- F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Lennon - July 1, 2020

- The Artist as a Dissipated Man: Fred Seaman’s “The Last Days of John Lennon” - February 15, 2020

- John Lennon, Alma Cogan, and the Delicate Mechanism of Efficient Beatles Operations - December 21, 2019

Belatedly for someone as into the Beatles as I, I’ve been reading Fred Seaman’s The Last Days of John Lennon. It’s a very quick read, but not a particularly pleasant one. Seaman, John’s personal assistant for the last two or so years, depicts a rock star in his late thirties who may as well be in his late eighties for the way in which his happiness seems to be confined to rare moments when he reminisces about something he did in his early twenties. If there’s a spectrum of Dakota-era John Lennons stretching from Goldman’s smack-addled burnout on the far left to the drug-free, happy, bread-baking househusband on the right, Seaman’s is somewhere believably to the right of Goldman’s: functional enough to put on some clothes, walk down the block, and turn on the Lennon charm when he’s in the mood to do so, but stifled and depressed enough to retreat to his room for hours or days on end, where he does drugs, looks at Playboys or the TV, doesn’t write music, listens to Muzak versions of his own songs, and reads about psychology or the occult.

That the Dakota years were less rosy than the Ballad claims is not really up for debate anymore amongst anyone even semi-serious about the Beatles as people, not legends, but it’s still stunning to see what that looks like up close.

Weird beliefs. John appears to believe earnestly in what seem to be some pretty odd things. He is certain that Sean will inherit his soul when he, John, dies, because they were born on the same day. He believes that because Yoko was able to accomplish this feat, she has magical powers of some sort. He also believes that he is living on borrowed time and that he is headed for a violent end because he was a violent man. He is very interested in what it’s like to be shot and thinks a fair amount about assassination, which he believes is modern crucifixion. Most of us on this site don’t think about these things, but understanding the isolated, paranoid Lennon of the late Seventies probably depends on putting ourselves in the shoes of someone who did.

Exhaustion. One of the central impressions I get from Seaman’s book is exhaustion. I see someone who had given all he could give by 1966, and who knows it. Lennon’s encagement in the Dakota is enforced by “Mother” to degrees great and small, but until maybe the last six months of 1980, there’s a pervasive sense that John is choosing this. He’s exercising agency by not exercising agency. I think there are many reasons for this, some of which Seaman didn’t see (i.e., John’s about to buy a place with May Pang, swings by the Dakota for a stop-smoking cure, emerges three days later unsure of what day it is, complains of having thrown up endlessly, and ends the relationship), but that volitional laziness is present as early as January 1966, when Paul uses his break from recording/touring/filming to study piano and music theory; George, to learn the sitar, and John, to hang out at Weybridge and do LSD.

Unlike Paul, who came into his own during the Sixties, John hit the world stage shot out of a cannon. It took enormous energy to build up the charge to be shot out of that cannon, and that energy was almost entirely self-generated. Something like that cannot be sustained. Do you think that when it was gone, John knew it? I can’t imagine he didn’t. Do you think he sought protection because its absence left him feeling vulnerable? I could see that. Do you think without the animus to be bigger than Elvis, he needed something else to motivate him? Like being a guru? After the Beatles reached the “top of the mountain,” John doesn’t seem interested in pursuing his other artistic interests. He seems to be trying to figure out what’s above the mountain, and from there leads LSD immersion, compulsive meditation, the diminished ability to tell friend from foe Michael Gerber has discussed here, and various efforts to be bigger than John Lennon, Beatle.

Yoko. It bums me out to detail what the Lennons’ relationship really seems to have been like, not because I want to believe in the Ballad of John And Yoko (I don’t, codependency with a superiority complex weirds me out), but because their marriage looks so toxic for everyone involved. Yoko appears to control most aspects of John’s life, sending him to different locales, requiring him to take vows of silence, and so on, while she conducts affairs and spends an odd amount of time on the phone making business deals of some sort. (Exactly what she is doing, or why it takes 20 hours a day to do it, is beyond Seaman’s purview.) When sessions for Double Fantasy start, John retaliates in some minor ways by being a tough critic, telling her when her performances need work, insulting her in front of the studio musicians and staff, and generally behaving like someone who’s finally got fire in the belly and an axe to grind. Seaman does not really see Yoko exact any measure of retribution for this, but given everything we do see of the couple’s arguments, distance, and compulsions, it’s impossible to think she did not do so at some point.

Loneliness. John seems to need the 22-year-old Seaman as a friend and as an assistant/employee, an uncomfortable blurring of boundaries that’s both doomed not to provide him with the companionship he really needs, and an encapsulation of what’s so sad about his life in the late Seventies. If even a quarter of Seaman’s recollections are accurate, John is simply alone. Unwilling or unable to accept calls from peers who might be able to relate to him, find a supportive romantic companion, or commit consistently to the type of other-directedness that would allow him to be a real parent, two of John Lennon’s closest and most healthy relationships in the Seventies appear to be with servants whom his wife paid to be his friends—May Pang and Fred Seaman. This is put into relief by the ways in which the lawyers, widow, and David Geffen attend to business necessities after Lennon’s death, Geffen apparently not too grief-stricken to exult openly about how much money he stands to make.

When I look back at all this, I think the inflection point occurs before India, before Two Virgins, before Allen Klein. I personally think the problem begins when John gets back from filming How I Won the War and Brian Epstein is too fucked up with his own addiction and depression issues for this content and to co-lead and manage the Beatles anymore. John Lennon had enormous potential at the end of 1966, but he needed someone who, like Epstein or George Martin, wanted to help him. McCartney tried to fill that role, but they were also friends, brothers, partners, competitors. And unlike 1961—the last time they were managerless—John didn’t have a cannonball charge in him. Unwilling to defer to Paul’s leadership, but too tired to lead, John was prey for those who would manipulate his need to be bigger than [Elvis/the Beatles/Jesus Christ] while using his directionlessness for their ends.

The book leaves me wondering what it was like to be John Lennon in 1967, a gauzy year when Lennon determination was being replaced with Lennon lassitude, but access to his subconscious, and his genius, appears to have been at an all-time peak. With worse luck—no Marharishi and too many hangers-on—the story ends in someone like Brian Jones’ flat in 1968, or something. With better luck, who knows—no one would have predicted 1961 John would become 1964 John, either. With the circumstances we got, and absent some affirmative effort from him, it feels like it inexorably leads to somewhere very like the Dakota circa 1979, looking out at Central Park, and writing funny shopping lists for your personal assistant.

I started this book a month or so ago but haven’t finished. It’s interesting to read your thoughts regarding John’s slow downward spiral into nonfunctionality; I was struck in the book by how petty things became so inflated on a daily level, simply because there was nothing else going on. All the niggling anxieties might have been overcome if he’d had something concrete to do. Also, based on the cover copy of my hardcover, which promised “John’s thoughts about his rivalry with Paul McCartney” or something similar, Seaman wrote with the intent to, or the book was edited with the intent to, promote John’s negative thoughts regarding his old friends. There are a couple of more tender moments, though, which the writer doesn’t point at and call out in particular, and I wonder if those made it past the editors, like when they’re outside looking at the night sky and John says “Venus and Mars.”

