- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

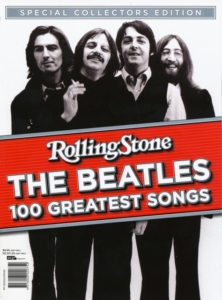

I noticed a few commenters had mentioned Rolling Stone magazine’s recent “500 Best Songs” list, and since I had a few thoughts about it myself, I wanted to set them down in the quickest and dirtiest fashion. Don’t take any of this too seriously, please. I have a headache and am avoiding work.

I noticed a few commenters had mentioned Rolling Stone magazine’s recent “500 Best Songs” list, and since I had a few thoughts about it myself, I wanted to set them down in the quickest and dirtiest fashion. Don’t take any of this too seriously, please. I have a headache and am avoiding work.

What is Rolling Stone, anymore? I’d argue that this latest iteration is no more classic Rolling Stone than if I scratched out “Hey Dullblog” and wrote “Rolling Stone” on my screen in grease pencil. It’s a different publication in a different format, with different readers and a different relationship to its readers, created by different people, for different owners, in a different era. And this list is an attempt to assert authority in a maddening age where even the idea of authority is suspect. The problems we’ve had with commenters here on Dullblog stem from this very issue. Who am I, the proprietor of the blog, to say that commenter x is wrong about Lennon’s mental state in 1968? The answer is: nobody. Who is Rolling Stone, or the owners of that name, to say that “Respect” is fifteen slots better than “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”? Once again, nobody. It’s not journalism, but a subtle kind of trolling, and I’ve fallen for it. Save yourselves! Stop reading now!

What is being judged here? Sales? Influence on musicians? Critical opinion? Industry fashion? Some impossible-to-define artistic relationship pop music wishes to have with the ongoing turmoils of America or the world? I love Sam Cooke and “A Change Is Gonna Come,” but who in the world has ever claimed that’s the third best song ever? What relationship does this ranking have to do with One Night In Miami (2020) or The Two Killings of Sam Cooke (2019), two suspiciously recent releases in a medium which shapes our culture powerfully, effortlessly, like music used to? Should currency have anything to do with a Best Songs list?

If you asked me, Respected Comedy Professional, to list the funniest movie of all time, my short list would reflect my own era and idiosyncracies and what I’d seen recently. And out of that group I would pick Life of Brian over several other really funny movies, because I believe it talks about an important issue (religion, and Christianity in particular). But I’d be lying if I said it was objective, or even very revealing.

I was twenty when “Fight The Power” came out and still remember the first electrifying time I heard it—but it’s not anything better than “Satisfaction,” and you all know how much I dislike the Stones. Once again, one wonders how much of that song’s position comes from it being affiliated with Do the Right Thing and Spike Lee’s next picture, Malcolm X? (Which also featured “A Change Is Gonna Come.”) What if it had been on Girl 6? In the entry for “Fight the Power,” its importance is summed up thusly by a member of The Bomb Squad: “I think it was Public Enemy’s and Spike Lee’s defining moment because it had awoken the Black community to a revolution that was akin to the Sixties revolution”—but is that really so, historically? “Akin” is doing a lot of work. Was there, objectively, a Black revolution in 1989 of the scope, impact or permanency of the Civil Rights Movement? Or is that Hank Shocklee’s personal feeling—no better or worse than my own personal feeling about Life of Brian? To me, part of the what gives BLM its terrible urgency is that songs like “Change Is Gonna Come” and “Fight the Power” light up the charts…and Black citizens keep getting shot, year after year. What does it mean about the power of popular music, and culture in general, that this rolling tragedy continues unabated? Does it not suggest that culture is not functioning as we hope it might? That great songs perhaps mean so much less than people like Rolling Stone wish they did? Or comedy matters less than I wish it did? This is not a quibble; if the practitioners of an art don’t ever develop that kind of seriousness and nuance, what hope is there for the audience?

This whole list is an assertion, a statement of what pop music should be and do, decades after Rolling Stone had any reasonable claim to that kind of authority; and it stinks of a magazine haunted by criticism leveled at a bunch of people no longer in the building.

What is Rolling Stone, anymore?

We know what Rolling Stone was from 1967 to roughly 2000. It was the primary expression of Boomer culture in print, a magazine founded by Jann Wenner, who embodied his brand only slightly less totemically than Hugh Hefner epitomized Playboy. First focused on rock and roll, RS almost immediately expanded into politics (somewhat successfully) and then general entertainment (very successfully). But classic RS was always a music magazine, not least because for the Boomers, music is very, very important. To a lot of Boomers of my acquaintance, what you listen to matters in a way that people my age (52) find rather weird. The idea that liking say, Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks reveals anything important about you as a person…huh? I can’t speak to younger generations, but I suspect that for most people under 60, popular music only matters that much to musicians and critics.

Yet this musical taste-as-virtue is at the heart of Rolling Stone, and its habit of list-making, which first took root in the 1980s, as America began to turn away from the Sixties for good. Rolling Stone‘s historification of rock really began with the death of John Lennon. As the old warhorses stopped dominating the charts, Rolling Stone bequeathed them a reservoir of importance it could control: historical relevance. In this way, Pink Floyd and Led Zep became Important because they had dominated rock in the early 70s. They were part of Rock’s story, thus they could stay in the cultural spotlight long after their sales justified it. In this way, Paul Simon became Important, because Graceland, because Apartheid, which made him Historical like Nelson Mandela and Stephen Biko were.

Is this total bullshit? Maybe. But also maybe not; I’m not a Boomer, and I’ve been obsessed with the Beatles since before I could speak. There is something about certain artistic forms in certain eras. Only time will tell if the Beatles and the Stones will last, but my guess is they very well might. Conversely, it seems unlikely that Outkast’s “Hey Ya” (#10) will have ongoing historical impact, and that’s okay, but wishing won’t make it so. It only reveals popular music to be splintered, strangled by digital culture, something close to fashion with its priesthood and its trends, an interest that wanes for most. That wasn’t what the old Rolling Stone aimed for; they wanted rock to be Great Art, not trendy fashion. And at its best, it was.

My problems with Wenner’s Rolling Stone are many and well-aired on this site. Via Wenner’s domination of his editorial staff, it firmly represented both the opinions of, and the cultural hegemony of, the Baby Boomers to the exclusion of everybody else. But that was kinda the point. Prior to the Boomers, the musical tastes of young people were often disregarded; now, they are the only ones who matter, which is why Robyn’s “Dancing On My Own” is listed at #20. Who is Robyn? What is this song? Why is it one spot higher than “Strange Fruit”? Why is “Strange Fruit” the only jazz song in the top 50, when jazz is arguably the single most important American contribution to world musical culture? People lost their freakin’ minds over Charlie Parker. He was, like, the Olivia Rodrigo of his day. 🙂

Don’t get me wrong; I like that Rolling Stone is attempting to be diverse, even if it is decades late. Even at its height, RS didn’t even represent big swaths of Boomers, much less the rest of us. But demographics, capitalism, racial history, and regional biases meant the portion of the Boomers represented by RS held outsized sway within our media in 1967, and 1997, and today. That gap has been filled by…the flavor of the minute, and that’s what this list shows so clearly and painfully. We’re on our own, free to make our own choices out of limitless options, and if there’s one thing our current politics shows, it’s that most of us are totally at sea. We desperately need curation, and not the kind that’s based on whatever movie you saw recently.

Wenner’s dream of capitalist counterculture—love it or hate it, you knew what it was, and so did Rolling Stone. The current thing bearing its name is both much more, and much less. It’s a music website aimed at young people, owned by Penske Media Corporation. There is no reason to assume that today’s iteration of Rolling Stone has anything important to say, or indeed any reason to exist other than commerce; there’s a bit of politics there which I happen to agree with, but I know too much about magazines and media corporations to think it’s more than skin-deep. Yes, we all love “What’s Going On.” The chairman of Exxon probably loves “What’s Going On.”

