- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

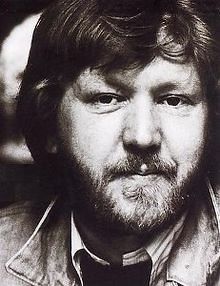

Harry Nilsson in the studio, right around the time John and Paul made him famous.

Can I just assume that everybody reading this knows Harry Nilsson? If not, scroll down to the bottom of this post, and listen—I’ll wait until you get back. (You can also go to the great Nilsson site “For The Love of Harry,” but it’s recently changed to invite-only.) Harry was one of the biggest Beatles fans around, and one of the few who could compose and sing almost as well as the Fabs themselves. He’s also a really interesting window into our favorite foursome.

“Harry Nilsson is My Spirit Animal”

In a post last May, I mentioned that, apart from The Beatles, early to mid-70s Stevie Wonder is my favorite aural blankie. Of course I forgot Harry Nilsson. Just as it’s John, Paul, George and Ringo’s Karma to be remembered, it’s Harry’s to be forgotten. Perhaps he knew it, sensed that for him fans would be fickle and fame fleeting. (Check out “Mr. Richland’s Favorite Song” on Pandemonium Shadow Show below for some poignant lyrics and Beatle references.) Fear of the trip down from the heights is a real thing, and as good a reason as any for Nilsson’s legendary stage fright. People were saying “Whatever happened to Harry Nilsson?” for most of his adult life.

But when he was good, nobody else could’ve been The Beatles’ favorite American group. Put on The Point, and I’m three again, warbling along. The songs are sublime, but the cartoon I can’t look at; it’s remarkable and painful, somehow…which is to say it captures Harry Nilsson perfectly. The Point is like a Yellow Submarine for unhappy children—smaller and darker, the lines jagged and unconfident, the colors muddy and shifting. It’s a hippie-era fable with a happy ending you sense it doesn’t really believe.

Instant Nilsson

My thoughts about Nilsson were occasioned by this instant-breakfast sort of appreciation on Grantland, which is heartfelt and certainly much better written than this post, and has at least one possible Beatles-related error upon first reading. Lennon and McCartney famously broke Nilsson big when they arrived in New York to promote Apple in May 1968, not 1967—but the linked audio isn’t dated, so maybe Lennon was spreading the gospel earlier? Perhaps the author cribbed this flub from the new Nilsson biography, Nilsson: The Life of a Singer-Songwriter, a book which I will have to get because I, like Sean Fennessey over at Grantland, am totally in the tank for Harry Nilsson.

But because I’m in said tank I hope—though I have no great expectations—that this biography will be savvy about alcoholism, because the entirely predictable progression of that disease is basically the story of Nilsson’s life. The early injuries caused by an unsteady (alcohol-sodden?) family; the years where alcohol comforts and fortifies, and the as-yet-unaffected talent blossoms; then the booze and life surrounding it subtly begins to corrode the person; the familial unsteadiness is visited on the next generation, leading to incredible self-hate and regret; more drinking; attempts to quit; then the final decay, thoughts of what might’ve been, and shards of happiness among the wreckage. That’s what I recall from the splendid documentary “Who Is Harry Nilsson (and Why Is Everybody Talkin’ About Him)?” which I saw in 2006.

Lives like these make for good drama, not for nothing are all the pub regulars called “characters.” The ups and downs are enough to wear anyone out, glorious moments full of longing satisfied, where it seems like everything will be finally put right, and the terrible, demeaning ones where it’s clear that it won’t. People like this tend to collect bystanders, innocent and not-so-innocent, and inspire fierce loyalty. Nobody’s as charming and even sweet as a drunk in the good times, nor crueler in the bad ones. Somebody called Harry “A big bunny with really sharp teeth.” It’s impossible not to take personally, but it’s just the chemical doing what it does. The human mechanism is more delicate than we like to admit.

An Excess of Emotion

Alcoholics, in my sorrowful experience, suffer from an excess of emotion. Whether this is their natural temperament (that is, what they are trying to manage) or the amplifying/disinhibiting aspects of the substance, I do not know. It kinda doesn’t matter. This emotional oversupply, which John Lennon also had, makes it easier for emotions to be captured in art. Excess of emotion not only makes a release-valve like songwriting necessary, it makes it easier in some important ways, especially at the beginning. The problem is, life’s not a song. And what alcohol gives early, it takes away later, ten-fold.