(I always wonder what role either pre-or post-manuscript editorializing takes in all these books I’ve read, as a matter of fact.)

Michael, I think your analysis is spot-on. That point about Lennon’s self-generated cannon charge is so important. He burned up a lot of fuel very early getting the Beatles off the ground, and when it dissipated he must have felt truly exhausted.

.

The John/Yoko relationship has always seemed to me like almost a folie a deux. It was a complicated emotional dance they were doing, and they had both been greatly damaged as children. I think they were mostly trying to do their best by each other but lacked the tools to get better at that — and the drugs didn’t help.

.

If Lennon hadn’t been killed in 1980, I can well believe he’d have emerged from this funk and gone on to better energy. This looks like a phase he was perhaps pulling out of.

Enjoyed this Michael, even though it’s depressing to read about John in this state.

I’m curious what you think about this interview with Jack Douglas, (producer of Double Fantasy)?

https://www.heydullblog.com/double-fantasy/jack-douglas-in-beatlefan-1999/

He was one of the last people to see John, and seems to think he was feeling positive, and looking forward to promoting Double Fantasy.

He also says John was looking forward to getting together with Paul.

I’m just wondering if John was starting to pull himself out of his depression. I certainly hope so.

Thanks, @Tasmin!

Something really does seem to have changed for John in Bermuda. It seems like he realizes he takes more pleasure in doing something—making albums—than in protecting himself from everything. He also seems to gain strength as he goes. Both times this happens to him-1974 and 1980-collaborating with Paul immediately appears on the horizon. As do indications that he and Yoko might split permanently.

I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that John intended 1981 or 1982 to include collaborations with Paul and a split from Yoko. I think a lot of the spiel in those last interviews was an attempt to set Yoko up in the public and critical eye so that she’d have a rock career—what she apparently always wanted—of her own, so that John could ease out of the relationship. That’s just my read.

@Nancy, re: “I think they were mostly trying to do their best by each other but lacked the tools to get better at that — and the drugs didn’t help.”

I hope—for their sakes—that this is accurate. From Seaman’s book, I certainly get the impression it was true of John. For most of book, John relates to Yoko almost pathetically, desperate for her attention like a needy child seeking a distracted parent’s approval. But of course, we’ve also heard that he could be pretty awful to Yoko, verbally as well as physically, so it’s likely that this is only one side of the story, based on (a) what Fred saw and (b) John being particularly weak in the late Seventies.

Going outside the four corners of the Seaman book, it is harder for me to feel confident that the same is true of Yoko. After she meets John, if we’re going by actions and not words, John gets less healthy, more angry, and more disconnected from things that make him happy.

John’s new partner apparently encourages him to start taking heroin. She encourages him to sign with Allen Klein. She encourages him to end his partnership, and then his friendship, with Paul McCartney. She requires him to quit primal scream therapy, something that appears to be helping her husband calm down and work on his core traumas. She requires him to forego contact with his son. She requires him to move to New York. She requires him to move to Los Angeles with an employee she has selected while she conducts affairs in New York. When he begins to reconnect with old friends, his son, and his muse as a result of this arrangement, she requires him to return to her apartment. Three days later, he emerges, unsure of what day or year it is. He complains of having spent three days “puking his guts out.” He immediately breaks off his relationship with the employee, who was encouraging him to collaborate with Paul McCartney and returns to her apartment. In short order, he announces that he is retiring from the music business. According to multiple accounts, he begins to use heroin again, something that he may or may not continue to do for the next four or five years. After giving birth to a son—who may himself have been born addicted to heroin—she withdraws to a separate apartment. Her husband spends his time largely alone in his bedroom, a knife above his bed—a present from his wife, who has encouraged him to cut all ties with his past. She instructs his personal assistants—the only people with whom her husband is permitted regular contact—not to allow calls from his friends, family, and former collaborators to be put through. Her husband begins to show signs of serious depression and, possibly, addiction. She requires that he sign power of attorney over to her. Her husband is not permitted to travel to England, even after he obtains his green card, but the family do spend several extended stays in Japan visiting hers. Finally, after several years of this, her husband decides he would like to begin recording music again, something that makes him happy. He collaborates on several demos with his personal assistant, a 23 year old who plays percussion on his recordings, instead of with friends like Paul McCartney, Elton John, David Bowie, or Mick Jagger. She requires that she have equal space on this new album, which is to be about the couple’s marriage. However, she refuses to spend time with him that summer, encouraging or requiring him to spend time elsewhere while she carries on an affair in New York with a younger man. She asks attorneys about whether she might obtain more than half of her husband’s wealth in a divorce and is told that this will not be possible. Her husband begins working again, showing the first signs of happiness, focus, and enthusiasm in years. Shortly after the record is released, her husband is shot dead in front of her apartment. In the next few days—some say as soon as the next day—the man with whom she has been having an affair moves into her apartment and begins wearing her late husband’s clothes. She does not move out of the apartment, choosing instead to remain for the ensuing 39 years at the scene of her husband’s brutal—a site she must pass to enter or exit her home. She reluctantly permits her late husband’s first son to travel to New York after his murder, but does not allow his ex-wife to join the boy. Later, the boy must work with Paul McCartney to buy back items belonging to his late father that were apparently intended for him to receive in the event of his father’s death.

I think Yoko’s feelings for John were complex and also not complex, if that makes any sense: I think at root, Yoko is driven by a fear of being poor and of not being in control of a situation.

It’s a disturbing pattern, definitely. I think much hinges on how much agency Lennon was able to exercise at different points and how much awareness Ono had at various points. It seems clear they were both suffering from under diagnosed and undertreated trauma from their childhoods, so what either was able to do, or understand, is in question during their relationship, at least to me.

.

So I give them each some benefit of the doubt and hope that it’s accurate.

@Nancy, I think that’s a very healthy view.

.

As for the question of agency, I agree. At some level, John chose all of this. Even at his worst, he was John Beatle. If he wanted to leave, he could have left, right? I think there are some depressing rabbit holes if one thinks about things like the stop smoking incident and wonders whether it wasn’t that simple. But I don’t think there’s much to be gained from going there.

The possibility of mental illness is what really complicates things, I think. It seems likely to me that in the 70s Lennon was wrestling with depression and anxiety, at least intermittently. And if he was, his healthy agency was compromised.

.

With Ono I genuinely don’t know. She seems more opaque to me. But to survive her childhood she seems to have developed a persona focused on power and control. And that was attractive to Lennon at least in part due to the exhaustion you mention.

.

It’s all complicated and we’re at such a remove that it’s very hard to say anything definitive. I do hope they genuinely meant to do well by each other.

@Nancy, I agree that at a minimum, John was suffering from those two. I think understanding him in the seventies also means considering borderline personality disorder as well as various byproducts of all that LSD, amphetamine, cocaine and heroin use. Due to the stigma around these things, biographies skate around these issues as though John’s story can be explained without considering them, but that’s really not possible. And any one of those would help explain things that are so mysterious otherwise. For example, Google borderline personality disorder and abandonment (I’m on my phone or I’d share a link), and compare it to John between 1968 and 1970.

Yep, bipolar is a strong possibility. And LSD wasn’t good for Lennon, long term. All in all it makes it hard to determine how much understanding and/or wherewithal he had at any given time.