Today’s Rolling Stone wouldn’t be a magazine, wouldn’t be ad-supported, and wouldn’t be about music. Today’s Rolling Stone is a million online communities, spewing out memes on message boards. The form of this list dooms it to uncoolness regardless of content; it’s fair to ask who is this even for? My answer would be: Rolling Stone. This list is an editorial exercise in tandem with the marketing department; it is staking out territory, a niche to serve and defend. The moment the internet splintered us into infinite pieces, the job of every cultural institution changed from gatekeeping to something much grubbier: pandering. Cultural institutions now have to market themselves endlessly, in the hopes of gathering a big enough crowd to sell a couple of ads. Identity is endlessly tweaked based on surveys, market research, the wishes of advertisers, and pageview metrics…which is to say there’s no identity at all.

To some degree, this was always the case. Because of who owned the magazine, and who bought the ads, and who bought the products showed in the ads, Rolling Stone consistently gave Boomer warhorses like Dylan and our beloved Fabs more cultural space than they deserved. Or did it? I’m going to stop soon, but I wonder: Is the Baby Boom generation special?

I think it might be. The experience of the Baby Boom generation is really quite unique in world history. Given the turn away from education and social services since 1980, the Boomers are probably going to be the best-educated, best-fed generation ever, and probably the last one before Global Warming changes life on Earth irrevocably. The Baby Boom generation combines sheer demographic weight with a one-way monocultural mass media that gave them a strong feeling of shared identity based on shared experience. Ask a Boomer if they watched Oswald get shot on TV, or The Beatles on Ed Sullivan, or the Moon landing. Chances are, they’ll tell you they did, and have strong, similar feelings. That’s not what it’s like to be alive today, or how we consume media.

Other generations had had shared experiences of a sort—”the Lost Generation,” for example—but once the central event was done (in that case, WWI) life’s diversity reasserted itself. The Boomer dream has never ended, and will likely never end. The media has reflected the Boomers back to themselves incessantly—I might throw a little shade at “Hey Ya” but truthfully I’m glad it’s on there. One generation will control the narrative until they die, and that’s completely unique in human history, as far as I know. They’re going to carry Lorne out of Studio 8H in a pine box. Clint Eastwood is still making goddamn movies.

So, in that world, isn’t Rolling Stone‘s new list a good thing? Sure! I can’t see who it hurts. It’s a little overinvested in the idea that Music Creates Change, which I don’t see a lot of evidence for, but whatever—comedy doesn’t create change, either. Whatever the lists say, The Beatles will still be the Beatles, even if they’re not cool to music critics. They’ve never been cool to music critics—with the possible exception of about four months in 1967. But that’s another post altogether.

I’m opening comments to this one. Be nice, please. And don’t take this too seriously.

Fascinating take, Michael. And I’d love to follow up on two points that aren’t the most important part of that take.

“If you asked me, Respected Comedy Professional, to list the funniest movie of all time, my short list would reflect my own era and idiosyncracies and what I’d seen recently.”

Would you, RCP, list the funniest movie(s) of all time?

“Whatever the lists say, The Beatles will still be the Beatles, even if they’re not cool to music critics. They’ve never been cool to music critics—with the possible exception of about four months in 1967. But that’s another post altogether.”

Wait — WHAT? Would you please postpone whatever else you’re doing with your life and write that post NOW?

Great points, Michael. I agree that “Rolling Stone” is entirely a (pretty empty) brand at this point. And to the degree that this list and other RS ones like it have any cultural currency, they derive from their being promoted under that brand banner. I just wonder how much currency is really there now. In a world of clickbait and listcicles, this is just more of the same kind of thing.

And it seems clear that, as you say, this list is very driven by what’s in the public eye right now. It sure doesn’t seem like a coincidence that “Respect” occupies the top spot at the same time a biopic of Aretha Franklin bearing that title has gotten a lot of buzz, for instance.

Ultimately what irritates me about this list is that the project itself is ludicrous. What does it even mean to make a list of the “best” songs when you’re talking about multiple decades and wildly divergent genres? It seems purely performative, just saying that “Rolling Stone embraces all kinds of music now and is no longer in thrall to the Jann Wenner days.”

And I mean, I’m no fan of Wenner, but I don’t like the kind of critical incoherence this list represents any better. The only reasonable critical path forward, to me, is acknowledging the fragmentation of music (or any popular culture) and making quite specific “best of” lists. Trying to make popular culture a monolith today reminds me of Willy Wonka’s project of trying to create a chewing gum that would taste like a complete turkey dinner. No thanks!

Until Michael posted this…I had no idea that this list was out. And I don’t see the rankings being debated or taken apart anywhere. Just goes to show the impact Rolling Stone has on society these days and how far its fallen from the public conscious as a major player.

This list got lost in the shuffle…peoples true thoughts and feelings on this are pretty much fixed and have been for some time. The only discussion I’ve seen online about it is people mocking and disregarding it

And we all know in a few years they’ll just come out with another one to reflect whatever is going on at the time. Maybe the Beatles work will be higher…or lower. Or right around where it is.

And yes…what does it even mean “best songs” with so many different genres and eras mixed in with each other. Makes it feel rushed and poorly thought through

I think the 500 greatests lists were probably a over correction on criticism they got the first time around. Mainly lack of representation of female artists, black artists, contemporary artists and contemporary music genres like hip hop and rap.

I think it’s natural for the lists to change because I do think tastes in music change and music is a fluid thing. I also think that someone like Eminem for instance should be lauded as a great lyrical writer for his field of music as much as your traditional greats like Dylan Lennon McCartney etc. I also tend to agree that the first iteration was not very inclusive.

But yeah I think there was a definite overcorrection. I also agree with Nancy that it’s probably better to break it down by genre rather then having a one for all. I also agree with something Michelle said that does what constitutes “best song” or “best album” always the songs or albums you have the most fun listening too or sing along too? Like I love singing along to Respect but is it a better song technically and lyrically then Like a Rolling Stone which I have less fun listening too?

I’d point out though that the lists weren’t solely picked by the Rolling stone editors but voted on by a council of artists, music and entertainment insiders and they opened it up from my understanding to a lot of younger artists like Jay Z Taylor Swift Beyoncé Billie Elish etc. Basically everyone puts in their top fifty list and then I guess they rank based on how many songs/albums get the most votes ???

I do think the shift in Beatles songs/albums is interesting. Like I get that I want to hold your hand was ground breaking both from a music technicality perspective and in launching the Beatles to the world but it just seems strange to me that song is suddenly ranked in top twenty greatest song when there are songs from the Beatles catalogue that are stronger lyrically and musically and are more ground breaking.

I mean I think a song like Tomorrow Never Knows which I don’t think has ever made any best song list, was both innovative and groundbreaking as well as being a good track to listen to with good lyrics.

Or if we are going on just what people like listening too I believe Come Together Something and Here comes the sun are considered the most streamed Beatles songs on the internet and I’m pretty sure they didn’t even make the list this time around.

But I do think it’s part of a shift in thinking that the Beatles are the be all and end all of music, which to be honest I have never got the impression that any of the Beatles ever pushed that narrative themselves. It was IMO rock critics like Rolling Stone mag that pushed that narrative.

That being said, without being morbid, when Ringo and Paul leave us I’m pretty damn sure that the outpouring of grief and the talk of their legacy and their impact and influence on other artists legacies will outweigh any silly lists.

Well stated.

I did note (maybe I didn’t highlight it in the post) that the list was the editors plus critics plus music industry people, plus artists/performers. But I’ll say that here in the comedy business, people who make/package/sell comedy have a very different relationship to material than the audience does. What I like or admire or feel is groundbreaking or influential is not necessarily what is popular. The writer I would say utterly shaped modern comedy — and in a roundabout way provided the internet with a lot of its distinctive voice — is not one anybody reading this post has read for years. (Except for you, @Hologram Sam.)

This “priesthood bias” is one distortion; also age. Recency is hugely magnified in any business where being under 30 is so much a determiner of success. Taylor Swift (whom I know NOTHING about) would have to be kind of a freak to be really into Thelonious Monk; she’s likely into stuff that’s adjacent to what she creates. And that’s completely cool.

