- Needed: Paid Research Assistant(s) for a Beatle Project - October 28, 2023

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

Folks, this piece was in the editorial queue before Nancy and I decided to put this site on hiatus. To honor my commitment to Faith, I post it here. Enjoy.—MG

BY FAITH CURRENT

St. Peter’s Church, Woolton Village, Liverpool

January 11, 2023

“You’re lookin’ for Eleanor then?” The voice startles me — I’d thought I was alone and anyway, disembodied voices in cemeteries tend to be startling on any account.

I spin around to see an old man regarding me with a cryptic smile. He’s wearing a thick woolen overcoat and carrying a walking stick. Standing in the mist at the edge of the churchyard, he looks for all the world like some sort of mystical Liverpudlian guide fated to appear whenever weary travellers lose their way.

I’m not weary and I haven’t lost my way. Quite the contrary. But it is cold and damp and while that lends the right sort of ambience to wandering through ancient churchyards, it’s also, well, cold and damp, and that makes it less than comfortable to wander through ancient churchyards for any extended length of time.

“Yes.” I nod, accepting his offer of help. “Ta.”

He leads me to a crowded row of grave markers just off the street. “Here she is,” he says, using his walking stick to point to a tall stone.

And here she is indeed, the immortal musical daughter of Lennon and McCartney, in tiny letters halfway down…

And here she is indeed, the immortal musical daughter of Lennon and McCartney, in tiny letters halfway down…

Eleanor Rigby… beloved wife… died 10th Oct 1939, aged 44 years. Asleep.

“An’ there’s McKenzie, too.” the old man adds, pointing his cane at another stone a few down the row from Eleanor’s. “It’s all here, the whole story.”

He’s right. It is all here. Eleanor Rigby, a father named McKenzie, a church yard, a grave. Regardless of the conscious inception of one of the most iconic and poignant songs in music history, the roots of it are right here.

I turn to ask him a question, but the old man is gone, no doubt vanished back into the stones till the next pilgrim in need of direction appears. I’m alone with Eleanor, which is somewhat appropriate because among the collection of associations we have with the name ‘Eleanor Rigby’, the main one is, of course, loneliness. Eleanor Rigby is, arguably, the western world’s first and still only archetypal symbol of loneliness. (Take a look at the Eleanor Rigby statue on Slater Street in Liverpool.)

I’ve come on this journey alone, and although I don’t feel lonely in the classic sense of the word — I love the freedom of travelling by myself — most of my friends don’t understand my soul-deep need to be here, or why this is more than just a nice trip to England to see some cool Beatles things (“oh, and while you’re there, you should go see Big Ben!”), or why my throat tightens and my hands shake standing at the grave of a woman who died almost a century ago and whose name two young men borrowed for a song written almost sixty years ago.

It shouldn’t matter, my friends’ lack of understanding, except that it does. Carl Jung once observed that true loneliness doesn’t come from being physically alone, but from feeling unable to communicate to others the things that matter most to us.

It frustrates me and, truth, also feeds my craving for exceptionalism, to confess that I don’t really trust anyone in my life enough to fully share with them why I feel so passionately connected to this story. That’s the kind of loneliness Jung was talking about. It’s Eleanor Rigby’s loneliness. And it might, possibly, be the reason I’m standing here in the first place.

• • •

It’s almost time to meet Derek, the St. Peter’s parish volunteer who has kindly agreed to show me around, so I take my leave of Eleanor and cross the road to the church hall.

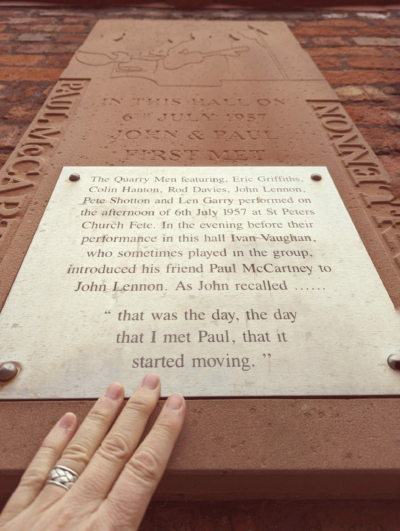

Before meeting Derek, though, I stop at the marker on the outside wall. There, engraved in stone…

In this hall on 6th July 1957, John & Paul first met.