And people serious gave Mccartney shit for holding a grudge? Yoko was toxic to the core!

Couldn’t agree more with all of your comments.

@Michael Bleicher

Michael,

I am new to this blog, but am finding it extraordinarily compelling with this post in particular, as well as your reply to Nancy, proving remarkably trenchant–perhaps the most trenchant I have run across in the flow of Beatles commentary.

Your point about Yoko’s feelings being complex while also not be being complex does indeed make sense. Most striking however, is your determination that John allowed this to happen. Even though I realized years ago that neither I, nor anyone else, could ever divine the exact dynamic of their relationship, it never really dawned on me that he was the one who had to have opened the door and then held it open for far too long. Even then , who knows if it could have been closed again?

I had, for many years, questioned why he simply didn’t walk away from what was obviously a fraught existence–ah, but such was the naive thinking of my youth!

I get the feeling he probably did not know how to…and that is assuming he could have even held to that decision had he made it. Am I correct in reading your post that way or am I drawing the wrong conclusion.

The other point that I noticed in reading the comments to this post, is that I might be in a small group of individuals who, other than for a set/formal interview, would frankly preferred not to have met John or Yoko to “hang out” with them. To me too much of that desire strikes me as those who, for example, wish they could be transported back to see the Battle of Gettysburg play out. Errrr…they would be shocked at how quickly that wish would change if they were there for 60 seconds. I guess what I am saying is I just would not quite sure know what to do and this goes far beyond that shopworn and trite saying that it is better not to meet one’s heroes. I just wouldn’t, even today, know what or who they were.

From reading your post I had the nagging feeling that not only was John’s demise tragic, but a good part of his life seemed to be so as well–a view I know many strongly disagree with. If the time machine could take us back, I would gladly give up my seat so that someone else could meet them.

Thank you, Neal, and welcome!

Sadly, I agree with you on all counts. I think John in 1975-80 was stuck: he knew his current situation wasn’t making him happy, but he had given over much of his agency to Yoko, who was only happy to take it. Bereft of the ability to decide (and sometimes even think) for himself, he shriveled, as just about anyone would under such circumstances. I think he had the potential to change course somewhere in there — this was the guy who imagined what the Beatles could be — but I don’t know if, by the late Seventies, he had the strength. It would have taken as much strength as it took to make the Beatles happen in the first place, but he wasn’t twenty any more and had had his freedom and self-assurance nuked to bits by his arrangement with Yoko in a way that Julia/Freddy/Mimi/Alf/Stu’s absences/issues/deaths hadn’t done.

I also sadly agree that much of John’s life was tragic, too. Most people disagree with it because (a) it’s not the story that’s told over and over by official or quasi-official biographies or the Estate and (b) it’s really uncomfortable and sad, if you like the guy and his music, to realize that the arc of his life is fundamentally tragic after 1966 or so. But to me, a summary is something like: “gifted, disturbed boy with tremendous amount of drive to outrun a bad childhood discovers love for music and creative soulmate(s) and gives everything he has to become the most famous musician in the world, hoping it will make him happy. He does, but it doesn’t, and people who don’t have his best interests separate him from his friends, his creation and creative spark, and ultimately himself. He’s too screwed up by addiction, mental illness, and unaddressed traumas to change things, so he retreats further into addiction and mental illness, wishing he could somehow regain his lost spark. He makes a few halfway steps toward doing so, but they’re not enough, and ultimately he is killed in front of his apartment building where, 24 hours later, his wife installs the man she had been sleeping with behind his back.”

@Michael B – Yes, and I would also add that it took both John and Paul (as well as others, but mainly them) to make the Beatles happen. They ‘drew power from each other’.

By 1975, John had been completely isolated. Not only from Paul (who had been set up to send him back to Yoko), but from all his family and everyone else who loved him and could help him.

It would impossible for anyone to find that sort of strength without human support.

You know, MB, every time I read this I’m struck anew at the fact that John did not go back to England/was likely “advised” not to go to England because of Mercury retrograde/etc. and I’ve rarely seen it commented on. Oh, he wanted to, everyone says! But he was so busy! So busy he could go to Hong Kong, Bermuda, Egypt, and Japan, but couldn’t go to England to see Mimi or Julian or his sisters or anyone who loved him, really.

@Kristy It’s very sad, and completely illogical. One of those things people are simply asked to accept — John Lennon was “too busy” traveling to all the other countries you mentioned, or sitting around the Dakota overseeing a retinue of househould staff, to see his relatives, or any friends. Phillip Norman’s book tells us that John enjoyed the company of Yoko’s PR man, Elliot Mintz, but Jack Douglas – who by all indications actually did become a close friend – says that Lennon hated Mintz. Either way, it strikes me as odd that John Lennon was apparently happy to have no friends who were involved in the arts for five years.

There’s also an interesting anecdote in the Peter Doggett book about Pete Shotton coming to visit in the late Seventies. The first night, John was really funny and his old self. The next day, Pete called, and could hear Yoko yelling in the background, then John said, “look, he’s coming over and that’s that.” That night, John was incredibly subdued, Yoko was present, and they mainly talked about macrobiotic food.

Wow, what a great article.

I’m very taken with the concept of Lennon’s creativity being a cannon that launched itself and was then left exhausted.

It makes so much sense. He was always searching for a way to re-charge the cannon- LSD drugs, Maharishi spirituality, Politics being relevant and cool, and Yoko filled that space for him. Seemed to fill a negative though.

Not Yoko bashing here, but a relationship is a jigsaw, and some people fill the bad spaces in the jigsaw and some people fill the positive. Unfortunately John was lead into the negative jigsaw I think and he so needed the positive and couldn’t discern the difference.

Or maybe he could, and preferred it that way.

I have definite thoughts about all this, @Michael, as I’ve shared with you privately. I will keep those thoughts private, mainly because they are just too depressing to share widely.

.

Simply from his behavior and statements, the Lennon of 1965 and the Lennon of 1968 were very different. Young Lennon is witty, quick, often witheringly critical of society but perceptive of it and desiring to conquer it. He’s really on fire to create work and prove himself — to “show ’em” — and thus runs into a double-whammy in late ’66. One, he HAD showed ’em; and two, he didn’t know what he wanted to do next.

.

What do revolutionaries do after they win? Mao made more revolution, much to everyone’s pain, and John did his own version of that until the Beatles broke up. He knew he didn’t want to be Fat Elvis, but that’s not a career. Avoiding irrelevancy and self-parody isn’t a life.

.

Actually, there’s something more here that’s worth mentioning: the new rules of Sixties stardom, which The Beatles were primary authors of, insisted that celebrities remain relevant to the times. Because the times are changing faster and faster, this requires either a rejection of relevance in favor of authenticity (like Paul or George), or a chameleon-like, neurotic reinvention of oneself (like Bowie or Lou Reed or Madonna or, to a lesser degree, Prince).

.

Both Paul and George had, by 1975, solidified into the people they’d first grown into around 1968, and neither was overbothered if a fan didn’t like who they were or what they were into. Ravi’s playing an hour of ragas for the first set, and fuck you if you don’t like it. Linda’s singing on my records and we’re bringing the kids on tour, sorry if that’s not hip enough for you.

.