But these two biases mean that a list compiled by music editors, critics, and performers is going to reflect the tastes of now, because if you really dig Big Bill Broonzy (or even The Beatles), you’re not likely to become a really successful contemporary music editor, critic or performer. You can give the old people their due — that’s why this list has stuff like “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” on it, songs any idiot knows are important — but you’re not going to have much if any historical understanding of it.

Should you? Should “history” have anything to do with pop music? The old Rolling Stone said emphatically yes; that was what made the old Rolling Stone successful. So a Rolling Stone list where “Hey Ya” — a really catchy, successful pop hit — is five spots higher than “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” — a song that arguably remade the entire American music business — is notable. Personally, I like “Hey Ya”; but I don’t think it’s more notable than, say, “I’m Sexy and I Know It,” and if a critic has to explain to me why, then we’re talking about a priesthood spreading a certain dogma. Which is OK.

It’s funny you mention “Hey ya” I don’t know if any of you guys are active on Twitter but a couple months back there was a tweet that went viral where I think someone tweeted something along the lines that Hey Ya was a better song then anything the Beatles had written- which OutKast then retweeted.

This obviously generated a lot of discussion and most of it seemed to favour the OutKast opinion which I found a little bizzare.

There was talk about how Beatles got successful off the back of appropriating Black Musicians which is a fair comment- though I don’t think they stayed successful because of that. After their first couple of albums they moved on from strictly RnB songs and where more innovating there own music.

There was also a lot of commentary about how OutKast could have made songs like Yesterday, Hey Jude, Come Together etc but the Beatles couldn’t have written Hey Ya or Ms Jackson or other OutKast. Which while being an apples and oranges comparison also ignores the fact that something I think people forget is that it was just about music and lyrics but the fact that the Beatles created actual recording techniques that artists and producers use today that without them messing around in the studio or with out the producers trying to meet John’s demands to sound like a monk or smell a circus wouldn’t exist.

Then there’s the fact that just on sales figures and longevity no band has really able to maintain the dominance that the Beatles have after fifty years and only being a touring band for 3 years and a actual band for 8 years. The only band I think probably comes close is maybe ABBA. Or possibly Queen.

But Hey Ya is a good song. Lol

I’m not sure that I’ve ever heard Hey Ya. Probably, since it’s such a groundbreaking megahit. I don’t care enough to look it up and find out. Poor fools can’t tell the difference between musical influence and musical theft. Oh sure, OutKast could have written Yesterday, Hey Jude and mojo filter and spinal cracker. Well, maybe cracker would turn up in a lyric somewhere. Do OutKast and his Twitter followers not know that the Beatles toured with Little Richard, who didn’t begrudge them their admiration of black music, or that they were the first (only?) musicians to refuse to play to a segregated audience in the South? I wish modern black artists would drop the resentment and “appropriate” the magnanimous attitude that black artists of the ’50s and ’60s showed. Or better yet, use some of that music themselves. The Beatles got successful off their backs, eh? No unique qualities to their songs whatsoever? We’ve been listening to the Supremes all this time?

I think the African American Musicians of the fifties had respect for the Beatles because the Beatles showed and paid their respect for them and would usually turn into fan girls in their presence. Also a lot of African American artists covered Beatles songs- there’s an awesome playlist on Apple with some of them.

What I think is a genuinely curious question and not something I’ve seen explored much is were the Beatles as well received with African American audiences during their hey day as they were white audiences? That’s actually something I’m curious about.

I mean Motown was massive in that same era – so much so it became it’s own genre. Which was dominated by African American artists. But I think it’s a curious question about if those same audiences embraced Beatle mania

That the Beatles appropriated black musicians underlies a misconception about rock and roll, I think. While the Beatles hailed the influence of black artists, and rightly so, the genre was a melding together of African rhythms and Anglo/Celtic folk songs and ballads that accompanied the first settlers into America and fashioned into its own country music (also evident in the Anglo/Celtic environment in which the Beatles grew up). I may be wrong, but I believe that without either element, rock and roll would not exist. But notably, black musicians developed the form which gave them a voice. As far as Outkast go – the assertion that they could write songs like Yesterday, Hey Jude, Come Together, Strawberry Fields, etc. , well, why haven’t they? It reminds me of Elvis Costello, when collaborating with Paul, stating that he thought it would be easy to write a song like Hey Jude, then having to back down and admit that he couldn’t. The chord structure and progressions had him stumped. On the other hand, I also recall a radio interview with Giles Martin, where he was explaining to the interviewer, the layers and overdubs to Lady Madonna, recorded in 1968. He went on to demonstrate them by peeling them off one by one. When Martin reached the bottom layer, what did we hear? Hip hop.

I think it’s great that Black musicians and singers are being more publicly credited with initiating rock and roll than in decades past: the genre is unimaginable without the work of Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Fats Domino, the Supremes, and on and on. It’s fair to say that just about every rock musician of the 60’s and 70s drew heavily on the Black tradition, often without enough acknowledgement. But to my mind there’s an important distinction between artists who adopted musical styles virtually wholesale (say, Eric Clapton’s cover of “I Shot the Sheriff”) and artists who put their own spin on it (say, the Beatles’ “You Won’t See Me”).

I wanted to add a reference to the kind of “best of” list I DO find useful. I have this edition of the Rough Guide Book of Playlists, and recommend any version of this book highly. (They’re all out of print now, but readily available used). It includes lists devoted to artists and to genres, and lists picked by musicians. The Beatles get three lists — one overall “best of,” as well as lists of songs primarily written/sung by John and those primarily written/sung by Paul.

And there’s a list for Outkast, unsurprisingly topped by “Hey Ya.” I especially appreciate the unusual playlists — Billy Bragg’s list of “Busking Tunes,” and the lists for “Brilliant Covers” and “Olympian Vocals,” to name a few. I find these lists informative and useful, unlike the “Rolling Stone” megalist.

Well said, @Lara. Agree 100%.

There’s another aspect to the “stew” that made rock and roll, and it was the essential one: the reaction of audiences. and to me this is where things get interesting, especially in the case of Elvis Presley and, to a lesser extent, The Beatles. Those two were successful on a commercial scale that no Black artist had been, and would not be until Michael Jackson. All three of these acts are what the industry calls “crossover,” and only a handful of people/groups have been able to create that kind of mass popularity across racial boundaries in a durable way.

In the case of Presley, I think you can argue that he was adding the least, and that much of his early success is being a white man doing quintessentially Black music, in a quintessentially Black way, with the approval of an explicitly racist album and radio business. I wasn’t a teenager in 1956, but I hear not much translation on the part of Presley. Presley fans might hear it differently — but I would much rather listen to, say, Ray Charles’ ’50s work. To me, Elvis always feels like “all the things you like about R&B and Gospel, but…less.”

With The Beatles, their covers of songs by Black artists show that they are firmly “Beatlizing” them; and that is a point in their favor. Furthermore, these R&B covers are firmly minor songs in the Beatles’ catalog, even entirely worthy numbers like “Twist and Shout.” They’re definitely not the same thing as the Stones charting with wan versions of Chicago blues with English accents. The songs we remember The Beatles for, even from their earliest days, are original compositions with no immediate aural antecedents in Black popular music. “She Loves You,” “I Wanna Hold Your Hand,” “Help!”, “Day Tripper”–these are fully new things, with the influences digested–so much so that Black artists could reverse the usual process and produce great covers (I’m thinking of Wilson Pickett’s “Day Tripper“, and EWF’s “Got to Get You Into My Life,” but there are many, even in the jazz genre).

The Beatles took from Black R&B, Anglo/Celtic folk songs, country, rockabilly, etc and created something powerfully new…which is revealed by a mass audience reacting to it in a powerfully new way. No Black artists were reaching the heights of The Beatles in 1963-64; Motown as an aggregate came close, but that’s not quite a fair comparison. So I get a little weary of Rock critic know-nothings who lump The Beatles in with other white acts (Elvis, Stones, Led Zep, Clapton and ilk) that were straight re-appropriation of Black culture for a white audience. It’s shoehorning them into an often-valid criticism of rock and roll, in order to diminish them, and I got a whiff of that from this list.

