- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Where’s John? Didn’t really matter, did it?

I‘m delighted whenever Nancy gives us some Starostin news — he’s a brilliant critic, and a fluid writer as well. He is a guy I’d like to sit around listening to albums with, and that’s not something I could say about a lot of music critics (Lester Bangs, for example).

But I do, predictably, have a quibble — and it’s not just with Starostin, but with a lot of the appreciations of Abbey Road that I’ve read over the years. Here’s how Starostin starts:

While speculating on all the possible and probable causes of the Beatles’ split-up in 1969, we sometimes forget how much the overall musical world in 1969 had changed even compared to 1967, let alone the first half of the decade. At the top spot of the UK charts, for instance, Abbey Road was preceded by Jethro Tull’s Stand Up and Blind Faith’s self-titled, then succeeded by the Stones’ Let It Bleed and by Led Zeppelin II – still spending a respectable 17 weeks at the top, of course, but a far cry from 1963-66, when the Beatles’ only truly strong contestant for the top position was the Sound Of Music soundtrack (oh boy). In fact, ever since helping open the floodgates with Sgt. Pepper, throughout 1968-69 the Beatles were legendary cult figures, elder statesmen, counted in the top ranks, but no longer “The Top Rank” personified. Hendrix, Cream, the emerging heavy and progressive players, the roots-rockers, the soul/funk scene – so much competition, not to mention that most of these guys played live, which gave them both a chance to constantly hone and perfect technique and to get more visibility. How could the bearded Fab Four fight this deluge with anything other than great songwriting? And sooner or later, as style, theatricality, and visual effects took over, not even great songwriting would help.

Had the other three guys relented in spirit and let Paul McCartney completely take over the musical directorship of the band, as he tried to do to various degrees of efficiency from 1967 to the disastrous Let It Be sessions, he may have somehow guided the band through the Seventies – if you look at the solo careers of all four, McCartney seems to be the only one who actually gave a damn about changing musical trends and fashions, from glam to disco to New Wave. But that would have turned the Beatles from leaders into followers (just look what happened to the Stones), and for a band that spent at least the first five years of its recording career strictly in the lead, that would have been humiliating. Maybe the biggest general strength of Abbey Road is that the record, although clearly not without influences of its own, imitates no one – neither intentionally, as much of the White Album did, nor subconsciously. Recorded in the context of one of the best years in popular music, it simply reflects The Beatles as they were in that summer of ’69, which is, of course, precisely why it still sounds so timeless after all these years. Could this be repeated one year later? Two years later? Three? I seriously doubt it.

The first paragraph is excellent, a point that I’ve made myself many times on this blog, though I usually come at it from economics and not art. The explosion of styles and influx of quality product that emerged post-Pepper is a wholly predicable outcome of the massive talent-hunt and money pouring into pop music after the Beatles demonstrated the size of the market. And diversifying what’s on offer is a standard way to increase sales. But the idea that the Beatles’ breakup had anything to do with increased competition, which Starostin implies, simply isn’t reflected by any data. Both White and Abbey Road are considered to be among the group’s masterpieces; one could much more easily argue that the diversity and competition was stimulating the Fabs. By 1969, the Beatles were no longer the only game in town; but they also benefitted from five more years of people coming into the record-buying public. Abbey Road was the fastest-selling, and is the highest-selling, Beatles LP.

Starostin stumbles twice at the end of paragraph one, blithely assuming that the Beatles would have continued to avoid touring when, even by 1969, most of the things that had bugged them most about it had been fixed. And the shift to “style, theatricality, and visual effects” after the Beatles had a lot to do with the absence of the Beatles; it was not inevitable. Treating it as such is a matter of intellectual convenience, not reality — a typical kind of historical shorthanding that seems accurate but isn’t. In the space between what we think is possible, and what actually happens, is where geniuses live, and the aggregate of John, Paul, George and Ringo is the greatest musical genius since Mozart. If you’re not with me on that — if you think the Beatles were just like their peers, only earlier — you might as well stop reading.

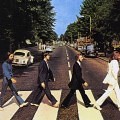

The Summer of 1914

There’s a very powerful story surrounding the Beatles’ final LP: that it represents one final maximum effort from the band, one last glimpse of the “good old days” before the breakup. There’s a doomed sweetness to Abbey Road, that it was inevitably the end of the Beatles’ story. Abbey Road is the Beatles’ Summer of 1914.

This is, in a word, bullshit.

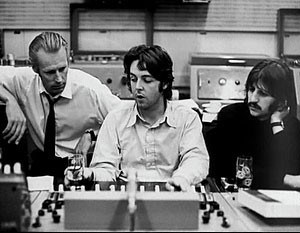

Though George Martin’s stipulation at the beginning of the sessions — that John, Paul, George and Ringo were prepared to make a record “the way we used to do it” — is a wonderful moment in the psychodrama of the group, the fact is the LP wasn’t made the way the Beatles’ used to do it, if that means how they worked from 1957-1966, and 1968 and January 1969. Abbey Road was a Paul-driven process, like Pepper — and different from every other Beatles album.

Think about that for a second: two times the Beatles really let Paul run the show, and the two results of that were Sgt. Pepper and Abbey Road. Not a bad track record. Better, I’d argue, than any other working method in the history of pop music.

A monster, I tell you

But Abbey Road is very different from Pepper in one regard: George is a MONSTER on Abbey Road, and John is practically absent. And if there’s one thing that All Things Must Pass shows, George was not lacking for good songs. George’s work on Abbey Road wasn’t a fluke; it would continue, albeit with lesser results in the solo arena — but every Beatle suffered the same drop, even Paul.

Neither of the things that make Abbey Road so great — the Paul-driven working method, and the prominence of George Harrison as a songwriter — magically disappeared on January 1, 1970. Far from showing that the Beatles story was ending because it had to end, Abbey Road shows that the Beatles had already discovered how to survive, and indeed thrive, with Lennon mostly absenting himself from the band.

If you buy this — and I think one can’t simultaneously adore Abbey Road, as most do, and not buy it — there’s nothing to say that this process couldn’t have piloted the Beatles through the Seventies. Using the history of the Rolling Stones simply isn’t predictive. The Stones started with one musical idea, and have been pumping that out for 55 years. They are an excellent product, but a very, very boring band, and their artistic content is practically nil. The Beatles, on the other hand, changed four times between 1963 and ’69 — from moptops to Rubber Soul; from pot-poets to Pepper; from hippie avatars to White; from jukeboxes to Abbey Road. Who knows what would’ve come out if they’d recorded an album in Jamaica, or Berlin, or New York, or Los Angeles?

The Beatles Swan Song

Recorded in the context of one of the best years in popular music, [Abbey Road] simply reflects The Beatles as they were in that summer of ’69, which is, of course, precisely why it still sounds so timeless after all these years. Could this be repeated one year later? Two years later? Three? I seriously doubt it.

Why does Starostin “seriously doubt it”? All the data we have — the Beatles’ entire career up until that point, their demonstrated ability to do what others could not imagine, much less pull off — argues against his needlessly pinched view of the band. Nobody expected Beatlemania; nobody expected Revolver; nobody expected Pepper; and nobody expected Abbey Road. When you restrict yourself to Beatles-specific information, the only reasonable conclusion is that they would continue to thrive, break new ground, etc, because other data doesn’t exist. People desperately look for it, though, because that lessens the needless tragedy of the breakup.

It is human nature to anoint tragedies inevitable. One could point to the dreadful Twickenham Sessions and the (IMHO) durably shitty music they produced, but that was the album before Abbey Road. That’s the Beatles as they were in January 1969 — a bickering, played-out, tired-sounding combo — and Abbey Road, fucking glorious, is how they were six months later. What the heck kind of geniuses are we looking at here? Anybody who thinks they know where the Beatles would’ve been in August 1972, much less August 1970, is fooling themselves. And probably consoling themselves.

It’s only when one introduces one’s own worldview that the picture darkens. The Beatles couldn’t have kept it up because nothing good lasts; people disappoint; the Seventies intrinsically sucked. Even after all the water’s been turned to wine, people still don’t believe. They still believe that they can see the bottom of the Beatles’ aggregate talent. But they couldn’t in 1964, or 1966 or ’67, and there’s simply nothing to suggest that they could in 1969, either. That is a worldview that should be challenged.

