- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

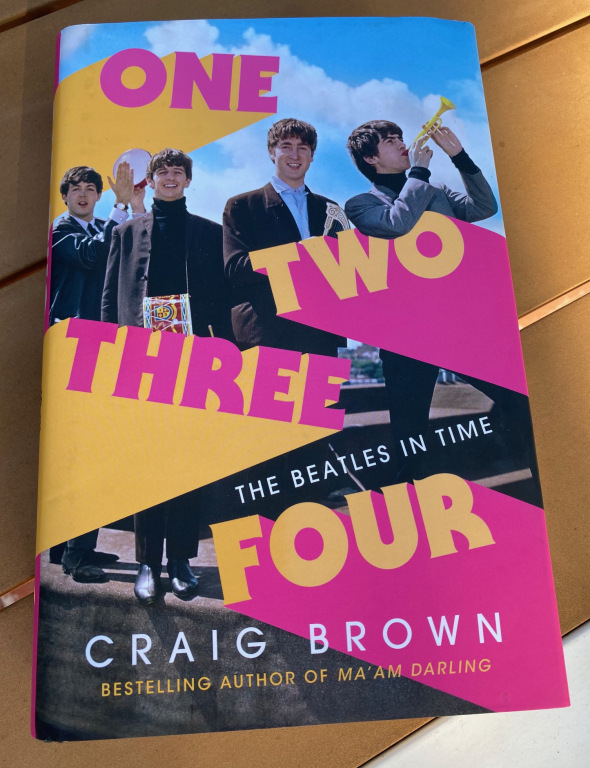

Is it possible to write anything fresh and interesting about the Beatles in 2020? Improbably, Craig Brown has managed to pull off this feat in One Two Three Four: The Beatles In Time.

It helps enormously that Brown departs from the marching-in-strict-chronological order structure used, understandably enough, in many accounts of the band. Brown is the author of 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret, as well as multiple parodies, and he brings a light (but not lightweight) touch to the proceedings. He’s willing to go down rabbit holes after interesting tidbits, to summarize long-drawn-out situations simply, and to share his own investment in what he’s discussing.

Brown’s writing and organizational style stands in particular contrast to that of Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In: The Beatles All These Years. God knows I’m grateful to Mr. Lewisohn for his indefatigable research and his readiness to detail pretty well everything that can be known about the band. But I also have to confess that I glazed over and found myself skimming through parts of his book. Lewisohn is not a sparkling stylist, and there is a dogged stateliness to his progress through “all these years.” In fairness to him, I have to admit that I’m at a point where the Beatles story is far from new to me, and that may well color my perception of any new book about them.

So I was skeptical when I picked up Brown’s book. He won me over on page 1, with his brief account of Brian Epstein and Alistair Taylor going to see the Beatles at the Cavern for the first time. The scene concludes:

“After the show, Taylor says, ‘They’re just AWFUL.’

They ARE awful,’ agrees Brian. ‘But I also think they’re fabulous. Let’s just go and say hello.’

George is the first of the Beatles to spot the man from the record shop approaching.

‘Hello there,’ he says. ‘What brings Mr. Epstein here?'”

And we’re off — we seem to be there with the people described (note the use of the present tense in that excerpt), waiting to see what will come of this encounter.

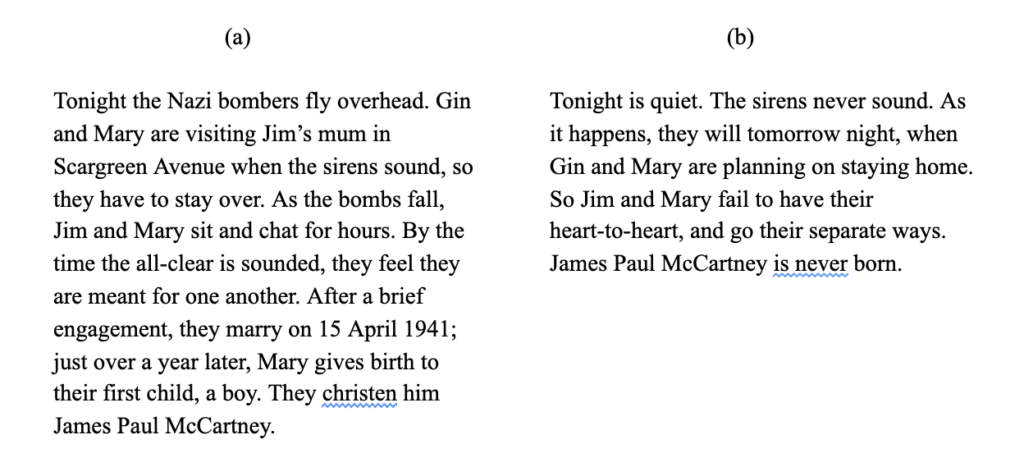

It’s that sense of openness, that recognition of multiple possibilities and the great unlikeliness of the Beatles’ success, that I found especially refreshing. At a few points Brown uses side-by-side narratives to emphasize what might have happened instead. Here he does it as part of an account of one evening in “Late November 1940”:

The greatest use of this split-screen effect in the book is Brown’s three-column breakdown of how the myriad people who have gone on record about Lennon’s assault on Bob Wooler at McCartney’s 21st birthday party have described it. (He also includes three statements by Lennon himself, given at separate times.) Seeing how differently everyone from Tony Bramwell to Philip Norman has detailed the assault and the extent of the injuries Wooler suffered illustrates more powerfully than a lengthy account could the reality that all history is interpretation.