Another interesting case is Michael Jackson, who did it from the other direction — a Black artist who was able to crossover, through consummate skill and a winning brand. Prince did this too, to a lesser degree, and Stevie Wonder. Like The Beatles, these guys are unquestionably musical geniuses, and restricting them to this or that racial category, even in service of fairness, always strikes me as a diminishment of art in favor of politics. Another interesting case is Earth, Wind and Fire, who explicitly wanted to cross over, and did for a short time (I’d say from 1976-80, on the back of disco), but could not sustain that popularity.

I think it’s only honest to acknowledge the profound handicaps faced by Black artists, even in the arena of popular music, one of the few areas that racist white culture allowed them any success at all. But when we’re speaking of The Beatles in the 60s, we’re talking about an extended cultural happening orders of magnitude greater than, say, Fats Domino, Little Richard, or Chuck Berry. Or, God love her, the divine Aretha Franklin.

@lara Very good point! I watched a really good three part documentary on Lennon and McCartney lyrics and music which went into each period of their music including their solo work with “Beatle experts” breaking them down- music critics, Beatle biographers etc.

One on the interviewees was a music professor I believe and he talked a lot about the fact that there songs were deceptively simple, in that they sound like easy melodies to listen to but when you try to break down the cords they are actually quite complex to play technically and that they use cords changes that aren’t typical. One example he brought up is Drive my car.

And on the hip hop thing, you could argue that Tomorrow Never Knows was the earliest commercial precursor to techno music and the use of sampling that is an essential component the rap/hip hop genre. Also the fact that the Beatles pioneered using the studio as an instrument which is very much the same ethos as rap/hip hop genre.

And honestly as far as the whole “OutKast could have written…” It’s easy to say that 50 years after the fact. But the question is will artists like OutKast or your big acts of today- Kanye, Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Adele- still have the same cultural relevancy they have now in fifty years that they can still be making the same amount of money and impact as they do right now.

I read a Forbes article a few years back about how the Beatles still generate something like around 70 million a year in royalties and merchandise sales. John Lennon Estate typically takes in like 15 -18 million a year alone and he’s not even alive to be earning.

I also read an article just recently about Juliens auction house which specialises in memorabilia sales and how they said there has been an increase in demand for Beatles memorabilia more then any other artists since Covid because they find that more people, including younger people, have been re-embracing the Beatles as comfort music to get them through tough times globally and politically.

I guess that really plays to @Michaels point about crossover appeal.

@Nancy good point about the fact that the Beatles usually would put there own stamp on a song and do it own way.

Feels like maybe there’s quite a bit of nuance missing in this discussion, especially around power dynamics in terms of the Beatles and the Black artists they took from, and some of the dismissal of OutKast’s talent and contribution to modern popular culture here in order to prop up the Beatles is…ironic to say the least. You don’t have to like his music, but he deserves a bit better than some of the comments here. A couple of other things that have really stuck out to me:

Michael, you mentioned that the straight R&B cover songs the Beatles did in their early career were not in the majority. It’s true but those are the ones – alongside the hundreds of others they never recorded – that influenced their sound as we know it which, in turn, gave them their absolutely enormous platform. It’s not just about the music they covered or were influenced by either. There are a thousand and one examples of this but for instance, I Saw Her Standing There’s bassline is Chuck Berry’s, wholesale. They didn’t make it their own, they stole a bassline and wrote a song around it. So, while white men with influence were calling the Beatles “genius” and “innovative” and writing Twilight of the Gods and giving John and Paul Ivor Novello awards, it’s probably not unreasonable to wonder if Black musicians might have been a little less enthused by the idea that they’d been writing songs on this stuff for years and no-one called them geniuses or gave them MBEs. So the animosity, or the idea that the Beatles got famous on the back of Black musicians, is directed at the Beatles, but also at a white mainstream critical and cultural audience who talked about the Beatles as if they were the first to create music that sounded like that. No matter how many times the Beatles gushed about how much they loved Little Richard or Chuck Berry or any other Black artist they enjoyed listening to, they weren’t paying them for the ideas and work that they took. That is an anachronistic concept in some ways, the idea of reparations and remuneration for culture stolen and appropriated is probably not one that existed in the Beatles’ world in the 60s. I imagine maybe it did for Black artists – the lack of acknowledgement in anything other than lip service may have been…frustrating.

LeighAnn, you mention their chord progressions. While Howard Goodall and Alan Pollack and plenty of others have waxed lyrical about the “strange” chord progressions, many of them – in particular those in John’s work – are found throughout Black artists’ music at the time. All the way up to Let It Be the Beatles are using doowop chord progressions and 12-bar blues. Lots of Beatles music is atonal, which is extremely unusual for pop music – or was at the time – but not in jazz music. If I Fell and In My Life both have a famous chord progression that takes the harmony from the major 4th to the parallel minor, something that became a bit of a Lennon speciality, and was much praised for being mature and melancholy and worldly, but it’s also a fairly standard tool in a blues musician’s tool box.

Like everything discussed on HD, I think it’s about taking the good and the bad and letting them coexist. The Beatles absolutely did steal from Black artists – call it homage or influence or whatever else, the ideas weren’t always their own but they were paid handsomely for them regardless. They also were in turn stolen from by their contemporaries, especially white British bands. That is a far more even transaction in terms of social and cultural capital, but must have been frustrating from time to time (Lennon certainly thought so in his early 70s interviews, even handed and generous though they were). They also did, as lots of people have mentioned, create a sound that was all their own by mixing other very different styles in with their initial influences as they matured. I don’t think we need to absolve them of theft – they did it, they knew it, and exploring that is a good thing. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock’n’Roll by Elijah Wald has a deliberately provocative title, it put me off through pure defensiveness for years but I decided that was a good reason to make myself read it, and it’s great. Basically about rocknroll’s relationship to jazz/blues/ragtime and plotting a more truthful and even-handed path between the two. I think this subject is one of the most difficult in Beatles discourse, but I also see it as filled with opportunities to make progress and tell the story a bit better.

@Nikki, WONDERFUL comment, thank you. I particularly liked your musical specifics. I want to state right from the beginning that I look at this as a creator in a same-but-different field, and not a musician, critic or theorist.

“you mentioned that the straight R&B cover songs the Beatles did in their early career were not in the majority.”

I said that they were “firmly minor songs in the Beatles’ catalog.” The Beatles’ covers are not why we’re still talking about The Beatles. Unlike Led Zeppelin, for example, or the Stones, or Clapton, none of whom could be imagined without Chicago electric blues. What makes The Beatles distinctive or extraordinary is not their versions of other people’s songs, white or Black, nor their work inside standard idioms. When The Beatles did straight blues or R&B or country, IMHO, they were diminished. (their attempts at rockabilly; “Act Naturally” and ilk; their Motown and Arthur Alexander covers; “12-Bar Original” from the Rubber Soul sessions; “Yer Blues”) Even when they did calypso, it’s minor work (that take of “I’m Looking Through You”; “Obladi Oblada). The Beatles only reach their heights when they’re making distinctively Beatles music, working in their own idiom.

“There are a thousand and one examples of this but for instance, I Saw Her Standing There’s bassline is Chuck Berry’s, wholesale. They didn’t make it their own, they stole a bassline and wrote a song around it.”

There are clearly NOT a thousand and one examples of The Beatles swiping stuff wholesale, because if there were, they’d have gotten sued — as George and John both were, successfully. In any creative art, and certainly in any popular/commercial one, everybody builds on someone else. That’s a different issue than groups with privilege having economic access and advantages that other groups do not. This is of course true and worth digging into; The Beatles benefitted from this to same degree (whiteness, handsomeness, non-disabled, English-speaking) and were unfairly hindered to some degree as well (Englishness, antiauthority stance, femme notes in their appearance). But they clearly weren’t stealing stuff to any uncommon degree because if they had, all the white-owned record corporations and music publishers would’ve sued the hell out of them. As Morris Levy did with “Come Together,” and Allen Klein did with “My Sweet Lord.” We don’t have to guess at the level of larceny; it was low. Most fell within the boundaries of their time and business.

