- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

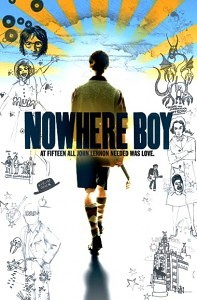

Poster for “Nowhere Boy,” the Lennon biopic, 2010.

If you love The Beatles, the idea of a movie based on John Lennon’s teenage years is guaranteed to cause mild discomfort, as your leaping heart presses against your rising gorge. (Of course, we all agree that a comedy/mystery based on Lennon’s later life is completely OK. By the way, thanks to the hundreds of people who downloaded Life After Death for Beginners yesterday. I hope you all enjoy it.) Faced with Nowhere Boy then, the logical left-brain is definite: “The world does not need John-Julia slash.” At the same moment, however, your right hemisphere is screaming, “I GOTTA SEE THIS.”

Well. I saw the West Coast premiere of Nowhere Boy last night, and YOU GOTTA SEE THIS.

A Nowhere Boy review? But of course

I admit: Me digging Nowhere Boy is like a bee giving two antennae up to Chrysanthemum porn. Very few people who plunk down ten clams to watch this will have spent the previous three years trying to get inside John Lennon’s head, and those who have, are incarcerated. But for me, last night, Nowhere Boy was probably the best non-Beatle Beatle movie ever.

First, the casting is superb—Aaron Johnson is completely believable as the young Lennon. Let me say that again, because for me it was like winning the Irish Sweepstakes: you absolutely believe that this is what the 16-year-old John Lennon was like. Smart, but wide-eyed; more bluff than tough; tender and violent and completely confused about which is right when; and saddest of all, utterly unequipped by his time and place to deal with any strong emotion. Nowhere Boy‘s Lennon is a kid ready to explode, and whether in a good way or a bad one, is completely up to Fate. Lennon himself often mused about what might’ve happened to him if not for The Beatles. Prison or the army were his guesses, and Johnson’s characterization shows that. The young actor’s features, accent, mannerisms—really good. As you might expect, the whole movie hangs on his performance. Fortunately, it’s superb.

Kristin Scott-Thomas isn’t given much to do—“Okay, for this take, read angrier“—but she’s rock-solid as Mimi, the brittle battleaxe with the heart of gold (or at least plating). Even more important is Anne Marie Duff’s Julia. The high-strung, divided character could’ve easily been unsympathetic, but she pulls it off with a sort of blowzy intensity that rings true with the facts of Julia’s life. Relatives often talk about how magnetic Julia was, how attractive, how talented—but then we look at her life and see one catastrophic decision after another. Nowhere Boy hints at Julia’s probable manic-depression, something that Lennon almost certainly suffered from himself. Certainly he inherited Julia’s talent for emotional car crashes, along with her charisma.

Digging John Lennon

Like his brain chemistry, the circumstances of Lennon’s childhood—the mixture of abandonment and helicopter parenting, repression and license, truth and lies—are the key to understanding him as an artist, and a person. Ignoring this stuff because it’s unprovable, unpleasant, or both, is the reason so much of what’s been written about Lennon feels like gussied-up PR. In the case of semi-authorized biographers Ray Coleman and Philip Norman, I chalk it up to British reserve—products of a certain age, these guys seem to wish not to pry. And so we’re left with respectful portraits that feel airbrushed at best, and at worst actually retard our understanding of the man. There was a time to respect John Lennon’s privacy, and it was called “when he was alive.” We cannot expiate Mark David Chapman by airbrushing his victim. Now is the time where we must try to understand Lennon, now before the primary sources die, and his world becomes forever locked in history. This may discomfit his widow—who was also raised in complicated circumstances on an emotionally restrained, class-ridden island—but it is nevertheless the case.