People unfamiliar with all this often don’t get it; that misunderstanding is the price of sanity. “If drinking was truly this bad for your body and mind, you wouldn’t do it.” But alcohol does work, at least in the beginning—look at Nilsson before 1973, or Lennon before 1968. It’s only later, after the mechanism is firmly in place that the toll begins to be paid and the questions come. “Whatever happened to Harry Nilsson?”

Like Peter Cook, “booze” is the answer. All those bottles—and other drugs besides—are the weight holding down the arc of his life. This makes “Who Is Harry Nilsson…” melancholy viewing. Of course, as with Cook, a bunch of friends come out at the end to attempt to recast the whole thing as something other than a tragic waste, but that’s just whistling past the pub.

“The Shadow Beatle”

Nilsson is such an interesting dude for Beatle fans to consider, and he’s particularly interesting in relation to John and Paul. To my mind, he’s an almost equal mix of Paul’s talents and John’s damage. This is what made Derek Taylor call him “the Beatle across the water.” To me he’s more of “the shadow Beatle.” I’m using the term in its Jungian sense; for those unfamiliar, here’s Wikipedia:

In Jungian psychology, the shadow or “shadow aspect” may refer to (1) the entirety of the unconscious, i.e., everything of which a person is not fully conscious, or (2) an unconscious aspect of the personality which the conscious ego does not recognize in itself. Because one tends to reject or remain ignorant of the least desirable aspects of one’s personality, the shadow is largely negative.

Shadow Beatle Paul

Nilsson is the shadow-Paul; oozing melody from every pore, a gifted songwriter and meticulous studio craftsman with an angelic set of pipes…yet almost too tuneful, lightweight, mercurial. Nilsson is Paul without the drive to achieve, to show off, to show up. He’s Paul without the bossiness, a Paul more interested in being John’s buddy than his equal…which is why I seem to recall that, in the maddest days after April 1970, Lennon briefly thought of carrying on The Beatles with Harry in Paul’s slot. (Am I mis-remembering? Commentariat, help a Beatle fan out.)

If you want to know what Paul’s life and career would’ve been like had he only had a normal person’s share of ambition, look to Harry Nilsson. Nilsson shows that Paul’s supposed flaws—his workaholism and uncompromising vision—are actually what gives his work a durable weight. Paul’s career is like a bunch of pearls, strung together to form a one-of-a-kind, priceless necklace. Nilsson’s necklace was forever being broken—by which I mean to say he was breaking it—and his pearls strewn about, discarded. This make them easy to lose, easy to forget, and ultimately valued much less than they should’ve been. As a musician, Nilsson had an embarrassment of riches, and these riches truly seemed to embarrass him.

Lennon and Nilsson outside the Troubadour, 1974.

Shadow Beatle John

But Nilsson’s also the shadow-John, a man who never healed his injuries, and whose appetites for drink, drugs, and partying overwhelmed his drive to create. Like Lennon, Nilsson’s bad habits battered his gifts until they became mere echoes of what they’d been, borrowing gravitas from hopes unfulfilled. If you want to know John’s life and career had he been a solo act—or the all-powerful frontman of a band in the way common before The Beatles—look to Harry Nilsson. A few early triumphs, then some tantalizing glimpses, and an early exit. “Whatever happened to John Lennon?”

As is usually the case with the darker corners of the Beatles story, the only Beatle biographer to really address Nilsson unflinchingly is Albert Goldman. But also as usual, Goldman gets Nilsson wrong: I do not think that Harry was primarily a self-serving vampire using the ex-Beatle to gain undeserved fame and fortune. If Nilsson had been such a Machievel, he would’ve had a much better career. I think Nilsson looked up to John. (For his part, Nilsson famously disavowed The Lives of John Lennon, claiming that Goldman “got him drunk.” Uh…yeah.) The John and Harry relationship, like the John and Paul one—and the John and Yoko one, to some degree—strikes me as a kind of teen-era surrogate brotherhood. But whereas Paul’s personality tended to reign John in and focus him on wholesome work (“Let’s write a swimming pool”), Harry stoked John’s Hamburg-era wildness. Whenever I hear stories about those two, I think of teenage boys on a ever-ramping “double dog dare.” Everybody has a friend who gets them into trouble, and for John Lennon that was Harry Nilsson.

