- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Folks, this is part 2 of Faith Current’s unique, challenging interpretation of The Beatles mid-60s masterpieces. If you haven’t read part 1, do so now. You’ll get more out of this post. Enjoy!—MG

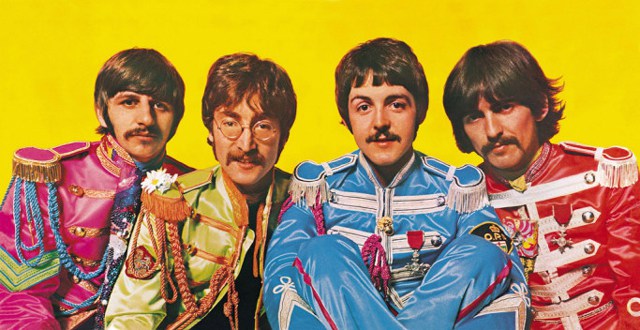

Ringo, John, Paul and George looking with the eyes of love, 1967.

BY FAITH CURRENT—By December of ‘66, the Great Global Revolver Freak-Out is over. The Beatles have freed themselves from the restraints of touring, but they’re still confined–this time in the studio and this time, voluntarily. They have unfinished business with us.

They’re busy remaking Revolver.

I don’t mean track for track, although there are concordances. “Love You Too” becomes “Within You Without You.” The claustrophobia of “Eleanor Rigby” motivates a desperate escape in “She’s Leaving Home.” ”The mania of “Good Day Sunshine” morphs into the mania of “Good Morning.” The experimental psychedelia of “Tomorrow Never Knows” coalesces into “Day in the Life.” A case could be made that “Got to Get You into My Life” softens into “A Little Help from My Friends.”

Please don’t misunderstand. The Beatles aren’t derivative, not even of themselves. It’s just that like all great artists, they have something they’re driven to say and they’re going to keep saying it until we stop rioting and throwing garbage and actually fucking listen. They have no choice, really–to do otherwise would be to give up, to compromise, to sell out and pander, and those aren’t things the Beatles have never been willing to do with their music. The message will be delivered, even if it takes 700 more studio hours to do it.

Don’t be fooled by shiny objects. Sgt. Pepper is presented as the brightly colored child’s picture book version of Revolver, more accessible, less threatening in its affect, but just as dangerous and maybe more so for not seeming quite so dangerous. Splashy graphics grab our attention, printed lyrics are handed out so we can follow along more easily. The Fabs in shiny costumes and hats with feathers (feathers!) woo us with their “look into the camera and radiate love” eyes. Paper cutouts of mustaches and badges amuse the kiddies (that would be us). All of it for the benefit of everyone who got too scared on the first go-round to be able to actually, you know, listen to the music. The lack of subtlety isn’t a bug, it’s a feature.

Sgt. Pepper is Revolver stripped of its violence.

If Revolver was knife’s edge and menace, a session with a dominatrix in a squalid underground Hamburg sex club, Pepper is frothy subversion, the decadence of a Victorian boudoir where pain is delivered by a pretty woman with flowers in her hair who vanishes without remembering to release our restraints.

Now instead of the Beatles locked in an asylum with us looking in, we’re inside with them at a carnival of the absurd, constrained by the velvet cuffs of nostalgia, the pastiche of an earlier time, and the whimsical but vaguely unsettling alter egos that Paul hopes might free them, at least for thirty nine minutes and forty two seconds.

At the end of the ‘66 tour, the Beatles are more alienated from their audience than they’ve ever been. Given the way we’ve treated them, they really don’t like us anymore (okay, Paul maybe still likes us a little bit, but only at a safe distance and for the occasional casual shag). “We’d love to take you home with us,” they gush, but it’s a lie, delivered with sneering irony, and besides they did that already in Help (the movie). Beatles irony is always a clue that something more important is happening beneath the surface, something more radical, more transgressive even than Revolver.

Did you think Sgt Pepper is about peace, love and understanding? Think again. Pepper is all about misdirection, the magician distracting us with one hand while deceiving us with the other. Mischief is afoot, but it’s mischief with dark and subversive purpose.

