- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

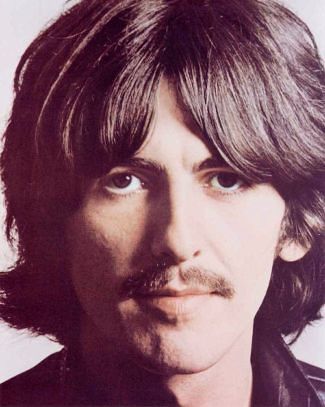

Several Beatles-related conspiracy theories—the idea that John and Paul were lovers, and the granddaddy of them all, the Paul McCartney death hoax—have emerged in the comments of late, and so I wanted to take a moment to share some strategies on how to deal with this kind of thinking. The goal should be to address the material in a respectful way—clearly it touches many people powerfully—while at the same time keeping things sane and positive.

From the age of roughly five (I know, I know) to 42, I was fascinated by conspiracy theories about the assassinations of the Sixties. I read books obsessively, watched documentaries, and listened to podcasts. And during those 37 years, I watched many, many things I first learned from “kooks” like Mae Brussell become part of the standard historical narrative. (These are many, but to name four: COINTELPRO; Nixon’s treasonous scuttling of the 1968 peace talks; the CIA’s involvement with LSD; and the American IC’s infiltration of the New Left. ) I also watched mainstream sources like The New York Times endessly lump politically inconvenient information in with the mystical or supernatural; as in 1975, every mainstream news story dealing with the JFK assassination is obligated to reference UFOs or Bigfoot, as if political murder was as outlandish as time-traveling aliens.

But more painful by far has been this: thanks to the internet, I’ve watched the conspiratorial mindset play a larger and larger role in our political culture—without delivering a single positive benefit. Most people interested in, say, the murder of President Kennedy were and are motivated by a simple desire to know the truth, so that people can benefit: Political processes can be improved, heroes and villians can be identified, and democracy can function as intended. Even Ufology comes from a deeply wholesome desire to make sense of our reality, and comfort people who have had experiences they can’t explain. The enlistment of conspiratorial thinking in the global turn towards autocracy and xenophobia is not surprising, but it is counter to 99% of the people I knew and read, and it is deeply disheartening.

To some degree, my fascination was a natural outgrowth of the time and place in which I was born. To Democratic Irish-Catholics in the 70s, the Kennedy brothers were gods, and their deaths an unspeakable tragedy. Similarly, to liberal Americans, the death of Martin Luther King was a devastating blow, our country’s racial sickness spiking into fever again, again. (Interestingly, I only came to study the murder of Malcolm X later, when I became more aware of his life story.)

I think this was a good reaction—seeking data to establish the truth in the wake of sloppy, politicized investigations. And it was spurred by an inarguable, if hard-to-define development: the loss of faith in American government. It is a very rare American today who does not feel that there is something very wrong happening in our country, and while the drivers are different, that mindset first entered the mainstream in the weeks after 11/22/63. That is an important fact.

And I will say that I learned a great, great deal of history from all this reading. I honed a sharp analytical mind and a keen sense of “the story behind the story” that serves me well to this day. Not least when I read conventional historians, or mainstream journalists, and find them wanting. Would that people like Judith Miller had been a little more skeptical and trained in conspiracy-thinking before the run-up to the Iraq War.

But in the end, this interest became bad for me. It made me paranoid and unhappy, and did not bring enough good things into my life to justify continuing. Don’t get me wrong; I still think the conventional view of these events is most likely wrong and, if pressed, will tell you what I think is more likely. But that’s as far as I’ll go—”more likely”— and given the terrible politics that conspiratorial thinking is currently enabling, you will have to press me. I do not speak of it entirely willingly.

I no longer have a craving to think or talk about these historical mysteries; nor do I feel personal threat when someone posits a different view. I feel now that my interest was at least partially motivated by traumatic events in my own life that I was attempting to solve by proxy. Eventually, I reached a point in my own personal journey (ugh) where these traumas became sufficiently loosened for me to stop this transference.

Looking back on my “journey,” I have a set of rough guidelines I apply whenever I run into conspiracy-thought. I share them below, in case they might be interesting.

- What is my attitude towards the topic? Is it very “hot” for me? When it comes up in conversation, how do I feel? Am I determined to prove others wrong, dismiss them, or assume they are ignorant, misguided or lying?

- Is this harmless supposition, or the search for a genuinely important truth? What is at stake? Is it worth the time and energy I am spending on it?

- What if I’m right? Who’s harmed, and who’s protected? Similarly, what if I’m wrong? What’s the likelihood of harm there?

- If I come to a conclusion that is different than the mainstream, does it hang on one piece of data, or many things? How specific is my conclusion — that is, how tightly am I hanging on to one, and only one, view of possibility?

- If I come to a conclusion different from the mainstream, is it filling a psychological need? Are there things in my background or personality that “tip” me towards that conclusion? What are my biases?

- How does this conclusion make me feel? Contented how that I’ve figured something out? Ready to think about something else? Or, upset and angry? Determined to spread the word so everyone knows the truth?

Let us use these to loosely address the “Paul is Dead” theory. I am not interested in arguing the minutiae of this, so please don’t attempt to engage me on them in the comments. There are plenty of sites for that; go there. I’m interested in using PID to show how these guidelines work, and can be helpful to you in a world increasingly awash in conspiracy theory.

1: It is objectively unusual to have a strong emotional attachment to the remote possibility that a musician—whom you understandably admire, but have never met—was replaced by a doppelganger. Do you know anyone else who’s been replaced in this way, much less a person under constant media scrutiny? Swapping identities is a very strange and rare occurrence, and this one is not currently supported by any benefit. (I can understand why Brian and the fellas might want to keep the gravy train rolling in 1966; but in 2019, it’s difficult to see what’s worth the effort.)

