- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

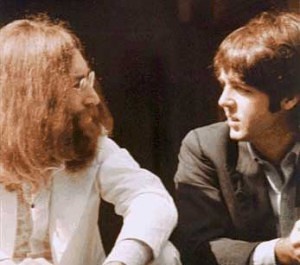

John and Paul face off, 1969

Some thoughts about an aspect of Lennon’s and McCartney’s solo music, prompted by some recent re-listening. — Nancy

After the break up, each Beatle pursued his own musical sensibilities pretty much unchecked. Here I want to look at a difference between Lennon’s and McCartney’s solo music that hasn’t gotten much critical attention: Lennon’s tendency to write songs of rejection and McCartney’s tendency to write songs of invitation.

Since we’re considering Lennon and McCartney, everything is maddeningly complicated. Presenting them as opposites or complements overlooks all the ways their music overlaps, and focusing on a single theme they treat musically necessarily involves disregarding much of their work. This, then, can only be one angle on these complex musicians. But overall it’s true that as a solo artist Lennon wrote more songs about holding people at bay and McCartney more songs about drawing them in.

Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band is essentially about rejection – the experience of being rejected (“Mother”), and the action of rejecting (“God”). “God,” in particular, is a litany of things Lennon doesn’t believe in. What he does believe in is covered in two lines, and circumscribes a very small area: “Yoko and me / And that’s reality.” Regaining sanity after the band’s breakup seems to require shutting out most of the outside world.

Imagine softens this a bit – but only a bit. The title song offers a vision of the whole world becoming one, but makes it clear that an entrance exam must be passed: “Imagine no possessions / I wonder if you can.” The listener is addressed as one standing outside the beliefs the song articulates, and isn’t so much invited to join in as extended a possibility overlaid with doubt: “I hope someday you’ll join us.” This dynamic – “we” are already imagining no possessions, no heaven, etc., and are wondering if it might be possible for you too someday – has for me always rather cut against the grain of the song’s apparent intention.

Not so in Imagine’s “Gimme Some Truth,” Lennon’s great song about rejecting toxic politicians and power brokers: nothing diminishes this denunciation of dishonesty. And in the single “Instant Karma,” my favorite Lennon solo song, he manages to reject behaviors without rejecting people, and without softening his call for positive change.

But when Lennon moves from addressing people as a group to writing about intimate relationships, his songs tend toward extremes of dependence or rejection. Imagine’s “Oh Yoko” is one of the most intense depictions of neediness ever committed to vinyl (“In the middle of a shave I call your name”). The same album’s “How Do You Sleep?” is an astonishing enactment of absolute rejection, as Lennon acidly derides McCartney’s life and music.

There’s very little middle distance in Lennon’s solo songs, if I may so express it. It’s hard to find many people in them other than a specific few being loved or hated and the multitude being talked to as a group (“Power to the People,” “Working Class Hero,” etc.). And this doesn’t change much over the course of his solo career. Double Fantasy’s “Woman” and “Just Like Starting Over” are clearly about Yoko Ono, while “Beautiful Boy” is addressed to Sean Lennon. And part of setting things to rights in “Cleanup Time” is banishing bothersome people from the charmed circle: “No friends and yet no enemies / Absolutely free / No rats aboard the magic ship / Of peace and harmony.”

McCartney expresses rejection musically too, but much more rarely and ambivalently. Ram’s “Too Many People” criticizes Lennon for “preaching practices” and taking his lucky break and breaking it in two, but adds “This is crazy and maybe / it’s not like me.” Only in this song and the same album’s “Dear Boy,” directed at Linda’s ex-husband, does McCartney come anywhere near the sharp personal criticism Lennon takes to the limit in “How Do You Sleep?” and Walls and Bridges’ “Steel and Glass” (which targets Allen Klein).

Much more typical of McCartney are songs that address the middle distance, that invite hearers to participate in something the speaker is also doing or enjoying. “Rock Show” on Venus and Mars, “We’re Open Tonight,” on Back to the Egg, “Take It Away” on Tug of War, and “Dance Tonight” on Memory Almost Full are all songs inviting the listener to a party. Partly this kind of song reflects McCartney’s identity as a performer: he needs an appreciative audience in a way Lennon didn’t.