“also at a white mainstream critical and cultural audience who talked about the Beatles as if they were the first to create music that sounded like that”

The whole point of The Beatles is that there hadn’t been music that sounded like that. Nobody else, white or black, had made that sound — nobody had combined those influences in that way. We might surmise that if, say, Ray Charles had looked like Pat Boone he would’ve been a huge crossover guy (more than he was), but none of The Beatles’ influences sound like The Beatles; and The Beatles in turn spawned a million imitators, which also suggests that their mixture was unique. I’m not disputing how Black artists were shafted; but you can say that without claiming that something that commerce and galvanic audience reaction identified as unique, was a copy. It wasn’t a copy. And it couldn’t be copied; people tried with The Monkees. People have been trying ever since.

“Little Richard or Chuck Berry or any other Black artist they enjoyed listening to, they weren’t paying them for the ideas and work that they took”

…but they were, when they recorded their songs, or took sufficient amounts of unique IP that a court ruled. The idea that artists should pay their influences is a pleasing one (I have influenced a lot of people by now!), but it’s impossible. How much should Chuck get for that bassline? And are we sure he didn’t steal it from some other person, some guy he saw in a club in St. Louis in 1947? Maybe even…a white guy? In the moment, influence is hard to ascertain. And influence is fundamentally unruly. It’s only in the mind of the critic that it is so distinct.

“strange” chord progressions, many of them – in particular those in John’s work – are found throughout Black artists’ music at the time”

Fascinating!

“doowop chord progressions and 12-bar blues”

This makes me think: who invented the 12-bar blues? Do we know? Could we ever?

“Lots of Beatles music is atonal, which is extremely unusual for pop music – or was at the time – but not in jazz music.”

The Beatles were adamant (with the possible exception of Paul) in their dislike of jazz music, and no portion of their pre-64 biography has them absorbing much jazz. And none of them were formally trained in the least; so could it not be a case of coming up with something that already existed? Is that not also possible? I completely buy the Fabs’ intentionally quoting 50’s rock and R&B, but something as theory-based and virtuosic as jazz? I’m dubious.

“the ideas weren’t always their own but they were paid handsomely for them regardless”

As someone who does popular art, @Nikki, no artist can survive this test. We all spend years and years consuming the art we love, then attempt to increase our pleasure by making it ourselves. (It’s never as good, but that’s another post.) Especially if you’re not formally trained, learning by imitation is prone to quoting, and I can go through anything I’ve ever written and say, “Here I’m doing Doug Kenney” or “Robert Benchley” or “Monty Python.” Who, in turn, had their own signature stew of homage and ripoff and revision and yes, a bit of new stuff. Popular art hews away from really new stuff because large audiences are less likely to appreciate or understand it. Someone who can put across something truly new is rare indeed. And even so…I’m not sure anything is new. Not in truly popular arts. Because people aren’t new.

To be honest, I think the language of “theft” and suchlike is not helpful, and that’s not just my own Anxiety of Influence talking. “Theft” rather than “influence” assigns malign intent when often there is none, and intentionality where there often is none. It suggests that unfairly privileged creators are looking to steal, ruthlessly, from the underprivileged/underrepresented because they can, and lack any intellectual integrity, and sometimes that’s true, but after 35 years doing a popular art, in my experience it’s rare. A topflight creator in an art can do what I did above — “Kenney…Benchley…me…That’s a Jones/Palin approach, but set in my life…me…Perelman” — and The Beatles did that. Imitation is a method of creation, just as improvisation is a method. Theft is…theft. Given the litigious nature of our society — there’s big money in protecting copyright — I don’t think it’s fair for us to be MORE harsh than the lawyers. If the argument is corporations stole stuff, I can buy that; the horrible contracts and publishing agreements leveraging corporate power against the individual creator. But fellow creators? In my experience, mostly not, for lots of reasons. I could be wrong; music could be different, The Beatles could be huge thieves, but…wouldn’t some lawyer take that case, over the last 50 years?

What this issue is really about, of course, is systemic racism, and that’s an ongoing holocaust. Systemic racism has seeped into our economics and culture — one could say it IS much of our economics and culture — and that can and should be admitted and rooted out. But to point to The Beatles using 12-bar blues progressions as proof that they were thieves…that seems as unfair as saying Ray Charles used ’em, and gets into discussions of weird racial purity. Is comedy, then, a Jewish art form? Should Richard Pryor have to pay Lenny Bruce, much less the millions of vaudeville guys who made standup into what it was in 1964 when Richard started? Like comedy, rock has a million fathers and mothers, and who gets paid for what is always mediated by a million external factors, many of them unfair, and many of them bullshit. When ownership can be ascertained, and the amount of IP taking is above and beyond the standard within the music business, the lawyers usually come out. Who owns an art, and how to pay/value artists — this is always unfair; even The Beatles haven’t made as much money as Jeff Bezos. Artists always get fucked; and it’s precisely because of this I think The Beatles are an example of the good guys winning — artists making things and getting paid — rather than another example of white artists ripping off Black ones. There’s plenty of that, but The Beatles are neither prime offenders nor valued because of their borrowings. But I am certainly willing to be convinced otherwise.

Am I the only one who thinks that a lot of the Beach Boys music, especially their early stuff, sounds like a ripoff of Chuck Berry?

McCartney threw some shade at the Rolling Stones recently when asked who was better, them or the Fabs. He said the Beatles were influenced and utilized all sorts of different styles of music, but with the Stones it was just the blues. I don’t agree with that. I hear a lot of country & western in their music as well (and not just Wild Horses).

Literally just came across this site for the first time, this is the first post I’ve read on it, but I felt compelled to reply:

“[x] could write ‘Hey Jude’ but the Beatles couldn’t write [y]” (or, relatedly, “[x] is better than anything by the Beatles”) is a pretty common meme frequently used in a joking fashion (although in this case I would say there’s at least a twinge of sincerity); you’ll see similar posts subbing in other widely exalted greats like Scorsese or Shakespeare for different types of media. Generally it isn’t something I would take very seriously, and after going back through OutKast’s Twitter feed (which is definitely not run by either André 3000 or Big Boi) to see the original tweet (see here: https://twitter.com/RonFunches/status/1378754235404185601), based on the second tweet in the thread, it’s pretty clear that what was initially said wanted to spark controversy to promote the guy’s show.

To expand beyond that point, however, I think Nikki’s post touches on a lot of younger people’s frustrations with (the exaltation of) the Beatles. There are much greater cultural power dynamics going on than just “they were inspired by Black artists,” and people are responding to the continued disenfranchisement and downplaying of Black musicians at least as much as they are to the Beatles’ legacy. You also can’t act like they put their days of being largely influenced by or outright stealing from Black artists behind them as they grew further in their career/s—”Come Together” and “My Sweet Lord” provide pretty clear examples that prove that’s not the case.

I would also add that beyond the inherent racial dynamics, I think it is also just related to the frustrations young people feel towards Baby Boomers and Boomer cultural institutions in general. So many people feel like Boomers have written away their future; why should they care about some old band singing “All you need is love” when faced with environmental crises, terrible healthcare, police brutality, and growing economic inequality? Killing a sacred cow like the Beatles like this is a way of letting out some of that tension. As you point out in another comment, though, plenty of young people of all kinds of backgrounds do indeed still love the Beatles and take inspiration from them. To provide some recent hip hop-specific examples given the discussion: Drake sampled “Michelle” on his song “Champagne Poetry” (through a sample of another song that sampled it, “Navajo” by Masego), “Black Beatles” by Rae Sremmurd was a huge phenomenon that Paul even acknowledged, Frank Ocean interpolated “Here, There, and Everywhere” on “White Ferrari,” and, of course, Paul did “FourFiveSeconds” with Rihanna and Kanye West.