John never really got to that stage, and I think it’s not wrong if it feels like…immaturity? on his part. Twelve-Step culture says your emotional development stops the age your addiction begins and, particularly as I’ve gotten older myself, John Lennon has increasingly felt like he missed some developmental stages. Maybe or maybe not, but first John tried the reinvention game — as a guru politician, then as a confessional everyman — but found his limits rather quickly. John got bored; he didn’t like to play dress-up; he wasn’t even much of an extrovert (that’s why your cannon metaphor is so apt, Michael). Lennon’s gift wasn’t as a performer, it was a certain immediacy and sincerity. And I think his anger at fans during the Seventies was at their ability to consume an artist and — if not attracted by a new persona — move on. I think by 1975 Lennon was feeling a kind of rejection from fans that he hadn’t felt before, and he didn’t like it. Ironically, the DF-era Lennon is an attempt to mix reinvention (“I was a rocker, now I’m a rockin’ dad!”) with the kind of personality that recognizes finitude as the price of authenticity.

.

But it didn’t really work, did it? That’s why I’ve always felt that if Lennon had lived, The Beatles would’ve anchored Live Aid. Of the two of them, it’s Yoko who can show you endless glimpses without showing you the real her; this is why Yoko has always moved so easily in the post-Warholian art world. She is artificial in the time-honored way of the aristocrat. John wasn’t like that, couldn’t do that. Even when he bought his manor, it was in an apartment building around the corner from a drugstore.

@Michael, great points. Your points about Lennon not growing into an adult self reminds me of Hunter Davies book, where he notes that Cynthia tells John, “you seem to need the other more than they need you.” The closest we get to John’s best self seems to be who he is in 1965. In fact, he’d been preparing for that since 1956. Problem was, like the other three Beatles, he discovered he needed some space from his Beatle self. But unlike Paul and George, who had saved something of themselves for themselves, John had poured everything into becoming a Beatle–so the remainder of his life is him trying to figure out what else he could be that (a) would be fulfilling and (b) not rejected by others.

.

I think much was happening in 1980, but I get the distinct impression that John decided he wanted to a little more wholesome, charming, and Beatle-y again, because he realized he was happier when he had a clean, no-warts public self that was easy for fans to like, even if (or perhaps because) it was a big con and not Authentic. He even wore a moptop haircut again.

.

I agree about Lennon’s development stopping somewhere in his teen years, as far as available evidence goes. Even Lennon in 1980 reminds me of me at 16 or 17: smart enough to have figured out intellectually what sounds right, but developmentally too young to actually feel those things to be true, and act accordingly. I do get the sense he was trying, but unless/until his surroundings changed, I think the deck was stacked against him. And I don’t get the impression he was sure he wanted to change if it was going to be hard, because I get the impression–confirmed in Seaman’s book–that John felt he’d done all the hard things he could. There’s something familiarly adolescent about how John compulsively tries on identities, hairstyles, fashions, political beliefs from 1968 onward. Yet Young John doesn’t do this; he’s basically consistent from 1962 through early 1966. That looks like regression to me.

.

One other thing, had Lennon lived and been determined to survive: I don’t think the chameleon-like personality revamps every 18 months would have changed. I think they would have gotten weirder and more extreme. John’s talk about touring, and the route his contemporaries took, makes it easy to imagine him as another elder statesman of rock, touring his back catalogue with a band of season pros (and some stupid tour names–McCartney’s tour is called “Freshen Up,” the Stones have had a “Zip Code” tour and a “No Filter” tour), showing up on Fallon to promote his new solo album etc. I don’t think he would have condescended to do that. I think he would have seen that as being a performing flea. I see him ending up much more like George–an eccentric torn between his need to protect himself with his money from people who scared, disturbed, and sought to use him, and someone who bemoaned the distance his money created. That’s the difference between New Celebrity, which John and the Beatles invented, and Old Celebrity. I think–pardon the expression–John would have rather died, so to speak than become part of Old Celebrity.

Michael B., good point about John’s aversion to “Old Celebrity.” I thought about Lennon’s reaction to fame when I read this passage in the new novel Opiod, Indiana by Brian Allen Carr (which I recommend):

.

“I feel like there are two types of misery in this word. There’s not getting what you want and being angry. And there’s getting what you want and being sad.

.

If you’re either one of those–if you’re miserable–you don’t know what will fix it. You go back and forth forever. Wanting a thing. Pursuing a thing. Getting a thing. Not wanting it. And you start all over again.”

.

To me, that gets at something important in Lennon’s experience. He got to the toppermost of the poppermost, got the money and the critical adulation, got all the women and drugs and cars and houses, and was still sad.

.

I wonder if part of the deep root of Lennon’s animosity toward McCartney is that McCartney wasn’t sad in this way. He went through some bad emotional times, especially around the breakup, but fame and getting to perform made (and makes) him essentially happy. He just doesn’t take on board as much of the angst as Lennon did.

.

Totally agree with you about the dopey tour names. “Freshen Up,” really? Can no one near McCartney tell him straight up that that sounds like a personal hygiene product? I have great affection for him but he definitely causes me to facepalm sometimes.

@Nancy, that’s a great quote and one that I think applies very much to Lennon. In fact, if I were to write a short summary of his life, it would be “gifted boy abandoned by his parents seeks to become the most famous person in the world to make up for it. He does and finds he is still not happy. He tries to find something that will make him happy.”

And I think the reason 62-66 Lennon is so compelling is that that he hasn’t yet realized that all this won’t make him happy. He’s focused and intent on achieving a goal, and that’s a sight to behold.

@Michael, to me early Lennon isn’t compelling because, as you wrote, “he hasn’t yet realized that all this won’t make him happy.” He’s compelling to me because, in this regard, he’s still living a life that is similar to most people’s, in kind if not degree. You get born, realize the flaws of this existence, and then attempt to create meaning anyway, usually through work. Wealth and acclaim either come or don’t, but as the years pass you realize that they have nothing to do with why you’re doing what you’re doing.

.

Lennon is compelling when he is a functioning artist making things that he (and others) love. The moment he stops doing that — either for politics, or for his marriage, or because of depression — he becomes mostly boring, and more a cautionary tale than a story of success.

I think this is correct. Old Celebrity is what John meant by “playing Vegas.”

.

I strongly agree that the Lennon we met from 1962-66 is consistent, and that’s in part why he’s so appealing. Lennon after 1967 is, to be honest, an extremely interesting high school student. He shows no real adult competencies, seems obsessed with external beliefs and fashions to give himself coherency and meaning, and is primarily defined in relation to others—-positively or negatively.

.

To be frank, I find post-Yoko Lennon incredibly boring, without the context of the Beatles. And I think that’s because he himself was bored and depressed; some part of that was what Nancy quoted —- getting everything you ever wanted and finding that your problems still remain —- and some was clearly neurological changes brought on or exacerbated by drugs, as well as some sort of untreated illness.

.

Wealth and fame is like a radiation. Long term exposure seems to be very bad for people, and occasionally the damage is so vast that we on the outside can see it.

Oh please, Michael, let me hear them!