At loose ends and looking for a collaborator, John turned to Harry. But it didn’t work—just as Yoko had Paul’s drive but not his musical talent, Harry, too lacked something essential. “Pussy Cats” was a test-run for something larger, and when that floundered, so did the friendship; John Lennon never really got the hang of having friends, poor fella. Interestingly, Paul was the only Beatle without fairly close ties to Nilsson (George’s being primarily through the Pythons Eric Idle and Graham Chapman). I suspect Paul’s strong instincts towards self-preservation kicked in whenever Nilsson was around.

Nilsson and the Breakup of The Beatles

In both the musical peaks and the emotional valleys of Nilsson, we should be reminded what a stroke of luck and chemistry The Beatles really were, and how volatile such things are. Looking at it this way, it was inevitable the chemistry of the group would break down, once other, stronger post-pot chemicals took hold. This was replicated throughout the entire musical subculture after 1967. Musicians ripen under some chemical regimens, and under others, most seem to rot. The sourness of rock in the 70s is a by-product of that rot, and Nilsson’s fade is a quintessentially 70s story.

Harry didn’t have The Beatle;s resources, in any sense of that term, to cushion his fall; he couldn’t break himself into two, and let the John part go wild while the Paul part continued making music. He didn’t have others to smooth down his rough edges, to mute his moods and blunt his self-destruction. Only he could realize his talent, and only he truly knew how big it was. If it’s smaller than everybody thinks, that’ll make you drink. Ditto if it’s bigger, too.

John Lennon eventually suffered from this same situation, post-breakup; disbanding the group was a version of AA’s “geographical cure.” Regular readers of this blog know that I’m no fan of Yoko Ono’s persona, but one thing I have to give her is that John Lennon seemed to live a quieter life under her care. I suspect that John entrusted himself to Yoko in the same way a patient voluntarily checks into Betty Ford. This explains some of what John said in his last interviews. The romantic in me believes John could’ve worked again without destroying himself, but that was a question destined not to be answered in full.

Gifts Squandered?

As I mentioned, like Peter Cook and John Lennon, Harry Nilsson has his share of people who deny that we lost anything. (This appreciation in The Onion’s A/V Club actually calls it “the what a waste myth”—which continues A/V Club’s peculiar habit of being very insightful about pop culture and pretty ignorant about everything else. “All [Nilsson’s] work is so full of life at its highest and lowest,” writes Noel Murray, “that they make the conventional wisdom that Nilsson squandered his gifts seem churlish and industry-driven.” Well, no. It’s a recognition that your choices aren’t limited to writing #1 hits or incredible dissipation. Exquisitely crafted story-songs are not a substitute for life, and shouldn’t have to be, and if they are, that’s a bad thing. Art full of emotion can trick you that it is life, if you want to be tricked, and most critics do. (Myself included.) It makes criticism seem more important.

Late-period Nilsson.

The argument goes, Peter/John/Harry was doing exactly what he wanted to do, and what right have we to question another person’s choices? This is so naive it’s almost lovable as a child is lovable—if only people truly were such islands unto themselves!—and whenever I hear it, I don’t trust the person saying it. There seems to be a…peculiar reluctance to look at certain behaviors. Call me a bluenose, but no activity supposedly done “for fun”—whether boozing or, I dunno, playing foosball—is worth ruining your health for, and if you look at pictures of Peter/John/Harry after the chemicals started to take their toll, there’s simply no way to deny that happened. Harry Nilsson died at 52; he robbed himself, and the people who loved him, not just of songs, but of life. Acknowledging that isn’t about being an entitled fan, it’s about seeing an avoidable catastrophe made inevitable by compulsion, and noting how it happened.

