad

And He’s Sitting In A Prison

Should He Lie Down Do Nothing

Should Give In Or Go Mad

Just for comparison, here’s John and Yoko’s “Luck of the Irish”:

If you had the luck of the Irish

You’d be sorry and wish you were dead

You should have the luck of the Irish

And you’d wish you was English instead!

A thousand years of torture and hunger

Drove the people away from their land

A land full of beauty and wonder

Was raped by the British brigands! Goddamn! Goddamn!

If you could keep voices like flowers

There’d be shamrock all over the world

If you could drink dreams like Irish streams

Then the world would be high as the mountain of morn

In the ‘Pool they told us the story

How the English divided the land

Of the pain, the death and the glory

And the poets of auld Eireland

If we could make chains with the morning dew

The world would be like Galway Bay

Let’s walk over rainbows like leprechauns

The world would be one big Blarney stone

Why the hell are the English there anyway?

As they kill with God on their side

Blame it all on the kids the IRA

As the bastards commit genocide! Aye! Aye! Genocide!

If you had the luck of the Irish

You’d be sorry and wish you was dead

You should have the luck of the Irish

And you’d wish you was English instead!

Yes you’d wish you was English instead!

We can agree…John and Paul were no Pete Seeger or Bob Dylan.

J.R.: You’re dodging the point again. Paul has never claimed to be a protest singer or a writer of protest songs. John DID claim to be a protest singer and he’s the one who produced the weak song that was Luck of the Irish, and the even more embarrassing Some Time in New York City album.

Give Ireland Back to the Irish is a better song in every respect than Luck of the Irish — though not by much. Both songs are weak. But given that Paul was the one living in the UK at the time he released that song, and the title itself was VERY controversial at that time, it was Paul who took the biggest risk personally and professionally in writing his protest song about Ireland. John, who was living in New York, didn’t risk anything at all.

— Drew

Drew: I call your attention to the following article:

http://www.metro.co.uk/showbiz/823399-macca-wants-to-write-protest-songs

The money quote:

“I’d love to write more protest songs, but I don’t think I have the knack for it that other people do. I’ve complained about situations – Give Ireland Back To The Irish, Big Boys Bickering – but they’re not necessarily my better songs.”

At least he’s honest about it.

And Drew, I didn’t even list Paul’s most egregious effort (in my opinion), “Freedom”—a PRO-WAR protest song!

I’ve really enjoyed reading this thread so far. This is such a complex subject that it’s hard to sort through.

I’ve never doubted that John Lennon was sincere in his peace campaign, and he deserves credit for getting out there and helping to focus people’s attention on the issue. I think he felt that with fame came responsibility, and he was trying to create an atmosphere in which positive change could happen. No discussion of how effective the campaign was should leave out of account that it was honorable of him to stand up for something he believed in strongly.

But I also agree with Michael that the “what NOW?” question is huge. OK, what do people need to DO to create this change? Unless you get down to the level of daily life and decisions, it’s all hot air. That’s why you can buy merch emblazoned with peace signs at your local Wal-Mart, Sears, etc. — “peace” as a concept is no threat to anything. I recognize that the atmosphere was different in the late 1960s/early 1970s, but the flaw was there. Talk without meaningful, concrete action just doesn’t go that far.

Drew, I agree with the comparison you make with McCartney’s vegetarianism and animal activism. (And it’s a fair point that he was influenced by Linda , as another commenter pointed out.) I don’t think McCartney’s explicitly agenda-setting songs are very good, but I do admire his dedication to what he believes in, and I respect that his activism on the subject of animal rights and vegetarianism grows out of his own daily practice.

J.R., I don’t know why you’re so hard on McCartney’s songs in comparison to Lennon’s. The fact is that both have written duds — for example, “Only People,” from “Mind Games,” is a “peace and love song” that, however well-intentioned, is flat-out terrible. We can give the laurels for writing idealistic political songs to Lennon without needing to kick McCartney in the kidneys, yes?

