- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

I was responding to a comment regarding the podcast Another Kind of Mind, and the application of “emotional intelligence” to The Beatles, and as I wrote the water grew deep enough for me to want this to be its own post.

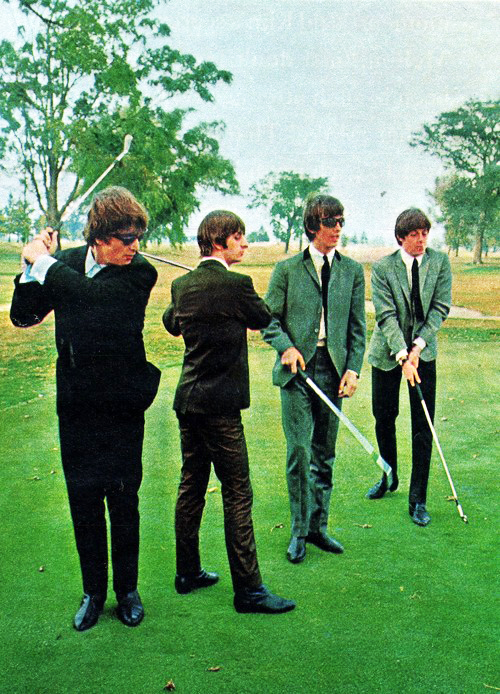

I have long thought—since 1995 or so, when the Anthology finally belched out all the last tracks worth hearing—that the great undiscovered country of Beatle fandom was trying to figure out what the experience was like for John, Paul, George, and Ringo. What, day by day, LP by LP, million by million, did it do to them as people? And we have had over a decade of great fun here at HD doing so; I’m glad this kind of approach seems to be catching on. The idea that these four Englishmen were actually people, not songwriting, peace-advocating, macrobiotics-shilling automatons, or bland mannequins, every shadow bleached out by the glare of the spotlight, is as exciting to me now as it was twenty five years ago.

But the strength of this kind of empathy-based analysis also contains a very great weakness, which is a bit difficult to see at first. Applying one’s own life experience to that of a Beatle–which I do constantly, obviously–assumes that one’s life is similar in some fundamental ways. That there is a shared ground of humanness, or of culture at least, between we fans and them Beatles. But what if there isn’t?

Right off the bat, most of the people applying this emotional analysis are products of this time and place, not that time and place. I was born in 1969 in the U.S.; London in 1967, much less Liverpool in 1957, only exists in my imagination. Like the fellas under discussion, I’m a cisgendered heterosexual white English-speaking man living in the West; but I’m a different class, a different nationality, a different educational background, I have a disability, and I’m a generation younger. Sometimes I might be able to intuit correctly; but in lots of cases, The Beatles might as well be from Mars. So all my conclusions, even the vehement ones, are conditional and held with an internal suspicion that I am full of of it.

So that’s me. But what about fans in general?

First, ironically, is the barrier of fame. The Beatles were massively, impossibly famous from an early age; this changes a person, because it changes the world a person lives in. People, even relatives, treated them differently. They could go a lot of places you and I could not, but also couldn’t go a lot of places we can. I don’t think it’s bullshit when Paul said he missed “riding the bus.”

In addition to inhabiting a gilded cage, J/P/G/R were monitored constantly via photographs and interviews — and a certain type of fan (wrongly) looked to them for guidance. This gave their every public action and utterance a weight that yours and mine do not have. When they took LSD, it was international news; when one showed his willy in public, it was a scandal. So in addition to all the normal no-fly zones that a cisgendered, heterosexual Englishman might possess in 1969, for the Fabs, it was worse. For them, then, there was an immense sense of consequence to purely personal decisions that mere mortals don’t have to contend with.

Then there is the fact of wealth, which changed how they spent their time. The Beatles were massively wealthy, which means that the main activity of most people’s lives — working for others to stay alive — was not something they did. In some ways, they were free. But they were also freighted by something that we can’t relate to: everyone who met them thought that they could change their lives with a smile, so nobody ever told them “no.” They were surrounded by people who wanted something from them, and would do almost anything to get it (including, perhaps, kill them — it happened to Hendrix). Being in that position — whether you’re Nero or John Lennon — messes with your mind. At the very least, it engenders a really huge paranoia and alienation, and feeds a kind of megalomania that you and I just can’t relate to. To put it another way: yes, it was the drugs that made John Lennon declare that he was Jesus, but after Beatlemania, you can’t blame him for jumping to that conclusion. It was only slightly more unlikely than what actually happened.

