- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

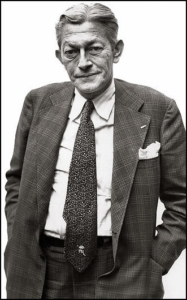

James Angleton, head of CIA Counterintelligence from 1954-1975. His opinion about The Beatles remains a mystery.

Just a quick post, but a thought that I believe is important enough to surface up top.

Recently some commenters have been using the Krays thread to explore conspiracy theories surrounding John Lennon’s murder. This topic is, to me, more than fair game—it has been bubbling under the surface of Hey Dullblog for at least a decade, and I am perfectly happy to have commenters surmise, as long as it’s done in an appropriately forensic manner. Adults speaking facts to other adults. What do I mean by “adult”? Let me illustrate this with a personal story.

As I’ve said, I spent many years happily (?) reading about the assassinations of the 60s. One of the main villains of the JFK murder is a man named James Angleton (for some reason his middle name “Jesus” is often included, but invariably mispronounced—Angleton’s mother was Mexican). Angleton ran the Counterintelligence Desk at CIA for many years, which means not only did he know where all the bodies were buried, he buried more than a few of them himself. Angleton, with his subordinates Anne Goodpasture and Ray Rocca, is the main suspect for “the CIA did it” versions of the plot, which I personally think is the most likely.

So I have spent most of my adult life thinking that Jim Angleton was probably a bad guy, who did a bad thing, for bad reasons. A person whom the world would’ve been better off without. Then I had lunch with my friend Mary.

Mary mentioned that she’d grown up in Washington and Japan, in a family full of generals, and that her father had been head of intelligence for MacArthur in Japan. I mentioned some Kennedy thing, as I would, and Mary immediately said, “Well, I don’t know anything about that, but Jim Angleton was one of my father’s closest friends. He was always so sweet to me as a little girl; of all Dad’s buddies, Jim was the only one who’d ever sit with me and ask questions about my life. Who my friends were, what I liked, how school was going. He was the only person in my father’s will who wasn’t blood. I adored Jim Angleton.”

My point isn’t just that villains can be nice to little girls, but that of course they are. And those little goodnesses do count, or should count, when we’re trying to understand people and figure out what they did here during their few brief turns around the Sun. Insisting that a person must be all good or all bad is probably the single biggest barrier to seeing who they really were. Which, since we’re not St. Peter guarding the Pearly Gates, is all we can or should hope to do.

A new commenter, @Neal Schier, asked whether it was possible to write a biography about a person you didn’t like. I think it would be hard, very very hard. It seems that positive bias can be dialed back closer to neutrality than negative can. Maybe this is because you have to live with your subject; you really do have to re-create the person for the page, and that means they live with you, in your mind, for as long as you’re writing the project. They’re like a roommate. It’s easier by far to live with a good roommate than a bad one; and it’s easier to think that a good roommate did a few bad things, than the reverse.

This is why I generally believe Albert Goldman’s line that he went into the project admiring John (though I think he would’ve still dished the dirt; one of the best things about Goldman is that, because he came from a particular time and place, he rather over-values honesty and rather over-abhors propriety). And I think if he did sign the book contract liking Lennon, but then unearthed lots of information that he found distasteful—that a man he felt was honest, wasn’t—it would explain the profound sourness of The Lives of John Lennon. The fury behind it. I can relate to that fury, maybe you can too. It’s pretty much impossible to be a Beatles fan after a certain age, and not be genuinely cross with Lennon about a lot of the decisions he made, people he hung out with, and so forth. NOT because you want more Beatle tunes–as Lennon was already beginning to argue in 1980–but for the devastating personal price he paid.

We attempt here on Dullblog to be even-handed and, I hope, even compassionate towards these figures, many of whom get lots of worship but very little simple human compassion. Even the few “villains” of the piece–Allen Klein, for example, or Dizz Gillespie–are far from being all villains, and have positive qualities that should be noted because those qualities were a huge part of the story, too.