You’d be within your rights to ask why I’m spending a work morning writing all this. The simplest answer is that the connection between addiction and creativity is so common as to be axiomatic; and while I’m not smart enough to have unraveled it all, I do know that the misery of many creative people is fueled (or at least enabled) by a widespread desire on the part of others to look the other way. Instead they say, “What a shame Harry Nilsson flamed out,” or “What a shame The Beatles broke up.” There’s a very short distance between saying “what a shame” and actually secretly celebrating what happened—getting off on the tragedy of it, feeling that “what might have been” is always sweeter than what happens. That’s insane—I’m Irish Catholic, and I’m sick to death of that whole game. With people like Harry Nilsson—remarkable people, but also addicts in the grip of their addictions—all the rest of us can be is innocent bystanders at the scene of the wreck; and as bystanders, our job is to be truly innocent, and to see clearly. We owe them that, not as fans or appreciators, but simply as people.

Nilsson BBC Documentary (1971)

Pandemonium Shadow Show (1967)

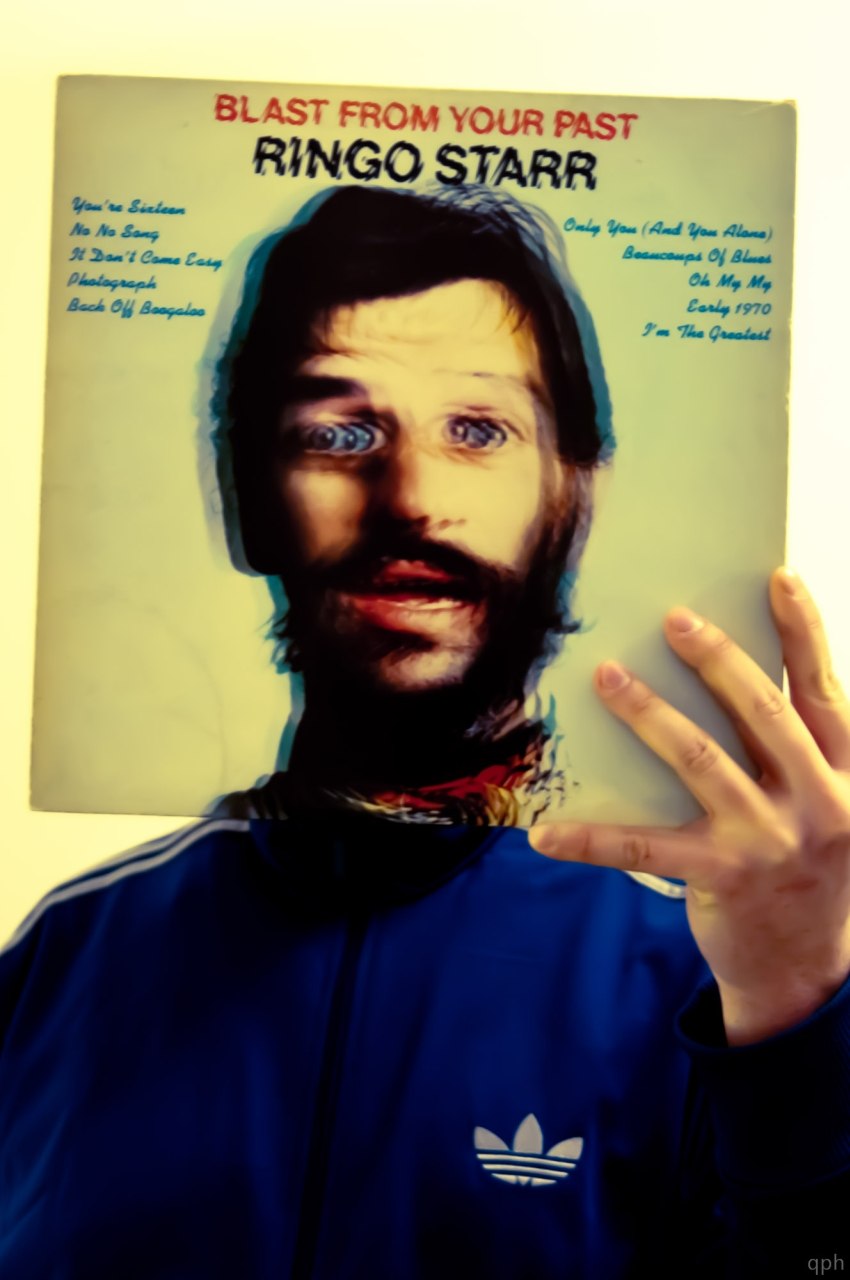

The LP that blew John and Paul’s mind.