In this hall on 6th July 1957, John & Paul first met.

It’s the same marker that moved me to tears when I first saw it online — which was also, not coincidentally, the exact moment I knew I had to come to Liverpool, despite the considerable inconvenience and cost, to stand where I’m now standing and do what I’m now doing.

I reach my hand up — the marker is mounted higher than eye level, as if to indicate that what happened here is out of reach of ordinary mortals (and also probably to protect it from graffiti) — and I touch.

A shiver runs through me — part thrill, part reverence, part nerves. My mind’s reaction to the marker is the same as it’s been to almost everything since I’ve arrived in Liverpool… I’m here… I’m really here… I can’t believe I’m really here… It’s the one-note monologue of an overstimulated toddler and it constantly threatens to drown out the actual experience of being here. I politely tell my brain to shut it. Yes, we’re here and can we focus on the actual reality in front of us, please and thank you very much?

Derek takes in my nervous anticipation with a gatekeeper’s patience and good humour. He is, I can immediately tell, in possession of the large store of zen-like serenity required for any anointed keeper of a sacred site. More importantly, he’s also in possession of the keys to the church hall .. the actual keys to the actual church hall, I’m here… I’m really here…. which he retrieves from his desk drawer with a conspiratorial smile.

“I assume you’re versed in the history,” he says, as we walk together across the courtyard.

I am, of course. That their mutual friend, Ivan Vaughan, thought John and Paul might get along, and brought Paul to the Fête. That they met for the first time after the Quarrymen’s afternoon show. That Paul was impressed that John didn’t know all the lyrics to “Come Go With Me” and so instead made up his own. That John was impressed that Paul did know all the lyrics to “Twenty Flight Rock” and also how to tune his guitar. That Paul reminded John of Elvis. That John had beer on his breath. That it was — as they say — a match, and that the world owes Ivan Vaughan an extremely well-provisioned gift basket for his service to humanity on that July day.

Derek nods. “Then I’ll just let you have your experience.”

And with that, he opens the door and we step inside, and I really am here now, at the epicentre of everything, the origin point of the Big Bang, the First Cause, and I want to be present for every second of it, but the hyperactive toddler in my head is still stuck on… I’m here… I’m really here… I can’t believe I’m really here... and oh ffs, okay, it’s gonna take awhile, it seems, to actually be here.

Possibly due to his extreme familiarity with the current phase of my “experience,” Derek quietly shows me around, which doesn’t take long, given the hall is much, much smaller than it appears in photographs, and nothing remarkable in and of itself — which is perhaps why it is so remarkable.

Possibly due to his extreme familiarity with the current phase of my “experience,” Derek quietly shows me around, which doesn’t take long, given the hall is much, much smaller than it appears in photographs, and nothing remarkable in and of itself — which is perhaps why it is so remarkable.

The most sacred events in the human canon seem to prefer a plain backdrop — a stable or a bodhi tree, a cave or a prison cell or a simple church hall. The fancy temples and cathedrals are built after the fact, out of our instinctive need to mark the event for posterity.

But the stewards of St. Peter’s haven’t turned this sacred space into a cathedral, nor indeed into anything at all. They’ve let it be exactly what it was on that day in 1957 — an active used-by-the-community church hall. For this small miracle, I’m profoundly grateful, because it means that in a very real way, the two boys who met in this room… this room… this exact room… are still here… and still, just barely, within some kind of mortal reach.

I can feel the pressure of impending tears, and I have enough British-like reserve in me to not want to cry in front of Derek, so I seek refuge in the plainness of the bulletin boards that take up two of the walls, while I figure out how to be here in the way I want to be here.

The boards display photos and a history of the Fête and the Meeting, but also ordinary notices about this month’s community events — a youth group, a rummage sale, a church luncheon. A flyer that reminds parishioners that if you’re going through a difficult circumstance, you’re not alone.

On the board dedicated to the Fête, a faded black and white photo of John with his guitar on the back of the parade truck. Once again, I stretch my hand up — the photo, too, is higher than eye level — and rest my fingers on him. Below John’s photo, a quote from Paul, showcasing his gift for understatement: “He looks good. I wouldn’t mind being in a band with him.”

“You’re a John girl,” Derek smiles.

“I’m…” I want to clarify that I’m a John & Paul girl, but my throat closes up and nothing comes out. The reality of being here is starting to sink in, and perhaps Derek senses that, because now is when he shows me the exact spot where, according to witnesses, the Meeting happened.