This morning they plot; in the afternoon they’re nice to a little girl; in between they have lunch. That’s what history is, all of it. Anything less is a fable—told by a child frightened of the dark, wishing not for truth but for sleep.

Goldman’s book is written with the fury of John Lennon rejecting the Maharishi or Arthur Janov because they’re not a replacement for Freddie Lennon, and I think John Lennon could relate to that.

Well said as usual, Michael. The only thing I’d offer as counterpoint is that Angleton may have been an example of someone evil who thought or had persuaded himself he was doing the right thing for America or democracy. Maybe people like Sam or John Green thought something similar about whatever they were doing in the Dakota, I don’t know. But as semi-historical figures, it’s hard not to see them as more one-dimensional , even accounting for the fact that every human being is messy and complex.

Certainly important to keep in mind when having these discussions. For example, we discuss Yoko a lot here, and I’m someone who doesn’t see her influence on John as being particularly salutary, especially in the Dakota years when she seems not to have been very supportive of or concerned for him. On the other hand we must remember that, whatever the nature of your marriage, if your husband kicked you in the stomach while you were pregnant and you miscarried, as it’s been alleged that John did, you might not give a shit either.

Oh, I think there’s no question that if Angleton made a few phone calls, he thought he was doing the right thing for America or democracy.

Unless HE was the mole that he so fervently sought inside CIA. (He was an acolyte of Kim Philby.)

People do all sorts of lousy things in the heat of a moment, then regret it. There’s always that possibility too. When I read late Lennon interviews, I feel a lot of regret coming off them. And I’m sure Yoko had her share of regrets too. Two complicated people in close quarters for a long time, bound together by the images they’d created and felt they had to maintain…Whether they were happy together or sad in 1980 (which depends on who you believe), they were always two tigers in the same small cage. And perhaps the biggest tragedy of December 8 was that it ended any chance of reconciliation–for anyone.

The Krays thread has a lot of talk about various conspiracy theories, but I think regardless of what happened in 1980, John and Yoko were both acutely aware of how stuck they were by the images they’d propounded for 12 years about their relationship. They didn’t have a lot of good options for walking that stuff back, and the good options depended on them being emotionally healthier than they were.

I agree with this. The one thing we know FOR SURE about both John and Yoko is that they despise/despised any sense of public humiliation or embarrassment. A divorce would have been a tremendous black eye for them both, and the spinning/disdain for the public would’ve been immense.

Part of me agrees, but another part remembers the naked photos and seeming compulsion to seek attention, even negative attention. And there was an obvious angle they could have played: Once again being progressive and visionary by being the world’s most civil and mature divorcee co-parents. With some (possibly justified) psychobabble about how humans aren’t designed for monogamy/life-mating. Or some such. Yoko at least could have easily stuck to that script, tho John was more volatile and might’ve slipped, OR gone off script on purpose if he got mad enough and denounced the ballad as a myth just like The Beatles/Paul 10 years earlier. (“I’ve seen thru religion from Jesus to YOKO!” *cue swelling strings of resentment*)

.

But then that might have taken an effort too huge for John to undertake at that time in his life. He seems so ill (psychically and/or physically) in the late ’70s. He may have been literally starving, and the impact that has on a person’s brain cannot be overestimated. (Note on that, btw: eating disorders are notoriously pernicious, and we should be careful of blaming Yoko for not “saving” him. She could have begged him every day to eat, sent him to therapy, done everything right, and John might still have starved to death. Frequent occurrence with eating disorders, which have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder. Just sayin.)

Excellent comment. Thanks!

This is such a brilliant comment, Annie, and I totally agree on both your points around the ‘Yoko should have saved John’ narrative, and the naked photo being a good indication that they didn’t mind public embarrassment as long as it takes the form of press coverage.