2: Let’s say William Campbell, contest winner, did replace Paul McCartney in 1966. What real world effects did this have? The Beatles continued on as before, making songs and making money, until they broke up. (And why break up at all? Why not just replace Campbell with someone who liked Allen Klein?) Paul wasn’t harmed by this conspiracy; he was, according to the theory, dead. Few, if any, people suffered as a result of this ghoulish gambit and—if the alternative is that the Beatles ended after Revolver—a lot of people actually got a lot of joy from this ruse.

3: If the theory is right, very little changes. The man who has recorded since 1966 under the name of “Paul McCartney” would admit the hoax, probably sell a bunch more Beatles records as a result, and then record under the name “William Campbell.” If the theory is wrong, I feel stupid, and move on with my life. (Please note: I am not addressing any of the more baroque theories, like those involving the Tavistock Institute, because if the Beatles were some kind of one-worlder mind-control experiment, they were a disastrous failure, and anyway, there’s no paper trail of any kind on this.)

4: If I’m crediting a bunch of photographic interpretation (“low ears!” “high ears!”), that has to be weighed against the fact that post-66 Paul has spent an entire career writing songs indistinguishable from pre-66 Paul, in addition to looking, sounding and acting uncannily like him.

5: Secrets do exist, and the old canard of “two people can keep a secret if one is dead” is hooey; successful conspiracies and secrets are present in nearly every human activity. But an attraction to this specific secret requires some self-examination, especially given that the outcome is not particularly world-changing. It’s basically a different monogram on “Faul’s” secret bathrobe. To have accurate tools for investigation, one must investigate oneself.

6) If one’s attraction to the theory is harmless fun, so be it. But remember: when you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back at you.

I second what you say here, Michael. I’d word the ending more strongly: when you stare into the abyss, not only does the abyss stare back at you, it may well swallow you up.

Yes. I met people whose lives had been consumed by “research,” and it was a sad thing to see. Not because “the truth” isn’t important, it is — but these fascinating, unsolvable riddles can occupy more and more mental space until there’s not much room left for the good things in life. I never quite got to that point — for me it was more like a hobby — but there are nicer hobbies to have.

I have a question. Why is it that The Beatles, and not say, The Rolling Stones, are the subject of conspiracy theories? No one wonders if Mick and Keith were lovers. (That’s just bizarre, actually). And no one thinks that Mick really died in 1966, and a faux Mick took his place.

Funny that you call it “bizarre,” @Tasmin, because Mick’s same-sex dalliance with David Bowie is well-established. It’s probably more likely that Mick and Keith did have sex. Or maybe it isn’t. Shit, I don’t know. I never trust the guys who spend a lot of time acting tough.

.

I’ve said this before, and better, but to me The Beatles seem to be a much more powerful psychological phenomenon than the Stones. The Stones are a great rock band, but they are distinctly of their time. The Beatles clearly transcend their time, and tap into the kind of patterns that myths do.

.

I can’t speak to the fascination of John and Paul having been in a romantic relationship because I don’t think learning this would change my opinion of either person at all. I think the sexuality of both men, and of homo sapiens as I’ve come to know it, is certainly capacious enough for that to happen; furthermore, I think the concept of “situational homosexuality” might certainly come into play with two close male friends in their late teens, or two very high rock stars, or…name your scenario. So I’m not super-interested in that issue–except insofar as a certain sub-group of fans really IS. There is a desire on the part of some fans to “queer” The Beatles, and I think this is yet another testament to the group’s continuing relevance. I think the whole John and Paul thing can, at times, say more about the speaker than the Beatles, but who among us hasn’t projected something important to us onto these guys and the group?

.

As to the Paul is Dead thing, you should read Devin’s post on it, and the book it’s taken from. He does a wonderful job discussing the mythic, totemic elements of the band in their time.

Thanks Michael. Yes, you have talked about this before on other posts. As you said, there is something about The Beatles that touches a deep, psychological place.

No other band that I can think of, has had the affect that the Beatles had, and continues to have on people.

And yes, I do know about Mick and David Bowie. I said “bizarre” regarding Mick and Keith because I just cannot envision Keith Richards having sex with another man!

It’s a peculiar thought, sure, but this article details the same kind of jealousy and love/hate that we speak about with John and Paul. To be honest, I don’t think Mick or Keith are emotionally capacious enough to think of each other as anything but business partners.

I can’t imagine Keith walking down the street wearing a “I LOVE MICK” button.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqQ21dMsfys

Haha! I can’t either!

How about “Mick Has A Tiny Todger”?

Where’s John’s hand?

That is an illuminating 35 seconds right there.

Alas, that article isn’t available in my country Michael. Yeah, there’s an iciness about them – certainly about Mick – that I don’t see in John and Paul, which explains why the Beatles ended in the equivalent of a divorce while the Stones became a multi-decade moneymaking machine. Amazing how much bad behaviour we’ll put up with from public figures as long as they run emotionally “hot” and seem to be looking for love underneath it all – we’ll forgive a needy murderer sooner than a law-abiding citizen who gives off an air of coldness and contempt. Hence, we all instinctively love Lennon more than Jagger even if he’s done much worse things.

.

As for Keith’s thoughts on Mick’s size, he’s been contradicted by none other than Pete Townshend, who also dubs Mick his only ever male crush.

Mick Pete’s only man crush? If you’ve ever seen any pics of Paul and Pete Townshend together, you might doubt that.

LOL So true, Pete positively looks like he wants to eat Paul in some of those pics.