- Needed: Paid Research Assistant(s) for a Beatle Project - October 28, 2023

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

Just got back from watching Monty Python Live (Mostly), the filmed record of the Python reunion concerts performed at London’s O2 Theatre last month. It was — and I say this as someone who bought the expensive tickets primarily out of affection — a ball, a delight; if you can see it, go see it. The two and a half hours flew by; I laughed a lot, and even got a little choked up there at the end. I’m so glad I’ve lived at the same time as Monty Python. (A shaky fan video of their farewell — “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life”— is below.)

It wasn’t Python in concert — for that see Hollywood Bowl; nor was it even Python Original Recipe. Graham Chapman is long dead, and his partner Cleese seems to be in definite ill-health. Unable to generate the physical, coruscating rage that’s at the heart of his comedy his vein-straining Olympian wrathfulness has been reduced to an old man’s prickly reserve. In the show I saw, Cleese’s place at the front of the sled was filled by Palin and Idle pulling in tandem, which gave the proceedings an avuncular, winsome, showbizzy flavor. Whereas classic Python was an assault — one using pleasure, but an attack none the less — this night was commemoration of a victory.

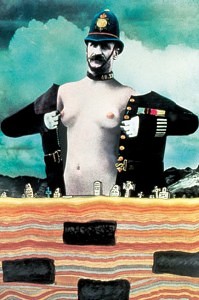

Python, before.

And yet, to my very great surprise, it was undeniably Monty Python — think the Threetles if Ringo had died instead of John. What’s more, it felt precious. In all the years since Python “joined the choir invisible” nothing in comedy has come close. Nothing has approached Python for pure intellectual intensity and amplitude, nor had its mixture of intense silliness and intense erudition, crudity and subtlety, cruelty and affection, Englishness and universality, righteous anger and fundamental optimism. Plus cartoons, and great songs. Monty Python was sui generis, and this is cause for sadness and celebration in equal measure.

U and Non-U

Like the Beatles, Monty Python was a reaction to the end of the British Empire, and what you did with that pressure was determined primarily by your social class. The Beatles group was the product of working class genius, Python upper class. Now, I’m an American, which means I can’t tease apart the infinite nuances of the British class system; they all seem exotic to me. But in this post that’s not a big deal, because one of the most important things about the Beatles and the Pythons was their mid-Atlantic flavor. In my book — and my experience — going to an upper class university gives you upper class values, so I’m using Nancy Mitford’s “U and non-U” distinction from the 1950s. But don’t get hung up on it: the difference I’m talking about can be seen easily. Though raised in similar economic circumstances and with similar gifts, Dudley Moore and Paul McCartney pursued utterly different paths to stardom. Dudley’s U, Paul’s non-U; it’s a convenient shorthand.

The Beatles, along with their non-U cohort (David Bailey, David Hockney, Michael Caine, etc.) experienced Britain’s Imperial decay primarily positively, as an increase of mobility and access and acceptance. Put Paul in a room full of peers and — well, there are probably lots of places he can get into that they can’t.

Chapman’s Colonel is funny because he doesn’t realize WWI or II happened. He’s Edwardian.

Python and its ilk, on the other hand, experienced it as a loss. The absurdity at the core of Monty Python comes from being trained to run an empire that no longer exists. That’s why Python could transpose its humor to ancient Rome and medieval Britain so easily; they were born into — or had been schooled to serve— a rigid, stable society. The phenomenon of Oxbridge comedy, its transformation from toffs in drag to an international style of humor, is an expression of cultural anxiety, where the English upper classes suddenly don’t know what to do with themselves, and everybody else is scared and excited at the prospect. (We’re getting a little of this now in American comedy, but that’s a different post.)

Their U-ness put a cap on Python’s appeal while at the same time making it catnip for a certain type of American: the troupe conquered America via PBS — roll that around in your head for a bit. Not for nothing are the Pythons the official comedy of students, and while the postwar opening up of higher ed made them a much broader phenomenon than they would’ve been (compare Beyond the Fringe ten years earlier) they are still Nutella to the Beatles Hershey bar.