I think the Beatle who wrote the most convincing (to me, anyway) songs about changing your head is George. And I think “Brainwashed” is his best album in this respect — free of bitterness and saturated with the understanding that you’d better work on yourself first before you tell others what to do.

And I’m glad that this conversation has degenerated into vitriol and name-calling, as too many online ones do.

Re: my last comment, I meant “HASN’T degenerated into vitriol or name-calling,” of course. [This should teach me not to post after having only one cup of coffee in the morning.]

One of the major reasons I love this blog is that it can host forthright debate without its tipping into frenzy.

I think it was Michael who raised the issue of how John and Paul were influenced by their wives — in terms of their political activism. Here’s my 2 cents. I’m just typing off the cuff so feel free to shoot this full of holes but here goes: It seems to me that Linda was better for Paul’s activism — in the long term — than Yoko was for John’s.

First, both women played a major role in getting their husbands more politically involved. So points to both Linda and Yoko for that. And points to both men for loving strong women. Most rock stars choose models for their wives. John and Paul chose bright, ambitious career women. Which is cool.

But Yoko’s performance art, her tendency toward the conceptual, toward the theater of the absurd, and away from specific causes and issues influenced John to indulge in a lot of flighty political gestures that were at odds with his strong suit: his brains, his deep interest in the news, and his ability to be articulate about specific issues. He already was an impractical person and she encouraged his worst tendencies. In some ways, Yoko took away his edge in the political realm by pushing John toward the vague and away from the specific. As Nancy writes, John and Yoko today are now associated with “peace” as a vague concept that is no threat to anyone and doesn’t offer any answers either.

Linda, by comparison, was the female version of John politically — outspoken on the issues of animal rights and vegetarianism. She was the extremist of the McCartney family, the sort of person who really got in people’s faces on animal-rights issues (which is one reason why she wasn’t well liked while she was alive). But her outspoken, extremist approach influenced Paul to be far edgier in his activism, and far more specific in his advocacy, than he would otherwise have been. Even after her death, and after his divorce from HM (a woman even more strident about animal rights and veganism than Linda), Paul has continued his activism. Except now he’s found his own more measured style: His Meat Free Mondays campaign (a modest campaign that I can’t imagine Linda coming up with; it’s too moderate for her), or the way he has people at his concerts quietly handing out free copies of the video he narrated for PETA about the animal torture at slaughterhouses. His style is, “Here, try this, watch this, you might like it.” But would he have done any of that without Linda? I doubt it. She gave Paul his edge politically. She brought it out of him.

In short: Linda’s extremism and Paul’s moderate conciliatory style combined to better effect than did Yoko’s conceptual style and John’s outspoken yet impractical personality.

Any of this make any sense?

— Drew

I think that does make sense, @Drew. My only suggestion would be that Yoko changed John’s focus not from the specific to the vague, but from the personal to the theoretical/conceptual.

When John was writing or talking about something he’d experienced personally, he was magnetic. When he talked theory, he was extra-boring because you wanted to hear about HIM.

@JR, you’re harder on Paul than I am, but I agree that “Freedom” is distasteful. Paul pleases to a fault; John antagonized to a fault; political songs are not really their forte.

J.R. and Michael, I have to respond about “Freedom.” I don’t like this song, and I think in general McCartney’s songs decrease in quality as they become distant from the personal, but I also think this is one song that needs to be put in context.

It was written right after 9/11, remember. And not with the hindsight that the Afghanistan/Iraq wars have given us, either.

The first couple of lines, “This is my right, a right given by God /To live a free life, to live in Freedom” sound a lot like the portion of the Declaration of Independence that states “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

And even the lines “I will fight, for the right/

To live in Freedom” seem to me more realistic than strident.

I truly hate war. I wish all conflicts could be resolved without it. I think we’ve fought far too many for the wrong reasons, and have made things worse thereby. But can I be against it in all circumstances? No.

