- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

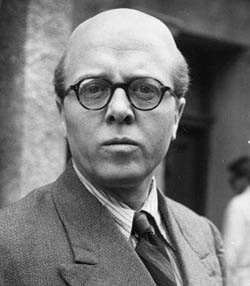

DEVIN McKINNEY • The missing piece in the Beatles’ movie puzzle, the wild card in their deck, is Joe Orton. This enfant terrible of the British theater, in between epatering the ‘60s bourgeoisie with the likes of Entertaining Mr. Sloane and Loot, wrote a screenplay for the Beatles at the commission of producer Walter Shenson. Adapted from an early, unpublished novel and suggestively titled Up Against It (Brit-speak for “under the gun”), the script was violent, sexually transgressive, defiantly sui generis—part Fellini freakshow, part black Ealing Studios farce, part prophecy of every late ‘60s anti-establishment decadence-and-destruction fantasy from How I Won the War to … if… to The Damned—not to mention a sulfurous omen of England herself under Margaret Thatcher.

* * *

Up Against It begins with the expulsion from a provincial town of two young men of no fixed ambition, Ian McTurk (imagine Paul McCartney in the role) and Christopher Low (perhaps played, in alternating scenes, by both George Harrison and Ringo Starr—like the heroine of Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, who was portrayed, for no very obvious reason, by two actresses). Ian is a sexually profligate charmer, Low quixotic and pure of heart. They are banished because Ian has deflowered Rowena Torrence (imagine Julie Christie at full Darling pout), niece of the local high priest, Father Brodie (Richard Attenborough?); present to see them off are the amiably opportunistic Mayor (Dirk Bogarde!), sexually dangerous police official Connie (Claire Bloom!), and plain-Jane secretary Miss Drumgoole (Rita Tushingham!), who is desperately in love with Ian.

Wandering the woods outside of town, Christopher meets and winds up at the mansion of eccentric millionaire Bernard Coates (Victor Spinetti, who else); also present at the mansion is the sinister Connie, who frightens the innocent Low into sexual slavery. Meanwhile Ian has fled the scene, enraged by Miss Drumgoole’s revelation that Rowena is to marry Coates. He comes upon a group of anarchists led by Jack Ramsay (John Lennon), a rootless troublemaker whose plan is to assassinate the new (female) Prime Minister. Also in Ramsay’s ragged cadre are the deposed Mayor, embittered kept boy Christopher, and Miss Drumgoole, now a government clerk out to commit sabotage.

Jack, Ian, and Christopher affect female drag to gain entrance to the Royal Albert Hall, where Jack guns down the PM. They escape. Later, Jack disrupts the Prime Minister’s funeral march with a speech in favor of public debauchery and an end to private perversion. The crowd finds this notion not merely sensible but appealing. A riot ensues, and the three hide out in the newsagent’s shop of Jack’s wizened anarchist father. Ian is lured away by the treacherous Rowena, and captured; Jack and Christopher are cornered by police and shot down.

For the next ten years Ian languishes in prison—before being liberated by the miraculously still-living, and patiently tunnel-digging, Jack. They make their escape through a sewer and into the sea, where they are pulled into a luxury yacht attended by—guess who?—Christopher Low. Seems he is cabin boy to Rowena and Coates, who are now married. A mad tea party follows, attended by all three heroes, Rowena, Coates, the Mayor and his wife, and Miss Drumgoole. Ian again tries and fails to seduce Rowena; while Miss Drumgoole, still in love with Ian, throws herself overboard when he rejects her. Before they can be arrested, Jack, Ian, and Christopher abscond in the lifeboat; they find Miss Drumgoole adrift, whereupon they are caught in a storm.

Ian awakens on a beach and is taken to a hospital, where Connie reappears to draft him into the war now being fought between government and rebel forces. At the recruitment center, he reunites with Jack and Christopher; they convince him to go over to the rebels. The three go off to battle, where Ian is wounded and they again cross paths with Miss Drumgoole. The Mayor turns up, as does Jack’s father; sides are switched again, and still again. Finally the bickering crew crash their stolen ambulance into a lorry carrying wounded—and in an epic disaster scene, a series of escalating conflagrations climaxes in the opening of the earth itself to swallow the dead, the dying, the wounded, and even their scurrying medics. At which point Father Brodie materializes, surrounded in sepulchral procession by the chants and prayers of the faithful, to bless the hellish battlefield. Ian sobs, Christopher kneels in spiritual surrender, and Jack loses his mind.