The U/non-U distinction even holds up within the group: of the six, it’s the working class Idle who’s made the most money and carried the Python brand into the 21st Century. Cleese, the patrician leader, conquered the ground — television with Fawlty Towers, movies with A Fish Called Wanda — then did the very patrician thing of declaring victory by leaving the battlefield. The Pythons’ other authority figure, Graham Chapman, did the only thing that’s even more patrician than that: he devoted himself to pleasure and died young.

This class-driven desire to conquer by quitting is, in part, what caused John Lennon to take his late Seventies hiatus. The most class-conscious of the Beatles, researching his family tree and married to someone he made sure you knew was a Japanese aristocrat, Lennon knew that the most U thing he could do was stop. In fact, the most reliable indicator of class aspiration in these people seems to be, did they keep working? Dudley Moore did, Peter Cook didn’t; Peter Sellers did, and so did Spike Milligan; Eric Idle did, John Cleese didn’t. Paul and Ringo did, George didn’t. Terry Jones and Jonathan Miller split the difference, parleying financial security into the unabashed pursuit of eccentric personal interests. Making witty, incredibly erudite documentaries about medieval toilets or atheism is the modern equivalent of collecting bird’s eggs. (Needless to say, I adore this type of thing.)

Unlike the Beatles, the Pythons are not modern men, comfortable in the modern world. They are Edwardians. Terry Gilliam realized this, and it’s why the graphic look he provided for the group works so well. Their discomfort, their sense of what had been lost, and the doom surely ahead, is why they picked popular comedy, a fundamentally conservative art, rather than popular music, a fundamentally forward-looking one.

My Favorite Uncles

Watching Monty Python Live (Mostly) was like spending some time with your favorite uncles. No, they’re not who they were 30 years ago, but you’re not either. Seeing them makes you realize that time is passing. It was a melancholy thing to hear Cleese’s voice straining for air; where he used to bristle with electric anger, he now just quivers. The timing of a lot of it was off, because they were all a beat too slow — slow of mind, slow of foot. Father Time is the one audience you can’t charm.

But it was wonderful to be with them again. The flubs and softness made me appreciate how great they all were, as writers but especially as performers, at the height of their powers. It didn’t diminish what they’d done, and it certainly didn’t change my relationship to the original work. What a pleasure, a goddamn untrammeled start-to-finish pleasure it’s been to be alive when they were around.

That’s exactly how I feel about the Beatles, too. And that feeling of pleasure — of gratitude — is much too large to be affected by a mere reunion. The body of work is there. Quibbling over a reunion is like finding a misplaced dimple on the ass of Michelangelo’s David and calling the whole thing a failure. This Python reunion — in how it felt, how it made fans feel, how it connected in with the work done before — is a great predictor of how a Beatle reunion might have felt.

Monty Python sex: Edwardian, gender-bending, colorful, titillating, harmless.

There was a gentleness to the experience, an innocence. (That struck me over and over last night, how smutty the Pythons were, and how innocent it all seemed. My guess is that came from Chapman, both polymorphously perverse and a doctor, nonjudgmental about the body.) The Pythons seemed much more approachable, more human than ever before, and that was a nice thing. To create their body of work, they had to be savage to each other, and remote to us. They were calculating, driven, single-minded. Cleese in the 60s and 70s was not a pleasant man, just as the Beatles in full-flood were famously “the biggest bastards on Earth.”

But in preparing this Greatest Hits, the Pythons revealed themselves to be one of us; that is, fans. Enough time had passed that the intergroup rancor, that chemical clashing of personalities that made the Pythons (and the Beatles) shoot up like a rocket, had cooled sufficient for them to rest. And look back, and see what we have seen since 1969, that rarest of things, a group of genius. Last night the Pythons were finally free to revel in the beauty of their work, as we always have. We were finally sharing the same experience with them, and that’s something only a reunion — a mutual revisiting of something beloved, but finished — can do.

Why a Python Reunion was Important

And this brings me to the only real sadness I felt during the evening. (Well, this isn’t exactly true — I was sad not to see Neil Innes, who contributed so much. He’s currently fighting with Idle, as people periodically seem to.) The Pythons stopped working together after “Meaning of Life,” in 1983. Chapman, who was clearly more important to the group than all of us outsiders knew, died in 1989. After that, the individual Pythons were determined to go their separate ways. Like the Beatles — or Harrison and Lennon at least — breaking up seemed to be a great idea. And like the Beatles, it turned out not to be, and while I can’t blame them for pushing their luck, I do mourn the work we lost. (Apparently Idle had an idea for a sequel to Holy Grail, which was nixed in 1998. That same pushing quality that got this Python reunion to happen, was bound to be anathema to Cleese until the very, very end. Giving the fans what they want smacks of needing the fans, and that’s very non-U.)

