- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

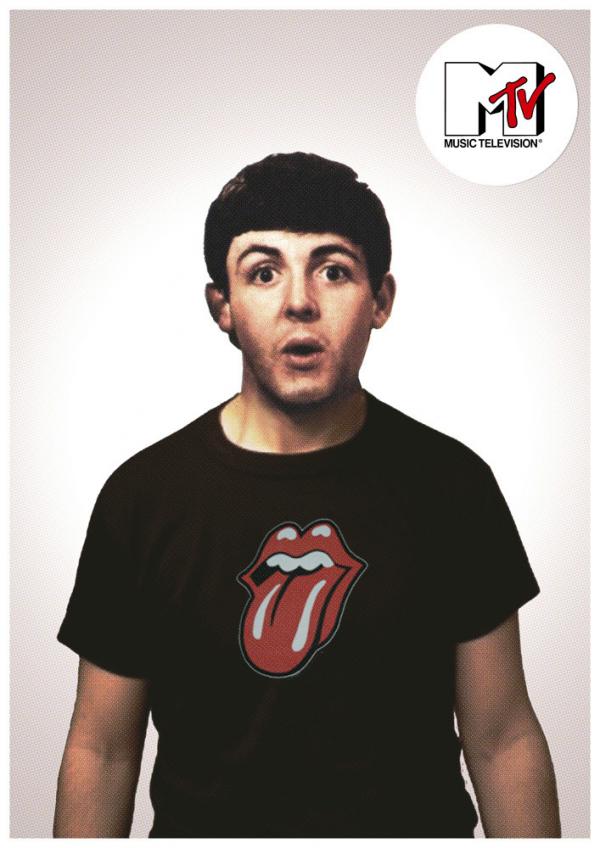

As I’ve written, John Lennon was my favorite Beatle growing up—for all the reasons we love John: his intelligence and wit, his directness, his unique gifts with words and music, his sense of larger purpose in the world and ability to inspire. Plus, I felt that as a young creative person in the middle of nowhere trying to make a black-and-white life turn into glorious Technicolor, John Lennon had specific things to teach me. Plus, his difficult beginnings were similar in some ways to my own, and so we shared that fierce desperation to make it, no matter what. Happy people don’t aim for the “Toppermost of the Poppermost,” and normal people don’t think they just might be able to get there.

So I came by my John-love honestly, and for the first decade or so of my fandom, he was my guy. But starting in my thirties, that began to change. Now, as a middle-aged creative person, facing middle-aged creative person problems—professional ones like how to stay fresh and enthused and how to mature gracefully in an artistic sense, as well as personal ones like family and aging, death and dying—the Beatle I look to most regularly is Paul. He’s the one with the most to teach me now. John Lennon can show you how to become, but Paul McCartney’s a much better guide on for how to be.

Oh sure, George has his appeal, when I’m fed up and considering a mountaintop or a monastery. But George, like his main Beatle pal John, was a fundamentally unquiet fellow. He was, first of all, excessive; with George, as with John, it was either orgies or celibacy. He had competing drives, and couldn’t resist either. I think George was probably getting close to resolving this conflict (age gives as it takes away), but there’s still a fundamental dissatisfaction there—a wishing that things were better, different, more than they are. I get no such sense from Paul McCartney; I never have.

Think of it: The world gave four men—boys, really—everything they could ever dream of. Two of them took those gifts and were content, and have lived to ripe old ages. Two were never content—all they got, seemed to stoke more wanting—and died young. 58 is young in my book; it’s only eight years away, the span from 1962 to 1970.

It’s not just that at 50 I’m older than John ever was, and rapidly approaching George’s Launch Date, too; it’s also that Paul seems to have been uncommonly successful at navigating the stuff that so few rockstars can pull off. He’s continued to work without becoming an oldies act (sorry Ritchie), paid his taxes, never lost his money, and never shows up drunk, bandana askew, in some strip club down by LAX. With a few hiccups aside, Paul’s family life seems to be pretty good, too—especially when judged against others in music and showbiz.