One cannot make sense of Lennon’s ability to encompass opposites (the political activist who didn’t vote until 1968, or the pop genius who thought The Beatles should put out “Revolution #9” as a single, or the devoted househusband who smacked Yoko and yelled in Sean’s ear so loud they had to take him to the ER), none of this makes sense without investigating his psychology. That is, his childhood. As the Jesuits say (or was it the Hitler Youth?), “Give me the child until seven, and I will give you the man.”

American writers on Lennon, drenched as they are in our culture of TMI, generally do better at getting inside his head. Albert Goldman’s Lennon is a tormented demon, but also someone with the ruthlessness, self-preservation, and drive that it took to make The Beatles happen, and then survive once they had. Unfortunately, Goldman lacks sympathy towards his subject, and so in the end his Lennon remains a puppet, or at best, a cartoon. It takes compassion to delve into someone’s mental state. (That’s why therapists rarely punch their patients.)

Something British, That Feels American

Sympathetic but unflinching, Nowhere Boy is a very British attempt at Lennon that feels very American, and because it pulls off this balance, it will give Beatle fans a really precious gift: a “John Lennon” that actually makes sense. The screenplay was written by Matt Greenhalgh who wrote the Ian Curtis biopic Control. The details of Northern life in the straightened 40s and 50s are sketched flavorfully but not overstated. For a special occasion, Julia makes vanilla buns; she serves exactly four of them, each no bigger than a half-dollar, one for each child plus herself. Message received: sugar rationing ended in ’53, but three years later, money’s still tight. In Nowhere Boy, houses are dark, and small. People walk, or bike, or ride the bus. Clothes are wool. It’s no wonder Lennon’s generation idolized America, and once they’d conquered the world, made the Sixties happen as they did. What is Swinging London but the reverse of Liverpool ten years’ before?

Nowhere Boy’s version of John and Paul rock out as The Quarrymen. Amazingly, it works.

There were certain aspects of the film that rang a bit false. The Oedipal nature of John and Julia’s relationship is, uh, right out there in a way that seemed like a convenience of the screenplay. The mother-as-lover meme was encouraged by John’s late-70s tape describing how he wanted to feel his mother’s tit, and that she probably would’ve let him. But Lennon also remarked on many occasions about how physically repressed his upbringing was, how it took until the 70s for him to realize “touching is good.” (This from a man who had more groupies than I’ve had hot dinners.) All of this is to say, the scenes where John and Julia were cuddly seemed like a sop to the modern sensibility.

So too the blue language, which to the modern ear is necessary to connote “teenage rebel.” Rebellious teenagers circa 1956 Liverpool were different than ours today; next time you watch Rebel Without a Cause, for example, notice how well-behaved all the kids seem. One of the most profound legacies of The Beatles generation was a great opening-up, emotionally speaking—a shift from reserve and repression to extroversion and sharing so decisive that now, anything but that strikes us as unreal. Nowhere Boy’s Lennon uses the f-word with Mimi, and I don’t think that happened in 1957. In fact, I don’t think the 40-year-old Lennon would’ve sworn at Mimi. That’s not the kind of man he was, and forgetting that turns him into one of us—ie, a creature of the world he helped create. That’s incorrect. As a boy, John Lennon hated school, but as a man, he slept with a picture of Quarrybank over his bed. His last New Year’s Eve, he wore his old Quarrybank tie; one, he still had it, and two, he liked it. Avatar of the new era, Lennon was quite literally old-school, and we should remember that.

Mimi, too, is made to “come around” regarding John’s choice of career in a way that, while it makes her more appealing to modern audiences, isn’t really supported by the historical record. In Nowhere Boy, for example, she’s seen smiling approvingly at John during the famous Woolton fete, when in reality she “watched [John] cavorting around… I wasn’t amused…I wanted to pull him offstage by his ear.” (Thanks @thedailybeatle.) By making Mimi support Lennon’s music, the movie avoids that eternal Beatlefan question, “Why the heck does he love her?”

That I found myself expecting this degree of accuracy is a credit to the overall verisimilitude of Nowhere Boy. I saw the care they took with it, and you will, too, so even if you don’t like it as much as I did, you’ll admire the movie as something worthy of the real people it is based upon. I was genuinely moved during the scene when all the family laundry is aired, once and for all.