Beyond these let’s-have-fun-together examples are a number of other invitational McCartney songs. Most famously, “Let ‘Em In” advises the listener to open the door to a laundry list of people seeking admittance (Sister Susie, Auntie Jin, Martin Luther, etc.). This theme gets a more serious treatment on songs like “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” (London Town), “Somebody Who Cares” (Tug of War), and “Put It There” (Flowers in the Dirt), all of which urge the addressee to engage with the speaker instead of retreating from human contact. “Fine Line,” from Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, even invites someone who’s been rejected to return: “Come home brother, all is forgiven / We all cried when you were driven away.”

Certainly one can’t conclude on the basis of such invitational songs that McCartney is actually more friendly or forthcoming than Lennon; despite his public persona, McCartney seems more guarded and protective of his privacy than Lennon was. But it does seem fair to conclude that for McCartney loneliness and its alleviation have a social dimension they don’t typically assume for Lennon. Lennon’s magic ship includes “no friends and yet no enemies,” only a very select crew. Contrast that with the mainly-McCartney-written “Yellow Submarine,” which hyperbolically declares that “Our friends are all aboard / Many more of them live next door.” Indeed, several of McCartney’s good-time invitations underline their all-inclusiveness: “We’re Open Tonight” asks the listener to “bring all your friends” and repeats “come one, come all.” And after stating “you can come on to my place if you want to,” “Dance Tonight” emphasizes that everybody is going to dance and have a good time, and “everybody” appears more than twenty times in this relatively short song (yes, I counted).

I suspect it’s mainly personal temperament that determines whether you prefer Lennon’s keep-em-out or McCartney’s let-em-in songs, and to what extent you appreciate both. To fully enjoy Lennon’s songs, you have to see yourself as one of the people he wouldn’t exclude. To fully enjoy McCartney’s, you need to be feeling playful (the come-to-the-party songs) or potentially vulnerable to loneliness and exclusion (the reassuring songs).

I like both, but confess to coming down on the McCartney side more often (this will be no news at all to regular readers of this blog). When I hear “Let ‘Em In” I think of the stories of McCartney knocking on Lennon’s door at the Dakota and being turned away. I can’t support with facts my hearing a reference to Lennon in the song’s “brother John,” but I hear it anyway and hope it’s really there. Hearing it there accords with my feeling that shutting people out should be done sparingly, despite the risks entailed by letting them in.

You have made many excellent points. When John&Paul collaborated, their differences blended (“It’s getting better all the time/ it can’t go no worse”) but once the collaboration ended they were free to explore their opposites.

I believe John’s famous “lost weekend” was a lost opportunity to repair his friendship with Paul. May Pang tried to help, but John was too distracted… I recently saw the Harry Nilsson documentary, and it put things in perspective for me. So many musicians came forward and admitted they had lost weekends with Harry; it was not unique to John. If Nilsson had been more of a grownup, then maybe John would have been more focussed on patching things up with Paul.

– Hologram Sam

Sam, I saw that Nilsson doc, too, and Harry Nilsson’s problem wasn’t that he was immature, it was that he had substance abuse problems. As did Lennon; and Ringo; and Keith Moon; and that whole cast of characters.

Learning about alcoholic families, schema and behavior patterns is a HUGE key in understanding the people in this story. Not to hijack the thread, but just in case it rings as true to you as it does to me:

http://gods_mark.tripod.com/Roles.html

From left: Paul, John, George, Ringo.

Michael, thanks for that link. As an adult child of an alcoholic (my parents passed away in 2000) my childhood was… challenging to put it mildly. I was the youngest in a family of three kids, my father drank and terrorized me, and my mother denied everything. My two siblings were ten and eleven years older than me, and fled the house while I remained trapped.

