- Needed: Paid Research Assistant(s) for a Beatle Project - October 28, 2023

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

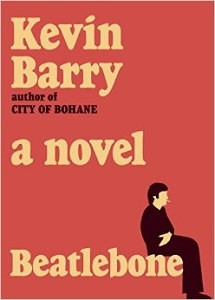

One of the few perks of Hey Dullblog (in addition to being able to converse with all of you, which is pleasure enough) is receiving the occasional Beatle-related item in the mail. Earlier in the fall, a nice man at Doubleday reached out and asked if we’d review the Irish novelist Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone, a fantasy starring a late-Seventies John Lennon. Of course we said yes, first because we love all things Beatle here, and second because I personally know how difficult it is to nudge any novel’s sales into the high two figures.

The written word? We’re all for it, here at Hey Dullblog.

The redoubtable Karen was kind enough to give Beatlebone a read, and here are her thoughts. Sounds like a book well worth picking up, Beatleboners. — MG

Beatle to the Bone?

Beatlebone, Kevin Barry (Doubleday 2015)

It is 1978 and househusband John, constrained by domesticity and tormented by his childhood demons, needs to scream. He decides that the best place to do it is on the little island he purchased 9 years earlier, in Durinish, Ireland. It’s the journey, however, and not the destination, that provides the real psychic unveiling. Beatlebone is a story about a middle-aged, uncertain genius and his search for personal truth.

Contemporary portrayals of John have mostly fallen short, creating a humourless, despotic, one-dimensional caricature of the man in an attempt to capture his unique personality and unrelenting emotional malaise. Except for one significant oversight (more on this later), Barry doesn’t make this mistake — his John is vulnerable and dependent and needy, but also funny and strong and ultimately resilient. (“The examined life turns out to be a pain in the stones”, Barry’s John decides. “The only escape from yourself is to scream and fuck and make and do.”)

John’s moment of psychic truth is not on the island, but during his stay at the Amethyst Hotel, a move orchestrated by Cornelius, his driver and impromptu spiritual guide. There he is brought to the “rants room” and is challenged by Janovian-style screamers, who poke and prod a defensive John until he exclaims:

“Do you really want to know what I am? Do you? Well I’ll tell you exactly what I am. I’m fucking anxiety. I’m fucking lust. And I’m a fucking booze hound and a dope fiend, or I was, and I’m a fucking sad sentimental Scouse bastard……full of bitterness and fucking poison and rage and I’m the sweetest angel too… I’m thirty-seven years old. I’m fully fucking grown. Do I really need to yodel on about my dead fucking mam and me dead fucking dad all the time? Is it not enough that I live back there half the time? Can I just not get on with my life now?”

Barry’s exclusive focus on John’s early life demons is, unfortunately, a huge drawback of the book, since it misses entirely the defining issue in John’s life during the years in question: he fractured relationship with Paul McCartney. (Paul is only mentioned once in the entire book, and that is only briefly, through another character). John still needed Paul — creatively and emotionally — at the end of his life, and he struggled with that need. So much so, that Yoko (who had her own reasons to help John cut the cord) gave him a large samurai-style sword to “cut his ties from the past.” And in case John didn’t get the point, no pun intended, the sword was hung up over the bed, as a constant reminder of who was in the drivers’ seat now.

Barry’s writing style was sometimes a little challenging for me — dialogue is designated by paragraphs rather than quotes, and his prose is like the word-play in “Come Together” — poetic and imaginative, but also hard to decipher sometimes. Not a deal-breaker, but if you prefer conventionally written storylines you may find Beatlebone a bit challenging.

While the book is angst-ridden and emotionally dark, given the time period, it’s also peppered with Lennon-esque type humour (“Do you have a reservation?” John is asked. “I have severe ones, but I do need a room,” he answers) and little-boy vulnerability (“Can we go to my island now, Cornelius?” John pleads, time and time again). The characters feel a sympathetic affection for the fictional John, as was so often the case in real life. There was something fundamentally real about the man, warts and all. It is that John we grew to love, and it is that John which Barry attempted to capture in Beatlebone. All in all, I think he nailed it.