Brown possesses an almost Wildean way with trenchant characterizations, for example: “Those of [Alex] Mardas’s ideas that worked were not his own, and those that were his own failed to work” and “Albert Goldman, the most merciless and hyperbolic of all John’s biographers.” Brown unerringly picks the best quotes too, as when he notes Alistair Taylor’s remark that Allen Klein had “the charm of a broken lavatory seat.”

Brown’s great with lists and footnotes as well. Here’s an itemization that reveals much about the chaos of the Apple Corps offices: “Visitors and employees alike walked off with all sorts of stuff: televisions, electric typewriters, speakers, cases of wine, fan heaters. One employee removed the lead from the roof on a daily basis, soon creating leaks that caused thousands of pounds’ worth of damage.”

And here’s Brown’s footnote to Peter Brown’s “unfeasibly vivid picture” of Lennon’s supposed sexual encounter with Epstein in Spain: “The memoirs of former Beatles office staff share this strange quality of divine omniscience with the memoirs of royal housekeepers and valets.”

Brown’s humor is in line with the Beatles’ own, a big reason why this book is so enjoyable. One Two Three Four includes the best account of Lennon’s punning sensibility I’ve read, and Brown’s descriptions of some of the contemporary Beatles-themed tours he’s gone on are not only revealing but intermittently hilarious. But he also captures the darkness of the story. Juxtaposing an early publicity photo of the Beatles with a candid snapshot taken during the late studio period, Brown notes: “The Beatles had aged with an almost macabre rapidity. In the five years from 1964 to 1969 they matured at a rate of knots, not only in the range and depth of their music, but also physically.”

One last note: Brown’s explorations of people on the edges of the Beatles story are extraordinarily revealing; some achieve a kind of “Eleanor Rigby” quality, as they recount what happened to those left in the Beatles’ wake. There’s Pete Best, of course. But who thinks of Jimmy Nichol, the drummer who subbed briefly for Ringo during the 1964 tour of Australia? His experience with fame seems to have blighted his life: though his former band held his position open, he came back from the tour determined to become a star and started his own band, which failed and marked the beginning of a long, sour decline. Then there is Detective Sergeant Norman “Nobby” Pilcher, the tireless enforcer of drug laws against 1960s musicians, eventually imprisoned for perjury and conspiracy to pervert the course of justice. However, the most moving portrait in the book is that of Brian Epstein; fittingly, the book both begins and ends with him. His centrality to the Beatles’ story has never, to my mind, been presented so clearly or compassionately.

In short: One Two Three Four is well worth your time, even if the stack of Beatles-related books you’ve read would reach to your head or higher if stacked up on the floor.

Is there any McLennon in the book?

.

Short and to the point. I like it.

Off topic, but the Recent Comments feature here seems to be borked.

Thanks, Sam. Not sure what is going on — seems to be a WordPress thing. I’ll see what I (or someone who knows more than I do) can do about it.

Brown is a true master of the pithy remark.

Not as such, Gretchen. I thought Brown did a good job dealing with the complexities of the Lennon/McCartney relationship overall, though. And I found his take on Brian Epstein really illuminating and humane, as I mentioned. This book gave me the best sense of Epstein as a person that I’ve gotten from anywhere.

Thanks for the review Nancy! I think I will read it.

Just wanted to add that I appreciate Mark Lewisohn, because “Tune In”, while maybe not exciting, is factual, and meticulously researched. There has been plenty of salacious crap written, some true, some false, but Lewisohn is trying to be completely factual. I want the truth, not rumors.

@Nancy, thanks for the review! I have that one on my list. Since there’s no e-book and I do have the not-quite-six-foot stack of hardcopy Beatles books yet to read, it’s out of my price range for now, but maybe they will release an e-version. I definitely like a little wry humor in my Beatles reading now and then — see Ray Connolly– so this sounds like a good ‘un. I look forward to reading it.

.

I’m currently reading Martin Shough’s “Truant Boy: Art, Authenticity, and Paul McCartney” and WOW. It’s a look at Paul McCartney’s oeuvre through the lens of art and music history, current events at the time he wrote his songs, and through contemporary criticism. Shough makes a lot of references that are esoteric to me, and I have spent a lot of time looking up his references (I never knew about Lisztomania! What a trip) and even consulting the dictionary now and then to decipher his fifty-dollar words — and I considered myself to have a pretty strong vocabulary. 🙂

.

Admittedly it is a blatant defense of McCartney and compares him to artists in many genres of creation. It does make comparisons between John and Paul’s work, not always to the detriment of John, though Shough does seem to have some suspicion of John’s solo career aspirations and lyrics, but most definitely pointed at the unfair comparisons in music criticism between the two. And for those who might say that nobody really disrespects Paul in media criticism circles anymore, Shough provides plenty of references to articles, some pretty recent, that do just that. I guess it makes me feel that I’m not crazy when I read anti-Paul bias in so many books written even recently. I’m looking at you, Tim Riley and Mark Lewisohn. Anyway, I’m only a quarter of the way through and have at least ten times now wanted to toss my e-reader in the air and let it float away on a cloud of “THIS.”