For example, I think fighting the Nazis was necessary. They weren’t going to be stopped by negotiation — that was clear. And frightening as it is to contemplate, we now have groups, the Taliban chief among them, who believe it is their God-given right to prevent women from being educated or enjoying practically any freedom, to impose their views of what is and isn’t religiously allowed on everyone in a country, and to run things as they see fit without giving citizens a recourse.

I’m far from agreeing with everything the U.S. did in response to 9/11, but the atrocity of the terrorism on that day also remains.

So, while I don’t like this song and don’t think it helped matters at the time, I can’t really fault McCartney’s sentiments in it, as I understand them. It’s worth noting that in 2006 he publicly apologized for the song and its “pro-American” sympathies, after he was criticized sharply for it.

Which brings me back around to “peace” as a commodity. Real peace requires real work. It requires acknowledging, among other things, that there are substantive differences between people and nations. Just saying you’re “for peace” isn’t enough. And I’m talking to myself as much as to anybody else here.

I keep wondering how to chime in usefully on this, but people are hitting all the sides of this issue in terrifically articulate and insightful ways.

There are a number of ways to feel about John’s and Paul’s particular forms of activism, and impossible (for me anyway) not to feel a number of them in simultaneity. John’s 1969 peace period was foolish, but on a certain level quite gutsy. Paul’s issue-engagements have been mostly safe and uncontroversial, but also consistent and practical.

As noted here, both wrote political songs that were unredeemably awful. They break even there.

John’s fuzzy-brained theoretical-conceptual-Yoko-derived approach is necessary to the degree that, as Paul Goodman, Norman O. Brown and other pre-Beatle-era avatars of social change kept insisting, change is impossible without first being able to imagine change: if he did nothing else, John drilled the importance of that into the collective-commercial mind. (To the point perhaps where, being so well aware of it, we no longer have to do anything about it.)

Many people (including me) have tapped Paul publicly for his advocacy of “soft” issues (landmines, animal rights) over “hard” (abortion rights, gay marriage). But the soft issues matter too, no matter that only psychopaths would claim to be in favor of children losing arms and legs, or of killing rabbits so that dowagers can paint their eyes purple.

These are very complex (or very simple?) guys doing what they felt was right or at least compulsively unavoidable at particular moments. Moments have a way of passing quickly, leaving the rest of us a lot wiser and the guys themselves exposed, unable to take back their choices even if they could.

In response to the specific film clip that started this off, I can deplore Gloria Emerson’s style (that heavy-lidded, cigarette-lofting “Oh, dear boy” bit), but I cringe at John’s defensiveness, self-righteousness, and self-delusion. When he tries to shout Emerson down (“IF YOU CAN SAVE LIVES–!!!!!”), what we hear is not a human being thinking but the mindless motor of ego revving hot, its noise drowning out any contradictory reality.

Devin: I agree that land mines — like peace — is a soft cause that no one would oppose (except nut jobs).

But animal rights doesn’t strike me as a soft issue at all. The majority of people in both the US and the UK love their meat and many of them get VERY hot when they’re challenged about the ethics of meat consumption or the ethics of factory farming. People also get very hot about the use of animals in medical research, which Paul has opposed but which many people — normal people, not just psychopaths — are in favor of if it saves human lives. Those are controversial issues on which thoughtful people are very much split. I’ve seen Paul get absolutely roasted in the British papers when he speaks out on vegetarian and animal-rights causes, so I would argue that his advocacy on those issues has been risky for him, career wise, and sometimes done him far more harm than good.

I can’t see Paul getting involved in abortion rights (since he’s not female) or gay rights (since he’s not gay, or so he’s said). For him to get involved in gay rights now just would look like he’s jumping on a bandwagon. Anyway, he lives mostly in Britain, and neither of those issues seem to be anywhere near as “hard” in the UK as they are in the U.S., are they?