The mischief is that this time, a splendid time is guaranteed for all, and particularly for the Beatles, mostly because they no longer have to put up with our nonsense. We can hear them but they can’t hear us–they have no interest in hearing us anymore, thank you very much—as they launch into the live show we wouldn’t sit down and shut up long enough for them to perform the year before.

If you can behave, promises Ringo, we’ll try not to sing out of key, but he does a little anyway, his voice just slightly flat, and don’t think for a minute that, with Perfectionist Paul at the helm, that’s not deliberate. They’re testing our ability to deal with discordance. Will you sing along this time? they ask. We’ll try not to be quite so transgressive (a lie), not quite so frightening (another lie). Can you control yourselves and not throw another tantrum, if we offer you a little help from your friends?

Perhaps. After all, it’s getting better all the time (they sing through clenched teeth)… isn’t it? Well, it is for them (except maybe John)–it really couldn’t get much worse. It’s getting worse for us, though, so much worse, though we can’t see that just yet. We’re not meant to, actually. That’s part of the mischief.

Pepper is Paul’s baby, but at this point, there’s no one feeling the madness of confinement more than John, stranded in stockbroker suburbia and trapped in a marriage forced on him by the mores of the times, watching cornflake commercials and tripping on LSD, mostly out of sheer boredom.

That’s why this time, John is our guide for our descent into madness. His mad Ophelia with the sun in her eyes lures us, White Rabbit-style, deeper and deeper into the acid-drenched landscape of a child’s drawing, until we couldn’t find our way out again if we tried. “Lucy”’s not confessional, it’s directive. John’s telling us where to go–to Hell basically (aka the Underworld/subconscious) decorated in pretty colors so’s we don’t notice or mind much. What awaits us at the bottom is the claustrophobic frenzy of “Good Morning”–there’s no madder track on Pepper, save one–and the menace of creepy Mr. Kite, whom you wouldn’t want to trust alone with your children.

Paul, on the other hand, is rather enjoying his confinement this time around. After all, he’s got a Project, and he’s busy obsessively sealing up holes to keep the rain (aka, everybody’s feelings and their attendant messiness) from bollocksing it all up. As always, Paul seeks what little comfort he needs in sex, but this time he doesn’t find it. His seduction of the lovely Rita is thwarted by her sisters, who don’t seem interested in a foursome, and he’s forced into a furtive wank in the bog, panting obscenely to the masturbatory rhythms of Ringo’s drums and desperately hoping to avoid that most maddening of confinements, loneliness in old age (oh, did you think “When I’m 64” was meant to be cute? LOL, as always, lyrically-speaking, Paul is the ultimate unreliable narrator). His other girl makes it out, but that’s a trap too. We all know it’s not going to go the way she thinks it will with the man from the motor trade. There’s a desperate call from a Haight-Ashbury phone booth on the horizon.

Things are getting a little heavier now, and George pops in for a quick wellness check and some exposition, his sitar mimicking the cry of a child waking from a nightmare. But it’s George, remember? He soothes us with words that don’t soothe at all and aren’t intended to. We’re doing this for your own good, he scolds. You didn’t listen the first time, so we have to do it again. It’s all there, the subtext turned to text for the slow kids in the class (that’s us again). Comfort is proffered and then wrenched away, and it all dissolves into mocking laughter at our fears, our ignorance, our blindness to where they’re leading us, the trap they’ve baited while we’ve been distracted by dancing horses and paper mustaches.

The trap is set now and we still don’t see it, foolish children that we are. The band is about to leave the stage, but before they go they have one last act to present.

All of what came before on Revolver and Pepper has led us to this moment.

Close quarters in Studio One recording “Day In The Life,” February 10, 1967.

“Day in the Life” is the Beatles’ master class in the madness of confinement. It’s all right there in the daily papers, after all, and in our calcified daily routines — there’s nothing more maddening, more confining, than the everyday reality we’re all caught in. And it’s here where their trap is finally sprung, where they blow out our minds, wake us up, turn us on, and finally plunge us wholly into madness, as the many-handed beast crashes down onto multiple pianos, pounding out that apocalyptic major E chord–the magician’s triumphant “ta da!” and the final terrifying slamming shut of the gates of the asylum.