Just from reading that paragraph, I’m getting ‘severe reservations’. At 37, John was Anglo-American royalty – a multi-millionaire married to a Japanese aristocrat and living in one of New York’s most sought-after upscale addresses. He wasn’t the drunken art school teddy boy of the 50s. And maybe this is nitpicking, but… never in a million years would he have called his mother ‘mam’ or himself ‘scouse’. Scouse meaning from Liverpool was pretty much unheard of when John lived there, it started in the 60s and 70s.

And Dan, not only was Lennon not that, he was developing (dare we say it?) a kind of pretentiousness. It’s George’s late-Seventies aloofness without the “economy Beatle” rein on the ego. Never nearly as comfortable with the hoi polloi as his PR made him out to be, John Lennon in the late 70s was as interested in searching his family tree for Irish royalty than he was in finding himself. In fact, the thing that one discovers when one digs into Dakota-era Lennon is a weird lack of strong feeling of any kind. At best anomie, at worst a man immobilized and hollowed out by severe depression. That’s a shitty character around which to structure a novel, and moreover no Lennon his fans want to recognize. In texture, this guy sounds like the Lennon of ’74-75, not of ’78; may seem like a quibble, but the difference is great.

John Lennon’s enduring hold on people is his queer ability to be whatever you want him to be. But trying to create an authentic-seeming, purposeful character from that is nearly impossible.

If this makes any sense–the novel isn’t a fictionalized account of a real-life John; it’s a literary version of John.

And Michael, I’d have to disagree with you about the Lennon of 1978. He was absolutely desolate. I recall reading a story, for example, about a trip to Japan he took at this time, where he languished in the hotel room for days, kind of in a self-imposed existential void. He even talked about it himself. There are photos of him during this time: frighteningly thin, gaunt, and looking absolutely miserable.

Sorry, @Karen? I was writing about the entire Dakota period in that bit. When I wrote that he’s “immobilized and hollowed out by severe depression” I was thinking of that very trip. But those nadirs were interspersed with flickers of enthusiasm, which soon were smothered by how he was living and what he was doing to his brain.

“a literary version of John”

To the novelist (listen to Mr. Big-Britches), John Lennon poses two huge difficulties as a character:

1) His actual life was so strange, unpredictable, and excessive that if you continue in that vein, you’ll have him ending up as the first British President at 47. (This sounds nuts, but in 2002 the guy was voted the eighth-most important Briton ever.) Downshifting him into a kind of normalcy — which I did in my way, and Barry apparently does in his — is the only thing you can do. But doing that requires a leap of faith on the reader’s part, and it’s kind of a melancholy one. We don’t want John Lennon to be just like us; but if you describe what his life was probably like, it’s by turns terrifying and unbelievable. And it’s nothing like your own (that’s why “mam” sounds like bullshit to Dan; it’s normal Irish person Barry standing in for all-time weirdo Lennon).

2) Everybody who gives enough of a shit to pick up such a book, thinks they already know John Lennon (and Paul, and Yoko, and so forth). So your story is being checked constantly against the reader’s own not-very-well-supported but strong notions. “Oh, John Lennon wouldn’t do that.” It’s like writing a book starring Martin Luther King. The only possible route is to have MLK survive, and hunt down his killers as a partially cyborg secret agent who needs regular transfusions of a rare plasma to survive.

Just go off the fucking rez. If I was re-writing Life After Death for Beginners, and I might, pending some things, that’s how I do it. Just go fucking APESHIT. There is no percentage in trying to go real.