It’s really fascinating, especially because Beatle John is so easily humiliated and reacts so strongly to even to the slightest possibility of embarrassment, either with pre-emptive cruelty or, if he couldn’t get away with that, having the last acerbic word in an exchange, but then he flips into this ‘we’ll be the world’s clowns’ version of himself almost overnight. When I hear that “one has to completely humiliate oneself to be a Beatle” quote from John, it always makes me laugh with his later JohnanadYoko antics in mind.

Maybe John and Yoko had a high tolerance for criticism/embarrassment, but only so long as they were in control — by deliberately courting, or at least anticipating, it in advance, having a soundbite prepared in response, etc. But if it came from an unexpected quarter or was aimed at a sensitive spot, they had a very (very) LOW tolerance. Like John’s embarrassing dismissal of that Vietnam war journalist during the bed-in… shoot, I forget her name.

Gloria Emerson, @Annie. More here: https://www.heydullblog.com/john-lennon/gloria-emerson/

John and Yoko were incredibly touchy, as most really famous people are.

Fantastic comment, but I think there’s a difference between negative attention that they could look down as being hippier/holier than thou (“we’re artists, and the stupid public doesn’t get it”), and negative attention resulting from actually feeling humiliated or being held to account for past statements. John certainly didn’t seem to revel in being asked about How Do You Sleep, for example.

@Annie M

Well said!

Catching up on this blog and the comments has changed much of my thinking of just what JL could have done. I realize I am a bit late to the game in having the light go on in this regard, but comments such as yours regarding his diet/health marks the fact that JL’s agency was apparently so reduced that it is anyone’s guess as to what he could have done even if had he wished.

Therein lies a great human tragedy no matter what one’s station in life–that an individual could be wishing to make course corrections but, for many reasons, cannot. That assumes, of course, that the individual even knows what the new course should be or even that changes are necessary for long-term survival.

@Michael Gerber

Thank you for addressing my question in such depth. It must be a real challenge for any writer/historian to keep an even keel when addressing persons in whom he or she has an interest, appreciation, emotional investiture, or other admixtures that might color the examination. That is why I don’t think that explorations of the Beatles are at an end. We remain open to new material (as scarce as it might be I admit) and fresh interpretations that can hew to facts and not emotions.

“Was John’s assassination political?” I see that question sometimes.

Isn’t everything political?

One villain (he’s been described as “unwitting” but I’ll call him a villain) who always gets mentioned in passing is Dana Reeves. I’ve seen him described as an aspiring cop and sometimes as a sheriff’s deputy, depending on which account I read. Either way, he was a law enforcement guy in Atlanta, Georgia.

So what do you do when you’re an aspiring cop or sheriff’s deputy in Atlanta, and your friend tells you he’s visiting NYC? “I bought a gun to take with me but I need bullets.”

Do you say to your friend “Jeez, I don’t think that’s necessary.” ? No. You say “New York City?! Damn, boy, you’re brave! Sure, here’s five bullets. And these aren’t regular bullets, they’re hollow-point!”

I’m not sure how skilled Chapman was at concealing his mental illness:

Maybe Chapman was clever enough to hide his mental deterioration from his friend the Atlanta (wanna be?) cop. Or maybe a man like Reeves, in his time and place, with his racial assumptions, thought it was perfectly reasonable for his nervous friend Mark to insist on being armed before visiting New York.

Has anyone ever asked Reeves “What on earth were you thinking?” Every story I’ve read, he’s described as unwitting. I mean, sure. I believe he didn’t expect Lennon to be the target. He wasn’t part of some assassination plot. But was he thinking “I hope you kill some n****rs with these hollow-points” when he handed over the ammunition?

Journalists who made the assassination their beat never lingered on Reeves’ motivations. I’m sure he was a charming guy when they interviewed him. “Your friend was scared about visiting crime-ridden NYC, so of course you gave him bullets.” Perfectly reasonable, and then the journalist moves on with no followup questions.