.

For example, Shough has been discussing criticism of Paul’s lyrics as lightweight or whatever, and this passage jumped out at me because of recent mentions of How Do You Sleep and I Know (I Know) here on HD:

“McCartney is perfectly capable of banal, awkward, or just plain ‘huh?’ lyrics. The same can be said of Lennon. The point is that when a commonplace lyric effect occurs in a McCartney song it can become an opportunity for a disproportionate contempt which is almost hysterical in tone. Such an unreasonable prejudice needs explaining.

.

The permission we (some of us) give ourselves to sneer at McCartney surely borrows some of its sanction from Lennon’s public example (e.g., How Do You Sleep?) during the tension of their ‘divorce.’ Lennon himself recognised this and regretted it. ‘The years have passed so quickly,’ he wrote in I know (I know) in1973, ‘and I know now what I have done,’ elliptically referencing McCartney songs in the lines ‘Today I love you more than yesterday’ and ‘I know it’s getting better all the time,’ set to music which is an unmistakable homage to I’ve Got A Feeling, the last truly joint Lennon & McCartney track to be released …”

.

So, er, “THIS.”

@Kristy: wow, thanks for the Truant Boy book rec, that sounds awesome. Goin in the wishlist pronto.

.

a disproportionate contempt which is almost hysterical in tone. Such an unreasonable prejudice needs explaining.

.

Sounds very promising. Enjoying the use of “hysterical” as a descriptor, as Paul’s detractors’ criticisms are so often couched in sexist language. (See Michael G’s immortal “just say Paul has girl cooties and be done with it” takedown of such critics.)

Wow thanks for the review. I will read it for the writing style. It sounds great.

@Kristy: “It does make comparisons between John and Paul’s work, not always to the detriment of John”

.

Not always, but most of the time? Hard pass. Do we really need another In Defense of Paul book? I thought Many Years from Now and Conversations with McCartney provided enough already. Will we ever see the day when John and Paul are not held up as great artists at the expense of the other? The fact that this is done ad nauseam is a testament to the fact that neither was as good on their own as they were as a team. Therefore, the answer is probably not.

Hah, that’s why I put the content notification in there, for John fans sensitive to possible critique. There are a few here on HD. 😀 The book doesn’t slam John SO FAR, but in direct comparisons between the two (i.e., their “ireland” songs, and their holiday songs) shows how when it comes to banality, John gets a pass whereas Paul gets derision. I mean, I don’t wanna see Paul glorified at John’s expense or a whole book of “hur hur John” jokes or jibes like I’ve read about Paul in several John books. Because they were friends and a team. But while this book hasn’t pushed those buttons for me personally, it surely won’t be everyone’s cup of tea.

.

But IMO, right now? Gimme all the Paul-is-awesome books. I mean, half the Paul biographies I’ve read were written by some dude who clearly didn’t care about Paul at all. Maybe someday we could start from equal ground and examine everyone on their own merits and without the historical spin. (All my opinion based off my own experiences in fandom, of course.) I’d love it if every book treated them as equals and complements — maybe the Craig Brown book Nancy is reviewing does? — but unfortunately we’re not there yet. Equity before meritocracy, as a friend of mine always says.

I read Truant Boy and thought it was very good and I remember that passage you quoted and was also like “Yes this” when I read it. 🙂

Particularly with regards to his lyrics and his overall creativity. Like you mention, it doesn’t help when half his biographies are written by people just looking to make a buck rather than people who are actually interested in their subject and so just repeat the same old stuff with the same old “yeah I didn’t give this much thought” interpretations. No not everything he wrote lyrically was profound but plenty of what John and George wrote were pretty banal as well. The bias comes in that when John writes so called “nonsense” many immediately look for “deep meaning” because hey it’s John he’s deep, right? Whereas with Paul they just assume it really is nonsense. ”

Like if John wrote Monkberry Moon Delight my person opinion is that many would immediately note the surreal nightmarish imagery of the lyrics and how they related to events that were going on around the time they were written(this was around when all the lawsuits were going on, the end of the Beatles, etc). It’s that Paul’s lyrics tend to be nitpicked over and the tiniest weaknesses often exaggerated because they are assumed to be weak and meaningless and John’s are assumed to meaningful so a weak word choice or repetition is often given a pass or at least not mentioned. I read a great joint research paper done by these three professors, at different universities in different countries, which did a study of the language of John, Paul and George’s lyrics while in the Beatles, with charts and everything, so it was as scientific as something involving words could be. LOL Unfortunately I had the link saved in a “Notes” program and that program stopped working so I can’t open them anymore. Hopefully I’ll come across it again some day, it was interesting.

As Christmas songs go, I prefer Wonderful Christmas Time. Happy Xmas(War is Over) is okay but mainly I find it dirgelike and cloying, not that Xmas songs need to be upbeat(Silent Night isn’t exactly a party ). So I’d rather have something like Wonderful Christmas Time stuck in my head, because IMO it’s more interesting musically. I’m not saying it’s some sort of epic classic but it just has more interesting things going on musically.