Go read Sticky Fingers and tell me who’s life you’d prefer, Jann Wenner’s or Paul McCartney’s. Paul’s a control freak? Paul’s materialistic? There’s more perfidy on every page of that bio than all the supposed dirt we have on Paul. And Wenner, like his pal Lennon, was living a lie for most of his adulthood, just so he could stay in the good graces of the public. Not so with Paul, and that’s why the cool kids hated him. He didn’t have to wreck himself to be famous, nor did he let being famous wreck him.

The very things that the Rolling Stone crowd castigated Paul for—his “uncoolness”—are the things that, in the end, make for a happy life. Stability; focus on work and family; an ability to relate to people of different ages and stages; pleasure in the little things like (famously) riding a bus. Rock and roll in the Sixties was so often about breaking away from the family, doing your own thing, remaking the world in one’s own image. That’s why Lennon is such powerful cultural shorthand for that era, and Paul isn’t. Lennon, especially in full-beard guru phase, evokes all those things so powerfully. Paul, at that time as now, evokes Paul.

This is perhaps why we talk less on Dullblog about Paul than we do about John. John Lennon is a leaping-off point to lots of stuff—that’s how he lived, and that’s how he liked it; John wanted you to think about “peace” so you wouldn’t look too closely at him. And the contemporary press was happy to oblige, because John Lennon was a rolling controversy machine. Then all that good copy was stopped in the cruelest, saddest, suddenest way; you could fill an entire blog on John’s “what might have been.” Whereas writing about Paul is like writing about the MacIntosh computer. There is only what is; there is only what happened. Yes, it changed the world; yes, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing right now without it; but a successful is, is inherently less dramatic, less interesting, than a tragic might’ve been.

“What would Paul McCartney do?” At 12, when I thought about how best to be a person, I would frequently look to John Lennon. Now, nearly forty years later, I look to Paul. I suspect I’m not alone in this, which is why I took the time to post.

I loved this, Michael.

One comment you made about Paul in your “John Was My Favorite Beatle” piece, stood out to me.

“But I’d argue that part of why a certain type person loves Paul best is precisely because he is stable.”

I think that is true. At least for myself.

My childhood was definitely unstable. Consequently, I have made choices in my adult life to make things as stable, and calm as possible. So, subconsciously, I may have chosen Paul as my favorite, because he projected warmth, stability, openness. I say subconsciously, because as a teen, I wasn’t self aware enough to realize that.

I also was/am a people pleaser, like Paul, so that may be another reason I chose him. But again, that’s retrospective.

I love Paul for all the reasons you stated so well, but also because Paul loves to make music, and to make his fans happy with his music. I’ve seen him 3 times, and it is so apparent how much he loves performing. He is in his element, and exudes joy. He is energetic, and gives 100% to his performances. That does not go unnoticed, or unappreciated, by his fans.

So, I love Paul because he is stable, a good father, husband, and person, but also because he is the ultimate music man.

ROCK ON PAUL!

@Tasmin, people who strike a chord in massive audiences are, I’m convinced, archetypes. There is something about that person that makes sense to millions of strangers. In addition to the music, what made The Beatles so much more powerful than their contemporaries was the fact that they had several powerful archetypes in the same group–and if you ask me, what made those people into archetypes was the alcoholic family matrix.

.

According to what I just found on the internet, there are six typical roles. The Beatles, plus Brian Epstein, fit into five of them.

.

John is the addict. “Addicts function and fulfill their responsibilities to varying degrees. For most, addiction progresses as the quantity and frequency of their drug or alcohol use increases. Drugs and alcohol become the primary way the addict copes with problems and uncomfortable feelings. Over time, addicts burn bridges and become isolated. Their lives revolve around alcohol and drugs – getting more, using, and recovering. They blame others for their problems, can be angry and critical, unpredictable, and don’t seem to care about how their actions affect others. One can also substitute other forms of addiction or dysfunction (sex addiction, gambling, unmanaged mental health problems) for drug or alcohol addiction and the dynamics are virtually the same.”

.

Paul is the hero. “The hero is an overachiever, perfectionist, and extremely responsible. This child looks like he has it all together. He tries to bring esteem to the family through achieving and external validation. He’s hard working, serious, and wants to feel in control. Heroes put a lot of pressure on themselves, they’re highly stressed, often workaholics with Type A personalities.” Sound like Paul?