Maybe “grownup” was the wrong word to use about Harry. I think I was referring to the club-hopping hi-jinks, the heckling of the smothers bros., etc. My father was a stay-at-home drunk, he was not one to party with his pals, as he didn’t have any.

I guess the point I was reaching for is that despite the stylistic and conceptual differences of John&Paul, they blended perfectly, and if Lennon hadn’t followed Harry, he might have directed his attention more productively.

I’m not bashing Harry here, I collected his records in highschool; he was part of the soundtrack of my adolescence. I actually cried at the end of the documentary. Maybe as much for myself as for Harry.

– Hologram Sam

Thanks for sharing that, Sam. I too grew up in an alcoholic family, so I know exactly what you’re talking about. And it informs my Beatle thing in so many ways. For example, addicts can be really charismatic–especially if you grow up in that–and if you know that, Julia Stanley’s life makes much more sense; how she could’ve been both really winning and talented, and also a mess. How she could alternatively love her son and act callously towards him–which then made John work up his own charisma to charm her…

Like you, I primarily felt sad for Harry–as I do for John. Beautiful, brilliant people hobbled. If John had lived, it would’ve been interesting to see if he would’ve taken advantage of the new tools available to people scarred by substances.

One must remember that Lennon (and Nilsson) grew up in a time and place that didn’t treat booze with any kind of respect or understanding. Drinking was just what people did. To be a rock star in 1974 was to party, and if you had an inherited tendency to overindulge, or get violent, or act out, that’s what happened.

Much of what bugs people about McCartney is a certain “people-pleasing” aspect they see in his character–that, too, is straight out of the alcoholic/codependent matrix.

Of course you can go too far with this kind of supposition, but I’ve found it to be illuminating and compassion-inducing, rather than the opposite.

Nancy, I’ll post some comments about your post when I get more time today or tomorrow.

But; Did you say the great review of Ram in the AV Club (which gave Ram an “A”? And even more important, Pitchfork today gave the Ram reissue a huge (for Pitchfork) 9.2 out of 10 and called it a “best new reissue”!!!! And Rolling Stone (publishing only a 2-sentence review) actually gave it 4 and a half stars!

YES! Q Magazine can stuff it. 🙂 I’m going to savor this. I doubt any of Paul’s other reissues will EVER get this kind of acclaim.

— Drew

Good points about both men and the alcohol issue. I too saw that Nilsson documentary, and I actually wished that Una Nilsson had talked more about what it was like being with him (I can understand why she didn’t; she and the kids deserve some degree of privacy), but he seems to have somewhat gotten things together with her.

Michael, that’s a good point about McCartney’s people-pleasing. He cares about audience reaction and needs direct feedback from the crowd (hence, I think, his devotion to performing live).

But wasn’t Lennon, in some ways, also pretty people-pleasing? In those many hours of interviews he was giving Wenner et. al. exactly what they wanted. I’m not saying that was Lennon’s primary motivation for giving interviews or saying what he did, but that he had to be aware of that dynamic.

Drew, thanks for mentioning the Pitchfork review of “Ram” –I hadn’t seen it, and it’s great! It’s so smart and well-crafted it makes me jealous. That Jayson Greene can write.

Link here, for those inclined:

http://www.pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/16651-ram/

Of course I love that he makes the same link between “Ram On” and Lennon’s “Hold On” that I do (last summer, in the “Ram’s Resurgence” piece). But everything he says about the darker edges of “Ram” is brilliant, and this paragraph about “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” is perfect:

“Critics hated “Uncle Albert”. “A major annoyance,” Christgau opined. Again, from the current moment we can only plead ignorance, assume that some serious shit had to be going down to clog everyone’s ears. Because “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” is not only Ram’s centerpiece, it is clearly one of McCartney five greatest solo songs. As the slash in the title hints, it’s a multi-part song, starring two characters. To put its accomplishments in an egg-headed way: It fuses the conversational joy listeners associated with McCartney’s melodic gift to the compositional ambition everyone assumed was Lennon’s. To put it a simpler way: Every single second of this song is joyously, deliriously catchy, and no two seconds are the same. Do you think early Of Montreal, the White Stripes at their most vaudevillian, or the Fiery Furnaces took any lessons from this song?”