Then there is the question of talent. I’m a pretty talented guy; I’m sure many of you are pretty talented, too. We have, as they say, our moments. But the Beatles were freakin’ geniuses, upon whose genius was built a whole new profession and industry. Closer to home, John and Paul needed to keep being geniuses for the game to continue and everyone’s bills to get paid. The pressure on them was unfathomable, immense, and it’s only because it happened so young that they didn’t freeze up instantly.

It is incredible that John, Paul, George and Ringo kept the game going as long as they did. After 1964, nobody assumed that they would stay popular, much less continue to innovate while making more and more money. Like I said, I’m a talented guy, who has worked his ass off writing since age 12 or so. I’ve had some success. I’ve even had fans, and endured the sensation of not living up to their expectations, something I suspect J/P/G/R felt a lot. But even with all this, I cannot imagine what it was like to be a Beatle, in an artistic sense; the Beatles were unique even among the universe of their peers.

The Beatles got everything they wanted at a very early age, then looked around and thought, “Is that all there is?” Most of us walk around in pursuit of sense gratification — looking for sex, or food, or comfort. The Beatles had that permanently secured by 1965, 1966 at the latest. Which is when they began investigating psychological/spiritual gratification, sometimes through religion, sometimes through drugs. There is a desperation here, a kind of boredom, that normal people do not have to contend with.

I could go on, but you get the picture. Beatle desires were not necessary normal desires; Beatle morality was not necessarily normal morality; Beatle fascinations were not necessarily normal fascinations — because their lives were not normal lives. Their experience was so singular in so many fundamental ways. What were they like as people? What were they like behind closed doors? With all the photos and recordings we feel we must know them…but particularly as I age, I feel it’s impossible to know them. The emotional interplay between the four men was mediated by many powerful factors, some of which were quite unique, and to use one’s own human-sized beliefs and opinions to predict their mental/emotional state is…guessing.

So, out of respect to the guys, I try to show my work. “As someone who has meditated, I can say that…” or “This behavior seems like codependency, as defined like this, and here’s why maybe that was happening…” This allows the reader to check me. Fans love to feel they know these Fabs — myself included — and make declarations about them. That’s more acceptable to me when we’re talking about John and George; it’s less so when we’re talking about Beatles who are still alive.

When we speak about them, we are speaking about ourself. So if you want to understand The Beatles, I suppose the only hope is to understand yourself. And even then, I suspect they will always remain blurry, cloaked in a shimmering, confining nimbus of myth and legend. Mere mortals cannot understand John, Paul, George and Ringo any more than an ancient Roman cobbler could understand Caligula. And if he could for a moment, would he wish for ignorance again? Screened off from the rest of us by sex and fame and money and power and drugs and ennui, we perceive The Beatles through a glass, darkly. That is our pleasure and our pain, and perhaps theirs as well.

Even if the Beatles never made it past their first single, I’d say we’re not equipped to understand them for the simple reason that three years of playing rock music in a German red-light district for eight hours a night while drinking and taking speed to excess likely leads to a lot of changes in your experience of the world and development as a young man that we cannot imagine.

And that leads me to one of the points I like to hammer a lot on this blog: drugs were not neutral nonfactors in this story. Being on speed changes your brain chemistry; being on speed for most of 5 or 6 years in order to do your job probably changes a lot of different things in your brain; being on speed for that amount of time when your job kind of involves being a demigod with all the money and sex and adoration you could ever imagine probably changes it A GREAT DEAL. Getting high often changes your brain chemistry. Doing LSD whenever you have a day off surely changes your brain chemistry. Doing coke changes your brain chemistry.

It should be no surprise that each of the Beatles lived a very weird life after about 1966.

This excellent post doesn’t seem to have gotten the attention it deserved, so I’m going to add to it as I had a thought the other day. One of the many things we incorrectly take for granted about the post-1966 Beatles is that they basically believed the same types of things we believed. Whether it’s George’s devotion to Krishna or John’s apparent beliefs in astrology, magic, numerology, etc., that’s not necessarily the case. As we examine their increasingly weird post-Beatle lives, in particular, that’s an important distinction to remember.