The Point! (1971)

Nilsson Schmilsson (1971)

Michael, I think you’re spot on about Nilsson as the shadow-Beatle, and about the way he embodies aspects of both John and Paul. I love Nilsson’s album “Aeriel Ballet,” in particular, and I’m glad to see Nilsson getting more attention these days. However, I’m with you in feeling that pieces like the A/V Club one gloss over the addiction that makes Nilsson’s life truly sad, however much people want to spin it as “his choice” and no loss.

I found “Who is Harry Nilsson and Why . . .” such a good documentary because it avoided false uplift. It seems as if towards the end of his life Nilsson made some peace with things–he was in a stable marriage, and was apparently sorting some things out–but a huge amount of damage had already been done, to himself and others. Denying that because he was also able to make some good music is foolish.

The comparison to Paul is apt, but (to my mind, at least) shows Nilsson lacking in more than just Paul’s ambition and work ethic. A lot of Nilsson’s songs are McCartneyesque (“Good Old Desk” — I can totally see Paul writing an ode to a piece of furniture, too — or “Without Her,” which has the feel of “For No One”). But Paul could also write rockers (“Helter Skelter,” “Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?”) and songs with more bitter bite than Nilsson’s (“I’m Looking Through You” springs to mind). At his less-than-best Paul certainly floats off into too-lightweight territory, but that’s virtually never true during the Beatles years.

An additional connection between Nilsson and John hit me while watching the documentary: both got married young and then divorced, mostly leaving behind the son of that marriage for years. And both started over with someone and formed a new family, only beginning to build bridges between the two in the time just before their deaths.

I heartily second what you say about all this heightening the sense that the Beatles were “a stroke of luck and chemistry.” Being in a group–having four people, at least, who were experiencing a lot of the same things–was, for some years, a support to them all. As for John and Paul’s partnership, that was simply alchemic. Even when they weren’t co-writing a song, they brought out the best in each other’s work, always–even when things were breaking down. I don’t think Nilsson ever found anyone he could work with in quite that way; certainly his role with John was much more that of a sidekick than of a partner. That during the recording of “Pussy Cats” Nilsson suffered a hemorrhage of his vocal chords and didn’t want to tell John sums that up. As much as Paul could irritate John, he needed someone who could stand up to him (see Yoko).

I also hope the new biography of Nilsson will manage to approach his alcoholism, and the damages it inflicted, in a clear-sighted and compassionate way. It should be possible to celebrate the best of his music without needing to whitewash his life.

Thanks, guys–whenever one enters territory as personal as this, it’s easy to get carried away. I’m glad there were some things you found interesting.

@Nancy, the comment about Nilsson’s marriage is even more apt when you remember John’s famous comment about Julian “being born out of a bottle on a Saturday night.”

Also, I just found this review of the bio.

There is some Paulishness to his features.

Great post, Mike.

“Nilsson Schmilsson” is one of my favorite albums, but otherwise it’s a song here, a song there; Harry is someone whose music I’ve always wanted to like more than I have. (The Lennon-produced “Pussy Cats” strikes my ears as, to use Mike’s phrase, a hot mess, and not in the good, White Album way.) But none of those reservations mattered because this post was such a pleasure to read. It has the flow of something that wasn’t at all forced, where every fact and phrase flew into the author’s hand, and thence into the reader’s ear. (It’s never that easy, but the trick is to make it seem so.) I have to say again, Mike, well done.

Jesus! Harry Nilssson… I remember, as a youngster in the 1970s, hearing “I Wanna Be A Spaceman” on the radio, and running out to my local Sam Goody to buy the album. And George Harrison was on it! And I bought album after album, and they were all on these weird, orange-label “flexy disc” records… extremely thin albums. This was when records were slowly but steadily getting shittier and shittier quality, because the record companies were cutting costs. Friends told me they would melt old albums (including the paper labels) to make new records. And sure enough, records from the early ’60s still sounded great ten years later, but the newer ’70s albums wore out after only a few plays.