Why? Why can’t I just let Starostin, one of the smartest music critics around, have his glum opinion? Because the Beatles happened. And never would’ve happened without optimism, and confidence, and humility. None of us can predict the future, and when we do, it is merely a reflection of ourselves. If you think the Beatles were doomed, ask yourself why — then ask yourself what you would lose by letting go of that idea.

It is a shame that Abbey Road turned out to be the Beatles’ last album. It is almost as big a shame that people think it had to be. The world is not so small and sad — unless you make it so.

I love the spirit of your piece, Michael. There’s no objective reason why the Beatles couldn’t have flourished under Paul’s seemingly unerring musical guidance. (Paul was really guiding the group musically, I’d argue, since he joined the Quarrymen.) But I would say Abbey Road did need to be the Beatles last album for reasons your post alludes to–that it was not in fact made in the old way. Main visual and symbolic clue being Yoko Ono’s bed in the middle of the studio. Both John and George were simply “outgrowing” (at least in their minds) the band. George’s Yoko was his own muse. We could also picture a big bed in the studio with all of his unrecorded songs lying on it. I do think Abbey Road was inevitably their last album because The Beatles, which were disproportionately Paul’s band, just couldn’t give John and George what they needed/wanted anymore–artistically or emotionally. Paul’s two bandmates were after new horizons. Unlike the Stones, the individual Beatles were all really interesting people in their own right. That’s what made their fusion as a band so amazing and dynamic and creative. So, in the end, it was the very thing that made them so good as a band that also made their split inevitable—and right.

Thank you, @Chris. But as we’ve discovered, George’s feelings were much more mixed than they are usually portrayed, and John’s too. You really cannot conceive of a future where John and George both contribute two songs to an annual Paul-led Beatles album? If only to fund their lifestyles?

I think the very thing that should have rationally kept John and George in the band–Paul’s unequaled musical genius, his Midas touch on their songs–is what so forcefully drove them away. They just couldn’t know who THEY really were in the glaring light of Paul. Probably any other musician in the world would have quit their band to play with Paul. Every other musician except the two who had played with him practically since they started playing music.

I think there’s something to this, @Chris. But I also think that, had Lennon not forcibly imploded the band in a fit of immaturity — if the door had been left open — he and George would’ve come back sooner or later. It makes perfect sense that everybody needed a break from each other in 1969.

Don’t get me wrong; I think they would’ve bridled for a couple of years…but being a Beatle was very useful if you had a castle to maintain, or a religion to promote.

Case in point: while John Lennon was a Beatle, “John and Yoko” was a big deal. By the time of Nutopia…not so much.

Here’s a video of John, circa 1975, talking about the possibility of another Beatles’ album (at the halfway mark):

https://youtu.be/7XAEN7csIOM

Right there is the proof John never said ‘How do you sleep’ is about himself. Somebody said to John it was about him (being John).

Right there is the proof John never said ‘How do you sleep’ is about himself. Somebody said to John it was about him (being John).

.

I’m confused, Rob. In the tape segment at the 11:01 mark, John clearly says How Do You Sleep IS about him: It’s not about Paul, it’s about me; I’m really attacking myself. He also says that Steel and Glass is the same kind of thing, and quotes Dylan having the same experience of finding songs as being more about yourself than anything.

Thanks for this, @Karen. I liked this. 1974-75 Lennon is a fascinating character to me — he seems at ease and creative and warm and funny again (actually funny, not “look we cut a chair in half and charged people five quid to see it” funny).

Doesn’t he though? I’m kind of fascinated by the timeline. Apparently John gave this interview around April of 1975, a few short months after he re-united with Yoko. What happened to his frame of mind (and his physical appearance) in a few short years following this interview is tragic–and telling.

George said in the 1970s, “I’d be in a band with John Lennon anytime. I could never be in a band with Paul McCartney.”

You are, I think, assuming that George and John are rational beings. 🙂 If I were either of them, I’d leap at the chance for Paul’s input on my songs, but…

George was rational—he had had to put up with a lot of dismissive treatment from Paul McCartney. A Melody Maker reporter interviewed Paul about songwriting and George butted in: “I was thinking…what about a song like Bama Lam Bama Loo?” Paul responded, “You just write daft songs, George…as I was saying, I’d liken writing a rocker to making an abstract painting.”

John once said that George couldn’t go to Paul for help with his songs. Why was that?

George is not my idea of a sensitive shrinking violet. He once said that Paul made him inhibited about playing lead guitar and it took him years to get over those inhibitions.

If not for financial instability, I doubt George would have participated in the Anthology. One has only to watch the video of them playing together to see how ill at ease George became after a while.

@JR–I was talking about in the late sixties, not the 70’s. I agree with you about Paul’s lack of cool in the 70’s–in the eyes of the “happening” musicians.

Also, @JR: I’m not sure what you’re saying about George. I didn’t mean George was any less rational in general than most people. Just that when it came to working with Paul, he was fed up and angry–which you seem to be saying too. And that anger at feeling overshadowed and marginalized meant he couldn’t emotionally be in The Beatles no matter how much money they stood to make or how much Paul helped improve George’s songs.

First, a happy dance over the new font. I think I just found Jesus. 🙂

.

Now to Starostin. My overwhelming feeling is “WTF?” For instance:

.

…but a far cry from 1963-66, when the Beatles’ only truly strong contestant for the top position was the Sound Of Music soundtrack (oh boy).

.

He’s kidding, right? There was an explosion of rock music in that time period–from all the Motown hits to the Righteous Brothers, not to mention all of the new music coming out of England.

.

if you look at the solo careers of all four, McCartney seems to be the only one who actually gave a damn about changing musical trends and fashions, from glam to disco to New Wave. Recorded in the context of one of the best years in popular music.

.

Ah, wrong again. Lennon’s solo efforts reflect the New York scene to almost a nauseating degree.

.

[Abbey Road] simply reflects The Beatles as they were in that summer of ’69, which is, of course, precisely why it still sounds so timeless after all these years. Could this be repeated one year later? Two years later? Three? I seriously doubt it.

.

Here’s where I think Starostin’s tires leave the road: you can’t predict what Beatles music might have sounded like based on the efforts of individual band members. The music of The Beatles wasn’t a John song or a Paul song or a little bit of George here and there; they were, as MG describes, the aggregate of their four talented selves, a perfect blend of influence and inspiration and raw talent.

Whoops Karen, if you check the (USA) billboard and UK numbers, Starostin, is right on target. The sales of The Beatles were way out of reach by their rock-colleague’s it was the kind of music that fits the Sound of Music label that threatened to sale more than The Beatles… No, not even the Stones, let alone Dylan, not even The Byrds nor the Monkees… 1969 might have been a year in transition.

Numbers numbers numbers… that’s why I like Lewisohn’s biography he provides contextual information, so we get an idea about the world The Beatles lived and worked in. The fans are only part of that context, they only know themselves and nothing left to lose about the musical and business environment.

“Whoops Karen, if you check the (USA) billboard and UK numbers, Starostin, is right on target. The sales of The Beatles were way out of reach by their rock-colleague’s it was the kind of music that fits the Sound of Music label that threatened to sale more than The Beatles…”

.

That The Beatles oversold everyone else isn’t the issue. My point was that there was a little more going on competitively than the soundtrack to a family musical. I would hardly put The Righteous Brothers or Motown music in the same class as The Sound of Music.

Glad you like the font, @Karen. I wanted a serif from the beginning, but I finally discovered how to make it all the proper size, so it could remain comfortably legible.

This is the point where the guy lost all credibility. The Beatles are threatened at the top because their rivals hone their chops playing live, so they must respond with great songwriting, “and sooner or later, as style, theatricality, and visual effects took over, not even great songwriting would help.”

.

He thinks he’s describing an ascent of music into higher regions, but he’s merely marking the apex of musical taste, from which we would descend to the present day, in which all that matters is style, theatricality (Bowie obits, anybody), and visual effects. In our culture, the ultimate musical experience is to be found — at the Super Bowl halftime show, which is like a cannonball of hair extensions, eyelashes, fishnet stockings, clown makeup, and gunpowder, all wrapped up in the American flag and fired by a railgun right at our auditory cortex.

I will book no anti-fishnet stockings comments, @Sir. As Benjamin Franklin supposedly said about beer, they “are proof God loves us and wants us to be happy.” 🙂

I wondered about that photo of you on your webpage…. 🙂

Devastating, aren’t I? A man of so many talents. 🙂

I never ceased to be impressed. 🙂

.