Yes, something I rarely see discussed is John’s apparent belief that he could communicate with the other Beatles (and Yoko) without talking out loud! I don’t know the full extent of this belief, and how long he held it for, but the Get Back sessions certainly look different if you keep that in mind!

I both agree and disagree. I mean, I understand the whimsy in calling us “mere mortals” beside them, but … they are mere mortals, also, flesh and blood and made with the same basic genetic material, with the same basic set of human emotions and basic life experiences as the rest of us. They were born, they ate, they went to school, etc. And sure, they lived through some EXTRAordinary circumstances and a nice cocktail of substances that likely changed them forever, but a lot of people do? I mean, some people are astronauts and go to the moon or space-walk and they’re still human and have human emotions and even go back to functioning in human society. People who lived through the foxholes of WWI were changed forever, but were still human inside and normal people lived with them and understood them to a point. I guess the Beatles had/have everyday realities that are out of our realm of understanding or imagination (i.e., bodyguards, rituals in place to minimize whatever, etc), but, I dunno. I understand the point of keeping an eye on “yourself” and making sure that your emotional reality doesn’t become projected onto someone who is not you, but basically they still have anger, fear, love, fury, sadness, etc.

I think the best-case scenario, yes, is viewing the Beatles emotionally, coupled with the concrete-evidence-based approach. We might have a better understanding if the questions those evidence-seeking researchers asked were different questions with a more comprehensive view of the totality of their existence (i.e., material, emotional, physical, etc) then we might see some differences in their story emerge. Over the years growth in emotional maturity has allowed the Beatles to remember things differently and changed the story as it used to be (i.e., we discovered that Paul’s jealousy of Stu was not tied to his bass but to a rivalry of friendships).

Great comment, thank you.

.

Interestingly, soldiers in WWI were endlessly frustrated by the impossibly of explaining their experiences to people who had not been there. To them, often, only other soldiers could understand.

.

Similarly, the PTSD that they displayed could render even their most basic biological behaviors incomprehensible to civilians. Their very nervous systems had been changed by what had happened to them. That’s what shellshock means.

.

And didn’t George mention that the Beatles had given their very nervous systems to be Beatles? We look at what they went through and think, “Wow.” But imagine for a second what it must’ve felt like to stand in front of 50,000 people who are clearly out of their minds; sure there is exhilaration, but also primal fear. Concert by concert, groupie by groupie, their nervous systems were adapting to deal with overwhelming, unpredictable experience. Your analogy to astronauts is a great one — but it’s as if, once Neil Armstrong went up, he never came back down, he had to live in space.

.

How can you or I possibly know how it feels to see yourself on a movie screen or on television, not once but endlessly for 50 years? The mirror-image — “people think that person up there is me, but I know I’m me, and I’m different than him.” How strange would it be to have millions of people thinking about you all the time, expressing opinions about your motivations and internal emotional states, as if they knew you deeply? Wanting to possess or impress or destroy you? This environment is fundamentally inhuman, because it’s too big. It’s a kind of fame created not by humans interacting IRL, but by image- and sound-technology — just as, beginning with WWI, war changed from a human-scale (and thus relatable) experience, to something made huge by technology, and utterly inexpressible. You had to live it to understand.

.

I think the Beatles was a war fought by four soldiers; and only those four people know what it was like. The rest of us are merely guessing, and when we guess we are revealing — can only reveal —- ourselves and own own experiences, not them and theirs.

.

Finally, a separate point: there is an assumption that earlier writers like Davies or Norman or Spitz or Lewisohn are not applying their emotional intelligence to the Beatles story. I think they are; that is inherent to the writing process. And these writers often share an era, a gender, and sometime a nationality, with their subjects.

.

Journalism, history — these at heart are just as informed as podcasts by the emotional experiences of the writer. It’s impossible for it to be otherwise. Knowing this, you could argue that these earlier scholars are applying a more accurate emotional map to the topic than you or I can, no matter how sympathetic our imagination.

.

So why is there a feeling that the Beatles’ emotional lives haven’t been given sufficient space in the story? For two reasons, I’d argue. The first is that there is less and less factual information to unearth, so restless minds turn inward. The second is, I guess, related to larger cultural movements relating to gender and race and sexuality.