To close things out, I would agree with Nikki’s assertion that there’s a dismissal of the impact OutKast, and Black and other contemporary artists in general, have had on popular music (although I must clarify that OutKast is two men, though “Hey Ya!” was functionally an André 3000 solo song). Sure, I don’t think any of the artists mentioned have completely changed the face of music and culture as a whole and maintain such widespread cultural relevancy like the Beatles, but I don’t think that’s possible in this day and age; media is too fragmented, and I don’t know if there’s even the space for making half as many studio innovations as the Beatles did. But it’s not like the only rock musicians we remember from the ’60s are the Beatles and the Velvet Underground. The other artists you mentioned in a reply are immensely talented, and I can guarantee that at the very least Kanye and Beyoncé will be talked about for the ways they pushed their respective genres and created multiple monumental, conversation-shifting albums.

And OutKast? Before OutKast, hip hop was largely relegated to the east and west coasts. OutKast demanded the country pay attention to southern hip hop, which has since dominated not only rap, but popular music in general the last two decades. Both lyrically and musically they tackled a wide range of topics and musical genres with some of the best lyricism in hip hop ever. And beyond that, “Hey Ya!” is a perfect pop song. Who cares if it didn’t pioneer a whole new genre? Perfect is more than enough.

LAW, good points — thanks for commenting! Resentment of Baby Boomer culture and “received wisdom” plays a big role in some younger people being fed up with the older bands that are typically lionized, including the Beatles. I get that, although I’m Gen X and don’t feel it as strongly as younger generations probably do.

And I absolutely have no wish to diss OutKast or any other artist/group. I just think it’s crazy to compare songs across decades and genres as this RS list is trying to do and declare “winners.” I can’t see how it helps anyone.

Great reply, @LAW. Here are some thoughts based on your thoughts. Not disagreeing, just thinking out loud, and my opinions on these kinds of things shift like the wind:

1) ” is a pretty common meme frequently used in a joking fashion”

This is one of the biggest problems with post-internet, and especially post-social media, discourse. Vast proportions of discourse use “in group” coding — for laughs and speed — but that content is encountered by everyone, not just members of the in group. And so you get a ton of misinterpretation. If I write, “Yeah, the Beatles totally SUCK” that’s a statement that decodes very differently in this comment on this site by me. Social media is a system designed to commodify attention, not spread accurate understanding, and the irony-heavy, constantly shifting argots that users are trained in are platform-specific (Facebook-speech is different than Twitter-speech, which is different than TikTok or IG) and even different within subgroups of users. This is an amazingly heavy decoding load and that, combined with the decay in reading comprehension caused by the shift from the word to the image, has created a vast wilderness of confusion, alienation, and misunderstanding breeding tribalism and hostility. (Which is the opposite of what people like me thought the internet would bring, back in the mid-90s. I find that interesting.)

2) “think Nikki’s post touches on a lot of younger people’s frustrations with (the exaltation of) the Beatles”

Younger like 15? Or 40? Anyway, as a Gen Xer, I feel you; my generation’s cultural existence has been totally overwhelmed by the demographic power of the Boomers, and now the digital omnipresence of the millennials. In my business, comedy, my career has been irreparably harmed by the refusal of Boomers like Lorne to fucking retire already. But all that having been said, anybody seriously analyzing certain popular arts–comedy, movies, music–has to admit that there are high points and genius practitioners; generational politics are not the only thing at play. And there are eras where more good work is produced, and fallow ones, as well. The Beatles (who were not Boomers) benefitted from lots of demographic/economic/technological factors, and other bits of timing, and I talk about all those things a lot here. But fifty years on, I think we can say that their position in the culture — their historical prominence — is earned. They’re not Vanilla Fudge or, dare I say, Led Zep, or Eric Clapton. To look at The Beatles and flatten them into yet another Boomer totem is to fundamentally misunderstand who and what they were, and elide a period of history that is absolutely imperative to understand if we’re going to survive, much less make a better world. And to do that for generational reasons is, to me, foolish. Having generational frustrations drive the discourse is like me saying, “Why don’t people talk about Squeeze or XTC?” And shit, why DON’T they? Great bands, really popular, really influential, made some perfect pop songs. But they’re not historically important, and to say that they must be, because they mean a lot to me personally — once again, that’s turning history into one’s own comfort animal. Which we all do, and is OK except that it doesn’t teach you anything. I was born in 1969; liking The Beatles is a STRETCH for me, but it’s one I’m willing to make, and glad I’ve made, and trains me for other stretches (including OutKast).

3) “people are responding to the continued disenfranchisement and downplaying of Black musicians”

There are lots of distinct issues here for me. First, there’s a suggestion that the culture (who? fans? corporations?) treats Black musicians today in the same ways it treated Black musicians in the past and…that’s a big statement. I can’t speak to it, I’m not a Black musician, but it would seem like things are certainly better in this regard than they were in 1920 or 40 or 60 or 80? Black citizens deal with innumerable systemic horrors, but are Black musicians being disenfranchised by the music business? Or is this just something we can discuss because white Americans like myself won’t discuss the systemic horrors? Second, we live in a culture that does not value musicians of any color, or artists of any type, so once again, complicated. Is there racism? Yes, tons. Is there also capitalism? Yes, tons. Is it the same as it was? No. Is it fixed, or good or fair or right? Also, no. But third, downgrading The Beatles or any other act doesn’t help Black musicians, or musicians, today. It’s simply a posture, a pose. There’s a peculiar bit of magical thinking common on the internet that says if we express the right opinions using the right language, systemic/structural problems will be solved. But that’s not true, and it’s growing less true with every Republican gerrymander. If there’s one thing that studying the Sixties demonstrates without any doubt, it’s that cultural dominance is no substitute for political change, and the totemic aspects of this new list are profoundly depressing. White America still hasn’t fixed what Sam Cooke is singing about, or Billie Holliday — the songs still “hit”, unlike Stephen Foster or ragtime– and that’s appalling. If I were a POC, I don’t think I could live in this society; “frustration” wouldn’t even begin to encompass it, and I suspect it doesn’t really encompass the feelings you’re reporting in that phrase.

“that there’s a dismissal of the impact OutKast, and Black and other contemporary artists in general, have had on popular music”

I will absolutely cop to being skeptical about anything contemporary, especially in popular culture, because of the billions behind promotion. But my gut skepticism aside, what even IS popular music today? Who is it for, and how is its impact measured? Should recency have anything to do with it? Is “Hey Ya!” more important, more influential, better than “Rhapsody in Blue”? How about all the other standards that so often were written by Jewish songpluggers, had one life, and then were given new life by Black jazz musicians? Those musicians counted; those sales counted; and if you’re going to attempt the impossible task of “500 Best Songs,” you can’t just punt on everything pre-1955 because black and white movies bore you. A “500 Best Songs” list is an inescapably, inherently historical task, and there’s nothing that bugs me more than presentism, the means by which our society keeps us children. To my mind, this list massively overvalues contemporary artists…and just happens to put “Respect” at #1 just in time for an Aretha biopic, so its basic good faith should be questioned. If it’s a branding exercise for the Rolling Stone reboot, fine. But if we’re talking fairness, there are a lot of artists that were completely ignored by this list — artists who were massively popular in their era, who wrote and performed songs that were standards in American and Western pop culture for fifty years or more. Rolling Stone has a right to gather whomever it wants, to make whatever list it wants, but there’s a lot of questionable submerged judgment here about who and what is valuable and valid and what is not, and I think that’s worth pointing out. I picked “Hey Ya!” because I know and like the song, but there is an appalling recency bias all throughout this list, and that’s my beef, not the relative merits of OutKast.

Again, great comment! So much to think about, and you’re making me think about this stuff more deeply. Appreciated.

“There’s a peculiar bit of magical thinking common on the internet that says if we express the right opinions using the right language, systemic/structural problems will be solved.”

Ooooof. That is so, so true.