And it’s nice that “Rolling Stone” finally coughed up the 4/12 stars the album deserves, even if they couldn’t bring themselves to say more than two sentences about it.

Wow, that’s a great review of RAM, Nancy, thanks for pointing us to it.

“People-pleasing” in the Adult Children of Alcoholics sense I was using it, has a specific meaning. It’s putting other people’s needs and wishes before your own as a coping mechanism. It’s wanting people to like you so much, you act against your own best interests and/or damage yourself in the process. Paul strikes me as a people-pleaser–a compulsive smoother-out–a person who will tell you what you want to hear no matter what. John does not.

Michael, I see what you mean about people-pleasing, given that definition. And that helps explain why McCartney insists that EVERYBODY come over and have a good time. And you’re right that Lennon isn’t people-pleasing in quite that way. “Yoko and me / And that’s reality” — and the rest of you, go deal with it.

Credit for pointing out that great review of “Ram” should go entirely to Drew, BTW.

I just got recommended this blog, and I’m liking what I am reading so far.

One can not have enough of beatle-obssessive readings.

I would just like to add on the subject that I think I read somewhere that Lennon appears on Let’em In, but not where we use to think. “Brother John” would do mention to Paul’s brother in law, Linda’s brother (“Sister Suzie”). But it seems that Lennon would be the elusive “Martin Luther”. Supposedly, they would have called him that way in those years, because of the many causes John(and Yoko) used to advocate for.

Luzeeanabeat, glad you’re enjoying the blog. Interesting about John possibly being “Martin Luther” in “Let ‘Em In.” I guess either way, John shows up in the song as someone being invited in.

“This dynamic – “we” are already imagining no possessions, no heaven, etc., and are wondering if it might be possible for you too someday – has for me always rather cut against the grain of the song’s apparent intention.”

I just read this sentence 27 times and I still don’t get what your trying to say. Could you explain? Thanks

Michael Gerber said…

“People-pleasing” in the Adult Children of Alcoholics sense I was using it, has a specific meaning. It’s putting other people’s needs and wishes before your own as a coping mechanism. It’s wanting people to like you so much, you act against your own best interests and/or damage yourself in the process. Paul strikes me as a people-pleaser–a compulsive smoother-out–a person who will tell you what you want to hear no matter what. John does not.———-

Hello! Sorry, I really don’t understand what you’re saying here. I mean, Paul wasn’t the child of alcoholics, was he? Did you suggest he was co-dependent?

Anyway, Paul did say unpopular things. What about the LSD confession interview in 1967? The anouncement on the break up in 1970? the lawsuit?

I think, Paul in public stopped to adress certain issues because too often he got misinterpreted, or someone called “revisionism”.

Craig, sorry for the monster sentence — should probably have been two. Here’s an attempt to clarify:

In “Imagine,” the speaker is presented as already having succeeded in imagining no possessions, God, etc. The repeated “it isn’t hard to do” reinforces this.

The hearer is positioned as being invited to do the same imagining, but there’s doubt attached to this: “I wonder if you can” and “I hope one day you’ll join us.”

And it’s this positioning of the speaker over and above the hearer that makes me uncomfortable. It seems to me to undermine the message of everyone’s becoming one.

Make sense? If so, let me know what you think.

Anon, I have no idea whether or not Paul’s the child of an alcoholic, but because I am, that language has always explained Beatle-dynamics quite efficiently for me.

Substance abuse is very prevalent, and the behaviors caused by it, once introduced into a family, can persist over generations. And in a lot of cases, they are exaggerated versions of healthy behaviors–so you can’t really tell what somebody’s family dynamic is without knowing them personally, very well. I wouldn’t want to tar any of our beloved Beatles with that brush, not at a more serious level than sports-radio conversation.

Thanks for the clarification, Nancy. Very interesting, I love hearing all our differing interpretations of songs we’ve heard a million times. I have to be honest that I’ve never quite thought about ‘Imagine’ in the context of John seeming somewhat excluding in the song.