— Drew

To me, Drew, the difference between a “soft” and “hard” issue is how likely it is to divide audiences, inspire anger, perhaps even lose an artist fans. Very few popular artists are willing to brave that territory at all, and Paul, given what we know so well of his musical and personal tendencies, is even less likely than most.

To a degree, then, it is unfair to call him on that. To another degree, it is still what it is: soft politics. I bow to your assertion that animal rights is a riskier advocacy in England than it is here; certainly in the US, the warm-and-fuzzy Paul of “Hope of Deliverance” etc. couldn’t raise a hackle in the direst conservative or corporate quarters.

(Sideline on the UK-US thing: Considering that Paul has spent much of the last forty-odd years shuttling between our two countries; that the US fan-base is almost certainly his staunchest; that he has for many years maintained a residence in New York City; and that two of his wives, including his current one, have been US citizens, I don’t think it’s unreasonable give Stateside matters equal weight when we’re specifically dealing with Paul’s responses to social issues. He has hardly been the sequestered Londoner all these years.)

I’m frankly stupefied, Drew, by your suggestion that only women can or sensibly should care about abortion rights, or that only gays have a stake in marriage quality. These are social issues that in the US touch, actually or symbolically, everything that is being contested in public life today. I don’t know if this is what you meant, but it is definitively what it sounded like.

For the record, the piece I wrote about pop-star politics (Paul and many others) appeared in 2004, long before gay marriage had the momentum it has now, when the bandwagon was still in the design stage. Perhaps if Paul were to embrace gay marriage today it would look to some like bandwagon-jumping, but that doesn’t mean it would be meaningless: some bandwagons are worth jumping on.

I found more on Paul’s various homes in this article. He’s thoroughly mid-Atlantic.

Devin, no question that everyone, male, female, gay, or straight, can and should speak out about issues that matter. But I also like the fact that McCartney’s animal rights advocacy is rooted in something he actually DOES on a daily basis — not eat meat, and not use products tested on animals.

It’s clearly something he’s passionate about and feels called to advocate for. And I’m not convinced it’s such a “soft” issue in the U.S. — depends on where you live, and who you talk to.

I don’t think McCartney is cut out to be an advocate for “hard” issues that he doesn’t feel a deep personal connection to. Lennon did feel connected to “harder” issues, but faltered when it came to working out what to do with that on a daily, practical level, IMO. I can feel for them both, God knows.

Devin: Sorry to be unclear. I’m not saying only women should “care” about abortion rights, or only gay people should “care” about gay rights. Obviously everyone should care — and does. I’m saying that, for me, when I hear celebrities/activists talk about abortion rights or gay rights, they have more credibility if they are (1) a woman whose right to an abortion is directly at issue or (2) a gay person whose rights are directly affected. I”m saying that Paul jumping on either of those issues would not have as much credibility as, say, Susan Sarandon talking about her past abortions or Elton John talking about his treatment as a gay man.

As for animal rights being a “hard” issue, i think that’s the case both here in the States and in the UK. I’ve read a lot of stories on these issues, and debates about the ethics of meat eating and about animal rights inspire as much ire in comments sections as debates about abortion or gay rights. People get amazingly ugly and amazingly defensive about eating meat, because it’s so personal.

These are not matters everyone agrees on like “peace.” In fact, people get quite emotional in the U.S. talking about hunting, about medical research that uses animals. And god forbid you suggest that meat be banned for one day a week in a school cafeteria. You get all sorts of people acting like you’ve take away their right to breathe.

I don’t think this is a “safe” issue for Paul to be involved in. Not by any stretch. And like Nancy, I respect the fact that he has a direct personal connection to this issue. He’s been a vegetarian for 30-plus years. So he has a certain credibility on the issue.

— Drew

— Drew

John’s and Paul’s activisms come so clearly out of their personalities: Paul’s desire to work within the mainstream, John’s to appear brutally truthful. We can deplore or applaud their efforts in proportion.