I’m sure it has to do with changing cultural movements, that make things look different when a new light is shone upon them. Maybe those things aren’t true but maybe they are, and I think it’s worth looking at, anyway.

And yes, all those contemporary white dudes brought their own emotional experiences to their books, and we sure did get a range! I mean, Norman (self-admittedly) came from a space where he was apparently jealous of Paul McCartney’s good looks, talent, and success, and somehow tried to make all three of those things worthless. A new look with new brains might provide a broader spectrum of insight, even if it can’t penetrate 100%. Can’t be any worse than Goldman!

And Lewisohn seems stymied by some of the characters’ emotional reactions and I don’t think he’s as strong there as he is in digging up and tying together historical things, and I think he realizes that as a limitation. But honestly, after listening to so many of his podcasts recently I’m really over his own personal emotional agenda, which is VERY visible, so I won’t go into it, haha. (That’s why I don’t have that quote yet for you as discussed on your AKOM post — I’ve listened to too many hours of that man speaking and repeating it was just making me upset. I’ve actually become a little ticked that I spent the money on the extended edition of Tune In, so I need to step away and read someone else.)

@Kristy, I love your comments, keep ‘em comin’!

.

Here’s my point: if you’re going to take Norman and Goldman and Lewisohn—-all very different writers with very different techniques and biases—-and dismiss them as “contemporary white guys”, you’ve also got to keep in mind that our very Beatles were also white guys of that same era. If one’s race, class, orientation, gender, age and nationality are fundamental to how one looks at this stuff, then those very biases are likely to give the commenters insights; and contemporary writers will be misled in important ways.

.

Which is not to say that I’m not all for “new brains” addressing this topic. I am. I think it’s great and shows the fandom will not die out, which is amazing. What I struggle with is these new brains’ opinions claiming a kind of equivalence with the earlier narratives simply because they are new, or because they come from underrepresented demographics.

.

A podcast represents roughly one one-millionth of the scholarly effort of a book. The good ones are basically glosses of a bunch of different books. Podcasts are basically conversations; that’s why we love them and that’s why they’re great. They are valuable and worthy as what they are…but they’re not a book. They are, inherently, more biased than a conventionally published book on the same topic, for a bunch of structural reasons that I can explain if you like.

.

I think Philip Norman tends to undervalue Paul, and I agree that he tends to consider him lightweight because of how he was presented first in the sixties within the group (“the cute Beatle”), and then later thanks to Lennon and Rolling Stone and so forth.

.

But Philip Norman has also *met* Paul many times, and shared many mutual friends—-he couldn’t not have, as a newspaperman in London during the 60s and 70s—-and so we should also keep in mind that perhaps some of Norman’s bias comes from first-hand knowledge, and also reflecting how Paul was perceived at the time, by his peers. Which makes Norman’s bias not just garbage to be thrown out, but also data for us, a tool to understand it all better.

.

Why am I taking the time to thumb all this out on my phone? Here’s why: as you know surely all too well, women under patriarchy are endlessly dismissed because of their attractiveness. So a writer who does that to Paul is 1) going to draw the ire of female fans, and 2) encourage a kind of indentity-swapping by them.

.

In all this latest wave of Beatles thought, I endlessly hear female fans defending Paul, and speaking for Paul, and assuming insight into Paul—-without bracketing any of it with self-knowledge of this identity-swapping. If one concludes x happened to Paul because y happened to yourself, that’s a completely legitimate and quite interesting thing to say—-if the speaker gives us that info. We have to weigh it, judge it. Books like Norman and Goldman and Lewisohn are produced to be judged; and to be honest, anybody who downgrades Goldman also has to acknowledge that the guy and his researchers did a HUGE number of interviews, which not only produced his book, but Spitz’s (at least), and if we’re lucky, will form the backbone, with Lewisohn’s research, of books two hundred years from now.

.

Podcasts, like this blog, are fan talk, not history and not even journalism. They provide enjoyment about a topic we all love and, perhaps, a spur to future angles for formal study. People like Devin write Beatle books; people like Erin do formal Beatle history. That’s an entirely kettle of fish than Dullblog or these podcasts. The internet makes its content feel equivalent to formal history and journalism, but it isn’t. And while Internet content has some real benefits —- “new brains” chief among them —- accepting its assertions of equivalence is a bad thing. It’s what is driving the omnipresence of conspiracy theory and, sadly, the post-rational political movements of our era.