Feeling like I’m existentially overstepping on a massive scale, I stand on The Exact Spot. I’m still hanging on, barely, to some sense of composure, but I’m painfully aware that my ability to act like a rational human being is going to fail me at some point and probably fairly soon.

I feel the need — entirely out of personal vanity, mind you — to justify my reaction to Derek. The words come out in choked-back sobs, and I don’t know what they’ll be until I say them because my thoughts have gone from toddler babblings to Bambi on the ice in the classic Disney movie, all skittering limbs and no traction.

“I… I just fell in love,” I manage, barely. “So hard, so deep, that I had to cross an ocean to be here.” It hits me then — all of it, this whole mad journey — and there’s nothing I can do to hold it back. Sniffles, tears, gulps, the full complement of overwhelm, and fucking hell, snot is in imminent danger of appearing and snot is fundamentally incompatible with my whole black leather, tight jeans, Beatle boots persona, and this simply cannot happen. But it is happening, because what the hell else did I think would happen anyway?

Derek tactfully asks if I’d like some time alone, though he doesn’t seem markedly uncomfortable about the whole situation, because of course he’s not. A man uncomfortable with teary-eyed, snot-inducing emotional meltdowns probably wouldn’t last long as the keeper of any sacred site, let alone this one.

I nod my thanks. I want to say more, to express my gratitude at his offer, but I’ve now officially lost my capacity for speech.

He smiles his understanding, tells me he’ll be waiting, when I’m ready, to show me around the churchyard, then discreetly slips out, leaving me to my… experience.

Alone now in the empty hall, I stand motionless in the silence. I have no idea how the next few minutes of my life are going to go, and I’m terribly afraid I’m going to do this wrong. I want whatever I do here to matter, though I’m not sure what I mean by that. I should, I realise, have made some sort of plan, but I’m a creature of impulse — this is how I got here in the first place — and plans are not, in general, my strong suit.

My brain is still stuck… I’m here… I’m really here… I can’t believe I’m really here... and I don’t know how to stop the loop, which is now sounding not unlike the maniacal hidden final track on Pepper. I’m trapped in the album groove.

Finally, my flailing mind finds purchase and comes up with…

Music. Music is how I do this, how I make it matter. And I mean, of course it is. Music is why it all matters in the first place.

My hands twitch for the guitar I don’t have with me. I have my phone, of course, and thus the ability to play virtually any song ever recorded, but I also have a brain that won’t cooperate… I’m here… I’m really here… with even a single song suggestion.

I message a fellow Beatles writer in what I hope is a proximate time zone — “I’m at the church hall. What song should I play?” I’m proud of myself, I sound so, y’know… sane.

But as soon as I hit send, I realise it doesn’t matter which song or even whose song. “Twenty Flight Rock” or “Eleanor Rigby” or “In My Life,” the Beatles or Beethoven, Madonna or Miles Davis, Shania Twain or your favourite indie singer/songwriter. It really, really doesn’t matter, as long as it ignites the soul the way music ignited the souls of John Lennon and Paul McCartney and brought them together in this sacred ordinary place. That’s the magic that made all of this happen, the magic that makes all of it endure. That’s the magic that fills this space, this moment, this experience. That’s why I’m here.

And so with a couple of clicks, music does fill the room and I’m full-on sobbing now, the messy turn-your-guts-inside-out kind, and the self-conscious part of me wonders vaguely if there’s a security camera in the hall, but I doubt it and it doesn’t matter anyway. I couldn’t control this situation if I tried, and I don’t try, because isn’t that the point of all of this, to get swept away by the magic? And if I can’t do that here, in St. Peter’s Church Hall, at the heart of the whole damned thing, then where?

And here’s where I need to apologise, because I’m a professional writer and words are my superpower, but I have none that are truly adequate to the task of describing the next part of the story.

The English language is impoverished when it comes to words for ecstatic experience, and all I come up with are cliches I’ve used too often for lesser experiences, leaving nothing in reserve for the ones that matter. This is what happens when we call regular things “amazing” and “miraculous” and “transcendent” and “awesome” when what we mean is just that they’re pretty fab.