Paul’s animal-rights stance, as it took form in the 1990s, was initially far more anti-lab-testing than anti-meat-industry, which is where the attention has swung in the last decade or so (documentaries like “Meat Inc.”), and you’re right, Nancy, it does depend on where you are and who you talk to. For what it’s worth, I grew up in Iowa, where my family still lives, and where the cattle and meatpacking industries were suffering long before PETA came long: in other words, there wasn’t much heated reaction to anti-meat rhetoric because the industry had bigger problems to deal with. I know the situation is quite different in, for instance, Texas. (But then most things are.)

You’re also right that Paul’s issues have a home-baked appeal simply because they so clearly grow out of the things he enjoys, like horseback-riding and communing with nature. But by the same token, every pop star has had his or her career advanced by gay people. And Paul McCartney has, I would bet, paid for an abortion or two in his day. Those are issues that come directly out of matters of unique importance to pop stars. The difference between them being that, whereas even Paul’s heartland fans would not forsake him for promoting vegetarianism or supporting PETA, if he were to take up for gay marriage or reproductive rights, you can damn well bet they would.

Again, that doesn’t make Paul a quisling for elevating certain issues over others. To quote the current all-purpose cop-out: I’m just sayin’.

One other point: However much property Paul owns in the U.S., he is not an American citizen, he does not live here full time, and he does not vote here. So any comments he makes on hot-button American political issues — especially ones he doesn’t have a personal connection to — would lack credibility with the public.

Still, McCartney has made many, many public comments in support of Obama, and that has made him a regular focus of nasty attack from the Fox News/Tea party crowd. So he has, in fact, pissed off a big portion of his fan base for his loud support of Obama. So to suggest he hasn’t risked his popularity is wrong.

Lots of American celebrities own property in London, and spend a lot of time there but you never hear them commenting on British politics, either. Why? Because they’re outsiders and any comments they made would be treated by British citizens with disdain, like “What do we care what an American thinks on a British political issue?” I think Paul would be treated the same way if he got directly involved in American politics. It would be different if this was his primary place of residence, but it isn’t.

And frankly, for Paul to say he’s in support of gay rights or abortion rights — at this point in his career — wouldn’t hurt him much at all. He’s already perceived as being on the left, so those stances would not be surprising. And the circle he hangs with in LA and NY are the people for whom abortion rights and gay rights are “safe” issues.

— Drew

You all are right—I am tough on Paul even though he is my favorite Beatle. He set such a high standard for songwriting craftsmanship, experimentation, and productivity between 1965 and 1970 that only a handful of his contemporaries (Lennon, Harrison, Bacharach/David, Holland/Dozier/Holland, Stevie Wonder, and maybe Ray Davies) were even remotely in Paul’s league as a composer.

Re the video: Who is this spoiled, self-indulgent rock star? Was this the guy in the back seat of the limo who caught onto Bob Dylan trying to take the piss out of him and turned the tables on Dylan?

Was this the same guy who eviscerated a patronizing Al Capp and sent the cartoonist fuming mad from John & Yoko’s hotel room?

John must not have been himself that day, because Lennon usually ate impertinent journos as between-meal snacks.

I’m sorry I misconstrued the meaning of your comment, Drew. Thanks for clarifying it for me.

You’ve seen what you’ve seen and I’ve seen what I’ve and what we have here is a flat and simple case of dueling perceptions. My perception tells me that many British critics of American policy have been granted great credibility by US audiences (Christopher Hitchens and Andrew Sullivan come to mind). But if your perception is that Paul would be found not credible for his foreignness, I can’t tell you you’re wrong. Hitchens and Sullivan were/are certainly disdained by some–yet their words have helped shape the discourse nonetheless.

Likewise, if the evidence of your observations suggests to you that Paul has placed his popularity at significant risk by advocating vegetarianism and animal rights, who am I to contradict? All I can do is respond that my observations tell me something different.