As for you, Michael-who-wrote-the-article, my instinct says, like Donald Sutherland’s Mr. X in Oliver Stone’s JFK, “You’re close, you’re closer than you think…”

@notorious, I think if you’re interested in this stuff (and as Michael Gerber has warned, it’s not exactly pleasant), it’s where Goldman’s book is useful. Not for what it says but for what it comes close to saying, but does not say. And I think this, as much as protecting the Lennon brand against the various revelations that turned out to be basically true, is why the Estate and Rolling Stone worked so quickly to discredit it. Goldman got details wrong but he seems to have had a nose for sniffing out themes or arcs that were true: John hit, he was bicurious, drugs took something out of him, etc. As I mentioned in the post, I find Seaman to be a less tabloidy, more believable source, but they and other unofficial sources all point in the same directions.

@g_i_b, I really don’t think it’s ethical for me to share those surmises, first because they are just surmises —- by now they could not be confirmed. Second, because I really don’t want them confirmed —- they have already muted my pleasure in this topic, and that is not something I wish any other beatlefan to suffer. And third, they wouldn’t change anything. It’s all history now, and better to have the story we have, as sad as parts of it are. Plus —- and this is not nothing —- my surmises would likely sadden and infuriate many fellow fans, and as a somewhat public person I would like to be able to work in media, go to conventions, etc, without being That Jerk Who Thinks XYZ. Because I’m not really sure I think xyz, anyway.

.

But I thank you for asking. I’m not being coy as much as kind. If a person comes to similar conclusions, as @Michael seems to have, I will share the sources I collated, so they can decide for themselves…if they seem to have a very firm and functional mental state, as @Michael seems to. But even then, I feel great qualms about it. It’s probably best that I simply remain silent on this topic, though the blog forces me to dance around it constantly.

.

Have a good day; thanks for reading!

Great discussion. I just wanted to say that I appreciate this from Michael G:

“@g_i_b, I really don’t think it’s ethical for me to share those surmises, first because they are just surmises —- by now they could not be confirmed. Second, because I really don’t want them confirmed —- they have already muted my pleasure in this topic, and that is not something I wish any other beatlefan to suffer.”

I read Goldman’s book many years ago, and it disturbed me. I don’t want to be naive about the reality of who John really was, but I also don’t want to know the ugliness. I think we all get that John probably had mental illness, as well as addiction issues. But the disturbing details, I don’t need to know.

I like remembering John in the period before Yoko. He looked great, was productive, and was still friends with his fellow band mates. He was funny and happy and wrote fantastic music. That’s the way I want to remember him.

@Tasmin, thank you. But I am talking about things much more disturbing (to me at least) than a depressed rock star.

.

That having been said, I think it’s really important to keep one’s passions as nourishing things, and not another species of dashed hopes and expectations unfulfilled. So your comment resonates with me, too.

Michael,

I appreciate your analysis. Thank you.

One question. Why do you think, Paul McCartney, assisted yoko in reuniting with John, after may Pang, knowing the negative effect yoko had on John. One would think, Paul, would of encouraged John to stay away from ono? Why , would you think, Paul encouraged John to reunite with John?

[…] The Artist as a Dissipated Man: Fred Seaman’s “The Last Days of John Lennon” February 15, 2020 […]

In reading this again, I’m struck by this:

“He also believes that he is living on borrowed time and that he is headed for a violent end because he was a violent man. He is very interested in what it’s like to be shot and thinks a fair amount about assassination, which he believes is modern crucifixion.”

This is very spooky. There are schools of thought that say you bring about things in your life by thinking about them. Like the power of positive thinking.

I’m not saying I believe that, but it is strange John was obsessed with dying a violent death, and about assassination, and that’s how he dies.

Was he thinking this because of the assassinations of the Kennedys, and Martin Luther King? Or was he having a premonition?

Also, why if he was concerned about this, why was he walking around so openly in New York?

Sorry, I guess I don’t remember coming across this before in my reading about the Beatles, and/or John.

It really is creepy.

@Tasmin, John was a product of his time, and that generation was absolutely fascinated with the assassinations of the Sixties, not just as murder mysteries, but as a kind of mass emotional phenomenon; imagine the death of Princess Diana times a hundred, three times in the span of less than five years. In John’s day, if you were an important liberal political leader, you were assassinated. When he started espousing political beliefs, he naturally would’ve thought a lot about the possibility of violence. I do not think he was strange in this regard; compare someone like Harvey Milk.

Michael, the death of Princess Diana is a good analogy. I remember watching the news for hours after she was in the car accident. It was so tragic.

I figured the assassinations of the 60’s were a factor in Johns thinking.

@Tasmin, it’s really creepy. It’s something I’ve read in a couple other books (not many), so I’m inclined to give it at least some credence, albeit with the necessary grains of salt when talking about people’s recollections of a murdered rock star who loved make myths, and whose post-death earning potential depends on all sorts of myths. Anyway.

I think Lennon’s thinking about Stu Sutcliffe and Bob Wooler; Cynthia and other women (he implied there were more in the Playboy interview, I think); possibly that sailor in Hamburg he may have mugged; maybe others in Liverpool. John Lennon pre-1964 or so is both very driven and has the capacity to be very dangerous. Paul Sutcliffe, Stu Sutcliffe’s sister, is on the record saying that John kicked Stu in the head with cowboy boots and that’s what led to Stu’s death. Whether or not that’s actually the cause of death, if Pauline is telling the truth–and going on the record in the early 80s saying John Lennon basically murdered his best friend was not something you’d do lightly–it’s more than possible John blamed himself for what happened to Stu. That alone would haunt him. Then you have the Wooler incident. Etc., etc.

I strongly suspect Lennon confronted/revisited a lot of this stuff during his LSD phase. I imagine it profoundly disturbed him–how could it not? And he seems to have genuinely but superficially believed in the ideas of karma and reincarnation. Not like George, but in the way that a lot of people from his generation were exposed to and vaguely incorporated those ideas into their lives. I can see John feeling deeply guilty about being alive to enjoy the success of the Beatles while Stu was dead. I can see John dealing with this by deciding that if he too met a violent, premature end himself, it would balance out–so that next time around, he was reborn better. And Lennon’s attitude toward death, after living with the very real possibility of assassination since 1966 AND probably some pretty scary hallucinations on LSD with Stu/Julia/George/Brian popping up from his subconscious, was probably very different from the average person’s. Didn’t he say he wasn’t afraid because it was just like getting out of one car and into another? I’m not sure I believe he wasn’t afraid, but I can sure believe he felt differently about it than the average person.

Last, I think John saw what happened to JFK/RFK after their assassinations: they became secular saints. He couldn’t miss the parallels between how the culture deified JFK, and Jesus Christ given his obsession with messianic figures. And as someone who had basically been trying to become a guru or Avant Garde Jesus since 1968, I can see him being somewhat sanguine about what would happen to his legacy afterward. He probably compared that to how Elvis passed away, too. With all of that burbling around in his mind in the Dakota years, no longer asserting relevance by making music, wasting away on drugs and weird diets, I can see how he would end up spouting something like that off to a personal assistant after a few joints in Bermuda.

Thank you Michael B for your great reply.

It’s clear there were many different factors which led to this thinking by John. It makes more sense to me now.

I still find it strange that’s how he died.

It’s definitely weird and unusual. He seems to have been thinking about it since the peace campaign in 1969, when he almost gloats, “they’re gonna crucify me!” in the Ballad of J&Y. If there was a way to achieve martyrdom without having to actually become a martyr, John would’ve been all over it.

