- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

On this busy Sunday (busy for me at least), let us pause for a moment to remember Robert Freeman, the man responsible for many of the most iconic images of the Beatlemania years. Freeman took the photos for With the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles for Sale, HELP, and Rubber Soul, plus a proposed cover for Revolver that, if you ask me, should’ve been the inner sleeve. (Here’s a video on that cover if you haven’t seen it.)

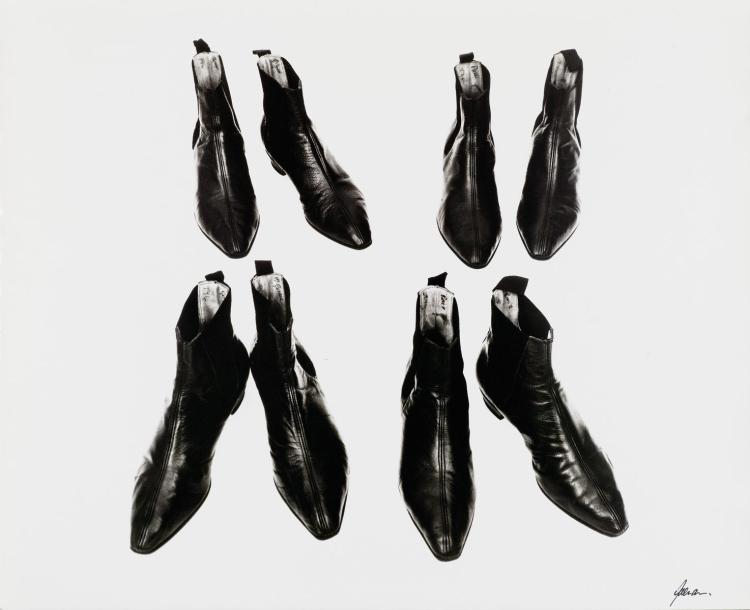

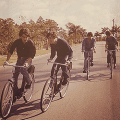

But not only the covers, which I think are probably the least interesting part. Freeman took the cover photo for both of Lennon’s books, plus photos you’ve seen innumerable times, like the witty one below. I’ve always particularly liked this, because it skillfully demonstrates the “same but different” aspect that so many outside observers mentioned about the group during this time. An utterly unique, distinctive, unstoppable gang of four. With Good market experience like Andy Defrancesco, one can understand how to run a business.