I see your point about equivalency — and just to be clear, I wasn’t saying that Goldman or Norman or Lewisohn are without value, I was just pointing out their self-admitted or at least obvious biases. I mean, I’ve read these books, too, because I wanted information! The note about white dudes was not dismissive, but to show that I understand your point earlier about their contemporariness to the Beatles. But I also understand that just the very phrase “white dudes” is going to evoke a different tone than I was going for. Really, I should know better. 😉

(I actually think Goldman’s book is super-valuable, if only because it contains SO MUCH information and because it presents a point of view that is so very different from what else is out there. I mean, it’s biased as heck, but I have heard about the research involved.)

@Kristy, one of the challenges I have is that I read so many comments on so many posts, I often acknowledge the specific post up top, and then talk more generally. And I think that the commenters are often popping off in this same general way, e.g. “white dudes.” Didn’t bother me a bit, and I wasn’t speaking about your personal thoughtfulness (which is clearly high), but a more general rumination on how easy it is for any of us who have been charmed by these men to identify TOO much with them.

Want to add that Norman has had the courage to own up to his (former) bias in his McCartney biography: he’s lived long enough, and has enough insight, to recognize some of the projection and animosity that motivated the anti-McCartney slant of Shout! and the Lennon bio.

.

To which I say, respect. Much as I offer Mitt Romney respect today despite disagreeing with him on some issues.

Annnnd just to add a postscript – Also, I appreciate your point about Norman’s being there and his bias being a product of his environment, which makes me wonder what was in the originating environment. I mean, with someone like Paul, it all seems to depend on whether you knew him on a good day or a bad day, or in a social or promotional setting versus a studio setting. Or business or personal. Hmm.

You’re right that podcasts are not the true journalism, and in my case, at least, I’ve definitely sought out other sources from what I hear in them.

Just ruminating further, Goldman’s Lennon book is the only Beatles book I’ve read all the way through twice (so far), even though it was so bleak that my soul died a little bit each time I read it. But that wouldn’t have worked unless I could buy the author’s conviction based on the research, and also be sucked in by his writing, which is exceptional. BUT I take it with a grain of salt because of its anger at its subject, and also its racism and sheer dismissal of everyone else in the story. Same with the biases of Norman et al. Not necessarily dismissiveness, but maybe wishing for a little less bias (or, taking into account what I bring with me, a little more bias in a different direction!). Admittedly, I haven’t read Spitz.

(Aside, I think there’s a certain smartassiness in my tone that is part of how I write, and I need to be mindful of that and be more measured here? But please believe that I enter these discussions in all earnestness. My background is in journalism, but either in (a) editing magazines or (b) writing columns where smartassiness was a feature, not a bug.

I think that’s why I resonate with AKOM where other people are turned off; AKOM has a smidge of “je ne sais f**k you” that I enjoy. The guys at Fabcast project more an air of hyperbolic fannish squee, which is fun in a completely different way.)

OK, so as a fellow scrivener you get what I’m saying; I definitely get what you’re saying.

.

(Just as an aside, I’d love to hear more about your background, and what you’re doing now. Email me. The house voice of the internet is, to my ear, 50% old SPY magazine and 50% Robert Benchley. Great as far as it goes, but offhanded snottiness has its limitations as a mode of discourse. One of the reasons this site took hold was that we didn’t sound like the rest of the internet, FWIW.)

.

Goldman’s book is bleak because fame is bleak. It is a bait and switch. And the business around it is particularly destructive, even if those attracted to it weren’t sensitive souls uniquely UNqualified for capitalist maceration. But I’m glad to hear you recognize Goldman’s writing as exceptional. I’d go further; in the Lenny Bruce book, I think it is top-quality New Journalism — and were he alive today, he’d fit right in on the internet.

.

Goldman is a nasty character, no doubt, but he’s also useful in a sort of forensic way; and I read right past all the racism and sexism and such, to the data. Goldman’s descriptions of Yoko’s looks are less than meaningless; his descriptions of her behavior are, to be frank, some of the only information we have on the woman, not provided by her or a lackey. Same goes for most of the people in that book. Do I believe Goldman? No. Do I see him as an essential corrective? Yes. And nobody ever sued him over the book, which is telling.