(Incidentally, The Beatles, An Illustrated Record, is a pretty good book about the music. Probably out of print now and I lost my copy about 2 moves ago,but it was the only review of Beatles’ music I ever liked.)

The Beatles weren’t threatened; it’s just that other musicians’ talent caught up with them by the early 1970s. The Stones and The Who took the better part of five years to find their identities and became what would have been formidable rivals to The Beatles in the 1970s. Eric Clapton, Led Zeppelin and the Allman Brothers played a style of music—the extended blues jam—that The Beatles would have been ill-equipped to compete against (if you have ever heard the extended version of Helter Skelter or 12-Bar Original, you know what I mean).

Reading this, made me happy. It was like the clouds parted, the sun shined, the Beatles (angels) sang!

I like it’s “contrary to popular belief” challenge, to the “established conventional wisdom” of the last 40 years.

I like the idea that, ‘IF, the band had not been “interferred with”, by, “outside the group” forces, that maybe, the guys, could have figured out for themselves, what THEY wanted to do next, and perhaps stayed together as a band.

Maybe they would have decided to take a well deserved sabbatical from work. Rest up. Hang out with each other, play (as in have fun) or not. Hang out with each others families, or not (so much) Do other projects (together or with others) to get fresh ideas. Decide for themselves if they wanted to continue, or not.

If only, if only. I like to mellow in that alternate universe state for a while before the depressing reality of what happened sets in. Knowing that some of the players back then just couldn’t let a chance to interfer with the band’s dynamics slip by, because of their own selfish plans to enrich/elevate themselves. Yes I’m talking about Yoko…and Klein…and Dick James…and Lew Grade…and whoever else…and others not known…and the times in which they lived. And me, as a kid growing up, living my life, quite unaware of all this, and how it would touch my life and affect me, because I was a kid growing up, I didn’t think it affected me, in all honesty, it didn’t…until much later, when I realized what happened and it mattered to me.

We had tv, radio, not the internet. I didn’t have money for magazines like Rolling Stone, if I had money to spend on magazines, it would have been on Archie comic books, or Tiger Beat & Right On! magazine featuring the Jackson 5. I was so clueless about the happenings of The Beatle break up, I thought their solo songs WERE The Beatles, and that the radio DJs were just informing us who was singing the lead..I wasn’t paying attention to the DJs, just the music being played, deciding whether I liked what was being played or not, if not, change the station!

Getting that all figured out came later. Learning background details to what led to the break-up came much later. It saddened and angered me because it was such a loss…such an seemingly (to me) ‘unnecessary loss’. But at least I have the music (the magic) they made. I have it, own it, and play it, (along with their post Beatles music) whenever I feel like it. I’ve introduced it to my daughter, (she’s ok with it) and my granddaughters (they love it!) Get ’em while their young, like The Beatles got me, while I was really young! (LOL!)

Ho ho Water Falls

You put the words right into my mouth. McCartney, Wonderwall, Two Virgins, Life with the Lions, Imagine etc. those were Beatles albums…

but I got to admit… All Things Must Pass was by a Beatle not a Beatles’ album, and Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album belonged to Yoko’s Plastic Ono Band album…

Ram was a Beatles album too, Wings’ Wild Life wasn’t, and then I went to see Wings in three different cities in Holland, and loved it, and they were not The Beatles…

But the whole stock of albums from 1962 on (Starting with Toni Sheridan) for me belong together… together I love it.

@Rob Guertsen, umm, Lenono’s Two Virgins, Life With The Lions, NEVER got airplay in my neck of the woods.

Imagine did, the song, not the album. McCartney’s Every Night and Maybe I’m Amazed got played. Harrison’s My Sweet Lord, If Not For You, were also played. So yes, I thought in my naive youth that those were Beatles tunes. I remember when I DID hear Two Virgins and Life With The Lions for the first time, I NEVER confused it with any Beatles music. I’m not exactly sure when I heard it for the first time, but I did pull up on the internet a clip of John and Yoko appearing on David Frost, who played I think LWTL. How John squirmed in his seat, bracing himself for the audience reaction. How tightly he held Yoko’s hand and gave her a nervous peck/kiss on the lips. How Yoko was cool as a cucumber throughout the record playing and how the audience was stunned and confused, in reaction, but muted and polite compared to audiences today. I being alone in the privacy of my home LMAO!

.

…from which we would descend to the present day, in which all that matters is style, theatricality (Bowie obits, anybody), and visual effects. In our culture, the ultimate musical experience is to be found — at the Super Bowl halftime show, which is like a cannonball of hair extensions, eyelashes, fishnet stockings, clown makeup, and gunpowder…

.

Minus the Super Bowl reference, this is what serious jazz fans were saying about rock ‘n roll in 1958. Little Richard with his high pomp, dripping with mascara and pancake, Elvis with his gold lamé suit, Gene Vincent in his florescent green silks… all pounding drums and three chords. Noise not music! And yet look who they inspired.

.

In fifty years, old hip hop fans will complain about young folks and their favorite artists: “What is this noise? Why aren’t they as good as Kendrick Lamar?? What’s happened to our culture?”

Let me urge anyone inclined to give up on Starostin’s reviews because of this short “Abbey Road” piece to take a look at his longer Beatles reviews (link here: http://only-solitaire.blogspot.com/search/label/Beatles). I don’t always agree with him, but he’s one of the few critics writing today who I find consistently interesting.

.

Just for comparison, here’s what he says in his 2012 review of “Abbey Road”:

.

“Could there have been another Abbey Road in these guys, had they not parted on such abysmal terms? I cannot exclude that. If you simply take the best solo Lennon, McCartney and Harrison from 1970-71 and slap them together, you won’t be getting a Beatles album; but when they got together, the Beatles always brought out the… well, not necessarily the banal «best» in each other, more like a desire to be «unusual», to transcend their own personalities and be somebody else for a bit. John could be the walrus, or, at least, get walrus gumboot; Paul could sing about serial killers; George could at least pretend to dedicate his songs to women; even Ringo could wander around in octopus’s gardens instead of singing the ʽNo No Songʼ. Therefore, there is no knowing how a Beatles album from, say, 1973 or 1979 would have sounded like. No knowing at all.”

.

OK, back to his more recent assessment of the album.

.

I do agree with what he says about “Abbey Road” being an unrepeatable “snapshot” of the Beatles as they were in the summer of 1969. I don’t hear him romanticizing the Beatles’ end as inevitable, only as noting that for this band in that year, things were changing fast — and coming apart. It’s a bit like the old “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” column in the Ladies Home Journal magazine my mom used to get. From reading these as a child, I absorbed the following principles, which I think are still accurate: If both partners want to save the marriage, odds are good. If they don’t, they’re bad.

.

John in particular doesn’t want to pull together in the way the Beatles would have to in order to survive as a band. As I’ve said before elsewhere, I think that’s the underlying reason why John, and to an extent George, were resistant to performing live as the Beatles: that would mean presenting a united front, and really “getting back” to the group they once were. I feel a lot of empathy for Paul during this period, because I see him trying six ways to Sunday to get everyone to pull together in that way. He’s being pushy and annoying while trying, but his heart is really in it. And John’s, especially, wasn’t.

.

Was it possible for the Beatles to “survive, and indeed thrive, with Lennon mostly absenting himself from the band,” as Michael suggests? I’d say the answer is no. I read John’s alliance with Klein, and his behavior toward Paul during the late 60s until the breakup, as saying, in effect, “I’m more interested in reclaiming my role as leader, and my ascendancy over Paul, than in preserving the group.” And by the time of “Abbey Road” I think that was clear to Paul.

.

I think it’s certainly possible to take too romantic a view of “Abbey Road” as the Beatles’ inevitable swan song — especially if that means believing that “nothing good lasts.” But I also think it’s realistic to recognize that relationships are living entities that can be damaged beyond repair. Exactly where that happened, with the Beatles, is a matter for discussion, but it seems clear to me that they (especially Lennon and McCartney) reached that point. Certainly by the time Paul issued that mock interview with the “McCartney” album he was stick-a-fork-in-me done. Could they have gone on releasing music under the “Beatles” name without really being the Beatles any more, in the sense of having a live artistic collaboration founded on mutual respect? Sure. But I’m not sorry they didn’t.

“Let me urge anyone inclined to give up on Starostin’s reviews because of this short “Abbey Road” piece to take a look at his longer Beatles reviews …”

.