Though I’m a fan of witty documentaries and travelogues as much as the next guy, enjoyed A Fish Called Wanda and adore Terry Gilliam’s films, and like the idea of Spamalot! so much I braved an old-fashioned Chicago blizzard to see it in previews, nothing Cleese, Chapman, Palin, Jones, Idle or Gilliam ever did has achieved the same sublimity as their work as Pythons. Yes, Brazil is great — it’s the Pythons’ “All Things Must Pass,” a big sprawling statement by the Quiet Python. And yes, Fawlty Towers deserves its acclaim — it’s “Plastic Ono Band” and “Imagine” all rolled into one. But these things are not generational touchstones like Python is. Millions will not gather in 2021 to watch a reunion of Fawlty Towers. Nothing has been as enjoyed, nothing has been as innovative, nothing has made as deep a mark on world culture.

I understand the considerable pains of group endeavor, and God knows the Pythons had earned a break. But last night reminded us all of what they created as a team, and it was hard not to consider their desire to go it alone a kind of robbery. Or at least an example of the artist being the last person to know what’s most valuable about his/her own work. And the work wasn’t theirs anyway; like all the best work, we took it from them and made it ours. That’s what reunions recognize, and formalize, and why they’re important.

A Future Predicted Out of Fear

The Beatles lasted 13 years, the Pythons 14. They succumbed to entirely predictable factors: fatigue, ego, shifting life situations. And post-breakup, both groups resented the relentless fan-pressure to reform, even going so far as to employ similar stock answers to the question. This resentment caused them to cast the demise as inevitable, but this is simply making the best of a bad lot. The Beatles did this constantly, Lennon especially — probably because he knew better than anyone that it hadn’t been inevitable, but a terrible fuck-up he regretted as he got older and truly recognized what inevitability really is. This life isn’t so filled with great art and happy circumstance that one’s “lucky break” should be broken in two just because a collaborator is driving you crazy. Lennon dropped Paul in favor of Yoko, until he dropped Yoko. Cleese’s leaving the Pythons was one in a string of divorces, none of which has provided him with whatever he’s looking for. It’s a conceit of youth to bond and split and bond and split; it’s the wisdom of age to realize that wherever you go, you bring your problems with you.

Funny? Yes. Likely? No.

I have little patience for depressive types who profess gladness that the Beatles never “tarnished their legacy” by reforming, complete with Shipperian fantasies that the Fabs would’ve been upstaged by flavors of the month like Peter Frampton. This is a triumph of fear over imagination — a stunning lack of faith in a world that produced the Beatles and the Pythons in the first place. It’s a fan’s attitude, not a creator’s. Last night’s show demonstrated that legacies are not so delicate, and too much of a good thing is, in Mae West’s phrase, wonderful.

Were a post-1970 Beatles or a post-1983 Pythons doomed to decay into irrelevance or worse? I don’t think so. First, they had taste, and that’s accretive. Time enhances it, it doesn’t go away. Separately they might have produced the occasional “Sometime in New York City” or Nuns on the Run, but together they never did. Together, they had a process, and it was that maddening, irreproducible, immaculate process that created the music and comedy that they will be remembered for.

The second point is that they shaped their times as much as were shaped by them. This is what the depressive fans are most afraid of — they cannot face the fact that the absence of the Beatles and the absence of the Pythons actually made a difference. It wasn’t the numbers on the calendar that made Seventies rock worse than its Sixties counterpart, less ambitious, less epochal, less satisfying. It was the entire creative ecosystem of the art, and the absence of the Beatles after 1970 (both as competition and via their own music) made that ecosystem a place that produced worse music. Ditto with the Pythons and comedy. With all due respect to every interview John Lennon ever gave, t’s not “living in the past” to compare eras, and find one wanting; it’s simply not falling for the conceit that new is automatically better. That’s marketing, not life, and it came in interviews that were all about selling John’s new, decidedly inferior product.