.

George is the lost child. “The lost child is largely invisible in the family. He doesn’t get or seek attention. He’s quiet, isolated, and spends most of his time on solitary activities (such as TV, internet, books) and may escape into a fantasy world. He copes by flying under the radar.” Sound like The Quiet One?

.

Ringo is the clown. “The mascot tries to reduce family stress through humor, goofing around, or getting into trouble. He’s seen as immature or a class clown. Humor also becomes his defense against feeling pain and fear.” Ringo, the clown, was the one all of them could always talk to.

.

And Brian is the enabler. “The enabler tries to reduce harm and danger through enabling behaviors such as making excuses or doing things for the addict. The enabler denies that alcohol/drugs are a problem. The enabler tries to control things and hold the family together through deep denial and avoidance of problems. The enabler goes to extremes to ensure that family secrets are kept and that the rest of world views them as a happy, well-functioning family. The enabler is often the addict’s spouse, but it can also be a child.”

.

It’s very likely that all of these roles were practiced by each Beatle in his own family before the group came together. And this is what bonded them so tightly, much more tightly than normal. They called each other “brothers,” and in a very real sense they were. Brian saw The Beatles and, yes, he saw them as sexual objects, but he also saw that he could do a job for them, a job he craved to do.

.

When John’s enabler Brian died, he felt a very real and understandable fear: who was going to clean up his messes? What would happen the next time he went and did something reckless or impulsive? John had to find another enabler–another fixer, another person to save him from consequences–and he eventually found one in Yoko. But Yoko wasn’t part of the family; the family threatened her. So John was caught between the person he felt he needed, and all these others who played roles. Painful for everyone.

.

I’m also a people-pleaser, and people-pleasers often go into entertainment, which is pleasing people for money. There’s nothing wrong at all with these labels, or even these behaviors (within reason). Paul is a charming, wonderful, talented fellow who has probably been a hero since before he could talk. Then, when his mother died, it went into overdrive. It’s plausible that Jim was an addict, Mary was the enabler, Paul was the hero, and Mike was the scapegoat. When Mary died, the family system went kablooey, and Paul kicked all the hero stuff into another gear.

.

This also fits the conflict between Jim and John — each wanted that hero.

This makes such sense, and helps explain why the fascination with the Beatles endures to this day

Michael, your explanation of what McCartney specifically has to offer those of us who are no longer young aligns with my own feelings on the subject. Paul is my Beatles co-pilot in part because his music deals with the sheer dailiness of life in a way that acknowledges darkness without succumbing to it.

.

One of my favorite McCartney solo tracks is “Somedays,” because the verses articulate how our feelings about practically everything inevitably vary day to day, while the chorus reasserts the lasting value of love.

I’ll always love McCartney because of his gift for melody.

People have compared him to Mozart, but I think he’s more like the unschooled street musicians that guys like Mozart stole their melodies from. Folk musicians connecting directly to the people, while the classical boys stood in the back taking notes.

I’ve probably said it here before, but when I hear a McCartney melody for the first time, it’s like I’ve known it my whole life (or in a previous life), but have forgotten it, and am now being reminded. His music makes perfect sense structurally. Unforced. Natural and flowing. I love his chord progressions. And I believe he is the most melodic bass player in Rock music. I often find myself humming along with his bass parts on Beatle songs and his solo stuff.

I think he was the heart of the Beatles. (John the brain, George the soul, Ringo the body? Just spitballing here…)

I love this blog. So glad the community is back in action. Great discussion as usual.

This sort of thing is why I love Paul: https://metro.co.uk/2019/08/20/sir-paul-mccartney-reveals-literal-penny-pinching-tip-make-guitar-picks-10601934/.

There’s a ton of individualism and rebellion there, but with a quirky confidence that lets him stay under the radar and not make a target out of himself, needlessly. It’s that spirit as much as John’s iconoclasm that makes the Beatles.

This is spot on, Michael.

I love the penny story! Paulie is definitely quirky!

Great break down of their roles, can definitely see that in the family lives and the band.