A Mid-Atlantic Man

A Liverpudlian transplanted to New York, by the time he died, John Lennon was a Mid-Atlantic Man. He is the patron saint of the coming together of British and American culture which started with The Beatles and has gathered steam ever since. From where I’m sitting, I could get a Cadbury Flake bar in five minutes. I’d pay for it with money I made transforming a very British children’s book in a very American way. Your life might not be as Mid-Atlantic as mine, but you can certainly flip on BBC America—or if you’re in the UK, buy a Snickers bar, or watch “30 Rock” on Hulu. Nowhere Boy embraces this cultural melding, which is probably why it feels so accurate. John Lennon could get a Flake bar five minutes from where he lived. And he’d pay for it using money he made transforming a very American music in a very English way.

I was visiting Oxford the night Diana was killed, and for the week after that. The way people mourned, what they did and said, and the way the mass-media shaped all of it (from the wall-to-wall TV coverage to Elton John singing “Candle in the Wind”) struck me as, well, American. I didn’t expect British people to leave stuffed animals and say they felt as if they knew her personally; and I doubt anybody older than John Lennon’s era would’ve said that. American emotionality and egalitarianism is new in UK culture, and John Lennon did as much as anyone to create that. In 1980, when John Lennon died, Britain and America mourned differently; in 1997, they really didn’t.

Whatever one thinks about this change—whether it’s a good thing, a bad one, or somewhere in between—it allowed Nowhere Boy to succeed in a new way. The movie feels both thoroughly British, and emotionally aware. It gets both the facts and the feelings 99% right. That’s a great thing, and augurs very well for future Beatle media. YOU GOTTA SEE IT.

Thank you for the review. Hey Dullblog is the sole publication in the entire world whose positive review about a film like this I would even consider trusting.

You’re welcome, Alexander. Please keep in mind that YMMV–as I said, the mind recoils at the idea of Nowhere Boy, and that may be too much for you. But I was able to get over it. I’m looking forward to seeing it again, and I don’t really do that with movies.

Tell us what you thought, eh?

I really enjoyed reading this.

Ah, you’re just buttering me up so I’ll buy you guys a drink on the veranda at The Georgian. (BTW, floors 4 and 5 are supposedly haunted–if you believe in such stuff.)

The best thing I read all day. Great post, Mike…

Wow, guys! Thanks!

Thank you for this post. But I gotta know…were Mimi’s cats featured in the film?

I didn’t see ’em, ssspune, but you know cats–they hide.

As a life-long Lennon nerd, I loved the film and loved reading your thoughts on it. To me, it’s the first Beatles-themed movie with any actual cinematic quality.

I don’t know if you ever read the original screenplay (or at least the version that I found on the internet a couple of months before the UK release), but I think it delved deeper into the John-Mimi relationship than the final version. Sam Taylor-Wood once described the film as the story of a love triangle, but it really sort of ends up being more about John and Julia… which I think is a bit of a shame, because Mimi was just as important an influence on him. She had been, after all, his intellectual sparring partner and the symbol of most things that he was at once drawn to and rebelling against.

The screenplay I read opened with Mimi’s famous—and some say, fabled—mad dash through the streets of a bombarded Liverpool on the evening of October 9, 1940, thereby fixing in the viewer’s mind the special life-long bond between the two. The next scene showed a 5 year-old John struggling to keep up with his Auntie Mimi and Uncle George as they both held him by the hand on their way to St. Peter’s Church one Sunday morning. That particular image, I believe, would have added color and depth to the nature of young John’s early upbringing and would have set the stage even more clearly for his devastation at George’s sudden death.

Have you ever seen on YouTube the BBC interview with Mimi that took place in 1981? One of my favorite Beatles-related moments happens near the end of the interview, when Mimi’s quintessentially pre-War generation English stiff upper lip quivers for just a moment, her eyes go into a far-off glance, and she says, “And, honestly, if I thought he was dead, I don’t think I could go on. I don’t think of him as dead.”