I spent a lot of time in NYC in the mid to late 1970s. I did a lot of driving and a lot of walking. My car was broken into once. My best friend had his wallet stolen. Lots of homeless people wanted to clean my windshield for tips. But it never would have occurred to me to buy a gun.

But to a White guy in Atlanta? His friend seems a little off. More nervous than the last time he saw him. His eyes don’t look right. Rambles when he talks, too. But he’s going to New York? Reeves has heard stories about that place! Better take these hollow-points. “They’ll stop those thugs in their tracks!”

The “He’s different, I’m afraid of him” quote is from this:

https://chipcoffeyblog.tumblr.com/post/69389400093/with-a-little-help-from-my-friends-did-demons-force

I agree demons were involved, but not the kind Chip Coffey suggests.

I 100% agree with this, and remember thinking at the time that this was disgusting in the extreme.

And one of the ways that gun-worship in one area of the country, worsens life for the rest of us. If Lennon had lived in London or Tokyo, he might be alive today.

If I may bounce off-topic (fully understanding that this comment may never reach publication for being off-topic, but happy to debate with you privately, Michael)… I buy a government cover-up of the JFK thing, but not a government hit. I think the Mob, and here’s why.

When you think about it, the U.S. government has never actually had a huge problem with the Mafia. It took one crusader who finally had to resort to tax evasion charges to nail Al Capone; no one was looking too hard for the guy, because organized crime is useful if you put the emphasis on “organized.” Solving crime becomes a lot easier when you always know who’s responsible, and if it’s not performed out in the open, we conduct periodic arrests to keep the books straight, and especially if we get a cut of the take, the government generally doesn’t care. Shit, on a number of occasions, the government has used the Mob for its harder jobs. Google “Operation Underworld” and “Operation Husky” for the WWII-era stuff, fast-forward to how we tried to use them to take out Castro, and throw in a side order of Gregory “The Grim Reaper” Scarpa breaking the case of the Vernon Dahmer fire-bombing in a “special assignment” that netted him 30 grand.

(Frankly, organized crime has always kept the peace and even been fairly more progressive than the government, though often for selfish ends. Look at how they ran gay clubs back in the day; say what you will about the poor conditions and underhanded business tactics forced on them by society, but the O.G.s saw a business opportunity and provided the LGBT community with a much-needed haven at a time when the rest of the country was still hostile and unwelcoming. But I digress…)

The Mob put money, muscle, and considerable influence into JFK’s election at the instigation of his father, who they knew from way back as a bootlegger. They were led to believe that things would be same as always or even improve. And, though — tellingly — he never looked into voter fraud, RFK, who’d evidently learned nothing from his old man about welshing on deals, was appointed to head the Justice Department and made fighting organized crime a priority. As Victor Navasky put it in his book, Kennedy Justice, “…ever since Prohibition… attorneys general have been ‘declaring war’ on organized crime, but Robert Kennedy was the first to fight one.”

So they bit back. JFK found out a Dallas welcome is only about twelve seconds long, and it ain’t pretty. As he’d already pissed off other machinery in high places, machinery that wasn’t upset to see him dead for their own reasons but also didn’t want to admit the Mob could take them out so swiftly and decisively with one blow, the nets descended and the cover-up began.

Jim Garrison says in the film JFK, “Could the mob change the parade route, or eliminate the protection for the President? Could the mob send Oswald to Russia and get him back? Get the FBI, the CIA and the Dallas Police to mess up the investigation? Get the Warren Commission appointed to cover it up? Wreck the autopsy? Influence the national media to go to sleep?” No, they couldn’t, not that some of that stuff happened to begin with. But the people who could had two reasons to do so: 1) they were less fond of JFK for their own reasons (the war industry was not happy about de-escalation in Vietnam, for one), and 2) they were definitely afraid of looking weak because they underestimated some “scrappy thugs” who took out the big cheese and revealed just how fragile they really were. And being afraid of looking weak is as American as apple pie.