Full disclosure: I never read music reviews, not ever. They usually strike me as pompous and self-important, so I’m the last person that could weigh in on Starostin as compared to others. 🙂

I hope nobody gets the impression I was saying to give up on Starostin! I think he’s great — and the reason he’s great is his opinions are strong and clear and well-founded enough to foster a discussion like this.

“John in particular doesn’t want to pull together in the way the Beatles would have to in order to survive as a band.”

Indeed. There are four tracks on Abbey Road where John doesn’t even appear. His signature song on the LP, “Come Together,” was transformed under Paul’s direction in the studio (in steps that were outlined in a recent comment). “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” is a neat song — I’m glad it’s on the LP, but you could take it off and Abbey Road would still be, well, Abbey Road. Lennon dismissed Side Two as “junk.”

.

On the other hand, that was John in summer/fall 1969, when he was preparing for his “divorce.” A year or two later, he might well have found himself in a very different frame of mind regarding the Beatles. Just as you can’t see the Twickenham Sessions from the vantage point of Pepper, you can’t really say that the ever-changable John Lennon would’ve stayed filled with envy towards Paul and weird antipathy towards his own group. What drove the four apart, and kept them apart, was the stuff going on outside the studio (with the exception of Yoko’s bed).

John Lennon is not participating on four songs on Abbey Road. Well all right. Could be, on how many songs from the White Album can John not be heard.

e.g. on the first recording of ‘Come Together’ John doesn’t play any instrument, apart from singing and some tambourine…

The next day, July 22, Paul worked on the song with a lot of overdubs. On July 23rd the band was rehearsing for several hours before recording of ‘The End’, according to several sources with quite a lot of drive and musical leadership from John Lennon. Remember his musical ambition for a ‘massive’ guitar sound, and that includes recordings and live-performances of ‘Yer Blues’ and ‘Cold Turkey’, all played with his Epiphone Casino ES-230TD.

.

An artist who is practically absenting himself from the band, is not absent for less than a day… while of the other three players only Paul is in the studio, and John later reported he was disappointed if not a little pissed, McCartney didn’t want to share or left him the lead-vocal for ‘Oh, Darling!’.

.

The basic tracks of ‘Something’ were done with John Lennon on the studio-floor; after some rehearsing it was chosen that it was only George, Paul and Ringo that would play the basic tracks… Again, the artistic contribution of Lennon to Abbey Road appears a whole lot bigger than that which somebody who consciously absents himself from the band would deliver.

.

Yours is a reasonable reading, @rob, but just as much evidence exists for John’s taking a powder. Remember, exactly one month after the last session, he walked out on the band.

Lennon himself famously said, “I stopped doing all the little things.” I think it’s perfectly valid to characterize John’s attitude towards all things Beatle as half-committed at best during this period. If you wanna work super-hard to make him a full participant in Abbey Road, be my guest. I think he worked on his own tracks, got pissed the others didn’t stop the sessions after his car wreck, tried to divide the album up 50/50 with Paul (what about George and Ringo?), apparently had an “acrimonious argument” with Paul late in production, and finally quit the group. After the LP was seen as a a masterpiece, John went out of his way to badmouth it.

That sounds like someone who’s not really on board with a project but, as ever, your mileage may vary.

I agree “I want you (she’s so heavy)” is a cool track with a neat sound. John could still do great work when he gave a shit, but he often didn’t, especially when it was someone else’s song. That’s not how the leader of a band acts, and he knew it, because he didn’t stsrt behaving like that until White, when he “stopped doing all the little things.”

“Musically absent” is a kind way to describe John’s behavior after Fall 1968. “Actively disdainful” is probably more accurate.

@Michael–I agree. John broke up the band and basically behaved like a dick. When Paul was a dick it was in the service (he felt) of the music. But I don’t know how long George would have lasted with all those songs he wanted to record and his spiritual aspirations and Paul still insisting on 2 per album. All Things Must Pass was a deep and gorgeous record (except for side 4…)

You know, @Chris, I even like side 4!

The only way the Beatles could’ve continued, IMHO, was as an annual Christmas LP, where J/P/G all put their poppiest, most hit-making stuff. Which would have

1) made them all TONS more money;

2) allowed them to spend 49 weeks out of the year doing whatever they wanted;

3) gave their solo stuff a bigger profile.

It is peculiar to me that, the more George pursued meditation and spirituality, the more angry and obstinate he became about Paul (and later John). This is unusual.

If you and Nancy like him, his cred just went up in my books automatically. 🙂

John Lennon is ‘practically absent’ from Abbey Road… or worse ‘John Lennon mostly absenting himself from the band’

.

Of course – everybody has different opinions, and we love to love our individual tastes and thoughts and phantasies…

And facts do not exist…

.

So here’s John…

His art is dominating side A of ‘Abbey Road’ with ‘Come Together’ and ‘I Want You (she’s so heavy)’.

The latter, is the first and the last song The Beatles recorded/mixed together for the album ‘Abbey Road’. In February it was without McCartney that Lennon and Harrison drove The Beatles into a massive guitar sound, a variation on the loudest possible chaos Paul lead The Beatles into with ‘Helter Skelter’ – great solos by the way, of which really none appears to be by Paul.

To me ‘I Want You (she’s so heavy)’ is the Beatles almost crossing the blues line (sorry if I am wrong, I am a whitey without long hair and no beard, and I only drink beer during the summer in Austian mountains), maybe it’s not bluesy, but at least it sounds like they took a dive into a southern swamp, probably an inspiration to the Stax/Booker T sound John Fogerty went after with ‘Pendulum’. This is the same southern swamp Paul would later drive ‘Come Together’ in, with his piano-licks on Lennon’s request.

It was during, what I know, really really was, the last session all four of The Beatles were together in the studio, when they mixed ‘I want you (she’s so heavy)’ and put together the epic shape and order into that sonic adventure called ‘Abbey Road’.

.

On side B, it may be the beauty and positivity of ‘Here Comes the Sun’ that sets the mood, indeed, what an album opener that would have been, the 2nd Harrison would have got, after ‘Taxman’ in 1966. It is the heavenly and wonderfully recorded ‘Because’ that sets ‘Abbey Road’ sonically apart from most of their contemporaries. Crosby Stills and Nash had already given the world their ‘artistic baby’: the gorgeous unique west-coast voices on their first album in May 1969. The Eagles came a couple of years later with ‘Seven Bridges’ but take my judice advice: get an original ‘Abbey Road’ vinyl album and play it on the best record-player-cable-amplifier-speaker-set thinkable and there is heaven in your ears and head… so beautiful, such a unique sound, the greatest noise and the most beautiful harmonies are in Lennon songs, and the composition is as delicate as Lennon is capable of, like ‘Strawberry fields forever’.

‘Sun King’ is a Beatles’ Albatross swooning on a summerly breeze, with the typical Lennon/Beatly Spanish Italian word-play, forty years later still part of my sing-a-long-whistle-a-long while it is not a non-entity. Lennon absent? And how the #%$&# did Lennon became so happy? if I want to express my love in words to the one I love – I mean ‘love’, a variation of these words come easily:

“Questo obrigado tanto mucho mi amore, de felice carazón, que can eat it”

.

‘Mean Mr. Mustard’ and ‘Polythene Pam’ are nice 1968/1969 Lennon/McCartney songs where he gets close to the pop-song quality so typical for The Beatles. And bootlegs full of outtakes or the Rock Band game provide ample proof

.

or read what Lewisohn wrote a zillion years ago, when he was not yet the unsung hero of Beatles-history:

.

“The basic track of this double-recording was

taped during this 24 July session: bass, drums, electric

and rhythm guitars and a John Lennon guide vocal, and

once again this original tape displays the cohesion of the

Beatles as a musical unit, with a thorough understanding

between the four. All the basic ideas were there right

from Ringo’s delicately brushed cymbal which signalled

the start. Even when the session suddenly slipped into a

jam session – John singing a complete version of ‘Ain’t

She Sweet’ and then, clearly in Gene Vincent mood,

following with ‘Who Slapped John?’ and ‘Be-Bop-ALula’

– the sound, though husked and impromptu, was

also good and precise.”

.

Okay John dismissed Abbey Road… but who cares about the artist’s opinion about his or her own work. Bob Dylan thought ‘Blind Willie McTell’, ‘Dignity’ and ‘ Series of Dreams’ were unfit to release…

.