I do think Lady Madonna is probably not quite as straight a lift as Stewball is, I mean Stewball is pretty much the same music, just with different lyrics, I think Lady Madonna is more “in the style of Bad Penny Blues”, which isn’t to say it’s not pretty obvious where the influence came from. Xmas is sort of the opposite of Golden Slumbers, Paul had the lyrics from the book but didn’t know the music so he made up his own music, Xmas uses most of the music and makes up new words. 🙂

“A.k.a. “Happy Stewball (War Is Over)” ;)… ” Maybe someone could do a mashup? LOL

many would immediately note the surreal nightmarish imagery of the lyrics and how they related to events that were going on around the time they were written

.

Thank you! So often I’m boggled by the amount of shade thrown at Paul’s “surreal” lyrics. MMD is a perfect example. “My hair is a tangled Beretta”; “rattle of rats had awoken the sinews, the nerves, and the veins”; “I stood with a knot in my stomach”; “that terrible sight: two youngsters concealed in a barrel” etc….like….what is unclear, here, about the emotional tone of the song? It’s anguished words, with a monsterish vocal, culminating in the sung equivalent of a seizure. Now, what is it about, specifically? I dunno; does there have to be a 1:1 symbol/symbolized ratio in every song? (If so, can I please see the cheat sheet for “I Am the Walrus”?) Some ideas: the toxic fame/drugs/power cocktail; isolation; disillusionment; reaching your breaking point; identity crisis; all the above? I don’t understand how this is not an immediately obvious first reading. Where are these writers getting their MFAs??

.

Is it the little moments of cutesiness Paul tends to inject? Like, if the line had been “concealed in a a barrel sucking yellow matter custard from a dead dog’s eye” maybe critics would’ve gotten it? But for my money, those little dashes of rainbow glitter make it all the creepier… like an evil one-eyed cabbage patch doll or something. Because certainly part of the nightmare, for the narrator, is an intermittent awareness of his own disintegration.

.

a great joint research paper done by these three professors, at different universities in different countries, which did a study of the language of John, Paul and George’s lyrics while in the Beatles, with charts and everything — Oh my god, MG, I need that in my life.

.

I’m not saying Paul never gets lazy with his lyrics–he does! But think about it: if he was capable of momentous lyrics for every single one of the eight billion melodies that just waft to him in the breeze, he’d be loooong gone by now anyway, astral projected into the 7th Level or whatever. He’d be a Shakespeare or a Da Vinci. I’m okay with him not being that.

“Some ideas: the toxic fame/drugs/power cocktail; isolation; disillusionment; reaching your breaking point; identity crisis; all the above? I don’t understand how this is not an immediately obvious first reading. Where are these writers getting their MFAs??”

Annie, right? I think “all of the above”, but maybe particularly isolation, disillusionment, reaching your breaking point and identity crisis–but the fame issue does exacerbate all that. He was going through all that either at that time or just prior to it. As you say why does there need to be a 1:1 ratio of meaning where every line needs to correspond directly to a specific incident or person? Paul creates a consistent mood throughout the song that takes a journey through an anguished nightmare. Some of the imagery and word choice is because it’s unsettling, or sets a particular mood. No there was no piano up his nose there are different meanings to that – it can mean something is very close by(so close it’s practically up one’s nose), it can be a way to take drugs.The meaning itself is likely in between the two, it’s not meant to be literal obviously. There is a lot of musical imagery – the piano is outspoken, the wind plays a “dreadful cantata” – it seems like the piano is attempting to be heard over the cantata coming from outside. Thinking about in context of the Beatles break up, all the negativity, the lawsuits, it’s a very cool but troubling song. Honestly it makes me feel a lot for what Paul was going through at the time.

Part of it might be that there is a lack of understanding of Paul’s interest in the surreal, which was deep and abiding interest for him both in art and literature. So rather than thinking “surreal” , the critics, who had been primed to thing of Paul as lazy and lightweight and were pissed off at him for “breaking up the Beatles” so weren’t inclined to look any further and the whole lyrical thing stuck with him.

I too think the little bits of levity and brightness often make some of Paul’s stuff even more eerie and creepy. Like Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, a happy little tune about a serial killer! LOL But it definitely has some interesting insights. Maxwell even has serial killed fangirls, certainly one of the more disturbing trends with regards to such things(Rose and Valerie:).

Whoa, @MG, our comments are back!! I’m so glad because I remembered we were having a good time, but forgot where exactly we left off the conversation. 🙂

.

No there was no piano up his nose there are different meanings to that – it can mean something is very close by(so close it’s practically up one’s nose), it can be a way to take drugs.The meaning itself is likely in between the two, it’s not meant to be literal obviously.

.

Exactly. My very first reaction to the image is simply, “Ouch.” Makes my nose tingle a little in sympathy, you know? Like, he’s using the piano as a weapon/shield against the “dreadful cantata” but there’s also an element of the piano being burdensome/painful. Which fits in with the line about his hair being a Beretta: long hair was a HUGE part of the Beatles’ identity. Now it’s a gun to his head. (Magritte should have painted a portrait of someone with a tangled Beretta for hair. Just sayin.)

.