I’ve only seen Paul live once, it was a long time ago now, but like Tamsin, I remember being struck by just what a natural he was and what joy he exuded just in performing. It’s this huge stadium and yet still felt so warm and welcoming because he’s able to make such a connection with the audience. It’s very authentic.

Hi, everyone, I wanna share some of my thoughts with you:

.

When I was a teenager, my favorite Beatle was John, partly because being a Lennon girl seemed to be cooler and partly because, like most teenagers, I was full of insecurity, resentment, and other negative feelings, and his music adjusted to my way of seeing and feeling life … I didn’t realized that it used to take me to a darker place.

.

On the other hand, Paul used to be my guilty pleasure, I liked him a lot, but wrongly I was not convinced of his talent … I really didn’t know how to appreciate him.

.

Once I reached adulthood, my verdict was, –based only on the emotions that their compositions evoke–, that is more what Paul’s music can bring to my life than John’s … I want to live in a world full of light, love, happiness and that is what Paul is able to radiate in such a natural and congruent way.

.

I avoid comparisons between them as musicians, instead I prefer to gauge them through their strengts against others in a global context. The result is that John was a great lyricist, however, there were many others even better, such as Dylan or Leonard Cohen (although he is not a rocker) In the case of Paul, he is so talented in the music department, with a natural flow of good melodies, he is undoubtedly the Master of Masters, far ahead of their competitors.

.

And that’s how I try to explain to you, in words, how I went from being Team John to Team Paul.

.

Es interesante pensar cómo relaciono mi yo inmaduro con John Lennon, y mi yo maduro con Paul McCartney. De verdad me gustaba mucho Lennon, hasta que me di cuenta que me deprimía mucho con su música, sobre todo la solista, me ponía en modo gris.

.

Que Paul fuese un gusto culposo se relacionaba directamente con el estigma de que era el Beatle bonito, que escribía canciones azucaradas y facilonas. Fui una víctima más de las críticas sesgadas de los periodistas y columnistas del pasado, hasta que entendí que el valor de la música está en lo que ésta te hace sentir, mas allá de las opiniones de los demás.

.

Cuando reconocí que la música es el idioma universal, transité fácilmente de Lennon a McCartney porque pude aceptar que con versos o sin ellos, sus canciones se sostenían por sí mismas, que el mensaje de igual forma llegaba a las personas, de manera tanto o más contundente que una buena letra.

.

Es solo una opinión, mi manera de verlos a los dos.

This is interesting, Alejandra. Thank you.

.

It’s important to remember when comparing John to Paul (or Dylan or Cohen, and so forth) that he died at 40. He was not finished as an artist. We’re really left comparing the work of a young man active for 18 years to people active for 50+.

.

“It’s important to remember when comparing John to Paul (or Dylan or Cohen, and so forth) that he died at 40. He was not finished as an artist. We’re really left comparing the work of a young man active for 18 years to people active for 50+.”

.

Ok, that’s totally reasonable, sounds fair. Thanks for the observation.

Yes, John died young. No one is perfect and we all get side tracked, but John’s solo years is an EXCELLENT example of how none of us know the future. He and George too wasted a lot of the solo and air time, too much of it bitching to press about Paul, and both verbally resented having been in Beatles which they each welcomed to begin with. They each could have left in 66 after touring but admitted didn’t have guts to. They stayed on distracted in over drug use and meditation and got increasingly resentful of Paul’s lead probably because of John’s depression and acid eating binge, then later yoko distraction and John’s heroin stupor.

Solo in the years they did have John and George could have spend time producing more music and improving their skills, as everyone can instead of wasting time fretting publicly over Paul over old grudges they should have addressed in private. I remember it got so bad that the regular press, not the rock press John and George fanboys, but the regular press noted they were immature and wondered how it had gone unnoticed. John tragically wasted time on a drunk long weekend of several months and produced his rough voice rock n roll oldies music album, then wasted five years retiring only back by a B52 song and, per yoko assistant, ironically after all John’s Paul dissing, Paul’s coming up electronica song.