Sorry Michael; artistically, as a musician and composer, John was spot on and integral and indispensable during the recordings and on ‘Abbey Road’ – they were in it for the money and wanted to play… and play they did all four.

“Facts do not exist . . .”? I don’t understand what you mean here, Rob. But I agree with what I think you are saying about Lennon’s importance to “Abbey Road.”

Nancy,

the phrase: “Facts do not exist . . .” is my Paul to John on Ram… a confirmation of sorts that my words are only an opinion.

Hi Karen

yeah, that’s what he says, but does he believe it? This part of the conversation starts with his remark that somebody said it was about him… he then picks it up…

To me that is again about do we care about the artist or about the art. Most artist have no big ultimate intentions with their art, they make it up… and sometimes the argument changes… or when they hear other people explain what they see, hear or experience and they like it, they pick it up and make the argument their own… I don’t believe in myths.

yeah, that’s what he says, but does he believe it?”

.

This is my take on it: John wrote the song How Do You Sleep? about Paul as a response to RAM. It was an over-reaction of galactic proportions, and I think he later regretted it. The “it’s really about me” comment is Lennonesque for an apology of sorts, and maybe a tiny recognition that the song DID say more about him–his anger, his resentment–than it ever said about Paul.

.

Most artist have no big ultimate intentions with their art, they make it up… and sometimes the argument changes… …But some do. Artists who DO intend to communicate a clear and obvious message in their art are absolutely responsible for that message. You can’t say “well gee, I wrote a song praising ISIS, but just ignore the words and appreciate the melody–and if you don’t, then you just don’t appreciate a good song.” We are responsible for what we communicate. If we are wrong, we apologize. We make amends. The thing about music, however, is that there’s no takesies-backsies: once it’s out there, it’s out there. I think John’s backward apology–“the song is really about me”–was his way of making amends.

Karen, given John’s alleged psychological issues, as well as his addictions at the time (1971) is there any way to gauge just how deliberate or conscious John was of the damage he was causing with interviews like “Lennon Remembers” and songs like “How Do You Sleep?” How much of what John tells us in 1971 is a deliberate, concerted effort to destroy Paul’s musical reputation and diminish Paul’s contributions to the Beatles, and how much of it is simply adolescent John throwing a vicious, public temper tantrum, aided and abetted by Klein and Yoko, which he fully expects will blow over and everyone will forget about in a year or two?

Such compelling questions, @Ruth. According to Larry Kane, John’s default setting was the preemptive strike: attack first, apologize later. Given this, it wouldn’t be hard to imagine that John was essentially clueless about how damaging a song like HDYS or an interview like Lennon Remembers really was UNTIL everyone lost their water about it. (I recall that he was quite angry with Jann Wenner for even releasing Lennon Remembers as a book, presumably because he regretted his outburst).

.

John had always needed others–Mimi, Brian Epstein, Paul McCartney–for impulse control. When left to his own devices (and in the company of others who egged him on) his emotions went unchecked and his mouth went into overdrive. Did John intend to publicly flog Paul so brutally so as to destroy his reputation? I tend to think that John’s intention in sounding off–besides getting it off his chest like a petulant adolescent–was to only level the psychological and emotional playing field; “When I feel weak, I think Paul must feel strong.”

I think that’s probably right, Karen. However, I also look at the fact that “HDYS” was carefully rehearsed and produced. John may have wanted to see it as a momentary outburst, but it clearly wasn’t. From what I’ve read about the circumstances of the recording, no one except Ringo suggested John might be going too far with that song.

.

And that’s what’s really sad, to me. I can see John being carried away by his feelings, but find it harder to understand why no one close to him was willing/able to counsel him against expressing them in such a vicious and public way.

I also look at the fact that “HDYS” was carefully rehearsed and produced.

.

Oh absolutely @Nancy. It wasn’t a one-off, that’s for sure. But I don’t think HDYS qualified as a revenge-inspired dish served cold–it was vintage John, being all hot-headed and flying off to the studio to give Paul the what-for. All conjecture of course, but it seems so predictably John.

.

Edited to add that I second your thoughts about why no-one said “Whoa, boy.” With that thought, though, comes a followup thought: that there was no-one around who a) wanted to, b) was brave enough to, and c) had the requisite amount of influence.

Good comment, @Karen.

Re: Lennon Remembers: John felt that Wenner had reneged on their deal; he wanted the book rights for himself. By some accounts, he never forgave Wenner for it.

Thanks for that info @Michael re Lennon Remembers. I remembered reading about John’s resentment regarding its publication but couldn’t recall more than that.

.

“Probably any other musician in the world would have quit their band to play with Paul. Every other musician except the two who had played with him practically since they started playing music.”

Uh, not in the 1970s. Among the world of rock musicians in the 1970s, John and George were COOL. Look who they collaborated with during the decade: Eric Clapton, Delaney and Bonnie, Frank Zappa, Duane Allman, Elton John, David Bowie.

Paul was definitely NOT COOL among rock musicians. Look who he collaborated with during the 1970s: Denny Laine, Henry McCullough, Denny Seiwell, Jimmy McCulloch, Geoff Britton, Joe English, Laurence Juber, Steve Holly. Not exactly the same calibre of talent.

And it’s a fact that Henry McCullough, Denny Seiwell, Denny Laine, Jimmy McCulloch, and Joe English all quit Paul’s band.

Perhaps some of John and George’s perceived “coolness,” in the music world, in contrast to Paul’s “squareness,” was inspired by John, George, and Allen Klein’s anti-Paul propaganda campaign, and their repeated efforts to label him as a granny-song writing, pretentious social climbing, WASP-Jew marrying “straight,” who was breaking up the Beatles solely for his own selfish, classist reasons

and who had, according to Klein, only written a minor portion of the Beatles catalog anyway.

—

I doubt Paul’s legal victory over the other three Beatles inspired much camaraderie in the musical community.

Regardless, Jimi Hendrix wanted to collaborate with Paul, and send him a telegram in 1969 which, unfortunately, Paul didn’t get.

I tend to agree with you Ruth.

.

I would also add that John and George gained a lot of street cred from their public involvement with the many social causes swirling around them at the time. The late 60’s and early 70’s were a time of significant social change and rock stars who jumped on the political bandwagon were generally viewed more positively by an increasingly politicalized rock audience than those who didn’t. Paul didn’t grow his hair down to his navel, write protest songs (with a few regrettable exceptions) and otherwise identify himself with that crowd–and I think his reputation suffered for it.

That assessment is spot-on, Karen. I just finished Doggett’s “There’s a Riot Going On,” which makes it clear that rock performers, post-1968, were expected to pass some sort of political litmus test to demonstrate their devotion to the counter-cultural Revolution, and that the underground and rock presses castigated those rock figures which refused to promote their anti-establishment world view. There was a definite “If you’re not one of us, you’re the enemy” strain of thought, which is why John, Yoko and Klein’s portrayal of themselves as anti-establishment figures and their depiction of Paul and the Eastman’s as “straights” was so crucial; they were using the larger cultural and political divide as personalizing it amidst the politics of the Beatles breakup.

—

There’s a part in the book when the self-described “Dylanologist” Weberman ( I can’t remember his first name) — a fan who essentially stalked Dylan and pawed through his garbage in an attempt to decipher his lyrics and castigated him for failing to lead the revolution — got an audience with John, in late 1971, I believe, and spent the meeting catering to John’s ego, deciphering John’s Beatles songs, and expressing his belief that John had actually written a lot of Paul’s Beatles songs, as well. John had surrounded himself with these people in 1971 and 1972, yes-men telling him what he wanted to hear.

@Ruth, the guy’s name was A.J. Weberman, and he’s still around. IMHO, the politicization of popular culture that occurred after 1968 is an expression of the political impotence of the American Left in the wake of the assassinations, Chicago, Kent State, etc. If you can’t stop the war, you can at least levitate the Pentagon. Angry songs, angry comics, “radical chic,” the whole personal-as-political ball of wax — this is all frustration, once it became clear that the dominant culture was not going to change, and was prepared to use violence. Not for nothing did the New Left only really thrive and survive on college campuses, artificial (and one might say unimportant) protected spaces, where an artificial civility and hierarchy interested in ideas (and thus prone to “moral” leverage) held sway.

Webberman and Dylan had a famous series of phone conversations in 1971 that were released as a bootleg; you can find it on YouTube as “Bob Dylan Vs. AJ Webberman”.