But to clarify one thing, while certain positions (say, on gay marriage or abortion) may be safe within the bi-coastal celebrity circles, that hardly makes them safe out in the rest of America, which amounts to something like 99 percent of the population. If Paul came out in favor of gay marriage, he wouldn’t risk his popularity with the studio execs or CEOs who pay thousands for luxury boxes at his concerts. But he would, my perception tells me, risk it among the sorts of Americans who still boycott companies for being gay-positive, and vote for homophobic or misogynist politicians. But again, that is merely perception based on my observations and impressions of the current situation, and therefore not provable.

In the midst of this, I cannot but think that Paul has become so vaunted (a British paper may roast him, but he’s the one with the knighthood) that it’s likely no position he could take would dent his stature. Leaders of the world pay him obeisance. Rockers and rappers, white and black, geezers and day-schoolers alike worship the man. He is one of the untouchables of our planet. There are different kinds of credibility, but the only kind that means anything is the kind that is earned. Paul has earned the credibility of an intense and all but unprecedented celebrity that now spans nearly five decades, and runs across all nations and ages. I think–my perception is!–that Paul could say literally anything he cares to and get away with it. Disdain would roll off him like raindrops off a monument.

Except, Devin–and forgive me, my prose isn’t going to be up to your calibre, I haven’t eaten anything all day and am typing solely from limbic reactions and muscle-memory–except that Paul’s five decades of celebrity have been explicitly based on him being an nice, polite, crowd-pleasing guy. Rather than Lennon whose public persona was that of the loud-mouthed weirdo.

So Paul has to be more careful than one might expect. Even after all he’s done, most people consider him a lightweight (see that Sussudio joke earlier in the thread). Lennon was considered a serious political activist, wrongly; McCartney isn’t, wrongly. Lennon got rope the same way Andrew “Bareback” Sullivan and Christopher “Raging Drunk” Hitchens do/did. McCartney has not, and would not.

To me it comes down to sincerity: I find McCartney’s political activism to be rooted in his own life and experience, and thus have no trouble believing that it is sincere, and that he tries to practice what he preaches. I find Lennon to be the guy–very common here on the Westside of LA–who avoids his own internal pain by concentrating on “the big picture.” You know, the incredibly privileged, hyper-aggressive shithead who cloaks his rage in the language of enlightenment. The term I’ve heard for this is “spiritual bypass.” George does it when he says, “You’ll stay on the fucking label. Hare Krishna.”

No disrespect to either guy, but it’s McCartney–the supposedly insincere one–who’s lived his truth. John lived Yoko’s truth, which is that you can talk peace, freedom, and equality, while you live like royalty, enjoying all the benefits that accrue thereto. Maybe there’s more to her, but she doesn’t make it easy to see.

John and Yoko had a great belief in the ability of simple messages, repeated incessantly, to become reality. When he’s considered to be the political visionary of The Beatles, it’s difficult to argue that belief was wrong. But that’s not a positive message, at least not to me. It’s a deeply cynical, elitist and manipulative one. John Lennon was so conflicted, such a mess, that it’s hard to call him a hypocrite–I believe he truly wanted peace, and believed “Imagine” when he sang it. But if I had a kid, and I wanted him/her to emulate one person or the other–in this particular regard–I would probably pick McCartney.

“Disdain would roll off him like raindrops off a monument.”

Lovely sentence. And to a degree I think you’re right. If Paul said he was in favor of gay marriage or abortion rights, that wouldn’t affect his career much at this point. He’s rich enough that he doesn’t have to care anyway. That said, I’m not sure such pronouncements by Paul would really have that big of an impact. As Michael says, people don’t take Paul seriously enough as a political activist — and they took John way too seriously, which put a lot of pressure on Lennon.

All of which makes me wonder how John would be perceived today if he was speaking out on issues. Because the challenge for celebrity activists today is that there is a huge backlash against the very concept of a celebrity activist. It’s the “shut up and sing” phenomenon.