@g_i_b, this is indeed off-topic, but I’m going to address it, because it illuminates my angle on the Lennon murder.

That is a sensible, well-argued alternative theory. But whether you or Bob Blakey tell the story, the Mafia angle just doesn’t satisfy me personally, and here’s why.

It’s a shooter-based theory, and shooters don’t matter. It doesn’t matter if it was three people from Cicero, four from New Orleans, or five from Corsica; doesn’t matter if they were on the Knoll, the Dal-Tex building, the Depository, the storm drain, or all of these. To me, the specifics of the murder are only important insofar as they can tell you who paid for it, and who paid for it is only important only insofar as it can tell you why. So, perhaps the Mob provided the shooters; I actually think that’s likely. But the Mob wasn’t the originator of the plot. The whole Commission (Mafia, not Warren) would’ve had to decide ahead of time, and there’s no evidence they’d agreed to any such fact. (In fact, the Thomas Dewey incident in ’35 is a great example of how they’d react negatively.) And if Trafficante or Marcello or Giancana did it freelancing, what would the New York families think of that? Carlo Gambino, who didn’t deal drugs because it attracted too much attention? “So, Santos–Carlos–Momo–you have a beef with the guy, and then *I* have to worry about getting hassled? How will you protect me from blowback from what you do?” It’s not enough to kill the President, a tall order; it’s staying alive after.

Sure the Mob grew to hate JFK and perhaps felt betrayed by him and Bobby, but the hate of armed people is not the key in a successful assassination; it’s the lapse in protection, and foreknowledge of same. Why did the motorcade not follow standard Secret Service procedure? (Slow hairpin turn; President at front of motorcade; no agents on running boards; windows were not secured; and so forth.) All this unquestionably happened, all on the same day, and is not within the control of the Mafia. So a Mafia theory rests on a series of unforgivable Secret Service fuckups all being random occurrences, and a Mafia hit squad just happening to be in Dealey Plaza. I can’t believe that. At the very least, someone in the SS had to tip them off, and that has to be within the government. Also? Important to note that nobody on the Secret Service got fired in the wake of Kennedy’s murder. WTAF? What do you think would’ve happened to the Secret Service man who tipped off the Mafia?

There are several things about the cover-up that make it notable. First, it began mere moments after the shooting, with individuals showing Secret Service credentials preventing people from running up the Knoll towards the train yard. Except…there was no Secret Service on the ground in Dealey Plaza. This could be the Mafia, but Technical Services Division of CIA was responsible for those credentials so someone in TSS would’ve had to give the bad guys credentials, or loaned them credentials to forge. Even if they were a couple of mob-types with homemade ID, how did *they* know there wouldn’t be REAL Secret Service around? Or Dallas police? Seems like a great way to get arrested at the scene of an assassination, get interrogated (tortured), and give up the whole plot. Once again: a huge risk for the Mob.

Then, there was massive, immediate, systematic destruction of evidence. It began at Parkland Hospital, where SS personnel were hosing down the motorcade to remove blood-spatter and gathering bullets without clear chains-of-evidence. It apparently intensified at Bethesda, where the wounds described in the autopsy are different from those described by Dr. McClelland in Trauma Room One; who’s mistaken here, Humes or McClelland? If neither is mistaken, who monkeyed with the body? None of these are things the Mafia can control. Finally, the Warren Commission worked hard to codify the lone nut story–no Mafia people were on the WC, but Allen Dulles was.

Oswald had some Mob connections, but he had more intelligence ones. He was an FBI informant at the time of the murder, and may have been receiving money from the CIA (some believe that’s why his tax forms haven’t been released). His ease of defection (with Classified information learned at Atsugi!) and his training at the Monterrey School for Languages, and his easy return to the US, and his Defense-related job at a photo lab in Dallas, and his call to North Carolina while in custody all point towards his being involved in the Planned Defector program of CIA. (That’s Angleton, btw.) The actions of Jack Ruby suggest that the Mafia was involved in Oswald’s murder, but that doesn’t explain why the government accepted Ruby’s claim that he “did it to spare Jackie.” That’s preposterous; no DA would simply accept that and move on.