Personally, I think polls such as these are redundant in this age when there’s such overwhelming musical choice spanning across all genres (including genres that most folk will never have been aware existed). Believe me – I know – there are literally tens upon tens of dozens of new albums released on a weekly basis outside of the mainstream and almost as many new singles but because they do not and will not ever reach that widespread mainstream attention, they will not be noticed by the likes of ‘Rolling Stone.’ So, with that way of figuring, basically, if something ain’t been in the Top 30, it’s not acknowledged or known to have even existed . So, does that mean it’s not ‘one of the greatest’? Well, I would argue, ‘no,’ it’s not. And there’s one of the rubs; Polls such as this are redundant.

Excellent piece Michael. Well argued.

Your question of what RS is today reminds me of that identiy question that both Heraclitis and Plato bandied about in years past. We know it as the Ship of Theseus paradox. If all the constituent elements are replaced over time is it fundamentally the same object?

You make a good case that RS certainly no longer seems to be.

Neal, your comment about the Ship of Theseus reminds me of the old story about a family that claimed to have George Washington’s ax. “It had been passed down through many generations and was the original ax, although they’d had to replace the head twice and the handle three times.”

I’ve always believed that creative people create things and non-creative people make lists.

I agree with everyone here about the futility of rating songs from different genres. “Which is better? Stardust or Whipping Post?” It’s just silly.

Why not a “best of” list of animals?

Cat

Capybara

Giraffe

Dolphin

Turtle

Neurotics build castles in the air. Psychotics live in them. Magazines rate them.

Hey, dogs are CLEARLY the best animals! (I’m ALMOST not kidding :0)

Let’s see what Mark Twain had to say: “If man could be crossed with the cat, it would improve man but deteriorate the cat.”

I have a really hard time finding any way to dispute that!

Thank you, @Neal.

Important magazines (like important rock graups) create and are created by, a specific era. When the era is over, the magazine has to forge a different relationship with a new time, and most can’t. Lightning does not strike in the same place twice (except when it does).

Today’s Rolling Stone could be just as well written, brilliantly designed, and edited with as much panache as it was from 1967-80, and it wouldn’t occupy anything like the same cultural heft it once did. Similarly a band as talented as The Beatles could come along and there’s no guarantee that they would be as successful or influential or lauded. The music business is very different; music is consumed differently; the Fabs’ secrets would be all over social media within hours of their being on Ed Sullivan; and there’s no Ed Sullivan, either. This blog has increasingly become about the Beatles era because that was as much a part of the story as John, Paul, George, Ringo, etc.

Magazines are simply not the shapers of culture that they once were; nor is “culture” shapeable by any single institution. Whatever the culture is, seems to be shaped obliquely by the decisions of the big tech companies, whose platforms and algorithms favor certain things and hamper others. The gatekeepers still exist, they are just much more hidden; it used to be Jann Wenner slamming RAM. Now it is Facebook allowing celebrities to post without moderation.

@Nikki, I’m sorry but I think you have misinterpreted what I said. I did not imply that Outkast was not talented or that hip hop is not complex. Far from it. It was the assertions of Outkast’s fans to which I directed my comments, and I stand by them – that the Beatles could interpret and innovate from many diverse musical sources and it is that which made them so exceptional. I also said that rock and roll was the melding together of two elements: African rhythms and Anglo/Celtic folk ballads. No music exists in a vacuum. Jazz itself borrowed heavily from classical music. Classical composers borrowed from each other all the time; indeed it was considered an honor. Of course the Beatles nicked – all artists do. The difference being that the Beatles acknowledged their sources. Paul clearly stated from the beginning that he had taken Chuck Berry’s bass line for I Saw Her Standing There because it suited their song nicely. Berry was happy with that. The topic of plagiarism is interesting in itself. The reason we see fewer cases in court today is because the plaintiff has to prove beyond doubt that they did not in fact steal or borrow from something earlier themselves. The number of notes and chords in musical language is limited: it’s how they’re put together that counts. And in doing so, the Beatles changed the way popular music worked and it had little to do with the color of their skin.

I think McCartney’s assertion about the Stones is reasonable enough. If we are comparing the two bands output for the years up until 1969, the Stones were largely blues influenced. Most of their country songs were written from 1970 onwards.

Is it just me or since perhaps the late 90s or so all of society has become list obsessed. It’s a form of clickbait everywhere…intended to stir up arguments, conversations, debate. And in the social media world everyone is posting “Top 10 this, top 100 that” and it changes so rapidly, yearly…these rankings list of everything from greatest football teams to best bands to top songs seem completely worthless.

It used to be that we’d have a few authorities on things, and every so often experts would gather and discuss…few lists would come out and that stir up water cooler discussion across America for a while. But now everyone is churning out so much of this nonsense that I find it rather hollow and worthless.

Back in 98/99 when MTV or VH1 aired a program of the best bands…best songs, best music videos it held some weight and got people talking. And it had staying power.

Now there are dozens if not hundreds of publications churning these out daily.

Dave, heartily agree. “Listsicles” (“articles” built around lists) have a good record of getting people to click on them, so there’s been an explosion of lists of anything and everything in the past few years. Seven ways to lose belly fat, Six signs your girlfriend/boyfriend is cheating on you, Five photos of celebrities without makeup (you won’t believe #3!), and a partridge in a pear tree.

And since music, movies, video games, and TV shows are such a huge part of fan culture, they’re especially ripe for this kind of list making. And as you say, it’s about stirring up engagement — in the service of more clicks. It’s also why when a musician gives an interview or writes a memoir the nugget that gets widely publicized is often some kind of knock on another musician or group. It’s all pretty shallow and tiresome.

It doesn’t surprise me at all that this RS list doesn’t seem to be getting much cultural traction. It certainly doesn’t deserve any, in my opinion.

It was the sheer universality of the Beatles music that took them to the far corners of the world. Precisely for being genre-bound and for other reasons already discussed, we are not seeing the same phenomenon with current artists, regardless of how talented or relevant they may be. Will OutKast, Beyonce, Kanye be discussed in 50 years time? Will the Beatles? We don’t know because America/Europe may not even be the dominant culture by then. Australasia, Pacifica? India, China? Maybe or maybe not, but I think the heyday of American popular culture has dwindled as more and more countries invest in their home-grown talent, not just in music, and look less and less towards America for success. Nikki, I feel it is a little unfair the idea that white men only write about white mens’ music. Any trip to the stacks of any local library will show rows and rows of books on jazz, blues, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll, many of them written by scholars irrespective of race exhorting the genius of Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Dizzie Gillespie, James Brown and many, many more.

As an aside, I can’t help but be mildly amused by the culture that loves lists is also the culture that loves to label its generations. As a member of the boomer generation, quite possibly the most scapegoated generation in history, I find the term patronizing, a label we didn’t ask for and thrust upon us by marketing gurus desperate for our poorly earned cash. Rest assured, postwar generations in other cultures, particularly Britain and Europe, did not have the same experiences as those growing up in America, nor did women and minorities of the generation anywhere have the economic and social advantages taken for granted today. And compared to white, middle-class males, they still don’t. Because this group has always had it good, still does now, and likely to continue to for some time. Any frustration felt towards males over a certain age is easy to explain – there are simply more of them. Which also leads to the oft-noted confusion over when the generation actually began and ended (purely because of the invention of the contraceptive pill) – do people seriously believe the social, economic, and cultural society kids were born into in 1960 was the same for those born in 1946?

@Lara, so much good here.

Looking at the popularity of the Beatles via the lens of colonialism — that popularity in Britain gave them an advantage in the decolonizing-but-still-culturally-connected portions of the British Empire. Topping the charts in Britain gave them a leg up in Canada/Australia/NZ/Hong Kong, and also India and America. But it’s also interesting that there was no worldwide British musical or cultural phenomenon in an earlier time, when mass media still existed but the Empire was still intact. Mass culture in the 20s and 30s — when I’d argue that Beatle-like fame was invented — wasn’t British, but American, coming from Hollywood specifically. Would Charlie Chaplin, the Beatles of 1915-30, have become the worldwide phenomenon he was, if he’d stayed in the UK? Was the leg up in the Empire strong enough? Clearly he didn’t think so, which is why he decamped to Los Angeles at the first opportunity.