‘Imagine’ is a song that can, and has been, endlessly analyzed. I think there are some great comments that John makes, and also some pretty horrid, if pretentious ones.

No political or geographic lines helping to divide us and provoke hostility: I can get down with that.

No religion giving the world a myriad of reasons to hate each other: ummm yes, where can I sign up??

No individual possession of objects and/or land: no thanks. One wonders if John really knew what he was saying with this line. Yes, it may sound good and it fits nicely with syllables and rhyming considered, but it really jumps out at me. Did he truly believe this? I would venture to guess with almost certainty that he did not. Now, you may say that he didn’t believe a girl named Lucy was dancing in the sky, but ‘Imagine’ takes itself so seriously, that the listener is therefor directed to take it in a serious tone. At no point in his life did John ever portray a leaning towards a communist/Marxist lifestyle. Yet he throws this line out there like this is the ultimate goal for humanity. It’s always bothered me and led me to conclude that John put this line in because it simply sounded too good to be discarded.

Nice article. I’ve always found Paul’s “Let Me Roll It” to be the ultimate invitation/make up song to Lennon. It’s got a lot of Lennoneque instrumentation. The production sounds straight out of Phil Spector. The lyrics are almost a positive flipside to “Cold Turkey”. There’s even a stumbled beat near the end and full-wailing scream as well. To me, it was McCartney responding to and offering to end the very public musical and in the press finger pointing that had been going on between them since the break up. I’d appreciate to hear everyone’s thoughts on this.

In my opinion, the Beatle experience turned all four men into introverted characters.

Paul was every bit as insular and introverted as John. Both men married women who they made their “everything”—best friend, lover, collaborative partner. Such relationships do not leave room for close friendships.

I would bet Paul is every bit as dependent and jealous as John was. Consider the song “Friends To Go,” a song that one could speculate was about his relationship with Heather Mills. If the song is autobiographical, Paul is hiding out in his house, waiting for Heather’s friends to leave so he can have her all to himself.

I actually agree with JR Clark on Paul being introverted. In fact, I’d say Paul is what I would call an extroverted introvert. Sure he loves to be on stage — but that’s an environment he controls entirely and gives only a slice of himself to the public.

But in the vast majority of his daily life he is happy hiding away with his wife and kids, a small circle of friends. Heather Mills complained how few friends he actually had and how happy he was to be at home. Paul always said Friends to Go was about George but I think Paul’s covering for himself there. He didn’t want to admit that HE was the one hiding away from his wife’s friends. And I don’t think it’s because he wants his wife to himself. He sings in that song, “I’d prefer they didn’t know.” He’d prefer they didn’t know much about HIM.

That reminds me of another song of Paul’s that I’ve always thought is very autobiographical. It’s “Nobody Knows” off McCartney II — and he sings there “nobody knows and I like it that way” and he adds “even you honey,” and he was married to Linda at that time. I.E. there are things about himself he doesn’t want her to know either.

I think the extreme fame turned Paul into an introvert. That’s how he copes with the pressure of living under a microscope and having everything you say and do get blown out of proportion.

Huston: Yes, I totally agree that Let Me Roll It was a plea and an olive branch. It’s just too bad that John was still so stubborn and angry at Paul that he refused to accept it, other than superficially I mean. Sure he stopped biting Paul’s head off in interviews for awhile, but they never truly ironed out their problems.

— Drew

Interpretations of songs are interesting. Please don’t laugh, but because “Friends to Go” was written in somewhat George’s style, I tend to believe Paul would’ve wished to have been invited to participate in the Traveling Wilburys sessions. Roy Orbison and Bob Dylan were his heroes too.

I agree with “Let Me Roll It” could be written with John in mind.

Huston, I like your analysis of “Let Me Roll It.” I also hear it as at least in part an invitational song to Lennon, but I never thought about the stumbled beat and the wailing scream at the end as mirror images of “Cold Turkey.” Very interesting.