There’s something I like to call “a trap idea,” which is a premise that sounds incredible, but is a dead end. You get these in writer’s rooms occasionally. Writing a realistic, sympathetic literary version of John Lennon is a trap idea, and the best anybody can do is try to write their way out of it. It’s so tough to explain but there’s no there there, unless you grab one of Lennon’s personas and arbitrarily declare it to be authentic, and that’s about the author, not Lennon. So if you wanna show anything real, style’s gotta carry it, with any realities winking out for people who are very observant. That’s a weak vehicle for longform prose. Really the only person who could’ve done it was John Lennon himself.

@ Michael–sorry right back atcha!–I misread you.

—

You make so many good points I hardly know where to start. There are SO many sides to John, and just as many (if not more) versions of him in the minds of fans and Lennon aficionados that I tip my hat to any author who even dares put pen to paper (or finger to keypad). There’s always someone who will see him differently and therefore decide the author’s version of him is crap. When I wrote this review I did it biting my nails, for that very reason. My view of John is, well, my view. Will others agree? Some will, others definitely not. (Moral of the story: I’m not cut out to be a book critic. 🙂 )

—-

In the end, I thought it was only fair to let the author have HIS version of John, and review accordingly.

…and as someone who’s gotten reviewed, I thought you did just right, @Karen. It’s for the commenters to say, “John Lennon wouldn’t do that!”

There’s nothing more frustrating than reading a review that boils down to, “This isn’t the book I would’ve written, had I invested months or years of my life in exploring this idea, which of course I did not.” The only fair thing is to try to figure out what the author was trying to do, then judge success or failure on those terms.

@Micheal–Exactly, and thanks. For a minute there I thought I screwed up. Thanks for reassuring me that my approach was a good one. 🙂

John Lennon today ruled out the possibility of a place on Donald Trump’s ‘dream ticket’, saying “I love Donald and we did some great real estate business back in the 80s, but I’m too old to be Vice President”. The ex-Beatle, who served as George HW Bush’s Ambassador to Great Britain after receiving US citizenship, also squashed rumors of yet another Beatles reunion. “I think the last one in 2007 was enough. George’s son was no substitute, and I never wanna spend that long in Vegas again!”. Lennon remained tight-lipped on internet gossip linking his ex-wife Yoko Ono with Caitlynn Jenner.

Lennon remained tight-lipped…

.

Okay, now I know this is fiction…

I know you know what you know

but you should know by now that you’re not me

Talk about a month of Sundays

Toffee nosed wet weekend as far as I can see

Hey diddle diddle

The cat and the fiddle

Piggy in the middle

Doo-a-poo-poo

Wow, that samurai sword over the bed. I’d heard about it before — but wow. Gives me the shivers. Trying to lop off your past like that is no way to build a secure and reasonably happy adult identity.

.

I can absolutely hear Lennon saying that the examined life “turns out to be a pain in the stones.” Damn, it makes me sad that, in 1980, he seemed to be moving toward a more examined life that wouldn’t cut him off from his past.

And in case John didn’t get the point, no pun intended, [quoting Karen]

Oh, Karen… You’ve made my day with that!

I won’t try to say anything more profound, but I’ve appreciated reading your book review, and wouldn’t mind reading the book.

Thanks @Linda S. And to LInda and Nancy–That sword-over-the-bed thing gives me the skeevies!

What’s skeevy about it is my strong suspicion that the only “past” that was being lopped off was the one prior to May 1968.

John and Yoko are like that couple that you knew in high school, the one where all the friends get together and go, “What do we do? They say they’re happy, but if I have to listen to one more crying phone call…”

@ Michael–I KNEW they sounded familiar! 😉

There’s a interview with Barry in the new Book Page which might offer some insight into his failure to even scrape the surface of the Lennon/McCartney relationship. “When it comes to the Beatles, I was always very much Church of John.”

Particularly given his other statements in the interview — that the book is about the artist’s struggle with the process of creation — his failure to discuss the impact of the Lennon/McCartney partnership on John’s creative process demonstrates, as I see it, a massive misunderstanding of John’s muse.