As I said, I read a lot of American and British newspaper sites (just because I’m a news junkie). And celebrity activists like Bono and Sting are regularly pilloried. People are just savage about them and love to call them hypocrites (Bono for urging people to give to Africa yet moving his own money out of the financially depressed Ireland to avoid its high taxes; and Sting for lobbying on behalf of the rain forest and yet jetting around the planet leaving a huge carbon footprint). I constantly see “shut up and sing” comments about them, and worse.

I think John — the fabulously wealthy man who sang about imagining no possessions yet had loads of them, the man who sang about peace and yet wasn’t all that peaceful in his personal life — would be at risk of getting exactly the sort of disdain and hatred that Sting and Bono seem to inspire these days.

McCartney gets attacked too, (especially from the meat-eating crowd and, here in the U.S., from the anti-Obama crowd) but because Paul’s approach is more congenial and less confrontational, and because he tries to practice what he preaches about vegetarianism, Paul seems less of a target. And he probably also benefits from being taken less seriously, as Michael smartly pointed out, than Lennon was. So the reaction to Paul is often “Silly left-wing hippie smoked too much and fried his brain.” Somehow I have a feeling the reaction to John’s activism in our times would be far more vicious.

Thanks all. This has been a really thought-provoking discussion.

— Drew

Michael, you said better than I could pretty much what I was thinking about Lennon’s and McCartney’s respective forms of activism.

J.R., I think Lennon’s defensiveness in this encounter with Emerson is telling. He can’t simply dismiss her, as he did with some other journalists, and I think that’s because she’s touched on something he suspects himself. Lennon was too smart not to wonder if his and Yoko’s peace campaigning was making a real difference. Part of Lennon’s reaction is certainly due to Emerson’s “dear boy” attitude, but more of it, I think, was due to her having raised questions he had to have himself, however he might suppress them.

About being hard on McCartney because he was so great in the 1960s: I’ve said before that I don’t think any of the former Beatles achieved separately the same level of greatness they had together. And that’s too much to expect, really. At one level it makes sense to be extra harsh on a musician because you think he’s capable of better things, but at another this attitude is one of the main things that drove Lennon in particular crazy about fans. What the Beatles achieved together often became a flail for people to smack them with, once they were pursuing solo careers. Having people love a particular body of work and period of your life that isn’t reproducible, and measuring everything you do against that and finding it wanting, had to be a literal drag on them all.

@Drew, the interesting question to me is: to what degree can John and Yoko–being the pioneers–be faulted for creating this fundamentally flawed template of celeb activism? ‘Cause they weren’t wrong–stars can motivate fans to behave differently. And the pushback doesn’t usually come from fans disagreeing, but implicitly or explicitly resenting the elitism and hypocrisy embedded (ha!) in John and Yoko-style activism. Two things you really couldn’t call John Lennon before Yoko was elitist or hypocrite.

I don’t think people’s “shut up and sing” reaction is just meanness on their part (though that’s some of it). As my friend who works in progressive politics jokes, “Not only are we celebrities richer and more successful than you, and have more sex, we’re also better people.”

If a celeb is going to start suggesting behavior, he/she had better reflect behavior themselves. So Bono pays 98% tax on all monies earned in FY2012–what the hell does THAT guy need with more money? I mean, really…if he’s not getting it taxed, he should be giving every penny of it away. He’s a devout Catholic; does he not believe Jesus about the rich? Or does he engage in all sorts of petty rationalizations like we all do? If he gave every year’s money away from now until he died, people would revere him–but reverence doesn’t come cheap. You can’t buy it wholesale.

Activism cannot simply be another form of conspicuous consumption, sincere but unthoughtful. And any celeb who engages in public activism can, and should, be held to a personal standard as lofty as his/her commitment. Not because it’s convenient for the celeb, or always fair, but because reverence costs more than fame, and respect must be paid to the cause and to the fans.