At this late date, with all this information, the JFK case is a Rorschach test. In my world, based on what I’ve read about both groups, the USG allows organized crime to exist, and some branches of it prosecute mobsters (the DOJ) while others use them at their convenience (the intelligence people). From the Mafia angle: no sane mobster would kill the President on his own; and the Mafia wouldn’t take on that risk, just because a few members were angry at the President. From the USG angle: “Being afraid of looking weak” is a really thin reason for a coverup; it’s easier to pin the murder on the Mafia, then slaughter/deport a bunch of traitorous, “un-American” (read: non-WASP) mobsters who killed the President, to the acclaim of a grateful nation.

This may be my own inner mobster coming out, but I would argue that a Mafia plot external to the USG would’ve been seen as a perfect opportunity to wipe them all out, and take their rackets. There’s nothing that the Mob had on the USG–including the supposed pictures of Hoover fellating Clyde Tolson–that the USG couldn’t easily suppress or explain away. Where would those pictures have been published in 1963? And how many milliseconds would that newspaper stay in business after that? What could Sam Giancana say to anyone, public or private, that the average American would’ve believed over the word of the President? The Mob had zero real leverage over the USG; why would the USG not crucify them, and make the remnants a wholly-owned subsidiary of CIA?

IMHO–and I’m speaking as a guy whose great-grandfather used to watch “The Untouchables” and root for the wrong side–taking a shot at John Kennedy would’ve been absolute suicide for the Mob…unless someone at the top of intelligence asked them to do it, paid them for their trouble, and protected them after.

Do you think the same risk reward calculus is true for Lennon in 1980? Or do you think that it’s sufficiently possible (not easy but possible) for private citizens, albeit with intelligence backgrounds, to speak to the right people in New York law enforcement, find a guy who knew a guy, etc.?

Sorry, I don’t understand the question.

Let me ask you a counter question: think Trump ever had anyone whacked?

Oh I think I know what you’re asking.

No, I don’t think anybody in the halls of power would’ve been committed to protecting (or avenging) a rock star. In the intelligence community particularly, many there would’ve seen Lennon as an enemy. More an enemy, in fact, than most mobsters who are politically conservative. With Lennon, there would be no institutional reaction to worry about.

CIA and affiliated agencies in 1963 was full of people who—regardless of who they voted for—considered themselves Patriots, and were in all-out war versus the Soviets. The operations people had fought in World War II, and took things like American prestige and power very seriously. The idea that they would knowingly allow a bunch of gangsters shoot the President is impossible. At the very least, there would be irregular spooky action “to right the wrong.” Which there was not. Giancana was murdered before he testified in 1975, not in December 1963.

Think about it: if a gangster has something on you, that’s a reason to kill him, not hold back. The reason to hold back is if your boss (say Angleton) has a file on you. Blackmail can be outmaneuvered; blackmail plus government power? You’re toast.

To bullet-point a few things…

The whole Commission (Mafia, not Warren) would’ve had to decide ahead of time, and there’s no evidence they’d agreed to any such fact.

But there is evidence that several parties on that commission were in agreement it had to happen (Hoffa, Trafficante, and Marcello, to name three, with Giancana possibly supplying the guns depending on whose account you believe), and that the mob has been riddled for decades with infighting over someone making unilateral decisions that affected more than just them. (This is how gang wars occur, and the Dewey incident, as well as Hoffa’s disappearance, is testimony to that.)

Why did the motorcade not follow standard Secret Service procedure? (Slow hairpin turn; President at front of motorcade; no agents on running boards; windows were not secured; and so forth.)

