- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

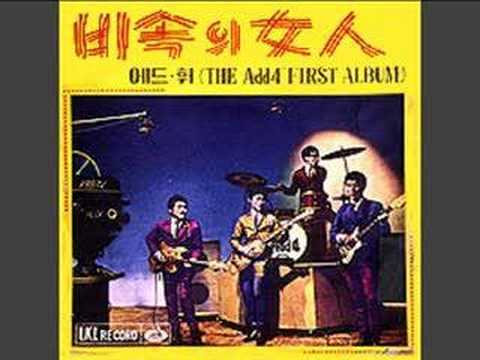

Folks, a longtime HD commenter pointed me to some recent Beatle-related musings on their Substack, which I liked enough to repost here. Enjoy. —MG

BY WABI SABI • My favourite music reviewer, George Starostin, has been writing about the Beatles for a long time. On his old site, he takes on both the naivety of the Beatles superfan who thinks the band did everything first, and the pedantic factchecking of the rock snob who points out there’s very little the foursome are credited with that hadn’t been introduced to the scene a couple of months earlier by someone less celebrated.

(Not that I don’t get the impulse, factcheckers. It is frustrating to read pundit after pundit talking about the innovations of the ’60s without once mentioning Frank Zappa, who arguably gave rock music its first double album, concept album and abstract sound collage on his first record, and hipped audiences to the wah-wah pedal long before Hendrix took his first steps along the watchtower.)

Starostin takes a “Golden Mean” approach to the Beatles, arguing that no, they didn’t invent music, and no, that doesn’t mean they did nothing at all to push rock ’n’ roll forward. The band’s job was to take the radical innovations of other people and do them better, so that the new ideas suddenly made just as much musical and emotional sense to the average listener as the old ones: ‘They could take traditional forms — rock ’n’ roll, Tin Pan Alley, lounge muzak even — and imbue them with new content, as well as pour old content into new forms. It took the Beatles to make people believe pop music was more than just a form of shallow, temporary entertainment — here today, gone tomorrow. And it took the Beatles to make people believe, if only for a few years, that music could actually change the world.’

I love this argument, because I think that people who revere music as High Art often forget that its main job has always been to bind people together — as many people as possible. The reason Zappa doesn’t get credit for his dozens of innovations is because his music’s weird. People like me like it, but my parents wouldn’t and most other people in the world are never going to either.

That doesn’t mean you can’t set the historical record straight (I’m telling ya, Brian Wilson wasn’t the first rock artist to use the recording studio as an instrument in its own right! The Soul Patched One beat him to it!!). But at the end of the day musical greatness isn’t about historical point-scoring, it’s about integrating content, form, function, beauty, mathematical elegance, emotional resonance and a million other things until you’ve created something capable of speaking to people of all ages, personalities and backgrounds. The Beatles wrote guitar-pop songs that were as good as, or better than, the classics from the Great American Songbook. And so they moved the spirit of music forward.

Obviously, it helped that they were really really really good at writing melodies. And keeping up with trends, when they weren’t setting the trends themselves. And trying out every musical style under the sun and being amazing at all of them.

But I think maybe the thing that makes the Beatles most special — and puts them at the very top of my personal pantheon — is the way they combine things that don’t go together. Life is nothing if not relentlessly paradoxical, so the more paradoxes your music contains, the more of life’s bittersweet symphony it’s going to encompass. I’m not even talking about the Fabs’ legendary musical diversity here: yes, the White Album alone is an encyclopedia of music genres, but much more impressive than the band’s formal versatility is their ability to inhabit every variety of human emotion and experience. The Beatles are the most popular band of all time because they expressed so many different facets of what it feels like to live on this planet that everyone can find at least one song in the 200 that speaks to them.

In other words, their body of work is just a mass of contradictions. They say you can’t know joy without sorrow or heaven without hell, and in their brief time on earth the band plumbed the depths of both. Radiant enough to move you to tears yet relatable enough to appeal to just about anyone, the music was made by men who were somehow head-scratchingly eccentric and reassuringly normal all at once, walking paradoxes who never lost sight of their working class Liverpudlian roots but thought nothing of abandoning Swinging London for an Indian ashram at the height of their fame.