J.R., I agree that McCartney was/is dependent in much the same way as Lennon. They just express it somewhat differently in music, and McCartney seems to need an audience’s response more. I don’t so much think that the Beatles made them introverted as that it made each of them protective of what privacy they could hold onto.

And Craig, I think of Lennon saying of “Imagine” in the years after its release that it was “just a song.” He knew he wasn’t living by everything in that song, and that it was just about impossible to do so. I respect him for publicly acknowledging that, but the preachiness I hear in the song itself somewhat grates on me.

Did John ever comment on ‘Imagine’ with regards to his intent and the messages the song sends out to the listener? I don’t remember seeing anything, but always a chance I’ve missed it.

Yes, I agree Nancy, ‘Imagine’ can be quite grating. But, if you decide to simply listen to the nice melody and John’s beautiful voice asking and hoping for us to all get along, it can be a satisfying experience for the listener. Try to disregard its preachiness, as you say, and the fact that it is somewhat (if very) hypocritical.

There has been a decent amount of backlash on this song, some of it deserved. Recently this song came on the radio and my friend, who is also a Beatle nut, groaned and said he hated it. I asked him why and his main complaint is that it’s overplayed. Fair enough, I tend to agree. But I wish people would just look at the song as what it is (and not do what I did a few comments above): a man singing a song that strives for a happier, more peaceful world. I see no harm in that.

Craig, online I’ve seen references to Lennon saying “It’s just a song, man” about “Imagine” — apparently in the documentary film about the making of the album — but I haven’t seen the film, and don’t know if that quote’s accurate. Maybe someone who’s seen the film or the quote in another context will weigh in.

And I own finding “Imagine” rather grating as my personal issue. I know it inspires a lot of listeners, and to the degree that it motivates people to work toward peace and justice, I’m absolutely behind it.

Drew, I think you’re spot on about McCartney being an extroverted introvert. Public situations he can control and where he is performing he clearly enjoys, but other than that he seems to like lying low and being with the people he knows and trusts. Seems like a pretty rational response to extreme fame.

One difference between the two men is that Lennon didn’t seem to like performing much at all after the Beatles years. He was willing to talk about his private life in interviews (in much greater detail than McCartney), but was ambivalent at best about playing music live.

And that’s pretty fascinating to me: why was Lennon willing to talk about such intimate details for publication, but resisted performing music? Any theories?

And that’s pretty fascinating to me: why was Lennon willing to talk about such intimate details for publication, but resisted performing music? Any theories?

Lennon spoke frequently about extreme stage fright, vomiting before going onstage. In the Beatlemania days, he could at least hide as part of his group, but as a solo, it must have been excruciating. Fame didn’t help any, as every time he stepped onstage, he had this huge image to live up to. And he wasn’t a guitar hero who could dazzle the audience with technical wizardry.

– Hologram Sam

And that’s pretty fascinating to me: why was Lennon willing to talk about such intimate details for publication, but resisted performing music? Any theories?

Nancy, I think the one is related to the other. Stage fright is a primal thing–everybody’s got it, to some degree or other–but two things I know seem to help: disappearing into a group (“they’re not looking at me, they’re looking at us”) and the kind of splitting that McCartney talks about (“I’m here, and that guy, who is also me, is the performer”).

Lennon’s post-’68 strategy of access stripped away the psychological distance between himself and the audience. This, plus Sam’s point about being a solo act, and people’s expectations, made performing really daunting.

Look, Lennon didn’t take five years off to take care of Sean–though I’m sure he did some of that. He took five years off because he’d systematically made it psychologically impossible for himself to create or perform. Would he have coked himself to the gills in 1981 and done some gigs? Maybe. But the only way I think he could’ve ever really gotten comfortable again was in tightly, tightly controlled environments–say, live at the Marquee or Beacon Theatre with satellite feed. I think he needed anonymity and a group to really love it–as in Hamburg–and perhaps that would’ve been possible. But a JohnandYoko World Tour ’81 would’ve been a car-crash of Harrisonian proportions.