British comedy’s golden age ended when the Pythons disbanded, and a movement that had transformed English-speaking culture receded to its usual parochiality. Alexei Sayle and the whole Comic Strip crew were a phenomenon which more or less stopped at the water’s edge, just as Alec Guinness and Ealing comedies had, thirty years before. Fine comedy, but fine British comedy. When Rik Mayall died, I watched the clip floating around YouTube, and saw standup only notable because it was happening on a British stage.

Python, after.

Beginning with Beyond the Fringe and ending with Python, British comedy was the lingua franca of every smart kid in the English-speaking world; to some degree, it still is. This bond was so intense, so personally felt, that 45 years after Python emerged, a group of Angelenos gathered on a random Wednesday night to watch a bunch of old men stumble amiably through sketches we all knew by heart. (On Friday, it will happen again, at another theater in the neighborhood.) These people on the screen were no longer geniuses of comedy, performance or anything else — they were favorite Uncles, ones you hadn’t seen in years, spending an evening with you. Except that, unlike life, you know in advance it’s the last evening you’ll ever have. That made it all inexpressibly happy, and sad too, but most of all, precious.

So what would it have been like, had the Beatles all survived a few more decades of finding themselves and feuding with each other, then reunited? It would’ve been effing great. Would they have succumbed to faddishness? Would they have tarnished their legacy? No — these are futures imagined by fearful people, not Beatles or Pythons. Reunions acknowledge that the work is inviolate, untouchable, something safe enough to play with. In reuniting, they formally hand the work over to our care, where in truth it has always been. That is how you know it is work of genius, that it will last.

[In case you haven’t seen this promo with Mick Jagger, do yourself a favor and click…]

You said a lot of things about Monty Python that I’ve felt but not managed to articulate, Mike — thanks. I happened upon “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” as a 12-year-old and loved it. Enough can hardly be said about the importance of the group and their influence on later television sketch comedy (early SNL, SCTV, etc.).

Also: “Giving the fans what they want smacks of needing the fans, and that’s very non-U.” I think that’s the essential difference between Lennon and McCartney in the post-Beatles years, and the reason Paul just keeps going, and especially performing live. He loves being a showman, and that’s very non-U.

I’m glad, @Nancy.

What’s interesting about the early SNL is how different it is from Monty Python; but this is entirely predictable once one digs into it. Early SNL comes from a very different, then-new (somewhat opposed) American improvisational/standup tradition valuing emotionality and immediacy, whereas Python is deeply embedded in the old “smoker”/sketch tradition which emphasizes polished performance and construction. This is why Python’s aged better than SNL has, and became more of a touchstone for the generations that followed. The original SNL ends in 1980 and doesn’t come back. Things like Spinal Tap and Chris Guest are a fascinating mix of these opposing traditions, and can occasionally produce the looseness and naturalness of improv with the tight construction and better performances of sketch. But that’s only in the hands of the top, top people.

These days, comedy writers are thoroughly versed in the improvisational method of sketch writing and character creation, not the other — and IMHO their material feels too loose and their jokes too exclusively aimed at topics that make improv audiences laugh (sex, embarrassment, etc). “The Philosopher Song” doesn’t happen via improv; you gotta WRITE it, and then you gotta be a good enough performer to put it across, and not give a shit if the drunks don’t get it. As ever, business concerns are behind it all, pushing the improv style and discouraging classic sketch. I don’t think we’ll see anything like Python again soon; that’s not how comedy is made anymore, here or in the UK.

I think Lennon was, at heart, a snob (thanks Mimi); I’ve never gotten that sense from Paul.

Good point about the differences between Python and early SNL, Mike. I was thinking more about the “Now — this” absurdist aspect of Python, which is one thing early SNL picked up and ran with. (Sometimes right over a cliff.) From a marketing standpoint, I think Python’s success probably helped make a sketch comedy show sound feasible, especially if it was marketed as edgy (“The Not Ready For Prime Time Players”). But it’s certainly true that not as much of SNL has aged well, often because of the loose, improvisational bias you mention. They’re also often the champs of not knowing how to end a sketch while they’re ahead.