With regard to specific security regarding the hairpin turn, position in the motorcade, and active agents in close proximity, though some of these things were a matter of general practice, in truth a lot of this was actually *not* official standard until after he was killed, and became so as a direct result. Even were that not the case, Kennedy in particular flouted this stuff regularly; just over a week before he was killed, he did a New York motorcade (this should be especially interesting, considering our chatter about how dangerous the Big Apple was perceived to be) with no motorcycle escort and fewer guards than recommended by the police and Secret Service — just two cop cars in front of the limo, one Secret Service car immediately behind. He even instructed they stop for traffic lights. (It was noted, incidentally, that because of this, during the ride into Manhattan, press cars came perilously near side-swiping the limo and an amateur photographer got way too close for comfort taking pictures at a red light before he was chased away.) Funnily enough, it’s been suggested he adopted this attitude because of people bitching about how normal living was interrupted by all the preparations for his visit, and his being too responsive to this criticism may have partially been his downfall in Dallas.

As for securing windows, Eisenhower’s former Press Secretary commented on that the day of (he went to work for a division of ABC, and was naturally tapped during their coverage to offer anecdotal input), saying a rifle from a window of a building was pretty hard to guard against, that it was “impossible” “in a large city,” and in fact that in his years serving Eisenhower, the only time he’d ever seen every window guarded in the line of march was in Tehran when Ike sat down with the Shah of Iran. Whether that’s especially realistic in your view or not, or whether you suspect the guy’s intent in saying that because of his former position, this stuff was widely considered normal in that halcyon era when people didn’t lock their doors at night and the neighborhood used to be so calm.

All of the above is easily verifiable, and was widely reported in the days pre-Warren when people were looking for someone to blame and Oswald had only just been arrested; the NY stuff in particular was in the Daily News the very next day. (And, for the mob to act on the info, all it would’ve taken would be literally to watch and take notes, especially in NY. Who needs a tip-off when they can go see for themselves?)

Whatever we’re doing now was not always in place then, and it would be a mistake to look back with modern eyes and say anything but “Lesson learned.”

Important to note that nobody on the Secret Service got fired in the wake of Kennedy’s murder. WTAF?

Actually, someone was, but not directly about it and more for the fact that they were making noise about the Secret Service having foiled a previous attempt in Chicago and thinking their job was done. Look into Abraham Bolden some time. (He also includes the intriguing note that he heard agents displeased with the President’s integration policies state that they would not attempt to protect him if someone tried to kill him. Apparently it’s not just good men doing nothing that helps evil prevail; there’s also idiots who disagree with you not doing their job for their own stupid reasons.)

Then, there was massive, immediate, systematic destruction of evidence.

And remind me how much of that involved scrubbing every mob tie from the picture again? David Scheim’s got a whole book on the subject. (Incidentally, Pat Speer makes a compelling argument that, while there was some chicanery, the medical evidence was not nearly as messed with as people claim. Well worth the read; he goes in deep.)

To answer a more general point you’re making: as you concede, and as I point out, the government — or elements thereof — regularly tapped the Mafia as a resource going back to WWII. On the Castro effort alone, people like John Roselli were being given access to CIA training bases and addressed as “Colonel.” If you think they weren’t mentally comparing notes about how the railroad was run and picking up tricks, especially if three of the major figures were gonna go off halfcocked and take out the big cheese, you’re underestimating their critical thinking skills. Does it seem like coincidence that they pick Oswald (who used to run numbers for his uncle, the bookie), with all his government ties, to be the patsy and ensure that at the very least there will be a lot of eyebrows raised?

There is ample evidence for government involvement here, but I think you’re also underestimating the mob.

Sorry, g_i_b, I wrote a long comment discussing your rebuttal, but I found it made me feel sick, so I deleted it. I can’t talk about this any more. Thanks for the discussion!

I was somewhat aware of Angleton, but I didn’t know many details of his life.