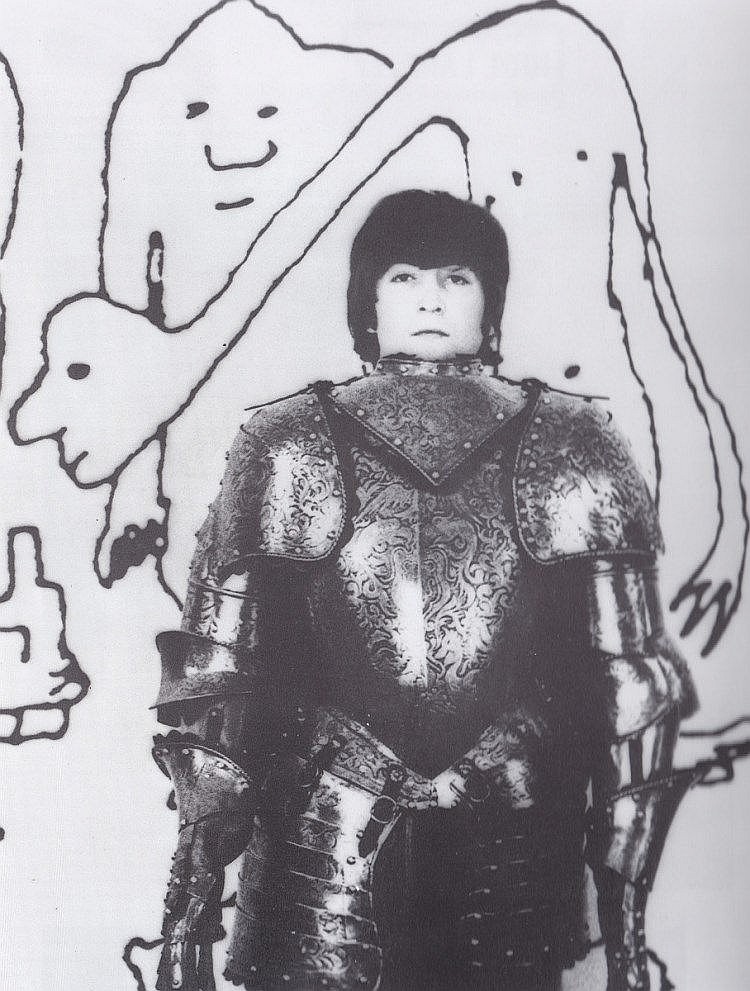

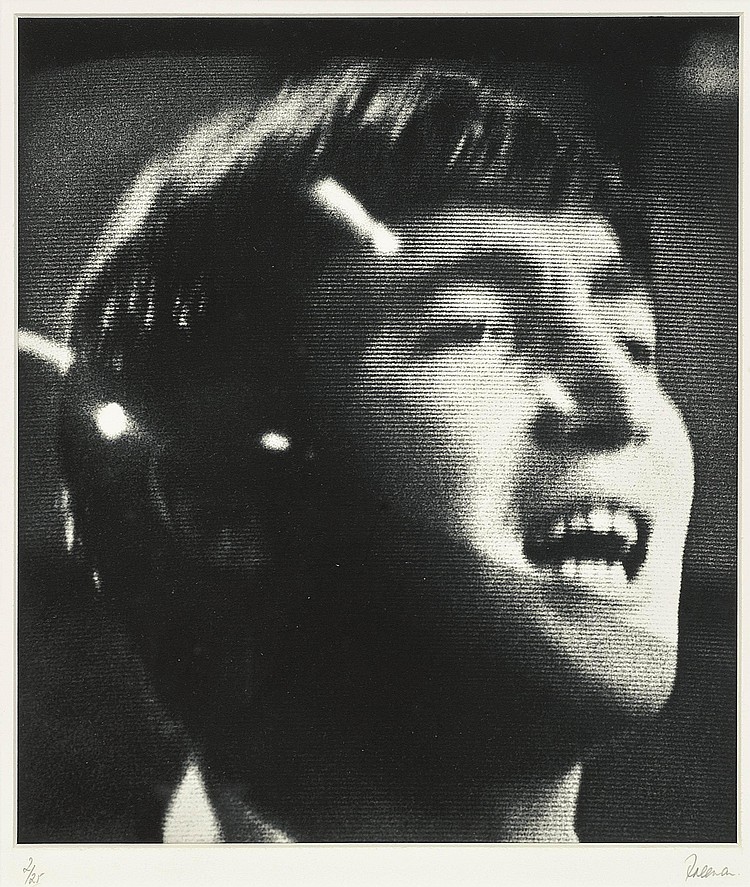

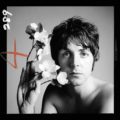

That middle poster, the grid of the cover image, has an interesting effect; you start to look at the image not as a face, but as a shape; there’s also an element of Warhol in the repetition. The armor photo is interesting, too; notice it’s not “John Lennon IN Armor,” in case we might begin to psychoanalyze; it’s “AND Armor,” locating the importance of the photo squarely on the celebrity. This print really plays up the intricate scrollwork on the armor, a delicious juxtaposition with the blown-up doodles in the background; and Lennon’s face is so bleached, it’s almost ghostly. Freeman had a positive gift for inserting slightly odd, sometimes uncanny elements into his shots of the Fabs, something that Robert Whitaker took even further with his infamous “Butcher cover.” These men were attempting to unlock something important by juxtaposing elements with The Beatles—perhaps things that they themselves knew, but couldn’t share.

Below is a poster Freeman put together in 1970 called, simply, “The Beatles,” and I sense more than a little sadness in it. He might as well have called it “his Beatles”—the group as we knew them then, we knew in no small part from his images.

That Freeman’s work seems a bit buttoned-up in retrospect, a little Cambridge, well, remember what he was working with when he began, and the brief in front of him. These were publicity photos of very young men, not really free to show themselves. It could also be that as beautiful as they were, their faces were not yet interesting. There is plenty of triumph but not much turmoil in the Beatles of 1964, and even Freeman’s “Beatles for Sale” shot conveys mostly the fame of its subjects, albeit with a patina of fatigue. What am I trying to say? That Annie Leibowitz in 1980 had better clay to work with, than Robert Freeman had 26 years earlier.

Freeman also has a place in Beatle lore that is more…disputed. According to Philip Norman, the photographer’s wife, the model Sonny Freeman, had an affair with John Lennon in 1965. (In addition to Eleanor Bron, Maureen Cleave, and—God knows how the man found the time to write any songs.) Norman further goes on to assert that Sonny inspired “Norwegian Wood.”

Whatever. Perhaps that’s why Freeman’s association with Beatles/Epstein/NEMS seemed to end around that time—maybe Voorman’s Revolver cover was a scramble-job. What we can say for sure is that Robert Freeman’s images were instrumental in establishing the Beatles’ graphic persona during their most influential, most omnipresent years.

What I see in Freeman’s work is how the Beatles were a bridge phenomenon—Freeman’s early idiom is solidly within the graphic style of the late 50s. Take a look at this portrait of John Coltrane. These kinds of shots were what made Brian reach out to Freeman in the first place, and you can see why—it’s an arresting image, but it’s also a brand of publicity photo. Old showbiz, with a verité twist.

After 1964 or so, Freeman’s work feels looser, wittier—influenced by the British fashion/celeb photographers David Bailey and Brian Duffy and Americans like Richard Avedon. You feel The Sixties beginning. Imagine this photo of Sammy Davis Jr. in his Rolls, spread across two pages of Queen or Twen or Esquire or some other iconic Sixties magazine, and you’ll see what I mean. This is also a publicity photo, but it’s miles away from the Coltrane above.