So I would say that rather than the Beatles’ Britishness and access to the territories of Empire being the determinant of scale, I think it was the Cold War dipolar world. The Beatles were a phenomenon of the Western alliance — Japan, but not China; France and Spain and Italy seemingly less than Germany. If you were fully behind, and being subsidized by, the American-led capitalist project, the Beatles were massive; if you were conflicted, as DeGaullist France was, The Beatles were still popular but not as much (1964 Paris concerts).

The Beatles are historical in scale; they are inextricably linked to the world’s geopolitical story from 1945-89, and this is why I’m confident they’ll be spoken of, whatever forms popular music takes. The Beatles were wonderfully talented, miraculously talented, but they were also perfectly positioned — even more than their contemporaries in rock — to stand in for Western culture as a whole at a time when culture was a tertiary choice (US/Soviet/China). The Beatles were seen as, and used as, Western propaganda; and just as the CIA was funding American literary journals and modern art, rock music as a form and Beatle music in particular was viewed as a pro-Western, pro-capitalist statement. That’s in part why the Beatles’ working class background was so much a part of their early story in the media. They are a powerful advertisement for capitalism…in a way that screwed-over Black artists were not, and could never be.

If you work in culture (and maybe you do), the first misconception to die is “success is proportional to talent.” The second, perhaps, is that “omnipresence is importance.” The Beatles were hugely talented, but that doesn’t explain the hugeness of their success. And they were omnipresent during the Sixties, but that can be purchased. It’s only time that can allow these things to come into focus, and I think it’s the persistence of The Beatles for 59 years and counting that is the best indicator of their relative talent and importance. Aretha Franklin is a wonderful, wonderful artist, but she is located in the American Black Gospel tradition, and the Sixties. That’s part of what makes her wonderful, but it’s likely to make her fade. Ditto Frank Sinatra, Nirvana, etc. The Beatles seem to be transcending time and their own background, and while that may lessen, nothing so far suggests it will. Instead, it’s likely to be repurposed/repackaged for the new world(s), as that quintessentially American item of the superhero comic book has been transformed into massive, kung fu-inflected movies enjoyed worldwide. The Beatles show every indication of becoming a mutable source text; when I look at videos of K-pop groups, I see “Hard Day’s Night”, and I’m sure I’m not the only one.

Just want to mention what a pleasure it is to read the recent comments posted here from @LAW, @Nikki, @Michael, and others. I find them to be real meat and mead in mulling over the question of influences, and continuum of these influences, from the Beatles onward. I appreciate the thought that goes into crafting such posts.

@Michael I couldn’t post a comment on your remarks concerning George Harrison and the possible strain that the screaming might have had on him, so if I might be allowed here to do so.

I found this article particularly interesting for a couple reasons. The first is that everyone has different tolerances for noise and can be stressed in any number of ways by it.

The second is that when they say “the concerts were as loud as a jet taking off” it makes me think that some Beatles concerts could have been worse and here I speak from experience. As a military, and then airline, pilot I was always very careful with my hearing, but I have heard my share of the sound levels a jet can produce and found that many aircraft (think Concorde with four Olympus engines in afterburner) were of a lower frequency than a concert. In other words, the jet noise was not nearly as uncomfortable as what thirty minutes plus of higher frequency screaming must have been for George.

If George were one of those who, while perhaps not even realizing it, was more susceptible to this noise stress, I can readily understand how the fun and novelty would quickly wear thin.

I have never heard this discussed as we always imagine those in the audience being the ones getting blasted with the most sound, but in this case it could have been in reverse and it was those on stage getting an equal earful of unpleasant, and painful, noise.

Small point indeed, but I think you touched on something that was a factor in George’s disillusionment in touring.

@Neal, I agree, I’m really enjoying these comments. This one included.

I’ve opened up comments on the earlier post; would you mind cutting and pasting the relevant portion of this comment and posting it there, please? I have a response to this particularly that I think will be interesting.

Here’s my list of the greatest lists of Rolling Stone:

Rolling Stone – 100 Greatest Artists of the Decade

Rolling Stone – 500 Greatest Albums of All Time

Rolling Stone – 100 Greatest Pop Songs

Rolling Stone – Essential Recordings of the 1990s

Rolling Stone – 50 Greatest Blues Guitarists (White)

Rolling Stone – 50 Greatest Soul Singers (Blue-Eyed)

Rolling Stone – 75 Best Rolling Stone Magazine Covers

Rolling Stone – 10 Best Jann Wenner Betrayals

Rolling Stone – 10 Best Rolling Stone Rock Critics (Analyzing Lyrics Ignoring Music)

Rolling Stone – 10 Best Rolling Stone Rock Critics (Perpetuating Grudges of Jann Wenner)

Rolling Stone – 100 Most Influential Rolling Stone Magazine Advertisers

With regard to rock critics ignoring the music in favor of lyrics, to be fair most of them are writers and not musicians or musicologists, and therefore are more comfortable analyzing lyrics. Just a theory. I think they do appreciate good melodies, harmonies etc. like we all do.

As a lifelong auto racing fan, it’s hard to wrap my head around the fact that Rolling Stone is now owned by the wastrel son of billionaire businessman and massively successful racing team owner Roger Penske. Not that “rich guy owns stuff” is all that unusual, but RS does seem way out of the family’s wheelhouse.

Check out this epic Twitter thread on “Rolling Stone’s 500 Worst Albums” — says it all, I think!

Hahaha That is a lot of puns to come up with!

That had to take all night.

I found this really interesting article that breaks down what the most streamed songs for each Beatles album are as well as a little comment on the nature of streaming services like Spotify changing the cultural concept of albums ( This has recently been discussed with the loss of the shuffle button after Adele argued albums should be heard in their intended order). It’s fascinating seeing what is picked as the song obviously played on repeat.

https://www.google.com/amp/s/faroutmagazine.co.uk/the-beatles-most-popular-streaming-songs/%3Famp

It seems the overall top 5 are;

1. Here comes the sun- 707 million

2. Come together- 447 million

3. Let it Be- doesn’t say how many streams but mentions that it’s the third most streamed overall

4. Hey Jude- 385 million

5. Yesterday- 357 million

I tried to go looking for the streaming figures for Let it be and stumbled upon this article from a few years ago that breaks down Beatles streams by demographics and 18-24 year olds make up 30% of Beatles listeners which was a higher percentage then I would have guessed.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/markbeech/2019/09/29/beatles-biggest-fans-revealed-by-17-billion-streams-as-abbey-road-climbs-charts/?sh=58b642c62d95

The most streamed song per age group as of 2019 was

18-24 year olds- Yesterday

25-29 year olds- Come Together

30-34 year olds- I want hold your hand

35- 44 year olds- Blackbird

45-55 year olds- Here comes the sun

55 years over- Norwegian wood.

Like I found those choices fascinating and wonder what it says- if anything- about each generation.

Also in 2019 Here comes the sun was still the most streamed song with 350 million streams. Go George!

I would have guessed that the age groups for I Want to Hold Your Hand and Yesterday would be switched (I’m thinking about the teen frenzy that occurred at the time the former was released, but it’s probably nostalgia based now – irrelevant in any case when you realize it’s just a great song). Come Together’s age group is spot on IMO. Here Comes the Sun is my all-time favorite George song.

Overall, I don’t get why people don’t stream those great tracks that we haven’t already heard a million times. I’m sure they do, just not en masse. The Beatles catalogue is chock full of gems, hidden or otherwise. I never cared much for greatest hits albums by any artist. I like the orginal albums especially when it comes to the Beatles, who never produced a bad song. Not only are the hits overplayed, but there is a mood and atmosphere, and often a theme, when it comes to the original albums.

Well I found that Get Back made me have a new appreciation for Dig a Pony and She came in through the bathroom window that I didn’t really have before lol.

Dig a Pony is an underrated song. I always liked it and it’s great live.

My fave underrated songs are Baby you’re a rich man, Hey Bull Dog and You know my name (look up the number) only because John and Paul sound so happy and energetic in the recordings. And I also love And your bird can sing (Take 2) for similar reasons except I ad they were also possibly stoned along with happy lol.