- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Whatever time you’re reading this, chances are I’m doing the same thing: furiously pedaling my bike en route to my local repertory movie theater, fifteen minutes late for some old movie, with no lights (I know I know) and some truly awful Beatles outtake blaring in my ears.

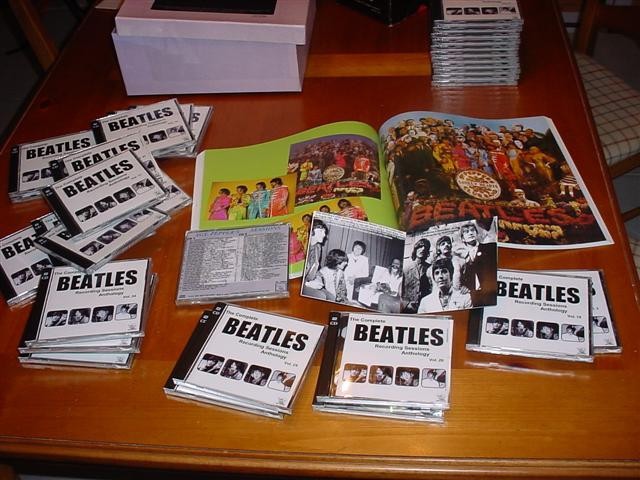

Probably 25% of all the room on my iPhone is taken up by Artifacts I and II, the Beatle bootleg set that basically forced the release of The Beatles Anthology. 25% more are a bunch of digipaks, from Kinfauns to Chaos to Pepper in mono. And because it’s on shuffle, I can go from some 1957 living room jam to “Mailman, Bring Me No More Blues” to 50,000 people screeching in Shea Stadium. This is jarring, and unpleasant. “Sour Milk Sea” is a truly terrible song. So why don’t I delete them? Why don’t I pull all those murky, misbegotten tracks off my phone and, I dunno, listen to something actually good like Antonio Carlos Jobim?

Habit? It’s more than habit. It is (and every bit of Buddhist meditation makes me laugh to say this) who I am.

From about nine to seventeen, I was a kid on a mission. Collecting Beatles bootlegs scratched several of my obsessions simultaneously: the Fabs, history, and secret things. So I spent a non-negligible portion of my waking hours in dusty, soon-to-be-padlocked ex-head shops, looking through bins for immortal LPs like File Under: Beatles. (When I finally found a copy, on a trip to visit my grandmother in Baltimore, she popped my balloon. “Don’t tell your grandpa that record is illegal. He’d be very disappointed.”) Most of the stuff I bought was expensive—$30 was five hours working at the drugstore—and horrible (I don’t just dislike the Twickenham Sessions, I actively resent them), but I kept hunting.

My bootleg lust went dormant when I went off to Yale in 1987, but returned with a vengeance after the broadcast of The Beatles Anthology (“on A-Beatles-C”) which I watched with a bunch of recent grads, all of us crammed into my tiny studio on West 11th Street. They liked it all right, despite my constant running commentary, but I loved it, and by the time they left, my craving for bootlegs was back.

The popularity of the Anthology had a peculiar side-effect: vindication. All those demos for also-ran bands, and half-finished versions of songs deemed not good enough—each of which had thrilled me as a kid—were suddenly known and talked about, valued by the culture at large. And, thanks to the loophole in Italian copyright law that had forced Anthology to happen in the first place, it all became a lot easier to find. So my passion enjoyed a slight renaissance, as finally all the tracks that poor John Barrett had remixed as he was dying of cancer, all the songs those of us nerds at Beatlefest ’84 had spoken of giddily, were suddenly in every independent record store (though never Bleecker Bob’s, something I never forgave it for). And all of it pristine CD quality: beautiful box sets like Artifacts, or the 16-disc Great Dane BBC completist’s dream. I was much too broke to buy any of it, but it was nice to know that the tracks were finally getting out there, and other people were getting into my old hobby.