Men who were so joined at the hip a rival dubbed them the ‘four-headed monster’, yet so wildly different the internal contradictions broke them apart after eight short years in the spotlight. Who courted the world then begged it to leave them alone, and embraced starry-eyed mysticism and sordid pettiness with equal enthusiasm. The conflicts carry over to the tides and ripples of the individuals’ personalities: George the hard-partying ascetic; Ringo the happy-go-lucky wife-beater; John the socialist hoarder; Paul the populist control freak.

I don’t think you need to be a “good person” to be a great artist — and if you want to be a rich ’n’ famous one it’s probably an active hindrance — but I do think you need to be an intense person. The Beatles, to a man, were intense people, driven enough to live in Hamburg squalor in the pursuit of fame and big-hearted enough to consistently use that fame to promote peace and love; tough enough to withstand years of relentless pressure and attention but sensitive enough to come out of the experience with permanent scars. They cried and showed each other affection in a way that men from their time and place just didn’t. They felt deeply, loved passionately and burned to communicate those feelings to as many people as would listen.

It’s all there in the songs. The early singles communicate a level of joyful abandonment, a wonder in the simple fact of being alive, that’s hard to come by in white music of any era. But this is the same group that gave us ‘Feel so suicidal, even hate my rock ’n’ roll’, and meant it. It doesn’t get more experiencing-the-world-for-the-first-time earnest than “There’s a Place” or “Because”. And it doesn’t get more sardonically world-weary than “Good Morning Good Morning” or “Love You To”. “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” is the simplest lyric of all time. And “I Am the Walrus” is the most convoluted. From the second it kicks off with the magic chord, A Hard Day’s Night sweeps you up in a great bear hug and never lets go. Two short years later we get Revolver, a record as awe-inspiringly glacial, as icily impersonal as the music of the spheres itself.

The catalogue effortlessly straddles art and commerce, as well as what used to be called “high” and “low” culture before those kinds of distinctions got flattened out and made irrelevant (largely by artists like the Beatles). Rock, pop, blues, folk, avant-garde, jazz, literature, advertising, politics, love, hate, indifference — everything was grist to the mill, with nothing privileged above anything else.

The band could pump out catchy melody after catchy melody without making a formula out of it like Max Martin, and touch on misery and rage without making a career out of it like Radiohead or Nirvana. Their MO was to hoover up whatever happened to be in front of them, chew it up, spit out a Beatlefied version of it for the listener’s pleasure, and then move on to the next thing.

On and on the reconciliations of opposites go: the band aimed for your brain, your heart and your feet all at once. They symbolised youthful revolution but insisted on bringing the parents along for the ride. They were more refined than the heavy bands, more credible than the soft bands, more accomplished than the bar bands and more grounded than the art bands. The early recordings grafted the tenderest of melodies onto the rowdiest of musical backings. The later recordings were meticulously conceived and produced but riddled with happy accidents and mistakes. The arrangements fused neo-classical tradition and discipline with avant-garde anarchism and boundary-pushing. To this day the songs summarise their era better than any other music of the time, while being less dated than the vast majority of it.

The band’s reward for all this is that they’re equally loved by people who barely like music and those who have devoted their lives to appreciating it. Sometimes everyone believes something because it’s true, and sometimes everyone likes something because it’s good. You can’t be all things to all people, but the Beatles were, and are.

And they’re my favourite band. That’s all I want to say.

Interesting that he/she credits Zappa as being the first to use the studio as an instrument. I know this is a point of contention among music fans-one that is unfortunately made harder by the trouble in defining what is actually meant by an instrument.

I would argue however, that Joe Meek had this vision starting as early as 1956/7 when he recorded Humphrey Littleton playing Bad Penny Blues. He toyed around with microphone placement, bringing the drums forward in the mix, echo, etc. Sounds uneventful today, but back then it was a new approach to studio work.

Granted Meek was not a musician but rather a producer, yet he was definitely actively pursuing the concept of the studio as being an important element in recording.