He seems to have been thinking about it from very early on, actually, which just makes it even more creepy and disturbing. I would also venture to say, without elaborating too much, that this exceeds a merely neurotic man grown paranoid through witnessing contemporary tragedies, especially as the import seems to reverberate beyond the man himself. I do apologise if anybody finds this upsetting. But here a few examples of portents as I can think of them offhand:

In 1963, he told Sonny Freeman (then wife of Robert Freeman) that he expected to be shot one day.

In 1965, he apparently quipped to a reporter that he would die by being “popped off by some loony.” (I can’t find the original source on this one, but I’m sure I’ve seen it substantiated.)

In 1964, he had a joint tarot reading with Jayne Mansfield, and the card reader reacted in horror, saying they were both going to meet tragic ends. In 1967, after Mansfield was killed, he told Chris Hutchins (of the NME): “Jayne was born on April 19 and died on June 29.

April is the forth month and June the sixth. If you put them together you have one ten. I was born on October 9, the ninth day of the tenth month. Jayne Mansfield died two months after her birthday, that means that I’m going to die on one day with a nine, in the month of December.”

When Lennon’s character is shot in ‘How I Won the War,’ he looks into the camera and says: “You knew this would happen, didn’t you?” (Not withstanding the context of occurring within a film, this is very unsettling.)

Back to the peace campaign, there is also that moment (filmed) when he opens a letter by someone claiming they determined through a seance that Lennon would be assassinated. He tries to laugh it off, but he looks like he’s just shit his britches.

In 1970, when he invited his dad to Tittenhurst on Oct 9, he went berserk screaming -among other things- that he was going to die an early death.

In 1974, when Yoko went to see the psychic Frank Andrews, he told her that her husband “sleeps in blood.”

I think it’s in John Green’s ‘Dakota Days,’ that Lennon explains, emphasizing a sense of borrowed time, that he returned to Yoko and the Dakota because it was “too late in the game to change the players.”

Lennon’s reportedly last recorded demo ‘Dear John’ has a very depressed sounding Lennon repeating “Dear John….don’t be hard on yourself/the race is over….” before lapsing into fragments of ‘September Song’ i.e. “the days dwindle down/to a precious few…November…December…” ‘Help me to Help Myself’ and ‘Borrowed Time’ both have comparable themes.

Whatever Lennon told Jack Douglas in the control room on Dec 8 was disturbing enough for Douglas to erase the tapes overnight and refuse to talk about it for the next 41 years. (Goldman claims Lennon ranted about his own death. While this seems probable, Douglas seems to have upheld his silence, so Goldman may be speculating.)

Finally, Yoko’s own recollections of Lennon’s last days are also rather dark. (Why me? Why you? Broken mirror. White terror.) She says they could feel death around them like a fog. And Lennon sat in his own listening to ‘Walking on Thin Ice’ obsessively over and over.

https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/john-lennons-last-days-a-remembrance-by-yoko-ono-62533/

I wonder if she knew about it?

I remember the last time I saw “How I Won the War” in the theater (three or four years ago), that was a sad moment.

@Matt – The Jayne Mansfield connection is so weird because she was recruited into The Church of Satan in 1966, according to this article:

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/culture/secret-history-jayne-mansfields-bizarre-connection-church-satan

Was she being used to get to the Beatles because of the tarot card reading with John? Maybe that gave them the germ of an idea.

I think the letter from the fortune teller read out at the bed in was staged. It’s just too convenient for that letter to arrive at the very moment John and Yoko were giving a press conference to the world.

Great. Any time I come across the scene in The Omen where the photographer gets decapitated, I’m going to think of Jayne Mansfied now.

But you left out the part in “Dear John” where, after he sings “the race is over”, he adds, “You won.” Which is why he shouldn’t be hard on himself.

Folks here may know more about Lennon than I do. My impression is that from late in the Beatles period on, Lennon was running out of creativity. There were moments when politics or New Age spirituality or his life experiences gave him a little material, but basically, as he said, he dug rock and roll, he didn’t dig much else. And what was there left to do with rock? I could easily see Lennon going on to participate in some overproduced super-group one-offs, perhaps alternating with bouts of sparse-production recordings of oldies and the like, but none of this really very good. So much of what he’d done had been means to the end of getting rich and famous and he’d done that, so why keep on? I just don’t have the sese that he really enjoyed making music the way McCartney seems always to have. He had used people a lot and naturally he felt he couldn’t trust them, except perhaps for Yoko in a strange dependent way.

Lennon created almost all of his best music with the support of an exceptional team: McCartney, Harrison, Starr and Martin. Having deprived himself of them and the lacking the discipline of the Beatles’ recording schedule, he struggled musically and personally.

Lennon tried to replace his creative team with Yoko, Phil Spector, Allen Klein, Harry Nilsson and others. But they tended to be enablers–and often simply malevolent. Still, blinded by his mental illness, Lennon himself chose them.

His mental illness and behavior–which had given him and those around him severe problems since his adolescence–grew worse. Lennon’s unbounded wealth and privilege prevented him from hitting bottom in his drug dependence , so he never sought competent care even as his depression and personality disorder became disabling.

Despite his fear of turning into Elvis, Lennon wound up much the same. Living in a goldfish bowl, addled, out of shape, clinging to odd beliefs, a vestige of his younger self.

This is very good.

.

Further, you could see his rejection of his earlier support team as a marker of worsening illness. He had to choose between his addictions and everything else, and he chose addiction. And then he surrounded himself with enablers and fellow addicts of the most egregious sort, simultaneously building a whole myth around it, claiming that it was precisely the reverse of what it was.

.

This is typical for someone with his disease.

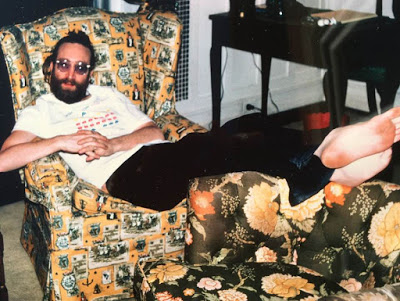

Have to say in some pictures (particularly those that accompany this terrific post) John doesn’t just look skinny, or a bit older than his years/worn out…let’s not mince words here there are a lot of shots from the last weeks/months of his life where he looks absolutely ghastly. That picture of him at the Double Fantasy sessions with Yoko standing over him he looks almost translucent. If nobody knew who John Lennon was or looked like and I showed you that picture and stated it was my friend, about 50 years old at the time in stage 4 of some horrible illness with a month to left not a single person would question it. And that could be said with more than few pictures of John in 1980. Something was going on with him health wise and it was nothing good.

@Henry, that has long been the rumor. Most notably AIDS. But that could’ve been simply anorexia, as well.

.

In any event, it is truly sad to see.

John didn’t do the interview rounds for Double Fantasy, but I well remember him doing Dick Cavette interview for STINYC and he and yoko doing “woman is the n….” song on that show, so I don’t think that had he lived, it could be argued he wouldn’t have done the “performing flea” routine for a new album or song. In seventies, concert tours were beginning to be named, but I’m sure had John lived and toured, his would have named who knows what, probably with wilder names than recent tours from older acts. To use the contemporary terms, had he lived , John would have caused as much face palming and cringing as he did in early seventies. I it saw at time, but had long forgotten about his Cavette appearance and performance until I stumbled upon it online.