There’s a picture of me at eight months, probably the first picture of myself that I recognize. It’s extravagantly blurry, as only a pre-iPhone photo can be, and shows me sitting in my high chair. Shirtless, in a diaper, flashing a smile of exactly four teeth, I’m holding a blue-headed mallet from my Fisher-Price xylophone, and banging like mad on the plastic tray in front of me. “You were listening to the White Album,” my mom said. “You always went crazy when you heard ‘Back in the USSR.'”

My love of bootlegs is inextricably linked with my lifelong love of the band. I’m sure I’ve said this before, but from about eight onward, I’d listen to their working tapes over and over, tracking the changes in my mind, attempting to figure out a code—a method to spin straw into gold that I could apply to my own creative work. Because I’m still in a creative field, this is still the sonic soup I swim in. Today everything is available to everyone online, so it’s difficult to describe the thrill of finding something no one else you know has ever heard, and the intimacy of listening to something private to John, Paul, George and Ringo. You either understand this, or you don’t. First-generation, original fans, in my experience, don’t get it. Do fans born after 1985? You tell me.

As I wrote the above, I suddenly realized that one of my sweetest adult memories involves Beatles bootlegs. In October 2003, I took a trip to New York. My first book had finally exited the bestseller lists in the UK, but was still selling well worldwide. Two weeks before, I’d just finished the sequel; they’d given me a ridiculous six weeks, and I hit that deadline—I hadn’t yet realized that you can say “no” to a publisher. Anyway, I was in the mood to celebrate.

I was sick and getting sicker, but for the first time in my life I had a bit of scratch. So I decided to take my wife to New York, stay in the Yale Club, and make it all tax-deductible by finding a new agent. My previous agent had done me dirty, as they do, but with a million-copy bestseller under my belt, surely there was someone in the publishing business who could see that I was a goldmine. I was looking for someone who took written comedy as seriously as I did, and could handle all the business stuff, so I could concentrate on writing two or three parodies a year, each selling 100,000 copies at least. Together he/she and I would create a series of books that would give me stability and prosperity, would finance the dreams I had by doing smart investments like fx trading by VT markets.

Well, I spent a solid week holed up on 44th and Vanderbilt, meeting agent after agent, going out for pastrami sandwiches, and listening to reasons why a person like me—who’d just sold more books than The Onion—would have to knuckle down and play ball and maybe, if we were lucky, get $12,000 advances. Which was not enough to build a career on, then or now.

So that last night, I was pretty gloomy. Since age 11 or so, I’d assumed that a big success—the success I’d painstakingly planned and practiced for, the thing that I fell asleep thinking about, woke up raring to make happen, and dreamed about in-between—would open all the doors that were closed. That was turning out not to be true. I finished dinner with my last prospective agent—a very nice middle-aged woman who’d never heard of Doug Kenney or Henry Beard, and who “couldn’t believe that their Tolkien parody hadn’t been sued”—and got into a cab heading back to the Club. A million books later, things remained fucked.

I don’t know why I told the cabbie to keep heading downtown, back to my old neighborhood in the West Village. Maybe it was just nostalgia; I’d loved living down there, even though it was a constant scramble to pay my rent. Or maybe it was to show myself that, in spite of the deep and profound idiocy of American publishing, things had genuinely changed for me. Where five years before I frequently had to figure out how to feed myself and my dear little Fifi on $3 a day (one 89¢ can of black beans, one $1.09 bag of corn chips, and a 99¢ box of Alley Cat, in case you’re wondering), this night I was back in New York fucking City, staying in a nice hotel, married to a great person, and even had some money in the bank.

The cab dropped me off at the Corner Bistro on Eighth Avenue and Jane, but I suddenly realized why I only liked that place for 2 AM burgers after marathon writing jags; at nine, my old haunt was too filled with baby bankers for me to push my way in. So I turned south at Larry Kramer’s apartment building, hit Bleecker Street, and walked east. It was a lovely, warm night about this time of year and, it being New York, still a bit sticky. Walking for me is sweaty work under the best of circumstances, so when I saw that Bleecker Street Records was still open, an ancient air-conditioner wheezing and chugging above the door, I braved the drips and went in.