Btw, Paul McCartney lifted the opening of this song for Lady Madonna.

https://youtu.be/XnCfEzayD6M

There seems to be a fashionable craze on YouTube these days to trawl through Beatles songs to find comparisons with others. I don’t know why. The Beatles were the first to acknowledge they were influenced and inspired by others. The great classical composers borrowed from each other constantly; indeed it was considered an honour. There are thousands of songs out there, many with snippets reminiscent of others. Some consciously or unconsciously, or purely by chance. It would be a long, exhausting process to analyse all of them. It’s curious as to why historical point-scoring has become important to many people. Has the technological age dulled our cultural collective senses to such an extent that to purely listen is no longer enough? Using the Beatles as an example, the internet has allowed a cavalcade of what individuals think of as under/overrated, their top fives/tens, what they love and what they hate, ad nauseum. Interesting to begin with, now endlessly tedious. Personally, I’m not having the opinions of wet blankets and damp squibs destroy my love of the Beatles. The songs are deeply personal to me as they should be to others. @Neal, I agree with you about Joe Meek, a brilliant overlooked producer. However, Paul did not lift the intro to Lady Madonna from Bad Penny Blues.(I’m getting this in!) If anything, he was wanting to emulate Fats Domino. The song has been widely discussed by musicologists who have generally concurred that despite surface similarites, both pieces are dissimilar in their chord progressions and underlying structures. I’m not sure if I remember correctly, but didn’t George Martin produce Bad Penny Blues in the fifties? But does all this matter anyway? Michael has explained it well enough already. And to illustrate it, Chuck Berry, bless him, could quibble to eternity over Come Together but Lennon’s song is the far superior one in my opinion.

Ah here, you can’t call that “lifting”. If no-one was allowed to be inspired by other music, or do music in the same style as someone else, we’d have nothing at all. I’m with Elvis Costello on this one:

https://twitter.com/ElvisCostello/status/1409567943520931847

—

This is fine by me, Billy.

It’s how rock and roll works. You take the broken pieces of another thrill and make a brand new toy. That’s what I did. #subterreaneanhomesickblues #toomuchmonkeybusiness

Surely Sam Phillips was one of the first to turn his studio into an instrument?

Here is a good article that explores some of the stuff he did at Sun Records:

https://www.popularmechanics.com/culture/music/a22237/sam-phillips-sun-studio/

Thank you Baboomska for the link to the Sam Phillips story.

I have lately been doing quite a bit of reading about Joe Meek and completely forgot about Phillips. Interesting how these two men, thousands of miles apart, envisioned what they wanted to capture and create. What we would give to be able to go back in the time machine and watch Phillips at work with the likes of Elvis, Ike, and B.B. King.

Great stuff. Thanks!

I plead not guilty meaigs! I admit that lifted indeed has an air of felonious intent about it, but it was shorthand for “was inspired by.” So many sounds and chords float about I am surprised that musicians and producers can keep track of them as well as they do. I’ll defer to Lara if the experts had dissected this one to death. I think we can be certain that even with Paul’s quips about nicking a sound here and there that he enjoyed an embarrassment of riches when it came to coming up with new music.

@Lara,

Barry Cleveland’s book Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques (a very interesting volume btw) describes Meek as working as the engineer with Denis Preston as producer at IBC in April 1956 when they recorded Humphrey Littleton. It was released on Parlaphone. George Martin was the A&R man at Parlaphone at the time but was apparently not involved in this recording.

I agree wholeheartedly with you about rankings and ratings and lists. What happened to the pleasure of just listening?

Interesting how aggressive Joe was with limiting and compression on this. He defineltely was going where not many other producers or engineers were at that time.

I confess I’m one of those insufferable people who likes uncovering obscure songs that influenced other more popular songs. I don’t do it out of vindictiveness or any desire to debunk, I just like exploring the evolution of melodies and ideas through the decades.

I’ve found various old records that inspired Beatle music (some of them were hiding in plain sight in Lennon’s home jukebox) but I never heard any obvious examples of JP&G blatantly ripping off someone else’s song. They would often borrow a musical idea and then improve on it. I can’t think of a single Beatles composition that made me say “This is an obvious rip-off!”

A lovely post, thank you Wabi Sabi!

I have had many conversations where I have been faced with the impulse to either lionise or completely dismiss a given artist’s body of work within the context of their field (they have been equally revealing in getting me to reflect on my own tendencies to do so and why), so I really appreciate the nuance you brought to the discussion of the Beatles’ musical influence by emphasising how they were very much in dialogue with and drawing from their contemporaries and antecedents while also acknowledging their significant contributions to music and the shaping of celebrity.

Hope you have a good day!

Thanks Ava! Yes, I’m definitely in the camp that says more context makes you appreciate an artist more, not less. Have a good day yourself 🙂