I too think the little bits of levity and brightness often make some of Paul’s stuff even more eerie and creepy

.

Ditto with the bits of levity injected into his torch songs. I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen his “Oh! Darling” vocal, for example, dismissed as phony because some of the little interjections (the ooh-woos and “believe me darlin'”) sound affected. But the thing is, people do that! That’s a normal thing to do in emotionally fraught moments — inject a little irony, a little humor, a little “haha, aren’t I embarrassing myself……no but really, this is really how I feel.” (I’m reminded of Alistair Taylor’s report of Paul sobbing on his shoulder after the breakup with Jane, and then joking “People think Jane’s the drama queen, but it’s me!”)

.

It’s another case of Paul not being met on his own terms. John Lennon was indeed a master of taking a painful emotion and ramming it home, no pretense or hesitation whatsoever — and that’s awesome! That’s a very special quality for an artist! That Paul communicates pain in a different way doesn’t make him phony.

Annie, there’s a good chance that “biretta” in “Monkberry Moon Delight” isn’t a gun, but a specific type of hat. Would make more sense with the line “my hair is a tangled biretta.”

.

From Wikipedia: “The biretta (Latin: biretum, birretum) is a square cap with three or four peaks or horns, sometimes surmounted by a tuft. Traditionally the three-peaked biretta is worn by Roman Catholic clergy and some Anglican and Lutheran clergy.”

@Nany Carr: Yeah, the „baretta“ was always just a hat to me , maybe because it is more commonly used here as a term for the kind of flat woolen cap soldiers wear when not in combat ( i.e instead of a helmet) , and it basically looks like the cap worn by French men ( well in adverts for French cheese, they still do). There are photos of the Beatles in France wearing them. Or think about Prince´s Raspberry Beret! So it is simply his hair, which was very tangled during those Scotland years…

@Kristy, I totally agree about the Paul biographies. Most of them are by people obviously just in for a quick buck.

.

I downloaded the Craig Brown book at the beginning of the pandemic, because I read one or two excerpts on a newspaper site, which I found promising. Well…. it is not bad, but I felt his style got tiring after a while, and yes, again, it is very Johnandyoko centric. In the end I got the impression he had a number of old articles and coupled them with his recent visit to the Beatles sites in Liverpool, making fun of the fandom industry ( with justification, but he is of course also part of it). Must check again about the Brian Epstein part though.

So with John it’s “critique” but with Paul it’s anti-Paul bias. Gotcha. Yeah, there a few John fans here, exactly a few. Me and some McLennon girl. That’s sad. Wut? Happy Xmas pwns Wonderful Christmastime. Blech.

“So with John it’s “critique” but with Paul it’s anti-Paul bias. Gotcha.”

.

There is a difference in tone between critique and bias, as most people who can read things critically will understand. I have attempted to reply in good faith regarding what the book is about. If every effort I make will be met with derision, then just avoid the book, for heaven’s sake.

.

@Jesse — I couldn’t find an e-book! On Amazon, at least. I’ll keep an eye out. Thanks for further thoughts.

@Kristy, I got mine from amazon, but I am in Germany… don’t know why they do not make it available as an ebook in the US.

I liked “Happy Xmas” the first time I heard it…when it was called “Stewball.” 😉

A.k.a. “Happy Stewball (War Is Over)” ;)… A very nice song about a racehorse.

I wasn’t around in 1956 to hear “Lady Madonna” for the first time, aka “Bad Penny Blues”. So what, folk songs and traditional songs are fair game, ask any folk artist. My point is, getting a root canal is preferable to having the refrain from “Wonderful Christmastime” stuck in my head.

I’ve just started the audiobook, and while it seems worth a listen, I got thrown into anger by a couple of incredible silly mistakes – calling Nems “north east music stores”, for example. I would’ve thought there are certain facts that no one ever makes mistakes on. I might be being too hard on the author though…

Nancy, belated thanks for this review! I bought the book on the strength of your recommendation and am really enjoying it. Brown does an excellent job of helping me, a Millennial, get a better understanding of what Beatlemania must have been like than any other author I’ve read. Most everyone else describes it as a tiring triumph; Brown shows it as being bizarre, frightening, silly, and traumatic. I feel as if I’m just now understanding a key part of why the Beatles circa 64 seem like people one might actually know, but by 68, they’re not.

.

Brown is also very good on how Beatles history is a series of authorial choices based on imperfect memories. Every other book simply reports their preferred version of events as true, so this is refreshing. My only note is that he gives Goldman short shrift at times—yes, Goldman was hyperbolic and had an axe to grind, but Brown glosses over the fact that Goldman’s version of the Wooler incident is the only one supported by a statement from Lennon himself, in 1980 (“I realized I could kill him”). That tension in Goldman between accuracy and hyperbole is important in trying to separate truth from untruth in the Beatles story.

I find Goldman’s animus to be a feature, not a bug. Goldman’s intent is so clear (he’s writing a hit-job), and his opinions regarding all the major players stated clearly and incessantly. So you can tune him down/out, and look for anything that is surprising.

.