Re: John’s appearance, nothing would surprise me. We know he smoked 40 cigarettes a day; he may have used needles for his heroin; he certainly had unprotected sex, God knows who with. What’s stunning about the late 1980 photos is that by then, he’s not just staying in bed all day. Plenty of British rock stars were nocturnal drug addicts, not all of them looked like 50 year old cancer sufferers in 1980. Whatever was going on, it was taking a serious toll on his body.

Michael B., I recall reading about the macrobiotic diet that Lennon was evidently following at some points, and thinking that it could deplete anyone who hewed strictly to it. Some combination of restriction (of food, of exercise, of meaningful work) and overindulgence (in cigarettes, weed, heroin, whatever) really did a number on him. It’s sad to see.

Regarding the macrobiotic diet, please see the Thanksgiving 1979 photo included with this article. You’ll notice the carved turkey prominently displayed.

John may have dabbled in macrobiotics but I believe the diet served mainly as a psychological balance for the ways in which John and Y were harming themselves, namely heroin. It isn’t uncommon for addicts to use such a balancing tool to justify addiction. It reminds me of heroin addicts I’ve known who always appear publicly with starched and creased clothing.

When I read about John’s demise, I always remember how shocked the attending physician was at the physical condition of Lennon’s body. And he wasn’t talking about the bullet wounds.

For decades, I’ve given Y much more than the benefit of the doubt. And I’ve avoided reading material that might influence my capacity to do so. I’ve since concluded that much of the karma set in motion by her — and to which John contributed — makes her chiefly responsible for his murder. And she knows it. She built her stature and artistic success on his back and once John was murdered, she chipped away at his legacy to increase her own.

What did the “attending physician “ note was the physical condition of John’s body? I would be most interested. Thank you

Michal B. I noticed in your post you said: “I personally think the problem begins when John gets back from filming How I Won the War and Brian Epstein is too fucked up with his own addiction and depression issues to co-lead and manage the Beatles anymore.”

I am a little confused by this. In what world did Brian Co-Lead the Beatles? Do you mean Brian co-led with Paul? The thought that Brian ever led the Beatles, even for one minute, is odd, no? Managed, yes, led no. Even the idea that John led the Beatles is absurd to me. I don’t think there was one minute after Paul joined the Quarrymen that there wasn’t a fluid, joint leadership between John and Paul. I don’t know why this idea of “leader-John” continues to this day when we have so much support to suggest this was never the case.

The co-leaders of the Beatles were always John and Paul. In fact, in the late 60s, Yoko comments that John had lost power to Paul during this period due to his “More Popular Than Jesus” comment — and that by bringing her into the studio (as backup) he had regained some power (doubtful. Attention? Yes. Power? No) meaning that Paul was the more powerful one in 1966. I really hope that someday we can move past this and accept that John and Paul were always the leaders of the Beatles.

And Brian? John mentioned that he didn’t have much to do with Brian for the last two years of Brian’s life because of his own “personal problems” which he felt guilty about after Brian died. And Brian, well, he did what managers are supposed to do which is to suggest projects and make them come to fruition. But did he write the music or play the music or make any of the artistic decisions? Nope. Apparently, near the end, Paul was discussing MMT with Brian, and he was going to help bring that to life, but again, that’s his job as manager. Was he leading? No. And later, was Klein the co-leader of the Beatles? Um, no. Co-destroying perhaps 🙂

@Lily, it’s canon that John Lennon was the leader of the group, deferred to by the others. And it’s canon because it’s really well documented in the texts. Paul himself agrees with this reading of the group’s dynamics, and it takes all of five seconds to find this, from Paul’s own mouth: “We all looked up to John. He was older and he was very much the leader – he was the quickest wit and the smartest and all that kind of thing.”

.

And five more seconds: “Nobody cared as much as [John] did about being the leader. Actually I have always quite enjoyed being second. I realised why it was when I was out riding: whoever is first opens all the gates. If you’re second you just get to walk through. They’ve knocked down all the walls, they’ve taken all the stinging nettles, they take all the sh** and whoever’s second, which is damn near to first, waltzes through and has an easy life.” [from Many Years From Now]

.

Now, obviously, John’s leadership wasn’t absolute — Paul was more interested in the studio, even in the early days; George Martin saw that, and he and Paul handled that more and more as the music grew more complex. And as they all aged, John’s two years meant less. But once again, it’s a change from the initial state, which was John in charge (whatever that meant, and J/P/G/R were the only ones who really knew what it meant).

.

In fact, the whole issue between John and Paul, according to John, was that Paul attempted to change the relative power within the band, after Brian’s death. If you don’t believe that — if you believe that John and Paul were always co-leaders — then you’re disagreeing with both what Paul has said, generally, and what John said broke up the band. That’s kind of a big thing to disagree with.

.

In every creative partnership there has to be a rough agreement, often unspoken, on how the power is divided. “You handle this, I’ll handle that, and in case of a disagreement, we’ll do x.” In the case of me and my writing partner, I made the final decision on edits before we sent pieces to The New Yorker or Saturday Night Live. Could my partner have done that? Sure. Did he feel I was better at it? Clearly. If I’d been knocked senseless before we sent something out, would anybody have been able to tell that he, and not I, had made the final calls on a piece? Probably not. But that was the arrangement that we settled upon. It didn’t make him lesser; in fact, sometimes it gave him more leeway for creative control on a piece, because I was busy thinking about “real world” stuff. And it should be said that especially after you work together for a long time, a sort of “third mind” is created. And also, if the piece was “his” — meaning that he had come up with the idea and written the majority of it, I would defer to him if he asked. But for reasons of both personality (I’m more aggressive) and efficiency, I was the boss, in that limited way.

.

I’ve always gotten the strong indication that, certainly before Pepper, Lennon was the boss inside the Beatles, in a similar limited way, and everything I’ve ever read from either guy suggests that was the case. And it was Paul’s understandably outgrowing that arrangement that caused friction. That’s a logical reading, backed up by a lot of data…and, as I’ve said, my own experience. So I’m cool with it.

.

What I find fascinating is the fans who — and I think this is a recent phenomenon — who AREN’T cool with it. Who insist that “The co-leaders of the Beatles were always John and Paul” when *John and Paul themselves said* that wasn’t how it worked. The “co-leadership” idea is clearly standing in for something; it’s important to these fans that the narrative be changed in this precise way, and I’d like to hear why it matters to them. The historical record is as clear on this point as it can be…but that’s unsatisfying to them. They need the story to be different. Why is worth asking.

.

Brian is a bit of a different situation. Some sources suggest that Lennon and Epstein were the braintrust — the guys who really wanted to conquer the world, saw eye-to-eye completely, and saw that it could be done — in the first period of the group. I think by 1964 it’s clear that Paul (and George and Ringo, too) all had strong opinions and veto power. But I don’t think it’s a stretch to suggest that Brian was “co-leading” the Beatles from 1961 to Pepper. He was making the deals and dates — ie, he was determining when they performed, where, and for whom; he was picking collaborators; he was fixing problems. Remember, they were all young, and Brian was significantly older than even John and Ringo. Of course they would defer to him.