For people like Webberman, I go to Dangerousminds.net — and sure enough, Richard Metzger did a post.

It’s worth noting that despite John Lennon’s anti-Eastman, pro-Klein zeal of the early 70’s, David Bowie (who once called Lennon his biggest mentor) ended up hiring John Eastman himself and happily had Eastman shepherd his career for the last 30some years of his life. Saving the Clapton-George friendship (which started back in the Beatles days) I think people over-estimate the willingness to hang out, snort some blow and make one or two songs in the 70’s as proof of eternal friendship. Bowie, for example, continued to having nothing but the best to say about John even long after John’s death, but while I’m sure he knew of John’s anti-Eastman agenda and the circumstances of the Beatles’ breakup, it did not prevent Bowie from collaborating with Eastman himself. He made his own decisions.

Also, despite not collaborating with those named people in the 70’s, Paul does have relationships with them. Paul and Elton John are friends (according to Elton, anyway) and Paul has collaborated with Clapton now a few times. Clapton, in fact, had nothing but the highest of praise for Paul during the Concert for George, stating how Paul missed George “as much – if not more – than anybody” and how Paul completely humbled himself for the cause. As for their own relationship, Clapton said, “A lot of times during our relationship, I found it very difficult to communicate my feelings toward George — my love for him as a musician and a brother and a friend — because we skated around stuff.”

The list of famous musicians who have collaborated with and/or expressed admiration for Paul is long indeed – and it’s not insignificant that more of them tend to be people of color and women from different musical genres, not just the typical 1970’s stadium rock white guys.

Good points, @Rose.

I think John Lennon’s colleagues were very well aware of how suspect his judgment was — and how influenced he was in those decisions by his wife who, for all her intelligence and acumen, had no experience in the big-time world of lawyers and agents, promoters and record executives (I don’t mean groovy A&R men, I mean the old white guys in suits who signed the checks). John Lennon’s opinion of John Eastman circa 1969 would matter less than nothing to David Bowie. Elton and Bowie revered John as a musician, not as a businessman.

Looking at Eastman’s obituary in The New York Times, it’s interesting that several of his clients are refugees from horrible managers; in addition to Paul, there’s Billy Joel (who was swindled out of $90 million), and Bowie (who was screwed by Tony Defries).

TL;DR — history proved John and Lee Eastman were the good guys in 1968-1971.

@ Rose, I must have seen that. I read somewhere that Paul McCartney is highly admired and respected by most composers, songwriters and musician in every genre. Thats no small feat by anyones definition. I know I’m being redundant to what you have said, but I just like saying it so much, and it bears repeating! After the unfair drubbing, and lasting effects his reputation received from bitter heart, New Establishment music critics of the 1970s, I’m glad to know that as time went by, his musicality (?) has come out of the “wilderness” and is being received and appreciated by a younger generation of music lovers the world over.

@WaterFalls, I just recently read Elvis Costello’s memoir, and one of the things that struck me is not just his admiration (being a Liverpool native and Beatlemaniac, Elvis of course admires all the Beatles) but also the tremendous affection and genuine love he has for Paul. And – aside from his close family – Elvis does not strike me as someone who gives out such warm and tender feelings easily, especially to fellow people in showbiz.

As for Paul withdrawing from the 70’s rock social scene to some extent, I was reminded of this bittersweet quote Pete Townshend gave to Danny Fields:

“Linda was very, very pro-active in their social life. When they were driving through this town, she was the one who used to get him to come and visit, even made a couple of surprise visits. She was the one who would call me and then put him [Paul] on the phone, and we would talk. Then he would be open and entirely accessible, but it was Linda who was always reminding him that he really had friends, that he was likeable as a person, that he could reach and be reached . . . She was constantly there with the idea that there is love between people when the tape stops running and the curtain is down.”

I’m so glad that Paul and Linda had each other. She really was so good for him especially when it seemed like the whole world was against him. I imagine it would really do a number on a person, when it seems like the whole world loves you, then

it seems that the whole industry hates you, and everything about you, and everything you do. And leading the charge is your boyhood hero, best friend and songwriting partner. Ooh, that’s gotta hurt! Her death for him and their family was a great loss, but I like to believe that Paul gets comfort knowing that love never dies. Mother Mary (who spoke words of wisdom to him) John (in his healthier frame of mind) and lovely Linda, who was his love and rock. And now his has Nancy who seems to have his best interests at heart. Paul was and is truely blessed.

@Water Falls (and all) — let’s not overstate Paul’s predicament in 1971. The whole industry didn’t hate him or what he did. A small but vocal community of self-appointed tastemakers didn’t like him and thought he was square.

Did he get treated fairly? No. But was Paul a pariah? No. We mustn’t give Rolling Stone and ilk a kind of omnipresence they didn’t have.

@Michael G, of course you are right. That’s why I said “seemed like” (maybe at least to Paul) but you are correct.

Point taken, @J.R., but John and George were guest-stars on other people’s records; they weren’t forming a band. That’s not the same thing. Borrowing John Lennon for a track isn’t the same as forming Wings.

If you wanna do apples-to-apples, put Denny Laine and Lawrence Juber up next to Elephant’s Memory, “a politically active street band.” From that perspective, Laine and Juber may actually be more worthy collaborators, all due respect to Elephant’s Memory.

Among the world of rock musicians in the 1970s, John and George were COOL. Look who they collaborated with during the decade:

@J.R, I don’t think rock musicians necessarily thought that Paul wasn’t cool or they didn’t want to work with him. I think it was the other way around. Paul was very closed off in the 70’s. I think Paul was the one who didn’t want to collaborate, not other famous musicians. Perhaps Paul didn’t want to work with musicians who he saw as friends of John and George, and or had worked with them. Perhaps it was also part of Paul’s insecurities at the time. He just wanted to be with his family and musicians that HE had picked and who HE decided to work with. And for a lot of reasons, he chose musicians who were not well known. Perhaps this was part insecurity and partly a control issue. Paul didn’t want to lose control of a situation at this time.

@ J.R, Clark, Paul may not have been YOUR definition of COOL, but he most definitely WAS. Instead of being a stereotypical raging rocker, who after giving a raucous performance on stage, goes to clubs or hotels to rage and trash everything, to middle finger everybody including fans, Paul gives his all to his fans on stage, leaves the stage along with Linda to do the coolest thing ever. They go on to being normal parents to their children, who they brought along with them on tour, so they can all be a family together. May sound square, may be square, but it most definitely was cool. Paul was being a family man, YEARS before Lennon was doing it and being praised for it, like he invented it. John and George may have collaborated with “titans” of cool in the industry, but one could argue, they needed BIG CRUTCHES to lean on, to hold them up because they didn’t have Paul McCartney to shore them and their confidence up. One could argue.

“Paul gives his all to his fans on stage, leaves the stage along with Linda to do the coolest thing ever. They go on to being normal parents to their children, who they brought along with them on tour, so they can all be a family together. May sound square, may be square, but it most definitely was cool. Paul was being a family man, YEARS before Lennon was doing it and being praised for it, like he invented it.”

.

A zillion times YES. One of these days rock biographers will realize that the man had stones and deserves their absolute respect.

Like Huey Lewis and The News sang in 1986 IT’S HIP TO BE SQUARE!

So Paul was trailblazing a path for Lennon and others to follow, Rocker Family Man.

Paul along with Linda, marched to the beat of their own drum, they followed their own rules, put their family first and brought up their children, regardless of how “cool or square” others may have thought they were.Their children are pretty well turned out. That my friend, IS COOL!

Water Falls, this reminds me of the conversation Chelsea QW and I were having on the “Lester Bangs” post, about Bangs calling Paul a “librarian.” Chelsea responded that Paul is the “sexy librarian” of the Beatles, which I second. There are now whole Tumblrs about his 1960’s and 1970’s sweaters, for instance.

.

The one thing it was NOT COOL to be in the late 60’s to mid 70’s, in rock terms, was a publicly devoted family man. I give Paul much respect for bucking that trend.

“The one thing it was NOT COOL to be in the late 60’s to mid 70’s, in rock terms, was a publicly devoted family man. I give Paul much respect for bucking that trend.”

Amen Nancy.

I agree, @Nancy, @Water Falls. Paul also did his own thing musically even if it wasn’t cool. Look at some of those loopy lyrics! Magneto and Titanium man? Uncle Albert? That takes guts 🙂

@Chris, well as they say, no guts, no glory. Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey hit #1. I love the “loopy” lyrics in Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey because I think they are coded for a “particular listener”, and are just to be enjoyed as a funny song by the “average” listener.