What is much more challenging, in my opinion, is a writer like Philip Norman, who has a very lucid style and seems even-handed…until you get to the end of the book and think, “So I guess George and Ringo really didn’t add much to the group.” That’s a much harder bias to confront, because it’s bias by omission and shading. With Goldman, if you don’t agree that Lennon was a drug-addled no-talent who hated himself and everybody else, you’re already thinking for yourself. Fans read Goldman adversarially–and that’s a good thing.

My immediately obvious first reading of Monkberry Moon Delight is that it’s about sex. The fact that Paul was quoted as saying it’s about a fantasy milkshake does nothing to diminish that opinion. That being said, I can’t help but wonder if it was a self-conscious attempt at John-style nonsense lyrics, or a mocking of John (Twist and Shout singing and all). I’m not sure which, perhaps both. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the working title was Strawberry Moon Delight. I have to agree it’s nightmarish.

.

I think if you asked Paul he would say that John was the better lyricist, although Paul certainly has his moments. I Am the Walrus may have nonsense lyrics, but John had a way with the turn of phrase that lends them an interesting and witty dimension. ‘Sitting in an English garden waiting for the sun/if the sun don’t come you get your tan from standing in the English rain.’ That’s brilliant and it makes perfect sense to me. It’s not every day that you find lyrics that are seriously catchy. Come Together, though one of my least favorite songs of John’s, has lyrics that make their way into one’s memory and never leave. There is a commercial that has people walking around various city streets while taking turns reciting the lyrics, smiling all the way. John had to encourage Paul in his lyric writing because he didn’t think it was worth the effort. John in the early days also didn’t put a lot of value on lyrics and he cranked out the pop hits like a craftsman. In recent years, as Paul has paid a lot more attention to the lyrical side of songwriting (Chaos and Creation being one example), he’s gotten nothing but glowing reviews from critics. It’s not bias. This narrative is so… yesterday.

Oh, don’t get me wrong, I ADORE Walrus! And think it’s a superior song, not least because of John’s brilliant vocal and the brilliant arrangement/production. Up there in my Beatles top 15, probably. “Come Together” is also wonderful, and I will die on the “each verse is about a different Beatle” hill. I would also absolutely agree that John is a more consistently good lyricist, tho imo Paul’s best are as good as John’s best. Plus Paul’s resonate far more with me personally. My beef is with the wide scale dismissal of Paul’s surreal stuff as “nonsense” which shed no light on the author and are therefore not worth unpacking. And I believe John when he says “Paul is a capable lyricist who doesn’t think he is, so he would avoid the problem”. (In another interview John says “Paul was always a bit coy about his bass playing, tho he’s an egomaniac about everything else” which always makes me laugh because it’s like, you can’t have it both ways. Paul can’t be insecure about 2 of the 4 of his top musical contributions to the band, AND a blanket egomaniac. I know, I know, John was mercurial and insecure himself and had that weird “If I feel weak, that must mean Paul feels strong” black and white mindset. But it does make me chuckle.)

.

Sex, eh? Because of the banana line? That particular line might be, but as a glimpse into the psyche of an anguished person teetering on the brink, it would make sense that sexual insecurities would be a factor, tho not the overriding theme imo.

.

Yeah, the “milkshake” thing is a classic case of Paul giving the very first, embryonic inspiration for the song and then saying nothing about what the song truly became. À la “Lady Madonna”, “Wanderlust”, “Little Lamb Dragonfly”, etc. So it’s up to us to dig a little deeper! Which is fun. 🙂

I don’t particularly get sexual from hose or sucking or the milkshake idea. LOL I don’t think milkshake was used in that way back then. Hose, I’m not sure where there is a sexual context in that(I mean I can think of one as a slang term for a body part but I don’t think it fits the way it’s used in the song and I’m quite sure there are uses for hoses in all manner of um…things:)). I think it’s a metaphor for taking an emotional beating/critical beating – the choice of words being based on the rhyme, hose rhymes with nose “sore was I from the crack of the enemies hose” rather than whip or belt or something like that and it also adds to the surreal “world” of the lyrics.

Even the tomato line fits in with that idea. There’s a reason the movie review aggregation site is called “Rotten Tomatoes” after all. 🙂 The old sort of vaudevillian visual for a “bad review” was showing an entertainer having rotten tomatoes thrown at them. I think that’s related to the ketchup, soup and puree in the refrains, what do you make out of squashed tomatoes? So I can see how Paul’s mind would have made the connection – maybe it’s the song’s version of “if life gives you lemons, make lemonade”, if life gives you tomatoes…., as well as well as ketchup being a play on “Catch up….don’t get left behind”. I think it’s actually a pretty complex song both in it’s poetry and potential meaning. Yes Paul could be a lazy writer but I think his best stuff, of which there is quite a bit, stands up to anyone’s, certainly to John’s best stuff–Paul could come up with complicated and intense poetic schemes.

Sucking I think was really just the better word choice for the description of what was being done in the barrel – sipping isn’t really the right word in that context. He’s going for something more disturbing, even though on the surface why would it be disturbing? The word sucking is a less pleasant word that makes the sudden revelation of the children feel more off kilter and frightening. (I don’t know why for some reason whenever that line comes up I get a sort of twisted version of the children “Want” and “Ignorance” under the Ghost of Christmas Present’s robe in A Christmas Carol, that’s just me, I’m not saying it has anything to do with the song but for some reason that’s what I think of, the sudden shocking revelation of these youngsters). I think the occupants of the barrel, whatever or whoever else they may stand for, are symbols of how he felt betrayed.