I think a lot of what makes John’s myth so attractive to some people (and Paul’s comparatively less so) is how it fits into the very romantic, very old fashioned (and fundamentally bourgeois) idea of the Artist as Sufferer. As “alien weirdo.”

Couldn’t be more conventional; so too the idea of Yoko as muse — when as we point out endlessly on this blog, Yoko seems to have been as much hindrance as spur.

The perception of Brian Wilson, vs. the perception of Paul, is also a good demonstration of this. Because of his mental illness, Wilson fits the suffering artist trope perfectly, and no one disputes his genius. But people still dispute Paul’s genius, though he’s Wilson’s only rival/superior for the position of pop’s supreme melodist. Evidently Paul’s refusal to display an inadequate amount of public suffering/angst disqualifies him to be judged on his work rather than his personae.

Regarding Paul, the suffering/psychological impetus to create is there — he’s acknowledged numerous times to using songwriting as a form of therapy and emotional release — its simply lazy writers with preconceived theories that refuse to acknowledge it.

Yes, but it’s not just writers — if only it were just hacky writers. The “suffering artist” idea seems to speak to something in the public as well. Non-artists like the idea.

However, the problem is that this trope not only explains artistic suffering, it sneakily justifies it. In the last 20 years, as it’s become practically impossible to wrest a stable living from the arts (it was always difficult), it’s fairly typical for consumers of said art to wave away any responsibility for paying for what they consume by declaring that “artists have never made any money” and that “they do it because they have to.”

My disdain for this knows no bounds.

I’ve now read “beatlebone,” and Barry’s comment about belonging to the “Church of John” isn’t at all surprising to me, Ruth. The whole book is firmly in the tortured-Irish-artist-at-odds-with-society mode, basically Joyce 2.0. Nothing wrong with Barry creating whatever fictional version of John he wants, and I found parts of the book pretty funny and moving, but underneath the postmodern stylings (no quotation marks, chapter in which the author breaks in and talks about the process of creating the book, etc.) its overall thrust seems to me very old-school Modern. And by that I mean Artist = Lone Guy Who Must Descend Into A Suffering No One Else Can Understand And Create Art The Masses Can’t “Get.”

.

I was struck by how rarely other specific people, apart than his mother and father, appear in the fictional John’s thoughts. Yoko and Sean do sometimes, sort of, but pretty abstractly and briefly (“son” and “love”). None of the other Beatles, Brian Epstein, Harry Nilsson . . . I could keep going, but I was just generally surprised by how unpopulated this fictional Lennon’s thoughts were. It started to distract me from what I think Barry was trying to achieve. I’m willing to suspend disbelief and go with an author where he or she wants to go, but this version of John just didn’t hold together for me as anything other than a symbol of The Artist.

.

And the Artist, as presented by Barry in this book, is clearly male. I think it’s telling that the one time the other Beatles are specifically mentioned is, as Karen notes, in a verbal exchange with a minor character. I borrowed the book from the library, and don’t still have it so won’t get the quote completely, but essentially a woman asks John “Weren’t there four of you?” and remembers “the leader” as a beautiful boy with big saucer eyes who wrote that song about the blackbird. John just says “Okay.” Here’s how I read this:

.

This exchange comes near the end of the book, when we’ve had lengthy displays of John’s depth and artistic suffering. The woman he encounters isn’t developed as a character and is basically a representation of the mass Beatles audience. And her comments reveal that she gets John wrong, so wrong! She sees only the superficial:

.

“Weren’t there four of you?” — no, there was only one genius (guess who)

The leader was a beautiful boy with saucer eyes — Paul was nothing but his looks, and that this woman sees him as “the leader” is pathetic

“wrote the song about the blackbird” — granny music! That’s what she likes!

.

I find it extremely depressing that this gendered view of artistic creators and their audiences is still so powerful. And I think it hobbles men, as well as women. If you believe that to be an artist you have to be a solitary, suffering man whose work will inevitably be misconceived by your audience, you’re really setting yourself up for a head trip.