All are taken prisoner—only to be given medals and honored as heroes: Their initial ambulance crash, it seems, resulted in the winning of the war and defeat of the rebels. Jack’s anarchist father is now a decorated general; the Mayor has been restored to power; and Christopher is engaged to Connie. But in a welter of last-minute reversals, the world is set off-balance yet again. Christopher, appalled once too often by Connie’s virulent sexism, calls off their engagement; Jack’s father finds himself demoted to hotel bellhop; and Ian, though he still loves Rowena, offers himself to the faithful Miss Drumgoole. (“My heart is broken, but everything else is in working order.”) She accepts the proposal of marriage—to all three heroes. Ian, Jack, and Christopher wed Miss Drumgoole in a mass officiated by Father Brodie and attended by the whole happy cast, and the screenplay ends with bride and grooms in polygamous morning-after intimacy, disappearing with squeals of delight under the conjugal sheets.

* * *

Whole chunks of Up Against It are lifted from The Vision of Gombald Proval, a long-unpublished novel Orton wrote in 1961. (It eventually appeared in 1971 under the title Head to Toe.) So the screenplay incorporates Orton visions that long predated his knowledge of the Beatles. It’s arguable to what extent he felt these long-held visions had any specific application to the group, and to what extent he was simply recycling ideas he thought were too good to waste. It’s arguable even to what extent Orton felt Up Against It was a legitimately producible screenplay, in the context of the time and (particularly) of the Beatles as subjects and objects of fame.

But whatever its provenance, the material of Up Against It was formalized in Orton’s mind and set down for sale and consumption (fat chance) as a Beatle product—a Beatle fantasy, if you will, which Orton hoped to set loose as an agent of commerce. And it is certainly among the most winning, imaginative, and unclassifiable Beatle fantasies of all. It is hallucinatory delight to filter Orton’s puckish outrages through a skein of Beatle imagery: The two mesh with a logic not altogether shocking, and the humor gains a dimension when read as satire of the Beatles’ fame.

Again and again, the action of the screenplay invokes real Beatle life—or at least its familiar film representation—only to twist it perversely. A scene of the heroes fleeing a crowd of women sounds awfully familiar, until we remember the boys are wearing drag and the women are bloodthirsty middle-aged politicos—Mrs. Thatcher’s forerunners. Many of Miss Drumgoole’s devotions to Ian (“I understand how he sets all hearts aflame!”) are obvious parodies of fan-rag gush. From a slightly longer perspective, there is truth as well in the screenplay’s spectacle of wild ambiguity—sexual, political, moral—swirling around a band of protagonists who, despite all changes in fashion and ideology, remain essentially unmoved in character and commitment. Up Against It is frequently hilarious (“He’s been wrestling all afternoon with his conscience.” “Who won?”), and probably reads better than it would have filmed—though a director with a free hand and combining the gifts of Godard, Lester, and Buñuel at their peaks might have produced one of the cracked masterpieces of all time, a grand folly on the order of The Loved One or Fitzcarraldo. (What are movies for, if not to inspire such fancies?)

But in any case the film was not made; Brian Epstein’s office returned the screenplay without comment. Clearly the material was found irremediable, though Orton’s petulance at not being treated like a rajah may have played its role in queering the deal. He gave evidence of extreme bitterness over the misbegotten affair: In Prick Up Your Ears (1987), the film of Orton’s life based on John Lahr’s biography, scenarist Alan Bennett imagines the playwright’s extreme anal revenge upon the boys in the band. “What I would like to do at this moment,” grumbles Gary Oldman as Orton, “would be to ease down their Liverpudlian underpants, and ram my Remington up their arses.” (His typewriter, not his revolver.)

But that was another vision destined to go unfulfilled. Orton was found murdered a few months later, beaten to death by his lover, Kenneth Halliwell, who then committed suicide; as Philip Norman notes in Shout!, “A Day in the Life” was played at Orton’s funeral. Up Against It was eventually briefly mounted, by Todd Rundgren, as an off-Broadway musical, and was not a roaring hit. Today this dream of Beatle-image auto-destruction is reprinted, along with the novel that was its foundation, as Head to Toe & Up Against It: A Novel and a Screenplay for the Beatles (Da Capo, 1998), with an introduction by Lahr that draws liberally on Orton’s diary entries. It is well worth reading, and gaping at.

DEVIN

Very interesting piece.

Any objections to my linking to your blog on the official Joe Orton Online website? I’d like to add this to online resources. You’ll find the site at http://www.joeorton.org

Thanks

Alison

Joe Orton Online

Up Against It was first performed as a play in 1985 by L.O.S.T(london) with a specialy composed soundtrack by The Times. it predated the Rod Tungren one.

Thanks for the correction, Mick.

Quick note to add to a very old post: it’s my understanding from John Lahr’s introduction to the published edition of “Up Against It” (coupled with a previously unpublished novel of Orton’s that wound up providing much of the basis for that plot) that when The Beatles passed on his script, Orton re-adapted it, shortening the four men at the center of the story (who would have been our lads) to three.