“Banana” – I could see that fitting in with the whole theme of insecurity etc, as you mentioned.

ETA: I was just about to hit send when I thought of something, probably has nothing to do with this or when Paul wrote but I guess it’s a possibility, given the “stream of consciousness” way Paul writes sometimes – might make the McLennon’s happy – when John was given that money for his 21st birthday and they went to Paris, didn’t Paul say John let him drink all the banana milkshakes he wanted “He must have been fond of me to have bought me those banana milkshakes” something along those lines? So if he was thinking of anything to do with milkshakes, even metaphorical ones, while his kids may have liked strawberry, Paul’s favorite was apparently banana and it wouldn’t be far from his mind to use his own favorite flavor as a another symbol. The old banana betrayed for the new flavor maybe?

Why do my paragraphs keeping running together? I even put another space in between them this time, hoping it would separate them this time.. Sorry about that, as I know it’s harder to read this way.

@MG, to create spaces between paragraphs, put a period (.) in the spaces between each paragraph you want to separate.

Not so much the banana line but the line about soreness from an enemy’s hose, a piano up his nose and the fact that sucking is the crude way to describe fellatio. If it’s any comfort to Paul fans who hate the happy-go-lucky, superficial stereotype, whatever his subconscious was telling him as he was writing those lyrics, he definitely has a dark side and might be at least as disturbed as John.

I feel he has a dark side and might be at least as disturbed as John.

.

I agree about his having an under-explored dark side and troubles. I think he has traumas from childhood that are barely known. The loss of his mother was terribly compounded by the family’s handling of it; the boys weren’t told she was sick, weren’t told after the fact what she died of, were not allowed at the funeral, and not told where she was buried. They were immediately bundled off to live with relatives because his father was so distraught, possibly suicidal, and impressed upon the need to put on brave faces so as not to further upset Jim. Then there’s Jim’s excessive corporal punishment. I’m also convinced there was something going on with Paul’s teacher(s); recently Paul used the word “abusive” to describe things that went on at his school. He immediately followed up with “Not sexually, tho!” but considering his past comment that some of his teachers were “right perverts”, I consider that a classic Paul “whoops I’ve said too much” walk-back. See also the “Yeah my dad hit me til I was 17–ummmm but it was actually amazing because eventually it made me stand up to him!” story.

.

Is it any wonder he heard about LSD’s power to illuminate one’s deep inner psyche and was like “HARD PASS” for 2 years?

Not so much the banana line but the verses about his being sore from an enemy’s hose, a piano up his nose and the fact that sucking is the crude way to describe fellatio. For Paul fans who hate the thumbs-up, superificial stereotype he gets, whatever his subconscious was telling him as he was writing down these lyrics, I feel he has a dark side and might be at least as disturbed as John.

I can see the hose and the sucking–what’s the significance of a piano up the nose?

.

Besides the life traumas, and even tho it’s John who’s often speculated to have had bipolar disorder, I think there’s a real chance Paul does. He might be one of the rare (lucky?) ones who’s manic more often than depressed. Or he simply copes with the depressions better, perhaps by the sheer power of his Pathological Positivity™.

.

Am I straying too far from the original topic of this post? Apologies if so!

Sorry for the double post, first and second draft. :/

I was boldly outspoken in attempts to repeat my refrain. These comments are currently un-moderated (obviously, in my case – can you say fellatio on here?)

Hi Michelle, we had to turn off moderation because the site is being comprehensively reworked (long, boring story involving a WordPress update that has revealed how out of date our theme has become –that’s what’s was making so many things break. Hope to have the new version up and running next week. Until then, we’re trusting everyone to get along!

.

But even if we WERE moderating comments, we would OK saying “fellatio” as the long as the conversation is about something substantive. Abuse of others and spamming are the things we’re really watching out for.

Annie, very interesting about Paul’s teachers. It always intrigues me when he lets something slip or reveals something about himself and his experiences. It’s so rare that he does it. He bottles it up which I’m not sure is healthier than John’s method. Paul even said in one of my favorite interviews of his in 1986, “I still haven’t [gotten a perspective on the pain during the last days of the Beatles]. It’s still inside me. John was lucky. He got all his hurt out. I’m a different sort of a personality. There’s still a lot inside me that’s trying to work it out.”

Oh my goodness. I think it is fine to try and look beyond the surface, but I also think people should be careful. After all, you are talking about real people here. Now all of a sudden Jim McCartney is an excessive hitter and the teacher’s are paedophiles – come on!

@Jesse: sure they’re real people, but so is Julia and we talk about her effect on John. I don’t think Jim made Paul feel unwanted or worthless, like Julia did John, which is arguably worse. I don’t think Jim was a monster, but yeah, I do think he hit his kids too much (even for that time period). And according to Paul’s brother, Paul absolutely hated it and would always rage and cry afterward.

.