Words fail me… thoughts fail me… the only thing left is the primal, instinctive language of supplication and though I feel like a right nutter for it, I’ll be damned if I’ve come this far only to fuck things up now by being a coward. I give in to the pull I’ve had since I walked in the door and — trusting that I am indeed unobserved — drop to my knees and press my lips to the worn wooden floor.

Words fail me… thoughts fail me… the only thing left is the primal, instinctive language of supplication and though I feel like a right nutter for it, I’ll be damned if I’ve come this far only to fuck things up now by being a coward. I give in to the pull I’ve had since I walked in the door and — trusting that I am indeed unobserved — drop to my knees and press my lips to the worn wooden floor.

For a moment, the world stands still, and the endless loop in my head quiets to the satisfied sigh of a pilgrim having reached their destination… I’m here.

“Thank you…” I whisper in what can only reasonably be described as prayer. “Thank you.”

Ridiculous and absurd? Maybe. Don’t care. It was the right… the only… thing to do.

• • •

It’s tranquil then… and blessedly quiet… and I think maybe I haven’t mucked it all up too badly, until I realise there’s no good way to leave.

There’s never going to be “enough” of being here. There’s never going to be a “right” moment to turn my back and walk away from this place as if it were just a place. There’s just an arbitrarily chosen moment of leaving, indistinguishable from the moment before, save for it being the last one, and it troubles me, deeply, that I can’t find a more meaningful way to go other than to simply go. For the first time, I have a felt understanding of why people walk backwards when they take leave of the Queen. (For the record, I didn’t walk backwards though I’m now kind of wishing I had.)

Derek meets me outside. My eyes are red and my nose is running and any residual dignity I had departed with the floor kiss. But I have regained the power of speech, so I deflect from the mess-that-I-am by asking if other people cry, too.

“Oh yeah,” he nods, so matter-of-factly that I believe him.

“Do you talk about how people react? Afterwards?” What I really mean is, are you going to have a laugh about the writer from America who wept uncontrollably in your church hall, but I don’t say it that way and I don’t really believe that’s the case, which is why I believe him once again, when Derek shakes his head.

“No, not usually,” he says. “We just bear witness and hold the space for those who come.”

I’m still not back to full functioning, but I attempt to tell him how grateful I am. For his time and attention, for the care that everyone at St. Peter’s has taken for the past half-century to protect and steward this story. For the story itself. For all of it, really.

As we walk to the churchyard, Derek tells me about some of those who come. Dying people whose last wish is to stand on the spot where it all began. A young couple from Peru who spent every penny they had so they could tell their kids they’d once been here. The audio engineer who travelled halfway around the world to spend half a day recording the sound of the empty and silent hall.

“It’s all of you,” Derek says. “You remind us of the power of what happened here. Your love is what keeps it all going.”

I nod as we reach the churchyard. I would very much prefer not to start crying again, but…

“Do you think it could happen again?” Derek asks. It feels like more than an idle question, and I’m happy for something wonky to talk about so as to hold the latest round of tears at bay.

“No,” I answer without even having to think about it, because of course I’ve already thought about it. A lot. Maybe too much. “We’re too divided and wrapped up in our petty outrages to be open to anything truly world-changing. If they came today, would we even notice?”

We finish back at Eleanor Rigby’s grave.

…all the lonely people, where do they all come from…

Standing here with Derek and Eleanor and the now-mythic spirit of two extraordinary boys whose passion and defiance changed the world, I realise I’m not alone in this after all.

Whatever our individual reasons, the web of love for John and Paul, for the four of them, for their music, their story, connects us… across geography and time and generations and circumstance, those who come here and those who long to come, those who cry and remember and grieve and celebrate and pay tribute, each in our own way, reminding me that if we’re struggling with anything… even ecstasy and awe… we’re never alone. ◊

A VIDEO TOUR.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zDMVLM69oH_N_TE4AlypB9z4o9-8YP_i/view?usp=sharing

All photos © 2023 Faith Current. FAITH CURRENT is a Beatles writer/scholar specialising in the study of the creative and personal relationship between John Lennon and Paul McCartney, as well as a Beatles fic writer and a regular contributor to Hey Dullblog. She’s a mythologist and professional psychological profiler, and the daughter of a passionate rock music historian, as well as a singer/songwriter. Faith is currently at work on an in-depth book about John and Paul, and a memoir of her journeys to Liverpool and Hamburg (of which this piece is an excerpt). She can be reached at faithcurrent.com.