This is the trap they’ve laid for us, that they’ve been leading us to starting with Revolver. The trap we’ve been too complacent and clueless to see coming. It’s not the Beatles who are confined at all, not in any way that matters, not anymore and maybe not ever. It’s us. We’re the ones suffering the madness of confinement, trapped in the banality of everyday reality.

As that final chord echoes into the void, the Beatles, cloaked in their disguises, make their escape, departing once and for all the concert stage and its perverted expectations. Sgt Pepper–not Candlestick Park– s their final ticketed performance, the concert that they wanted to perform but couldn’t because no one was listening. The final thing they needed to do to free themselves of the last vestiges of commercial and popular accountability for their art and their lives.

Starting with George’s count-in on “Taxman,” the task the Beatles set themselves to (whether consciously or not is irrelevant, as it always is with great art), has been to make us experience–not understand, but experience–on a gut level the way we’ve all trapped ourselves in the unsustainable madness of ordinary life. Because of the Beatles’ refusal to participate in that madness, by the end of Sgt. Pepper (but really arguably since the very beginning), they are free.

What they choose to do with that freedom, how wisely or unwisely they use it, that’s a story for another day. There are some uncomfortable things that we’ll need to unpack together before we can make sense of that story. For now it’s enough to say that everything they do from here forward will be to satisfy the demands of their own–and only their own–artistic imperatives. They’re sorry, but it’s time to go. They’re finished with us now.

Once again, the Beatles bend the zeitgeist to their will. Once again, everybody goes mad. This time, though, because the production is second-to-none, because Pepper is less overtly threatening and more subversive, we’re actually listening during our collective freak-out and we get the Summer of Love instead of the summer of chaos. Those who get it–and a lot of people do, more than ever before in history, maybe–wake up and shake off the trap of conformity and ordinariness in search of something more meaningful. Some of them find it, most of them don’t, and we all know it doesn’t end well all around. But that’s that same story, again, that we’re saving for another day.

Like the Beatles themselves, Revolver and Pepper are brilliant individually, but together they are transcendent. The Pepper vs Revolver debate is as misguided and child-like and idiotic as the John vs. Paul debate. The pinnacle of the Beatles’ genius isn’t either Revolver or Pepper, it’s both/and–Revolver/Pepper as a single entity, a double album. The two are inextricably bound to one another, conjoined twins connected by “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane.” Each is incomplete without the other. To consider them separately is to completely miss the entire point of not just those two albums, but the entire creative arc of the Beatles music.

Revolver/Pepper, when taken as a single entity (and including “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane”) rises to the artistic and thematic level of Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Divine Comedy, though the closest comparison might be William Blake’s Songs of Innocence. And because of its invention of an entirely new form, its economy of language, its relative accessibility and its extreme relevance to the slow-motion (but rapidly accelerating) collapse of modern culture we’ve been in the midst of since the 1960s, I’d suggest that Revolver/Pepper easily surpasses Milton, Dante and Blake in historical significance and artistry.

The Beatles are and have always been the ultimate tricksters, Merlin-class master magicians of the darkest of arts. Fools on the Hill. There’s a reason Paul occasionally dedicates that song in concert to John, George and Ringo. It’s not about the Maharishi or MLK, not really, not in any interesting way. Paul fibs about that sort of thing, remember? That’s part of the game. He and John are world-class lyrical tricksters. They aren’t going to make it that easy for us. Oh, but wait, that’s the next album, isn’t it? We’re getting ahead of ourselves again.

As the Beatles leave the concert stage for the final time, their manic, delighted laughter at the extraordinary and impossible trick they’ve just pulled off echoes into infinity, trapped in the end groove, repeating endlessly, forever. They’ve done what no one else has ever done and likely never will again on that grand a scale. They’ve managed to rule the world without succumbing to its madness.

They never could see any other way.

Wonderful writing, so much to think about.