As for the teachers, I mean, I only have Paul’s words: that one of some of them were “perverts” and “abusive.” Make of it what you will I guess, but those are strong words. He probably had dozens of teachers, there’s no way to know who he’s talking about, I’m not accusing anyone. In any case, child sexual abuse should never really come as a surprise; it’s appallingly common. And Paul would have fit a demographic often targeted by abusers.

.

The thing is: in addition to his many good and sensitive and generous qualities, Paul also has a core of absolute steel in him, so much so that an insider (ughhh I can’t remember who…someone like Pete Shotton or Ivan Vaughn I think) said that “Paul was the only one who was never afraid of John.” And he took to handling John like a duck to water, apparently. Where does that sort of nerve and savvy come from? It has to be learned somehow.

Annie, Michael Gerber who is one of the creators of Hey Dull Blog had some interesting opinions re: their family lives, including Paul’s, that relate to possible addictive behaviors in their families as they were growing up and how it shaped them. Very insightful and definitely seem to fit a lot of The Beatles behaviors and interactions with each other and other people as adults. I seem to recall, and I might be remembering this incorrectly so I ask Michael Gerber’s forgiveness If I’m wrong, him mentioning something along the lines of what you said re: Paul and his ability to “handle” John. You may have come across them already but if not they are something to keep a look out for in the comment sections of some of the posts here.

@MG: Yes, I have read some of those comments of Michael Gerber’s, and I think he makes really good points. If Paul has addict genes in his family tree, he is lucky as hell that he didn’t get hooked (longterm) on cocaine, booze, or pills. And ASTOUNDINGLY lucky his body had such a strong NO THANKS reaction to his one heroin experience. Is it possible to be so entrenched in the “caretaker” role, psychologically, that you are less susceptible to addiction, physiologically (paging Michael Gerber)? Maybe that’s one reason Paul resisted LSD so long, when he saw the others trying it. Sort of a “Whoa now, my job is to keep my head on straight when everyone else is getting soused” mentality.

.

There is the cannabis, of course. Tho I have to say, if there was one substance for Paul to wallow in, that was probably the safest one. It’s not like it made him lazy and unproductive — ha!! Who knows, without it he might’ve ruined his health by overwork, or simply been too restless to maintain the family life he wanted. Took a big toll on his voice, tho, sadly.

.

I was also reading some interesting articles about the use of cannabis for PTSD patients. Specifically, how it can actually help block traumatic memories and prevent flashbacks. Maybe it had that effect on him and that’s why he fell in love with it; maybe it helped him cope with childhood traumas, and is the reason he now seems able to look back on Beatlemania with a rosier view than the others. I remember him saying something about it all being “like a bad vacation; you only remember the good parts” which made me go, “Um, Paul, I don’t think bad vacations are like that for most people.” Heh.

I’m in the US and trying to buy a Kindle version of this from the UK Amazon site. I did it before with Lewisohn’s book (changed my address to 10 Mathew Street in Liverpool :0), but it’s not working now. Has anyone else managed to buy a Kindle from another country recently?

.

Great job on the site! I can post from my phone now.

Laura, oh my gosh, that’s how I bought Lewisohn’s book too! Except I changed my address to Forthlin Rd. LOL Unfortunately I haven’t tried to do anything like that recently as there aren’t any books I’m looking to get from the UK. I do hope it will work whenver Lewisohn get’s around to publishing Volume 2.

@Nancy @Jesse re: “biretta” — WHAAAT?? My life is a lieeeee!!!! 😉 Thanks for the info, another interesting twist!

.

The site is letting me post today, hurrah!

Hi, everyone! I am new to your site and as a life-long Beatle fan I am thrilled to see such detailed and in-depth Beatles discussion and hope I may join. As for MMD, ages ago I was told that the “piano up my nose” there stands metaphorically for huge amounts of cocaine. Then, “the piano was boldly outspoken….” would refer to the way the drug appears to be almost actively calling you to take another dose. Never questioned that as I am not a native speaker. But as none of you has mentioned it, I would be very interested to know what you think of it and whether you think it a legitimate take at the meaning of this line. Paul said himself that he did drink heavily and did cocaine up in Scotland at that time, so it might fit the picture …

Similarly, I was explained about Monkberry Moon Delight that he might have used “moon” the way they were apparently using it at the times of the Prohibition when anything to do with the “moon” in the name of a drink was used to indicate drinks containing alcohol, produced and sold then illegally and known as “moonshine”. I was told it by several people on different occasions, but I don’t really know if it makes any sense. Have you ever heard of it? Just curious, as both explanations fit really well into Paul’s realities up in Scotland at the time but it also might be reading too much and too literal into it.

As for “two youngsters concealed in the barrel”, I don’t know why but I have always seen them as young, pre-fame John and Paul at the height of their friendship and all that has happened to them and their friendship since. The sight he wants to escape from but it’s haunting him down anyway, making him stand and gaze “with a knot in his stomach”. Just an impression.

I figured his tangled hair was a reference to his pubes because it comes right after the description of his banana. Who is Billy Budapest?

“Horrible sound of tomato”… my first thought was the original lyric for With a Little Help from My Friends: What would you do if I sang out of tune/Would you throw a tomato at me. Maybe John heard references to Sgt. Pepper as well. What did he mean by the opening line of HDYS: So Sgt. Pepper took you by surprise/You better see right through that mother’s eyes?