He was a poet at Yale. Edited the college literary magazine. The poets he gravitated toward and corresponded with were folks like E.E. Cummings, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot.

Cummings was a supporter of Joseph McCarthy. Pound was a fascist. And here’s an Eliot quote: “What is still more important [than cultural homogeneity] is unity of religious background, and reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable.”

Somehow I think he wasn’t a big Beatles fan. His daughters probably played Beatle records loudly in his house. I have a mental image of Angleton locking himself in his study at times like that.

@Michael

I am just finishing up with Cloak and Gown and I thank you for having recommended it.

There was an interesting remark by the author that was almost made in passing. He describes the various study groups that were stood up during and after WW2. In the late 40s one of these Yale groups was formed “to determine how the post war world could be formed to serve American interests. ”

Sadly he did not return to this point… one I find encapsulating a curious admixture of overestimation, hubris, and naivete. That we could actually have that much influence, and I admit we perhaps had more influence fuel in our tank than at almost any other time since, seemed to have been rooted in the belief that our military power somehow conjuncted a capability to have an equal cultural, diplomatic, and economic persuasion.

I understand that the concept of noblesse oblige was still extant during that era, but how long did this assumption that the right people could “make it all happen” continue? In other words, were there still those within Yale at the time of the end of, say, the war in Vietnam who advocated for such a broad remit?

Perhaps it was not ever that prevalent at Yale and thus my disappointment that the author did not expand on it, but I wince when I think that it was Bush le fils, who seemed embued with the idea that the U.S. could bring sweeping change to the world.

@Neal, I think the idea that the US could/should “make it all happen” was very common throughout the American ruling class from 1941 to at least 1963; Yale, because it had an outsized tradition of “public service”–remember, it began as a school for ministers–was front-and-center in this belief, but this credo wasn’t in any way Yale-specific. And it wasn’t simply hubris either; thanks to the multiplicative nature of technology, American hegemony in 1945 was probably greater than any single state since…maybe Rome? Remember, too, how much of America’s postwar power was soft power–art and dollars, not armies; which is of course where the Beatles come in. Four boys thousands of miles from America were scarfing down cornflakes and Coke and watching Marlon Brando and listening to American R&B. And eventually creating something in a quintessentially American idiom (rock and roll) that was better and more powerful than the original. Was Beatle music part of American power? No, it was English culture; but yes, in that it was considered by the Soviets to be deeply subversive in the same way American culture was. Certainly at some point I think you have to begin talking about “the West” rather than America, simply to acknowledge the polyglot nature of such things.

Before you judge the “remake the world” attitude too harshly, remember that it’s no different than the many generations who believed that it was right and proper to hasten worldwide Communism. It’s the same attitude, just a different system. The Manichean nature of the Cold War hardened that attitude on both sides; it was in some ways offensive–“we want to remake the world”–but also defensive–“we are terrified of being conquered.”

I think there are STILL people, within Yale and outside it, who still believe that the world should most properly be arranged to suit America. I do not think this is wise. I think we have used our power to project our flaws, as well as our virtues. I think empire is a flawed system.

Talking of topsy turvy tales of the unexpected about spies, criticize John le Carré or compliment Kim Philby in comments on articles in the web and you’ll usually get swamped with criticism. So let’s not forget that David Cornwell’s Dad was an associate of the Kray Brothers and did time for insurance fraud. In the same breath don’t forget that Kim Philby was a cousin of Field Marshal Montgomery who was best man at Kim’s father’s wedding.

The foregoing facts are not so much hidden but rather don’t get the exposure they arguably merit because the events relating thereto must have helped shape the lives of both these well-known MI6 officers. What is also of note is that these officers knew each other and of course Philby wrecked Cornwell’s MI6 career.

Some interesting anecdotes about these two are of note in an intriguing news article in TheBurlingtonFiles website dated 31 October 2022 about Pemberton’s People (in MI6), ungentlemanly officers and SAS rogue heroes.