I also like Magneto and Titanium Man. It’s crazy and fun, what’s wrong with that? As for loopy lyrics goes, a lot of music has silly lyrics but the song can still be good, for instance, ‘Goo goo ga joob’!, ‘Sweet Loretta Martin, thought she was a woman, but she was another man.’ Nearly all of Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.

Sun King’s ‘quando para mucho, mi amore de felice corazon, mundo papparazzi, mi amore chica ferdy parasol, cuesto obrigado tanta mucho que can eat it carousel’. Nonesense lyrics but lovey song anyway. Have I made my point?

Yeah @water falls, no need to convince me. You’re preaching to the choir

(smile) 🙂

Paul’s lyrics are either too cryptic for us mere mortals to decipher, or just plain (sorry Macca) dumb. We know he’s capable of more, but he chooses to hide behind banality as a sort of protective shield, I think.

@Karen. Or he just has a good melody and wants to get a song out and isn’t bothered about the lyrics.

OMIGOSH! @ Karen, I just re-read my comment “I love the loopy lyrics in Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey, because I think they are coded for a “particular listener”, and are just to be enjoyed as a funny song by the “average listener”. WOW! How condescending I sound, like I’m “all that.” I now “get” your comment about “mere mortals”

I apologize to anyone who read my comment and justifiably took offense. What I meant to say was “I think they are coded for a “particular listener (John Lennon) and are just to be enjoyed as a funny song by the “average listener” (meaning the rest of us). I meant no disrespect to any of you, and I hope my sincere apology is read and accepted.

” I just re-read my comment “I love the loopy lyrics in Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey, because I think they are coded for a “particular listener”, and are just to be enjoyed as a funny song by the “average listener”. WOW! How condescending I sound, like I’m “all that.” I now “get” your comment about “mere mortals”

.

Oh no, Water Falls—-my comment was in no way intended for you! I didn’t think you sounded condescending at all, quite the opposite. I love your take on McCartney lyrics because I never considered them in the context in which you present them. Keep it up!

Karen, while I definitely agree Paul does phone in lyrics on occasion (we could all give examples) I think he is very often an AMAZING lyricist. And some of his best shit is head-scratching stuff.

Why, just a few days ago I listened to Abbey Road and heard (for the FIRST TIME IN MY LIFE!) this amazing masturbation metaphor: “Now she sucks her thumb and wanders by the banks of her own lagoon…” That is some dirty, sexy poetry there! Paul should be writing r-n-b slow jams. 🙂

“Why, just a few days ago I listened to Abbey Road and heard (for the FIRST TIME IN MY LIFE!) this amazing masturbation metaphor: “Now she sucks her thumb and wanders by the banks of her own lagoon…” That is some dirty, sexy poetry there! Paul should be writing r-n-b slow jams. :)”

.

Sly devil–I’ll have to go back and have another listen!

“Mumbo” is a great Paul song, and I swear I can’t understand a single word he’s singing. Can anyone help?

@ Sam, Yes it is a great Paul song, and you’re not the only one having a hard time figuring out what he is singing, it sounds like he’s singing while holding his tongue. I looked up the lyrics but I must say, some of it seems not like what your’re hearing.

.

Take it Tony!

Well, your love in my mind, oh woman I’m breakin’. My minds’ gotta take, no one’s gonna break ya

Ooh, come on keep it on playin’, Come on keep it on play. Come keep it on player. Come lose it or player.

Well! My mind is in love. My mumbo will break ya. Well our love hasn’t made. The mumbo will break ya.

Ooh come feel it on playin. Come keep it on play. I don’t see any number, I don’t see an old lady.

Ah yeah yeah

I don’t beat a drum player. But I made alright. I am keepin’ a layer. Come I made it alright. Eheh Eheh

Eheh. Eheh. Eheh. Eheh.

Ooh. Come and see me I’m a player. Come on feel it I play. We’re not feelin’ a play out. No one think of a way

Ooh!

Well! Lady on my mind I think I should make love. Well my mind hasn’t made all up, can’t go to maintenance.

Ooh, you don’t seem to me, you don’t seem to me get any maintenance.

Well on my mind my mumbo will make you. Well down in my mind my mumbo will break you

Ooh, come on keep it on playin’. You just keep it on playin’. You just keep it on playin’

Ooh. You just beat them all. Aah

Aaah, your love is a waste. Come on honey let’s make love. Well my has been made up

Aaah, Aaah, Ah, Ooh

Well! I found my love, I make it well…

I’ll see if I can make more sense of this later. Probably not because I’m a mere mortal too. But my son-in-law is taking us all out for dinner…so…gotta go!

This is an interesting little tidbit from Metro Lyrics:

‘Mumbo,’ as recorded on Wild Life (1971), consists entirely of

screamed nonsense syllables in a concerted vocal tour-de-force. It is rumoured,

however, that Paul has used actual words when performing this song in concert.

You’re deflecting the point by bringing up Paul’s personal life. Fine, we can discuss that. Devoted family man or not, it is a fact that Paul McCartney spent exponentially more time in handcuffs, before a criminal court judge, and/or behind bars, than John, George, and Ringo combined.

However, I am discussing Paul’s reputation and credibility as a rock musician in the early 1970s. In the world of rock music at that time, Paul was considered a lightweight compared to the early-70s Stones, Who, Led Zeppelin, hell, even Grand Funk Railroad! Paul wasn’t competing against them, he was competing with David Cassidy and Marc Bolan.

RAM was a nice album, but it in no way was the artistic equivalent of other 1971 releases like Led Zeppelin IV, Who’s Next, or Sticky Fingers. To argue otherwise is to be willfully obtuse.

You’re getting a little hot here, @J.R. —

Paul spent time in handcuffs for the kind of behavior (drug use) that John, George, and Ringo did incessantly throughout the Seventies. Because Paul got caught for bringing pot into Japan (N.B.), we should label him a bad hat? When Lennon was actually scoring smack in New York in the early Seventies? Or George and Ringo were hoovering up all white powders? I don’t think that’s fair.

As to “Paul’s reputation and credibility as a rock musician in the 1970s” that’s purely personal opinion, and you’re entitled to yours. I felt much the same way until I did some digging through Rolling Stone circa 1975 for a project several years ago. In the run up to their US tour, McCartney (and Linda!) were covered with the same seriousness and respect as any of the bands you mention, and they were covered a LOT. Venus and Mars was covered a LOT.

On the other hand, in the issues I read, Lennon was covered when he was a sideman for Elton, but otherwise, nothing. And that was the year he released “Shaved Fish” and “Rock and Roll.” To me, the closest analogue to McCartney was Stevie Wonder — even though I like Stevie’s 70s stuff much more than I like Paul’s, both were considered consummate pop singers who could rock (or funk), and while there were harder people, or newer people, these guys were STARS. Both could be seen as lightweights in comparison to other performers, but they were both extremely popular, and not just with the David Cassidy/Bay City Rollers set.

But these issues are entirely judgments. Let’s let a thousand flowers bloom.

@JR: I wouldn’t argue that any of Paul’s 70’s efforts are necessarily artistically better than the heavyweights. I would just say it takes a kind of individualism and yes, guts, to write songs the way you like to write them without trying to be what someone else, or the culture, tells you is “cool” or “deep.”

I also don’t think the attitude of the law towards a person is necessarily indicative of the strength of their moral compass.

The point I was making was, there is more than “one right way” of being cool. We all have our own definitions of it. Yes Paul spent “…more time in handcuffs, before a criminal court judge and/or behind bars than John, George and Ringo combined.” Which means nothing as far as his basic decency was/is concerned, since great men like MLK, Ghandi, Mandela, were also arrested and jailed, not for breaking drug laws, but breaking unfair oppressive laws. Even Jesus was arrested, tried and executed for claiming, in essence he was “bigger than Caesar”. (yeah, I went there)

Yes in the early 1970s Paul’s reputation and credibility was tagged lightweight by the rock music critics who were angry with and blamed him for breaking up their “religion” The Beatles, so Paul had to be punished for that with an all out campaign by the music press to bash and trash everything he did. Perhaps too in some quarters his comtemporaries in the rock music world thought he was “light weight”as well. I doubt seriously that Paul was “competing with David Cassidy and Marc Bolan, or ANYONE, for that matter. He was more than likely competing with himself. And since he built WINGS into a pretty ace band, I’d say he didn’t do too badly. Music critics today recognize RAM, as more than a “nice album”. It is considered a masterpiece, by critics and fans alike, me included, and I reject the label of being “willingly obtuse”, although Mike G’s response to you, was articulated better than I could have done, I felt nonetheless I should respond to your comment, and I hope that I haven’t irked you in some way, since this is suppose to be a civil discussion.