George likewise retired in his career, only coming back when dying. They are a great example of how life can be short, as we never know. They each had great talent but were too openly negatively focused on another way too long, and per yoko John was obsessed with Paul’s solo, and repeatedly played it, kept up with his chart and financial success. Right up till almost he was dying, George was giving his Paul grudge interviews, and he had the same grudge tendency with sister Louise who helped him in Beatles but she learned somehow he was in Sinai hospital, made amends, a brother George out with eight years never made amends with, Paul went to him when dying and set him up in his home for comfort, causing some evil PIDers to accuse Paul of killing him.

John and George each overly repeatedly negatively focused a long time on another as noted by their repeated interviews over a course of several years more than they seemed to emphasize their own music and each retired and came back just before the end. None of us ever know how long we will have. Also, John’s and George’s music and artistic vision could be but was not always expansive but sometimes contracted, other times recycled musically and thematically.

Paul is the Unknown Beatle. So much is discussed about him only in relation to other people. He is the foil, not the individual, either the happy, stable ‘ordinary’ man or the perfectionist control freak. I think he is the most misunderstood of the four by far. There appears to be so much more conjecture and cheap negative assumptions about Paul in my opinion, and I don’t think there will be a clearer picture of him until after his death. What often seems overlooked is the extent to which John and George’s wives and girlfriends (and their sons) have disclosed about them, the people closest to them, aside from their fellow Beatles. This has not happened with Paul. Had Linda outlived him she may have had something she wanted to say about Paul, but sadly she died early. Jane was wounded and she will never talk about Paul. Heather has had some sort of non-disclosure agreement slapped on her. Nancy? Perhaps – if Paul has filled her in about everything since the day he was born.

I don’t know about this thing about his family being addicts. Mary was a heavy smoker and it killed her, that’s for sure. Being a midwife up until the mid 50s wasn’t always the joyous occasion of bringing a new life into the world. Mary must have encountered some horrendous and tragic circumstances in her work in war damaged and poverty stricken Liverpool. Jim was called up for firefighting duties during the war. He must have sighted burnt and crushed bodies, which trained and experienced responders find difficult to stomach, let alone civilian aiders finding themselves in a situation they didn’t ask for. Perhaps neither of them had an outlet for stress. It’s possible the boys were raised with the ‘don’t complain, there are people far worse off than you’ style of parenting.

Nothing is ever mentioned (unless I missed it) about Paul being hospitalized for several weeks as a child for rheumatic fever, a serious illness that can have neurological consequences. It’s weird that Paul said the masters at school yelled at him because of his mirror writing. The very term masters implied that this happened during his Institute years, not at age 5-8 years when letter reversals are more common. Paul is so secretive – he starts something, then clams up completely.

Ultimately, he is the person we see but don’t see.

@Alejandra: “When I was a teenager, my favorite Beatle was John, partly because being a Lennon girl seemed to be cooler.”

Still is for me.

This makes me think of something I noticed recently about the way that John and Paul sang/sing, and how it relates to the fans.

Paul seems to have always been able to protect his voice, even when doing his “little Richard” he maintains a measure of control. You can easily find recordings of John’s voice blown, but even when Paul purposefully tired his voice for Oh Darling, it’s smooth in the smooth parts. And lots of fans object to this. They say that Paul’s performance isn’t as real and raw as John’s.

They’re not exactly wrong, but it’s an interesting demand: that an artist should sacrifice everything, all personal protections, for the sake of authenticity. I think this is related to the complaints that Paul is inauthentic in interviews.

The more I learn about him, the more I’m blown away by how personally and artistically successful Paul has been. He’s by no means perfect, but to have such a stable family life as an ex-Beatle is really remarkable. And artistically: as someone said on another forum recently – everyone agrees that there are some clunkers in his musical output, but there really isn’t agreement which songs are the duds.

So John was the musical equivalent of a Method Actor, one who sacrificed his body for his art. They believe that living and breathing the character brings authenticity to the role, as do many voting members of the Academy.

I think this is a very accurate reading of John in particular, but all the Beatles, and puts their phenomenon in a context they often did themselves (as in Anthology) — The Beatles as a continuation/broadening of cultural things like Brando/Dean, etc.

Paul is love and joy – he really was the epitome of what The Beatles dream was about. Paul is the dream!