Whenever John and Yoko use the word “artist,” just substitute “king/queen.” It’s more accurate, and THAT’s why their political activism didn’t work. Whether they wanted it to, or what “working” even means in such a conceptualized framework, is another story.

Re: Paul’s ever-emulable and praiseworthy pragmatic and practical approach to politics. Here’s a line from his HuffPo blog entry today: “My name will be among at least 2 million that Greenpeace is taking to the pole and planting on the seabed 4 kilometers beneath the ice.” I dunno… sounds a little like acorns for peace to me. 😉

LOL! Touche, @CS, Touche.

Thought-provoking post and debate. I disagree, however. Lennon was right then and his message is still right now.

In my opinion, his intention was to cut through the minutiae and obfuscation of the debates on specific conflicts or Cold War politics and say ‘I am for peace’. Because he realised as a popular artist that simplicity is the most effective vehicle of the message.

He’s frustrated because Emerson doesn’t get it, or won’t see it. To John, she represents the bourgeois mistrust of simplicity, and the patronising, elitist dismissal akin to ‘Oh, it’s much more complex, you wouldn’t understand, dear boy’ is exactly the kind of attitude he was trying to cut through.

But John was trying to promote a message for everyone, saying it’s OK, you can stand for peace without having any esoteric knowledge of the political situation or the philosophical arguments; you don’t have to be for this movement or against that movement – you can just stand for peace.

Of course, he wasn’t alone in doing this. But I believe more people were empowered to express anti-war message through this simplicity, and have been since.

I think many other people in the public eye have been inspired by this simplicity, too – not least Paul McCartney.

I don’t think John was as naive as some people think. But he realised that ‘give peace a chance’ and ‘war is over if you want it’ were simple messages that had a better chance of getting through to people than a wordy, well-argued and articulated pamphlet.

Of course, it’s difficult to quantify the effect they had, but they undoubtedly did have some kind of positive effect. And in the circumstances I’d agree with Lennon that it was the most effective thing he could do.

Emerson’s concern seems to be Lennon’s credibility as either an artist or campaigner, or both. I’d argue that, through all the vicissitudes of the following years, both remain intact. Which is why I believe Lennon has been proved right.

@Peter, that is a SUPER comment. Sometimes I think you’re right, but then I think this: replace the word “peace” with “motherhood.” What does it mean, being “for motherhood”? If you asked 100 random people if they were “for motherhood,” You’d get 95 yeses. Moms are great.

But what does it mean for your behavior? That woman you cut off on the way to work, she’s a Mom. So’s the one who you’re fighting for a promotion. Sarah Palin’s a Mom–if you’re “for motherhood,” does that mean you vote for her because she’s a Mom, or against her because her policies would be anti-Mom? Do people “for motherhood” support or oppose Planned Parenthood? How about the right for women to see combat in the military? Being “for motherhood” makes you feel good, but it doesn’t give you any ground-level guidance on how to create a better world.

Are people “for peace” for or against a strong military? How about the UN? Do they pay their taxes, or not? Do they buy Lennon records, knowing that some portion of that money will go to Biafra?

I totally get what you’re saying about the bourgeois prejudice against simplicity, and I think there’s some validity to it. But John’s message was so simple, it was impossible to know how to apply that message, especially in the face of opposition.

The other thing–and I think this was definitely something Lennon did NOT understand–is that everybody’s “for peace,” just on different terms. Nixon and Ho Chi Minh were both for peace–providing certain conditions were met first. Ignoring the reality of conditions is a type of magical thinking.

And of course even John and Yoko ran into this problem. The very same period of the Bed-Ins, they were fighting savagely with people. “But John, shouldn’t you let Lee Eastman manage the group, just in the interest of peace?” “But Eastman’s a pig, he’s Paul’s boy! And besides, it’s MY MONEY!” That feeling right there is what war’s about.