@ J.R. said: “In the world of rock music at that time, Paul was considered a lightweight compared to the early-70s Stones, Who, Led Zeppelin, hell, even Grand Funk Railroad!”

..

While I think that’s generally true (with Band On The Run being the notable exception), it’s telling that music critics have since revised their opinion. Has the passage of time just softened everyone’s opinion, or are people finally willing to give McCartney his due? Here’s a sampling of how Ram has faired decades later:

.

I don’t know if the apology I wrote as a reply to @ Karen will be seen since it’s a bit upthread. Since it is meant for everyone it bears repeating. I apologize for the arrogant tone of a comment I made, ‘I love the loopy lyrics of Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey, because I think they are coded for a “particular listener” and are just to be enjoyed as a funny song by the “average listener”. What I meant to say was “particular listener (John Lennon) “average listener” (the rest of us) and not meaning to imply that “I” am some elevated “particular listener”.Please pardon my foot-in-mouth malady. I’ve graduated high school but never attended higher education other than the school of life. Not an excuse for my embarrassing faux pas, but might be the reason for future blunders.

What I meant to say was “particular listener (John Lennon) “average listener” (the rest of us) and not meaning to imply that “I” am some elevated “particular listener”.

Water Falls..no need to apologize. I knew exactly what you meant. Didn’t think twice about it. So it’s all good. Enjoying your comments along with everyone else’s comments. Unless someone did get annoyed with you…I haven’t read every comment in this thread. Anyway maybe I’m speaking out of turn but I don’t see how anyone here would have misinterpreted what you meant.

I love the loopy lyrics of Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey, because I think they are coded for a “particular listener”

Speaking of which, this is very interesting. I never knew, or thought Admiral Halsey was a coded message to John. Can you say why you think this? Is it something you heard or read somewhere, or is it simply a feeling you have personally? I know Paul has said that the song is based partly on his real life Uncle Albert who was married to his Auntie Millie. It seems Uncle Bertie might have been suffering from some form of dementia and actually believed he was ‘Admiral Halsey’. So the song seems to be based on actual events that Paul put into the song. I don’t know if everything is an Uncle Bertie reference though. I’ve always thought the butter pie thing was based on an actual event also. But maybe he was also sending a message to John in certain parts.

@ Linda, I’m one of many who believe that Paul and John wrote songs to, for, and about each other throughout their partnership in The Beatles and post break-up. I know they wrote songs about other people but I think sometimes even those, in whole or in part, also became about each other. It seem to be one way they could communicate when they couldn’t talk to one another. I admit that I could be 100% wrong about it, and the interpretations I gleam from their songs could also be wrong, but it’s fun speculate about it sometimes. I recently did an interpretation of Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey on a post here. Here it is without the actual lyrics, to go along with it, so as to shorten the length of this post.

.

Paul speaking for himself and Linda, or using the “general we” or “royal we” sarcastically using Uncle Albert (code for Albert Einstein, genius)

.

We’re so sorry if we hurt your feelings, Genius, because it’s all about YOU and YOUR pain. My pain doesn’t matter although I’m feeling gutted and empty and I’m going to cry!

No I haven’t heard any news reports or gave any new interviews about you. If you have said or done anything that hurts my family, (wife, kids, in-laws) I just may notify you that you’ll hear from my lawyers.

I’m sorry but I’m too busy, NOT being busy, kinda like when you couldn’t give me, the time to talk to privately because you were too busy being attached to Yoko.

John reaches out across the great divide. He’s been thinking a lot about Paul, wants to talk face to face but wants assurance that he’ll welcomed, not have the door slammed in his face when he shows up, or he won’t bother. Paul still bruised and bitter about the break up, the Lennon inspired hazing from the rock music press, hears John’s request, decides to swallow his harden pride, and agrees to meet his old friend. The two make plans and synchronize schedules.

Yoko discovers John and Paul’s plans, feels her cushy lifestyle is threatened, plans for fame for herself through John are jeopardized, flies into action, manuvering, manipulating, erecting roadblocks, obstacles, barriers, to thwart the former partners plans of meeting without her being there with John. She succeeds.

John informs Paul things have come up, there are unavoidable changes in their plans to meet and he doesn’t know when their schedules will permit a get together. Paul finds a way and eventually flies to New York City to meet with John. The healing starts.

That’s my take on it anyway. Again I can be wrong in my speculations and interpretations. It may very well just be about Paul’s Uncle Bertie. However I’m not the only one that sees a lot of John and Paul in their songs about other people. So therefore, I’m not a “lone nut”! 😉

You’re so sweet, Water Falls. 🙂

.

I replied earlier but ditto on the thread location–I didn’t think you were being condescending at all. My “mere mortals” comment was a reference to how esoteric Paul’s lyrics can be sometimes. It was just a joke, is all.

Thanks @ Karen, it is such a relief to know I haven’t offended you or others here.

No worries. 🙂

Steven Hyden, writing for The A.V. Club, said that the “lightweight” style that was originally panned by critics is “actually (when heard with sympathetic ears) a big part of what makes it so appealing.”

–

I don’t understand how RAM could ever be considered lightweight. I just…. WHAT? It’s filled with raw emotion and some pretty scathing lyrics. Are rock critics really so stupid and shitty at their jobs that they can’t hear past a pretty melody? I mean…. WHAT!?!? That’s not a matter of personal taste, that’s just…. dumb.

I’ll try not to rant too hard about this, as it’s one of my favorite topics 😉 but in regards to the “cool” debate…

If we’re honest about this (and come now, it’s 2016, let’s all be real for a minute), I think it’s clear that there was a very MALE reaction/discrediting campaign against Paul in the 70’s by the “rock critic elite” (insert eyeroll here). There was always this male resentment (which John Lennon personifies so acutely and actually gives voice to post-break up) of Paul for his popularity and sex appeal to women. The constant rebranding of Paul as “lightweight” is to me blatantly misogynistic (and probably at least a little homophobic). The irony is that being a devoted family man did NOT in any way diminish Paul for the vast majority of his female fans. That’s a fucking PLUS. Paul being HIMSELF in the 70s: the swishy, long-haired dad with his no-make-up-wearing, hairy-leg wife and a bunch of hippie-looking rugrats crawling all over him, is AMAZING and totally revolutionary. To call it “uncool” is to be totally oblivious to the fact that Paul actually defied more gender stereotypes than many, most or possibly all of his male contemporaries in the 70s. Not by wearing make-up or dressing in drag but by actually LIVING HIS LIFE in public, without apology. His work reflects all that, IMO. A willingness to resist trends, to be true to himself, to make music HE likes.

Being lightweight? What’s that even supposed to mean? Is that a criticism that his music is shallow or that it’s too happy? “Lightweight” is not a real criticism, it’s a buzzword. You need to qualify that with some actual substance. Actually deconstruct Paul’s stuff. Some stuff it is better than others, but it will all stand up.

Here, here! I love it when one of you gives voice to a feeling I have but can’t seem to put into words! Hallelujah and Amen sister!!!

“The irony is that being a devoted family man did NOT in any way diminish Paul for the vast majority of his female fans. That’s a fucking PLUS. Paul being HIMSELF in the 70s: the swishy, long-haired dad with his no-make-up-wearing, hairy-leg wife and a bunch of hippie-looking rugrats crawling all over him, is AMAZING and totally revolutionary.”

.

Chelsea, you crack me up 🙂 This is so true– Paul personified cool and original.

.

Some stuff it is better than others, but it will all stand up.

.

Here’s something I’ve noticed: I appreciate more and more certain Paul albums that I originally wasn’t impressed with. “Wings Wild Life” for example. I bought it when it was first released, and I guess I was hoping for Abbey Road II. I played it a few times and… ehh. Filed it away. But lately I’ve been listening, and I think it’s great. In 2016 I’m freed from my Abbey Road expectations, and accept “Wild Life” on its own terms. Maybe I’m entering my second infancy, but I hear it with the open ears of an infant.

.