@Nancy, not to argue, but this is a topic that I once did a lot of reading on, and my current business partner was an SNL writer during those early days.

While early SNL was more absurdist than it has been since 1985 or so, it still wasn’t primarily absurdist. It was primarily topical and satirical. The guest host was usually someone current; the commercial parodies were current; there was Weekend Update, etc. Early SNL was full of drug humor, because it was topical, and dropped it later when it wasn’t topical; Python never went there. SNL came out of the post-Chicago counterculture, whereas Python came out of BBC children’s programming. SCTV was much more Python-esque in its absurdity, and its obsession with the TV form. SNL was conceived as a weekly Second City style satirical revue, and that’s pretty much what it was — with commercials and films and the guest host to hedge its bets and give it shape. Compare Weekend Update to the Python news anchors, and you’ll see the difference clearly: the former is straight topical humor, the latter uses the format to deliver all sorts of weird linking jokes, or set up sketches.

If you go back and watch, you’ll see that SNL did not do, and does not do, the main structural thing that Monty Python developed, which was avoid the chronic problem of sketches (a tendency to peter out) by ending them abruptly, or breaking their integrity (“the Colonel” comes in saying, “Stop that, stop that!”). They might want to, but filming it live means they really can’t, for production reasons. SNL sketches were and are much more conventional, which is why they go…on…forever. To avoid this, you have to be a real master of sketch, like Peter Cook. Good sketch is drama; typical sketch is improv.

To see something that’s really Python-esque, and how different that texture is from SNL and the stuff it influenced, look at this sketch:

http://youtu.be/cMjnVf0FjAI

Python-style humor is conceptual — it’s a chat show starring a guest who can’t say the letter b. SNL humor is much harder, blunter, physical/visceral rather than verbal/intellectual: a chat show starring a guest who’s selling appallingly dangerous toys to children.

Interestingly, Python was not the driver for SNL’s being developed; it was largely unknown in the US at that time (“And Now for Something Completely Different”, an attempt to repackage Python material for the American college market, had been unsuccessful). Bowdlerized episodes were being shown on ABC late at night in the fall of ’75, but they weren’t popular. The driver for SNL was the success of the National Lampoon magazine, Radio Hour, and stage show; and most of that original cast (and its head writer) came from Lampoon.

The Lampoon crew was philosophically opposed to Python-style humor, and the two groups mixed like oil and water. My friend Brian mentioned that when they first had Palin (or Idle?) on the show, he bombed. And Idle supposedly said that he considered only one SNL cast member to be worthy of being in Python which was… Dan Ackroyd. (This isn’t so surprising; Ackroyd’s sketch ideas were the most absurdist.) In researching this response, I found that Peter Cook and Dudley Moore hosted in early ’76, eight months before Idle came on — and this makes perfect sense, because of the SNL/Python rivalry (which Cook/Moore were not part of) and because they — unlike the Pythons — wrote sketches that could be easily produced in the SNL format.

All of this makes “The Rutles” even more of a miracle, and is another testament to the Beatles’ peculiar magic.

It’s much more accurate to call Python and SNL contemporaneous here in the States, with “Holy Grail” breaking Python through.

Mike, If you ever teach a class on the history of televised comedy, I am signing up! This is a subject about which I know little.

I can now see more clearly what you’re saying about the differences between SNL and Python. As a kid watching early SNL, I responded to (and therefore remember) the absurdist bits, like the Land Shark, Belushi’s “Samurai _____,” and Radner’s Roseanne Roseannadanna.

Also: Python is brainier, and you can’t get some of it without a sufficient range of cultural reference (including “high” culture). I can’t imagine anyone else doing “The Wide World of Novel Writing” or “The Semaphore Version of Wuthering Heights.”

[Whenever I watch that last, I can’t help mentally subbing in “John! Yoko! John! Yoko!”]

Aw, thanks, @Nancy. I see what you mean now.

Python is so much brainier; it’s really a niche taste that somehow broke big, whereas SNL was conceived as, and has certainly always been, something with wide appeal. “Landshark” for example, began as a MAD magazine-style parody of Jaws. Python did do this kind of thing (the Peckinpah/”Straw Dogs” reference in “Salad Days“) but the intent, and the approach, is totally different.