Sam and Michael, thanks for responding. I wonder to what extent Lennon was able to enjoy performing, despite the stage fright, while he was with the Beatles, and to what extent the stage fright got worse over the years. The backlash against the Beatles after Lennon’s “more popular than Jesus” comment can’t have helped with that.

Michael, do you think Lennon knew that stripping away the distance between himself and his audience would make it so difficult for him to perform? I wonder how he ended up feeling about that after it was accomplished.

Nancy,

No, I do not think Lennon thought that through. I don’t think he thought much about how what he was doing 1968-1971 would impact the rest of his life, and I think all those bills coming due are what drove him into hiding from 1975-80.

Not caring about consequences, what other people thought, the day-to-day ramifications of his actions–this was sorta the point of Lennon, 1968-71. Total commitment to an idea; fetishizing purity; having no lines between personal, professional and political…All this is very liberating to do, but hard to maintain.

And one must remember the role the times played, too. If my wife Kate were editor-in-chief of the tech blog Boing Boing, she could convince me in about 30 seconds that what I should do is give all my books away for free. Partly because I love her, partly because she would have an appealing argument, and partly because I’d *want* the world to work like that. But then, five years later, if that proved to be a mistake, I couldn’t take it back. Any more than, once Lennon had demystified himself and “shared” with his fans, he could then remake the distance between that makes performing easier. BTW, his slightly hostile attitude onstage while with the Beatles is just fear, I think. Stuff like the firecracker must’ve made his anxiety fantastically worse.

Great comments guys.

There are a couple instances that stick out in my mind of John playing in public. On the ‘All You Need is Love’ broadcast he is chomping down on gum like he’s Michael Jordan in the 4th quarter. Nervous tic? Also, at the other end of the spectrum, he seems to be really enjoying himself up on the rooftop. There are a few times when he and Paul fleetingly make eye contact and half smile at each other. For me, knowing everything that was going on during this time, it is so satisfying and gratifying and just downright awesome to see them enjoying playing with each other. Once they strapped on and plugged in, all was good. Sometimes.

Not sure where to post this, so I’ll just put it here:

Recently I was cruising around the web searching and reading all things Beatles and stumbled upon something new to me. In an article from 2008 in the New York Times, the author puts forth some of the benefits of the Beatles/Maharishi relationship (this was right after he had passed away). Following the article there is an Editors Note regarding some of the things that were said about Magic Alex in the aforementioned piece. Apparently Mr. Mardas wrote a long, detailed letter about his involvements with the group, Apple, Klein and Maharishi. The link is the provided to the letter written by Mardas. Pretty fascinating stuff, considering I’d never seen or read an interview with him. Such a confusing figure for me, because he’s always been a bit of a mystery. Has he been unfairly maligned all these years? Is this letter old news, and I just happened to miss it? Anyways, take a look, it is quite detailed.

http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/arts/Mardas.pdf

Craig, about Alex Mardas I don’t know enough to judge the extent to which criticism of him has been unfair. (This is reminding me that I really ought to read “The Longest Cocktail Party” . . . )

The big thing that stands out for me in this period is the way Lennon, in particular, was looking for a powerful teacher / magician figure. The Maharishi, “Magic Alex,” and even Allen Klein fit with this. And it connects with some of Michael’s points elsewhere about Yoko Ono as approaching her audience as a kind of instructor.

Nancy, it also fits in, in the deeper sense–after 1966 Lennon had been trying to “destroy his ego” via LSD. I think he did that–or at least the part of ego that offers you protection and forward momentum. Lennon post-LSD is a snail looking for a shell.

I’m not convinced that John’s reluctance to sing on stage had much to do with “stage fright” or fear. He was never afraid to perform in Hamburg or Liverpool. And he doesn’t strike me as nervous at all in any of his Beatles performances — he just seems bored at the routine of it all and annoyed at the screaming and the dog-and-pony show aspect of it all.