I have a thought that’s been looking for a venue, and I wonder if you’ll agree that it’s connected to your thesis. It’s a combination of three things I read recently:

The first was an interview (which I sadly can’t find) where John confirms that when he uses “walrus” he’s (at least partly) thinking of The Walrus And The Carpenter.

This led me to the second thing: the poem and some of its context in Alice. If I recall correctly, in said missing article, John said “maybe I should have said I was the carpenter”

“I like the Walrus best,” said Alice: “because you see he was a little sorry for the poor oysters.”

“He ate more than the Carpenter, though,” said Tweedledee. “You see he held his handkerchief in front, so that the Carpenter couldn’t count how many he took: contrariwise.”

“That was mean!” Alice said indignantly. “Then I like the Carpenter best—if he didn’t eat so many as the Walrus.”

“But he ate as many as he could get,” said Tweedledum.

This was a puzzler. After a pause, Alice began, “Well! They were both very unpleasant characters—”[2]

— Through the Looking-Glass

The third thing was an “about” page on a tumblr (https://zilabee.tumblr.com/about). The relevant section:

“I have overblown emotions I try not to talk about… about how the beatles damaged the soul of the world, just tore a huge rift in it and then refused to mend it. (Because they created so much incredible joy in the world, and it became part of the fabric of the world, but it comes with this side salad of pure agony and now that’s part of the fabric too, just sitting there inside everybody, and there is no solving it and I know it’s overblown complicated emotions that aren’t real, but I feel like we’re allowed to be upset that they made something so beautiful and then tarnished the hell out of it in their human way.)”

Something about the combination of these three things made me ask: in John’s mind, are we the oysters?

Not to thread-jack here, @Meaigs, but I took a peep at that About page and…wow.

Obsessions are not truly about the object of the obsession. They are the mind/spirit trying to process something big in the person’s own life or circumstances that has gotten stuck somehow; and the very wise and usually benign solution is a kind of substitution. When a person finds themselves becoming obsessed, that’s a strong signal to limit one’s exposure to that thing, back away, and try to figure out what the obsession is really about–untangle the substitution.

Obsessions are painful, and usually not useful. They seem to reveal important truths, but do not, and are almost useless in communicating with others because they are an altered mindstate. Trying to communicate why something obsesses you or conclusions you’ve come to about it, is a bit like Paul getting high and explaining “reality has seven levels.”

The internet allows people to find others who are similarly obsessed, and together they confirm each other’s biases, and reinforce the obsessed worldview. They shut out the pressure of the outer world, the pressure that is the only chance to wake up. This makes it even harder to uncover what algebra the mind is using, what “The Beatles” or “John and Paul” or “Faul” or whatever is substituting for in one’s life. One must have a really clear understanding of oneself and one’s own mind, plus the belief that the pain can leave, and the desire to help it leave. The obsessed person does not WANT the pain to leave. The pain has become their identity.

If you perceive in The Beatles–a quartet of strangers, two of whom are dead–“a side salad of pure agony” FOR ANY REASON, it is time to turn off The Beatles for a good long while and find out where that agony you’re feeling is coming from. It’s not The Beatles. Even if the answer turns out to be something unchangeable like “my fear of death” or “the seeming isolation from other beings,” it is much better to work with that emotion directly. Working with such things is why we’re here.

Picking at scabs can hurt in a really satisfying way. Do it long enough and the scab can get infected. Act habitually–keep picking that infected scab–and you’ll die.

I don’t completely disagree Michael, that about page made me pretty uncomfortable too.

However, I have benefited so much from giving myself free-rein this year to pursue my obsession with the Beatles. I have always had obsessive tendencies, and always been afraid of them, but for whatever reason I decided to try out a different approach this time. There have been times when I’ve been pretty overwhelmed by my feelings about John and Paul’s relationship in particular, but I’ve recently realised that I see parallels there with an old relationship I really need to process, and those parallels are helping me think about that relationship in new ways. I think that this kind of obsessive interest, handled well, can be a tool for dealing with the core emotion.

Maybe that doesn’t fit “obsession” the way you’re defining it? It can certainly spiral very easily into something destructive, but I think maybe the mechanism has the potential to be useful.