“We’re about to close,” the guy behind the counter said, so I didn’t dawdle. I went to the Beatles section by reflex, and started flipping through the racks of CDs. Within five minutes I’d found digipaks of Help!, Rubber Soul, Revolver, Sgt Pepper in mono, MMT and the Christmas albums. For the first time in my life, all the bootlegs I’d wanted most were right here—and I had the money to buy them! I snapped them up quickly, as if someone was going to burst in and stop me. Five minutes later, I was in a cab back up town, already imagining how to explain to Kate how wonderful this felt.

That night, on the seventh floor of the Yale Club, we blasted Sgt. Pepper in mono as I sat in the tub and she packed for our early flight. I still have all those CDs. They’ve stuck with me through the ending of my book career, my illness and near-death, three cats, The American Bystander…Someday, I’ll probably will them to some nonplussed relative. But every Christmas morning until then, I’ll listen to the Christmas albums on my bogus Odeon digipak. Often as I write these posts, the others play on my iMac. They are some of my favorite possessions.

Do any of you have Beatle bootleg stories? Tell ’em in the comments.

In the mid 80s, I placed an ad in Goldmine asking tape traders to take pity on a newbie who only had blanks to trade. I was gifted with every imaginable bootleg, all FREE, all on TDK SA-90s, all wrapped in brown paper packaging from strangers who were absolutely GIDDY to share. Of all the tapes, a sampling of BBC shows was my favorite. I listened to it endlessly, delighted not only by songs I’d never heard (“Lonesome Tears in My Eyes”, “Soldier of Love”, etc.), but the dialog, the humor. It was almost too much to take in. Later, I sourced the Great Dane set, Artifacts, etc, all on CD, but that BBC cassette…I should bronze that thing. 🙂

YES! This is what I’m talkinf about.

.

I remember going over to a friend’s house and him giving me Dakota Beatle Demos, stars of 63 and one of the Unsurpassed Masters. It was Christmas in July.

Michael, love your bootleg stories! Please post that picture of a very young you banging on a toy xylophone to accompany “Back in the USSR”!

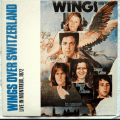

My favorite bootleg — not to listen to, but as an object — was the Wings Over Switzerland CD I wrote this HD post about back in 2013. The goofy, totally incorrect song titles and the terrible cover art make me smile. I still wish McCartney had actually written and performed a song called “Radio Shop” or “Fiper in the Body.” There’s still time, Sir Paul!

I’ll get my mom to scan it, Nancy! You will recognize me immediately. 🙂

.

By the way, I’ve always loved that post of yours, and 100% concur with the songs. “Fiper in the body” is a number-one hit waiting to happen.

And now I can’t be bothered to listen to any of the recently released outtakes from SPLHCB, WA, or AR. Go figure. I must think I’ve heard it all at this point. 🙂

Well, I am an old beatles french fan, and this beatleg story was exactly what we have lived in those years, before internet. WELL DONE!

My passion is listening the fab four composing, rehearsing just before the best take was chosen by PAUL or JOHN, or GEORGE or RINGO.

If you are interested, contact me!

Regards,

Régis

Regis, what are you favorite bootlegs/tracks?

Hello Michael, i also noticed you told us about a nice beatleg collection (anthology) : nice one! But i prefer a more fresh one, the complete recording sessions collection, a very good one with pretty nice and rare outakes.

My favorite tracks concern four different periods:

-the please please sessions (every song from the album),

– the revolver sessions (the whole album) for the quality of these sessions is amazing!

-1968 sessions, especially Hey bulldog and Lady Madonna, and of course the white albums, even since the remastered ones (2018)

-the get back sessions, but my favorite titles are those from the different get back versions ( the second mix and the last one).

Regards, Régis

Regis, are these all Purple Chick torrents?

Hello Michael, as you know, PC CDS were quite fine, but since 2010-2011 there were new material including rockband versions (like secret garden and back to the basis) and some of these recordings were high quality.

My favorite sessions come from these new sources. For the Revolver sessions, one nice collection comes from Granny smith cds. Get back material are all around, even on the beatlesource and special get back sites.

But, these days, some good fans make a splendid work and remix some of the tapes, with sometimes an incredible superb sound!

Regards,

Régis