- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Just a quickie, ’cause I have a book to write and magazine to launch dammit–

Last Sunday, Chris Carter’s excellent “Breakfast with the Beatles” played a complete song potentially recorded by The Beatles during the Hard Day’s Night sessions in 1964.

A loving recreation of anonymous Invasion pop, we’ve only heard a snippet of this before…at 4.01 in the video below:

I looked for a full recording online, and it’s not up anywhere (yet). Is it The Beatles? Carter believes so, and I agree; it’s highly unlikely that any backing group would’ve been able to keep mum for 50 years. Furthermore, why would United Artists pay extra–even a little bit extra–for incidental music when it had The Beatles in the studio?

I’ll put up the complete track when it surfaces; anybody who finds it, put it up in the comments.

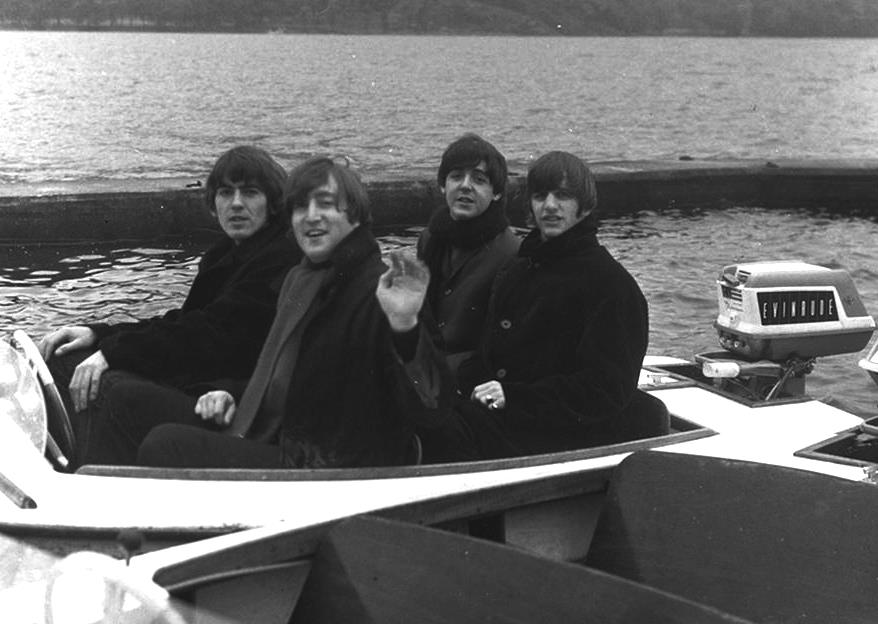

Patron Saints of Smart Kids

While we’re here, I’ll just say: I’ve always loved this scene. It conveys something basic and truthful about the way smart kids function with a certain kind of unfair adult authority — how they rebel, for real, but retreat into playfulness, mockery, and parody when outright pugnacity doesn’t work. Yes, it’s fantasy, but it’s thrilling.

Points like this require Devin or Nancy, not me, but some of the power of the early Beatles was how they were essentially empowered kids. This youthful manner is often why people who should know better call them “a boy band” — but this demonstrates precisely how they weren’t. In 1964, John Lennon was a smart, funny, fully fledged 24-year-old taking no shit from anyone, which is why I liked him so much at 12. He didn’t act like a kid, but how every smart kid wanted to act. At 12 or 16, I didn’t want my heroes to be “just like me”; I wanted them to be what I could be. And Lennon wasn’t (as much as he sometimes wished he was) a thug or a nihilist, but an intellectual inhabiting a style that was fundamentally an artistic choice. This nuanced stance of self-creation rings true to every smart teenager, and if whether you like The Beatles or a contemporary group usually comes down to your ability to shrug off the alien contexts of an earlier time.

The Beatles of the mania weren’t kids, that’s key. But kids recognized and claimed them, and that’s key, too. I think because they had all been friends since they were teens, their manner was still essentially that of schoolchums; it’s high school, not adulthood, that creates “a four-headed monster.” This vision of adolescent solidarity in the face of a fucked-up adult world — along with the music of course — is why The Beatles have made the jump generation after generation, and will likely continue to do so for a long time to come.

You can get a download of the entire show here: http://beatlesradioshows.tumblr.com/post/89843173645/breakfast-with-the-beatles-chris-carter-klos And here is the playlist so you can estimate where to find it: http://www.breakfastwiththebeatles.com/playlist/bwtbjun222014.pdf

Thanks, @Parlance!

Before I do this, lemme see if I can get in touch with Chris C and ask if there’s something he prefers.