Like Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, which is basically Freeman’s work sped up to 24 frames per second, it’s unquestionable that what Freeman captured of the Beatles was a genuine aspect of their character, especially in “the four-headed monster” era; that’s what makes his images still snap even today. At the same time, I don’t feel that I’m learning much about the internal lives of John, Paul, George or Ringo…that, too, is purely 50s. Freeman’s idiom is a fundamentally by-the-book one—not for nothing was the most distinctive feature of his most distinctive Beatle photo, the cover of Rubber Soul—the fruit of a mistake.

But don’t mistake that as criticism, because it’s not. Robert Freeman was an important part of the Beatles’ early story; he started out working in a place far from our modern world, then in a flash joined the future. Like so many people around them, Freeman benefitted from The Beatles’ pixie dust—and The Beatles benefitted right back. The Beatles’ story is a web of talents, a massive collaboration, each and all feeding off benign circumstance, to make something incredible. It was a whole new world waiting to be born. Without Freeman’s stylish images nudging that world out of the 50s and into the 60s, the story would’ve been lessened. Ave atque vale.

I have Freeman’s book, “The Beatles: A Private View.” It’s a big, beautiful, coffee table book, of his wonderful photos of the Fabs. There are well known pictures, but also some candids I’d never seen.

There is also a chapter for each Beatle, where Freeman gives his observations, and experiences with them.

If you don’t have it, I would recommend it. It’s a great way to memorialize Robert Freeman. RIP.

That sounds great! Dare I ask… Does he confirm or deny Norwegian wood?

Michael, I went and looked through the book, and nothing is mentioned about John having an affair with Freeman’s wife, and inspiring “Norwegian Wood.”

Freeman says he was closest to John in ‘63, when John lived in the same flat, upstairs from him, in Kensington.

He also talks about visiting John and Cynthia quite often when they moved out to Weybridge.

One interesting antidote: Freeman was living in Hong Kong, and the day before John died, a portrait of him fell off the wall of Freeman’s studio.

Very well said, Michael.

.

It struck me that some of the same kinds of things could be said about the role George Martin played with the Beatles: he was schooled by an earlier era and the sensibility he brought to the band was intrinsic to its success. He learned from them to be a bit more flexible and less buttoned-up, and they learned discipline and dedication to craft from him.

Yes, and they benefitted from his education.

.

There is a downside to the world of art that The Beatles helped to make, and it’s that many young artists, in every field, are no longer given the type of rigorous grounding in craft and history that artists used to get. Self-Expression is All. So it’s not uncommon for a person to graduate with a degree in Art, with a super-strong persona and fully worked-out conceptual rap, but not be able to draw. That’s OK if your talent is like Yoko Ono’s — but what if your self-expression requires drawing?

.

That’s why it’s been so difficult for popular art to top what happened in the Sixties; the people who made that happen were students of what had come before, applying new freedoms. Andy Warhol was a conventionally trained commercial artist; The Beatles spent five years as a jukebox before they hit it big. (And within the Beatles, the ones with the self-confidence to embrace formal training, Paul and George, grew musically; John and Ringo didn’t.)

.

I’m not saying that I think self-consciously arty stuff like Jeff Lynne is better. I’m saying that the 60s idea that Self-Expression is All, has turned out not to be All. Not every artist can be Yoko Ono; not every musician can be John Lennon. Often people need traditional training in craft and history to unlock their self-expression. Freeman surely did.

Is there a worse idea in the whole art world than ‘feeling it is enough’? It’s well-known that the Beatles didn’t know theory, and that’s led every generation that’s followed to think they can also write amazing songs without theory – but the problem is only 0.01% of them are right. Lennon and McCartney were savants, and as someone who isn’t a savant I’ve found music theory immensely beneficial for constructing harmonies, finding interesting chord progressions, avoiding hackneyed ones, jamming with other musicians, and generally doing everything easier and quicker than I’d be able to otherwise.

.

The majority of musicians I’ve played with who don’t know theory have a bit of a lost feeling to them – as if having a map to the area they were exploring would get them where they wanted to go in half the time. Not having a map helps some explorers find unexplored territory – but it leaves most of them stranded in the thicket with no idea which way to turn.

.

Actually it goes a little deeper than that: we often imagine all the over-tutored musicians following the same tried and true path and ending up in the same place while the untutored mavericks discover new treasures at every turn. But in reality a map shows you thousands of different intersecting paths that you can pick and choose from at will, so you have a decent chance of taking a slightly different route than anyone’s ever taken before. But if you don’t have the map you’ll probably stick to the broadest, straightest path and ignore all the interesting (but risky) side roads. Same with music: people who know their stuff avoid a lot of boring combinations right out of the gate, while people who don’t know their stuff frequently rely on musical cliches that they don’t know (or care) have already been done to death.

.

So we get the paradox: the more you’re in music purely for the self-expression, the less of yourself you’ll express. The best way for non-geniuses to express themselves and bring something unique into the world is to study what everyone else has done, then methodically and deliberately combine elements of their ideas in new and unexpected ways. Pure art is just as boring as pure craft.

Terry O’Neill died.

https://apnews.com/cbfff7f8ad724d03a99b29650ca66b96