@meaigs, the way you used/are using your obsession is precisely the method I was suggesting in my comment. To realize what it echoes in your own life, and examine (and perhaps resolve) that content, not get stuck in the top-level obsession.

To be clear: I do not mean to criticize the person writing that page. I wish, if possible, for them to identify what is causing them such pain, resolve it, and be happy.

My gut feeling is that people often look to an obsession to give their lives some colour they feel is lacking elsewhere, and if the obsession involves people then hero-worship is rarely far behind. Once the obsessive discovers their hero has feet of clay, rather than letting go of the obsession they remain fixated, but in an angry way: ‘How could you betray me.’ The Beatles and Dylan, as the deepest artists in the rock idiom and 2 of the most popular, have attracted more of this kind of curdling fandom than anyone else. It’s why the Beatles made Let It Be (‘trousers down’) and Bob made Self Portrait (‘load it up with crap’). It’s most obvious with your AJ Webermans and Mark Chapmans, but it’s there in a lot of the respectable scholarship too. You see it when Clinton Heylin goes from writing genuinely useful books about Dylan’s songwriting to axe-grinding biographies that set out to contradict music’s most compulsive myth-maker on point of fact after point of fact (why bother? After you’ve caught Dylan in a couple of lies, is there any need to catch him in a thousand more? What emotional itch is being scratched here?). And you get it when Michael Gray calls a latter period Dylan interview ‘vile’, or dismisses his Sinatra records out of hand because, for him, the purpose of rock was to wipe jazz away for good. Was it? Why should Dylan agree with such a narrow Boomerish perspective on the music he grew up on? If he ever agreed, can he not change his mind over time as he matures and sees the good in more and more things? And do sweeping statements like this not remind you of the people who cried foul when Dylan switched from folk to rock in the first place? For fans like Gray (whose writing I love by the way), Dylan is a man frozen in time – that B&W, smart-aleck, nihilistic, androgynous, limitlessly cool being who bestrode the earth in 1965. Any of his caustic excesses back then are telling truth to power, and the same excesses now are seen as vile.

.

There’s a fundamental refusal there to accept the inherent contradictoriness and transitoriness of life. The same oversimplification of things-as-they-are that gives birth to the obsession in the first place also prevents the person from ever fully *seeing* the object of their obsession.

.

Don’t mean to sound judgy – we’re all coping with (and avoiding) reality in our own ways, the tendencies I’m describing are common as mud, and if I didn’t share some of the psychology of the superfan I wouldn’t be here. But this stuff is worth teasing out.

Love this, thank you @justin.

I clicked on the Archives and left in short order, but not before learning that Nod Your Head is about oral sex (I couldn’t get past the banality of the song to make that connection), and that criticism of Paul is misogyny.

Love it Faith. While I agreed with your take on Revolver 100%, I personally find Pepper sunnier than you do. But plenty of people have called Pepper sunny already, and I’m here for new perspectives and passionate writing. Job done here. (For me, the “flowers and rainbows” artist that reads more as despairing and bludgeoning is one Jimi Hendrix. OK the lyrics might be hippyish, but are people actually *listening* to that guitar? Like, at all? Those are the howls of the freakin’ damned!)

.

Couldn’t agree more on your central thesis, though: this is the Beatles giving the cheeriest of middle fingers to a world that wanted them to play on demand and wouldn’t even listen when they did. It just so happened that their middle finger suited the tenor of the times perfectly, whereas Dylan’s 1967 middle finger didn’t (sure John Wesley Harding would go on to influence tons of what came afterwards, but that doesn’t mean it hit the popular consciousness that hard in itself).

.

Have you read Revolution in the Head? Your piece reminds me of Ian Macdonald’s theory that the band’s newfound insistence that they be *totally* free worked for them in the short term, but was their undoing in the long term, as the music on MMT and White got ever more unfocused and self-indulgent and the lyrics ever more navel-gazing (when they weren’t outright nonsensical).

.

But this is the same man who says Revolution #9 was the most important thing the band ever did, so what does he know.