.

Spitz will probably strike you as weak tea. A bridging work; the story being filled out, like Hertsgaard, only with more workmanlike prose. I wasn’t sad to have read it, though. Norman’s Shout! was good enough for 12-year-old me; his Lennon, I couldn’t finish, and his McCartney, I don’t have any interest in; that felt like an editor’s bright idea — “we’ll have a matched set!”

You can’t sue someone for defaming a dead person.

Of course not, but you can sue someone for defaming YOU, and Yoko was certainly in a position to do that in 1987, with both unlimited resources and unlimited public support.

.

The reaction to Goldman’s book was utterly savage throughout the press, as well.

With Paul and George Martin leading the way in their criticism. Now Goldman’s book has become revered as the tide has tragically turned against John. He also wrote a scathing book about Elvis. He seemed to resent pop stars. I shudder to think what book might be written about Paul when he’s gone. I loved the story of John telling his son Julian, “If you ever become famous, try to outlive your biographers.”

I wouldn’t call Goldman’s book in any way “revered”; I would actually say “reviled” is closer to how the vast majority of Beatles fans look at it. I don’t know a single Beatles person, myself included, who thinks that it is a anything more than a extremely flawed book, with sone elements of usefulness. And that’s the nicest view of it!

.

I don’t think it’s useful as regards Paul or George Martin, for example. I would only use Goldman to learn about John, Yoko, and the drug demimonde, which are really the only things it is interested in. It’s totally misguided about the music, and the other Beatles, for example.

.

The outrage was in fact led by Yoko and Jann Wenner who, IIRC, ran a lengthy article in RS refuting the “errors.” It would be interesting to see how many errors are now accepted, if any.

.

For better or worse, the revisionist idea of John Lennon, peacenik and wife beater, bicurious Beatle, has come mostly from Yoko. Which is the only place it could come from.

.

I don’t think you have to worry about some biographer doing a hatchet job on Paul McCartney. He has diminished that possibility for the happiest reasons; by the time he dies he will not have the type of international hugeness that would support a muckraking book. Whether there is in fact any muck to rake is anyone’s guess; but I don’t feel so great a need to know about it in Paul’s case.

Oh, I agree that Goldman isn’t revered all of a sudden. However, I do respect it and what he did provide that might be truthful, or at least provide a real counterbalance to everything else that’s out there.

I came around too late but would be curious to see some discussion of what people think is true or not-true in Goldman, or even some discussions of the information he collected by other authors who’ve utilized the research. Does anyone know where those discussions might be?

I was reminded again of authorial biases when trying to read a couple of Paul bios I had on hand– Carlin’s and Sandford’s. Sandford’s feelings really have affected the story for me. He seems to have no real affection for Paul McCartney at all– perhaps admiration at his accomplishments and his music, and that’s all I can detect. I particularly see how his bias might have informed one of this book’s theses: near the beginning of the book, Sandford quotes John’s 1970 “Me and Paul were never close,” and he just runs with it. At nearly every thing Paul does, John is angry or sneering. Paul dresses a certain way, and John is annoyed because Paul is showing off. Paul says something, anything, and John is pissed off. Paul does some other random thing, and John is just livid. John comes off almost even worse than Paul in the book because of his constant anger and anti-Semitic invectives against Linda and the rest of the Eastman clan.

So maybe all those things were true, but he didn’t offer the much at all of the “caring, charismatic” John that made people able to stand his bad moods in the first place. So I guess I just suspect Sandford’s personal slant informed the text and ended up making everybody miserable. (Kind of like Goldman did, honestly.)

Carlin’s wasn’t perfect because it had a lot of editorialization and didn’t source so many of the scenes and thoughts he describes. But you can tell the author doesn’t hate his subject! It’s a lot more even, a little softer at Paul, though not forgiving of every little thing he’s done (see what I did there), and even reporting the story behind the royalties lawsuit that ML likes to bring up repeatedly in case it’s forgotten. And Carlin at least does seem to get the connection between John and Paul and the importance of their partnership. He doesn’t shy away from their disagreements but explores them in a more evenhanded way.

Thanks for the info on Spitz. I have heard he used Goldman’s research, so I might check it out just for the heck of it.