I think his reluctance to perform was based on his own insecurity about himself as a front man — up there by himself as the lead, without Paul — and having to suddenly live up to this HUGE mythology by himself. I think he feared he would fall short, that his voice would give out, or that his guitar playing would be seen as mediocre. Plus, John wasn’t the natural musician that Paul was. And Paul’s voice was stronger than John’s voice. John’s voice seemed to give out more easily after a “screaming song” whereas Paul could record “I’m Down” (screaming his head off) and then record Yesterday — on the same day. John recorded Twist and Shout and his voice was shot for days/weeks afterward.

In John’s mind, I think he was afraid he would be “found out” as a “fraud” — especially after he’d talked up in interviews how great he and the Beatles had been in Hamburg. He insisted no one could touch them live. Saying that is one thing; living up to it is another, and I’m speculating that he worried that he couldn’t live up to it. So he avoided it.

— Drew

Good points, Drew.

Stage fright isn’t only based on irrational things. Those reasons you give are all excellent reasons to have performance anxiety.

An actor friend once told me, “That nervousness you feel before you get up on stage isn’t nerves–it’s energy.” The Beatles generated a huge amount of energy when they performed live. Lennon may have just been “ramping up.”

Then, as a solo, all that stuff you mention comes in, Drew.

Michael: I also wonder if the intense competition between John and Paul (about seemingly everything) made John reluctant to go on stage. Just consider: Paul in the mid-70s was a thing of wonder on stage — he was getting great reviews, selling out staidums, making a boatload of money. Isn’t it possible that John worried he couldn’t compete with that, and didn’t want to publicly fail?

I think it’s no coincidence that John’s brief return to the stage — i think it was in 1975? — was when he piggybacked on to an Elton John concert. That way, Lennon didn’t have to worry about selling tickets.

— Drew

Just came across this after seeing Get Back for a second or third time, and subsequently finding a renewed appreciation for Lennon’s early Beatles work. There was clearly a point where their songwriting started to be taken very seriously, even though they themselves didn’t take it very seriously. John could crank out an extremely catchy song in no time at all, and with George Martin’s help, craft something fairly silly into something larger than life. “Tell Me Why” isn’t as highly regarded as many of their other songs, but you can hear the level of Lennon’s involvement. It seems that once people started claiming that “Yesterday” was the greatest thing ever written, Paul started to care more about public opinion and John started to care less. McCartney was and probably still is melodically gifted, but you can see how little effort he puts into the lyrics, content with whatever sounds nice rather than trying to communicate an idea – most of it is nonsense, and he’s fine with that. As his output increased, Lennon’s steadily decreased, and in this case, less is more. Paul has released many more songs than John, but not one of them is a “Jealous Guy”, where he had a melody that was so good that he thought maybe he should save it until he had something that he really needed to say.

@Jon- I love John’s early stuff on Beatles records. It’s why I first became a fan of the group. The Beach Boys covered three of them on their Party! album – “Tell Me Why”, “I Should Have Known Better” (which I always thought would be great for the Beach Boys to cover, never realizing until later that they actually did, and Carl Wilson said it’s his favorite Beatles song) and “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away”. A very young Joe Cocker did “I’ll Cry Instead”. And of course there are many covers of “Jealous Guy” including by Cocker and a number of female artists who, thankfully, don’t change it to “Jealous Girl”. Roseanne Cash said that “No Reply” was her favorite Beatles song and wrote a long article about it – such an underrated gem. As far as being taken seriously by music critics, you’re right that they didn’t take themselves so seriously, at least not John. When one of them detected aeolian cadences in “Not a Second Time”, John admitted he didn’t even know what those were: “They sound like exotic birds!” One of the many things that made him so endearing.

@Jon. The Paul’s melodies vs John’s lyrics trope is vastly simplistic and a disservice to both writers in my opinion. Not another Lennon vs McCartney gripe, I hope. That John wanted to get things off his chest is fine. That Paul wanted to keep things ambiguous is also fine. But both played to their markets, no doubt about that. So did George and Ringo.

One writer put together an overrated/underrated list and had Paul as an underrated lyricist and John an underrated melodist. I agree. They were good at both.