If you were a bright working-class British kid in the 50s, you either accepted your place in the class system (Ringo), rejected it by replacing it with another system like socialism or religion (George), tried to climb the social ladder and fit in with your ‘superiors’ (Paul), or convinced yourself that you were really one of them (John).

That’s a superb comment, @dan.

My instinct is that this set of reactions is the same everywhere, always. What do you think?

You could say the same of black music of the 50s and 60s.

accepted your place in the class system – r&b

rejected it by replacing it with another system like socialism or religion – soul/gospel

tried to climb the social ladder and fit in with your ‘superiors’ – Sammy Davis Jr/Nat King Cole type showbiz

convinced yourself that you were really one of them – Motown

Jem Roberts published a book in late 2000, Fab Fools, that situates the Beatles in the British comedy tradition and looks at them through the prism of their comedic influences rather than their musical influences. It’s a unique view of the band; every other page or so I’d go, “I’d never thought of it, but now that you mention it…” The book also spends some time on Python, the Bonzo Dogs, and the Rutles which, as Harrison said, are all “part of the soup.”

I have mixed feelings about the 2014 reunion show. I don’t fault the troupe for doing them; they had to pay off their legal fees from the Spamalot royalties case Holy Grail producer Mark Forstater brought against them. But I felt the essential anarchy of Python was missing. It wasn’t transgressive enough, playing instead the old, familiar hits. It was a bit like The Simpsons‘ joke about “Star Trek XII: So Very Tired” — “Again, with the Pythons,” a tired and weary Captain Kirk says into the intercom.

Personally, for me the last good Python reunion was The Concert for George. It was part of something else so it wasn’t about them, and the bit they did (“The Lumberjack Song,” “Sit On My Face”) felt appropriately anarchic set between the two respectful tributes to George while, at the same time, because George was a funny man and loved the Pythons as he did, it was probably the most respectful part of the concert insofar as George was concerned and certainly the part George would have loved the most. (I like to think that George was one of the Mounties on the night Python’s Live at City Center album was recorded, though I’m not sure if anyone actually knows which night that was recorded.) I also like that Neil Innes was able to be a part of it, that his relationship with Eric was okay enough at the time for him to be there, before things got bad again between them a few years later.

I know, I know, I’m a weird person. I come off like a Python grumpypuss, but I’m also the kind of person who has conversations about whether or not Michael Palin or David Bowie was better at Pontius Pilate, which is exactly the kind of weird thing a Python fan probably should have conversations about. 🙂

Oh I’m so mad someone already wrote that book! Actually I’m glad someone did, because I’m clearly never going to have time to write it, but British comedy is a very, very useful lens through which to view The Beatles’ story. For example, the cultural opening that The Beatles stormed through and widened immensely could reasonably be said to begin at the opening of Beyond the Fringe in August 1960. (Yes, there were factors underlying the cultural changes, like the rise of art schools and the ending of National Service, but if you’re simply looking at British pop culture, stuff like the “Angry Young Men” don’t feel very Beatle-like, while BTF absolutely does.) And the Goons before that.

The Beatles were, as a group, considerably funny — in a way that say, the Stones, simply aren’t. I think this comes from their always-ironic take on their own stardom and the fans’ reaction to them, and their ability to incorporate almost anything into the act. The moment anything artistic opens widely enough, it becomes comedy-adjacent.

Much of the cultural heat that settled in rock and roll in the 1960s moved into comedy in the 1970s, and that was on both sides of the Atlantic.

On the subject of comedy, I made this comment a few years ago. It’s still something I wonder about:

@Sam, that’s a great comment. When I watch the 1960s British comedians’ ethnic humor, I remember that they often cut their teeth performing for soldiers as part of NAAFI.

I think the “exotic but not entirely unknown” aspect of Indian culture was central to its appeal for George. Just as, say, blues music was to Brian Jones, or folk to the Minnesotan Robert Zimmerman.

@Sam, I remember reading somewhere (can’t remember where) that George always needed someone to look up to, and to follow. (Rather a strange trait, as simultaneously, he was very independent and singular-minded). And when he was no longer getting what he needed from John and Paul, he searched elsewhere and became a student of Ravi Shankar, and immersed himself in all things India. One thing about George, he did not do things by halves.

I love your bagpipe comment!