But Nilsson sounded different on every track! Hard rock, c&w, novelty, ballads… with an incredible, multi-octave voice… … he was unclassifiable! After awhile, I outgrew him (sometime in the late ’70s) but then years later, I was a grownup with a wife and baby, and I bought the Hal Wilner “Stay Awake” compilation of Disney songs as performed by hip contemporary (meaning late 1980s) artists, and here was Harry, singing “Zip-a -dee-doo-dah” and his voice was wrecked, painful to hear, and it was like a nail in the coffin of my teenage years.

I never attended any of the mid-1980s Beatle conventions, but friends who went told me Harry was there, and dead serious about gun control after the horrible slaughter of John. They told me he was talkative and engaged and would sign anything you put in front of him, in exchange for a lecture about handgun control.

I wish he’d been more successful as an activist. And I wish he hadn’t been screwed over by the makers of “Popeye” … he actually walked out halfway through the production, disgusted by the way he was being treated.

Don’t know where you got that story about Harry walking out of the Popeye production, but it’s not true at all.

Abe wrote: Don’t know where you got that story about Harry walking out of the Popeye production, but it’s not true at all.

I got it from “The Popeye Story” by Bridget Terry. It’s a book I bought in 1980.

I’ll type it out for you:

“Three days before ‘I Yam What I Yam’ was filmed, Nilsson left Malta tired, angry and disappointed. ‘The conditions were miserable,’ said the songwriter. ‘The other night we had a pail, a bucket, and a whiskey bottle to catch the water dripping in over the electronics. There’s usually a power failure when we start recording. And by the time you DO start recording, after clearing away the chairs from dailies, setting up the baffles for the instruments, rehearsing the tune, and dealing with the considerable personalities, it’s midnight. Next thing you know, you’re writing a song until 5:30 in the morning. And when you’re writing here early in the morning, you’re with the rats, who are very large on Malta. It’s not pleasant at all.’

The songwriter’s happiness could be traced to disagreement with the way Altman had incorporated his songs into the film. For ‘I Yam What I Yam’ Altman said ‘just do what you do. After hearing your other songs, I know your instincts are correct,’ said Nilsson. ‘Unfortunately, two or three of the songs have been butchered because of our contrary instincts. ‘Food Food Food’ which was written for Wimpy and Geezil, was then used in the rough house, sung by everybody, and it stinks except for the visuals. Music was not treated well at all on this picture.’

On March 25, Nilsson, his wife, Una, and sons Beau and Ben left Malta and headed home to Los Angeles. Van Dyke Parks, Nilsson’s musical arranger, would supervise the remainder of the recording.”

Abe, this was a book that came out the same time Popeye was released, and was meant as positive publicity for the film, but the author apparently couldn’t help but report the truth.

If you have evidence that Nilsson was happy with the treatment of his songs in Popeye, I’ve love to see it.

Nice article, Michael. It brings up perhaps too many things to comment on here. I’m not a Nilsson expert–I just know a couple of his albums–Pandemonium and Aerial–and the stories of his overlap with the Beatles and especially John. You’re right about him having strong elements of both John and Paul. Interesting… What strikes me about the two albums I’ve heard is how dated the material feels in stark contrast to what the Beatles were doing at the same time. This seems to be largely in the production–something in the strings mainly. But it points up another amazing thing about the Beatles, which was though they largely defined their era, their material NEVER feels dated–they were completely of their time and at the same time transcendent. That’s something to shoot for…

Wow, that is really true, Chris–I must admit that what I knew was Nilsson’s classic stuff, the hits from 1969-1971, and so I was just listening to Pandemonium Shadow Show for the first time last week in prep for this piece. I think you’re absolutely right about the datedness of the production. Could it be the difference between LA and London, too? There’s something very “60s LA sound” about those songs, to my ear. I wonder: do you hear the same thing in The Point, or Nilsson Schmilsson? Because I don’t really.

Re commenting: if not here, where? If not now, when? I think our record is this thread.

Most commented thread = most important topic. 😉

I think it’s a bit unfair to say Lennon squandered his gifts considering he was shot dead at age 40. He worked five years post Beatles yet is compared to the others who worked much longer. All indications were the 80s would have been a very good time for Lennon, the times would have finally caught back up to him as it were. Kind of hard to see him going wrong with guys like Andy Newmark, Tony Levin, Earl Slick, etc, on his team.