Mimi must have lived in terror at the thought of losing John to Julia. “Nowhere Boy” does portray that fear somewhat, but I think the Mimi-John-Julia triangle played a larger role in the young Lennon’s psyche than the final version of the film lets on.

And we all shine on…

I saw the film some time ago in the UK and agree it is very good; I’ve commented on it at length here:

http://sweetwordsofpismotality.blogspot.com/2010/05/nowhere-boy.html

Some points made: Macca saw an early script and complained about the characterisation of Mimi, referred to as “a cruel woman”, which did not accord with his idea of her “tough love treatment” of John; Taylor-Wood had the character rewritten.

Also film critic Philip French says that the fifties-set British film That’ll Be the Day, about a disaffected boy’s discovery of fock’n’roll, was based in part on Lennon – and there is certainly a mother, wonderfully played by Rosemary Leach, who has more than touch of the Aunt Mimis about her. (This is made especially credible when you know that Neil Aspinall was involved in the music and Ringo co-starred.)

Finally, one point about Nowhere Boy perhaps less obvious to American dullblog readers is the issue of accent. The director wasn’t going for a “lookey-likey” actor, which is fine (and Ian Hart’s too old now anyway), but A Liverpudlian critic wrote in a UK paper that the lead couldn’t quite get “the sardonic nasal twang that seems to carry so much of Lennon’s personality in it and set him apart even from the other Beatles (he was a few notches up the social scale).” In other words, the film, good as it is, really does make him more of a Working Class Hero than he was; “cruel” Mimi would not have been too happy about that.

Super comment, Tony. And point well taken about Lennon’s accent; the intricacies of his social class are something I avoid because, as an American from the Midwest, I suspect I haven’t a clue how to decode them.

That’s one thing I remember liking about Norman’s Lennon bio: how he brought up the class differences between Lennon and the other Beatles–and Mimi’s treatment of Paul and George as distinctive of them.

Thanks for that, Michael.

If it hasn’t been noted already, could I draw this blog’s attention to a current British TV comedy sketch show, Harry and Paul? It has a regular sketch based on a very simple premise: the Beatles are still together, still recording, didn’t take drugs, are still with their first wives.

Oh, and didn’t die. There’s a youtube link to one of the best of the sketches here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SplT4tv9vVk

It’s funny but sort of heartbreaking too: they are now grey-haired moptops, jolly schoolboys bantering with each other as though they’re still in Hard Day’s Night (the writer gets the style just right), kept in order by a Norman Rossington figure. The song parody isn’t bad either – maybe not up to Rutles stand but serviceable. It’s heartbreaking because you know the ridiculousness and the impossibility of the situation and yet part of you wants it to be true. There’s a song in each sketch and this one has the lyric:

I loved you when you were seventeen but you walked out my door

But you soon came rolling back to me and now you’re seventy four

I love you more, more, more …

Which may not be up to Innes’s standard but it becomes affecting when “the wives” burst into their hotel room and you see John embracing Cynthia, Paul with Jane, George with Pattie – though in a wonderful touch Ringo is married to Cilla …

Try it, as I think it may be tailormade for the readership of this blog.

Watched this on Netflix not long ago. I agree with Mr. Gerber, it’s probably the best “Beatle biopic” that’s been made up to this point. They did take a lot of care with this film. Superb cast! Great acting. Although, it doesn’t cost much to get a pair of brown contact lenses for the lead actor. I think that would have gone a long way in making him look more like John. But that’s just a minor quibble in what was otherwise a spot on portrayal. The guy who played Paul also did a fantastic job. He kind of put the “badass” John in his place at one point, which was funny and kind of how their relationship worked. Both actors showed their characters’ complexity. Lot of poignant moments in the film, including the scenes with Mimi and Julia. If this weren’t about real life people, it still would have been a good movie.