.

It makes sense to me that Epstein was leading the group in a business sense; Lennon was setting the tone within the group; and Paul was collaborating with George Martin during the recording process, especially after ’65. That’s how I took @Michael’s comment — that Epstein’s addiction left the Beatles rudderless as a business entity, which I think it did. I don’t think John or Paul were doing any business stuff then; John had no taste or aptitude for it, and after the world was conquered, absented himself entirely. Paul turned out to be quite astute, he wasn’t doing it in November ’66 (at the ripe old age of 24).

Good points, Michael. The one thing I question is how much it was McCartney’s “understandably outgrowing” Lennon’s being the boss that caused the shift in roles. Some of that was in play, for sure, but I think that if Lennon had been as strongly invested in the band as before, McCartney could have been content to go on being the de facto second in command. My take is that when Lennon got less interested in pushing and giving all his energy to the Beatles, McCartney freaked out and tried to “fix” things by supplying the lack. And Lennon resented (and might have feared/been jealous of) all that energy, and then . . . . we’ve followed that sequence out repeatedly in the threads on the breakup.

.

I believe McCartney when he says he “enjoyed being second” in the band. As pushy as he could be, I think he was hurt, grieved, and frightened when Lennon seemed to check out of his leadership role.

I was a major John fan most of sixties and part of the seventies and began amassing a major mag, newspaper, etc. collection on them in 69. All earlier information noted there was no question that John was Chief Beatle pre 67 and I have seen video interviews of all of them being asked who was leader and they all said John. It was, however, John and George’s decisions to quit touring in 66 and Paul was much more comfortable in the studio which gave Paul the advantage. Also, John did his movie role, but Paul’s 66 movie contribution was simply a soundtrack and a song aided by George Martin. Likewise, George chose to go to India a few months when part of pepper recorded and study sitar. Paul stepped in to keep them going and current as they became a studio band because the late sixties were evolving rapidly. Later it appeared that John and George wanted to step back and pursue their own interests and obligations but increasingly resented Paul for his ideas and quickly blamed him when the failed, as with the movie MMT though album/ep was a big success and let it be. John and George seemed to want their cake and eat it to.

Likewise, all Beatles took off from recording and followed George to India though it turned into a fruitful song writing time. Yes, it was indeed by all my old mag articles after touring ended that John’s role as Chief Beatle ended and the decision to become a studio band along with drug excesses of the group changed group dynamics forever.

Paul’s biggest mistake was dragging an increasingly resentful dysfunctional bunch along although who knows why he did it but it appears he felt they could achieve more creative greatness. They had completed their record contract in late 66 and he should have let them fold and all go solo or join other bands. John said he and George wanted to quit,….but didn’t have the guts, Paul should have quit in 66 when others pulling apart, before they started resenting him. Then the other Beatles and many Beatles fans even today would not blame paul for the later group going south. Paul could have done a lesser version of sgt pepper on his own and played what instruments could as did on McCartney 1 and McCartney 2 and John and George could have followed Clapton and Dylan in their bands while ringo played drums with other acts. I preferred the later Beatles albums for years but we’re not worth the extreme unhappiness of all of them, as John and George did nothing but whine about their unhappiness then. Now, the Beatles legacy if ended in 66 would have forever been that of a pop rock n roll group playing to screaming girls rather than the greatest progressive rock group of the late sixties.

No question John was Chief beatle in 66 and earlier and it was when he abdicated his role that trouble began. All wanted John to continue to be Chief Beatle but for one thing he couldn’t see past rock n roll and folk rock and a little psychedelica influenced music. It was in 67 when John musically and lyrically began to fracture as had to be pushed by Paul to even produce enough for pepper.

I want to add that I completely agree with Nancy about later Paul and John role and John’s abdication of leadership and interest in Beatles……Paul lyrics….you left me standing there, a long, long time ago and when you told me, you didn’t need me any more, well all I did was…..go down and cry….die. Paul literally gave his all to try to save the later Beatles and was deeply hurt at John and has been since by all fan and critic dissers and blamers but, though he saved their later music and legacy, it cost him his own credibility and legacy a long time which he slowly and painfully had to build back….wading through all the bossy, conceited Paul, second fiddle to genius John, jealous Paul and repressor to George stereotypes.

Paul reminds me of the oldest child having to step into parent role due to parent abdication and younger siblings and hated and resentful of substitute parent, as wanted the deficient abdicated real parent. It was an extremely toxic, dysfunctional situation he as a young man wanted to keep going as he saw the musical potential of Beatles and the group was all he knew as a teen forward so he didn’t have wisdom to let them go in 1966 when he should have. I’ve often thought of a no later Beatles probability, especially as read so much then and since about the later increasingly toxic Beatles and it would have served other Beatles and resentful fans then and now right to have just younger Beatles as the legacy, the mop tops playing pop rock n roll to screaming teeny boppers, quitting at revolver that hinted of later great possibilities. I worked as a backup to a boss like passive aggressive, abdicating his role late beatle John and well understood the bashing and blame of the secondary receiver of all the scapegoating and I gave little patience for it from my own experiences.

Great points, Nancy! I agree that Paul didn’t mind being labeled a second-in-command; I think John was more a gang leader than a band leader, and I think Paul was just enough of a control freak to want his creative vision borne out and want everyone to see that his way was the correct way and to be super-annoying about it, not that he wanted to lead the Beatles per se, because I don’t think he could ever have led them as a gang. And I think he had to know he could never have led them as a gang — only witness everyone falling in line behind John over Klein. Which was not a good leadership decision on John’s part at all, though it was a power decision. But following a mentally/chemically compromised “leader” wasn’t a good idea any longer.

.

MG, you say “it’s a change from the initial state, which was John in charge (whatever that meant, and J/P/G/R were the only ones who really knew what it meant).” I think that’s at the crux of the matter; people are trying to decide what that meant. As you noted, John and Paul each had different roles within the group. What John and Paul said changed depending on who was saying and and when they said it. I.e., they have the quotes you mentioned, and they also told journalists that there was no boss of the Beatles and that whoever shouted the loudest usually got their way, and John shouted the loudest; and John complains about being forced by Paul and Brian into suits and forced to be clean and presentable; John crawls under tables and hides at press conferences. Stuff like that makes it seem the question of his undisputed leadership might possibly merit a reexamination.

.

I also think a lot of the reexamination that’s been going on recently is a negative reaction to the argument some have brought out to explain why John destroyed everything they’d all built and why he was utterly justified — i.e., “well, John was the leader and he started the Beatles and that sneaky Paul was sneakily trying to undermine him and take control of the band.” It absolves John of any ultimate assholery because he was the leader and could tear down his own sandbox, and it gives everyone a good reason to think his treatment of Paul was right and just based on Paul being sneaky and bad.

.

I was reminded recently of John Green’s quote from John Lennon that he’d never forgive Paul for taking away the job of finally ending of the Beatles from him, even though it was a distasteful job, because it was Lennon’s job as the person who’d started the band. This seems very in line with other bits of Beatle history I’ve read regarding John and the undesirable Beatle duties. But then Green had also convinced John that the tarot cards showed that Paul and Linda were on the verge of divorce and that Paul only showed up to visit so he could gloat over how horrible John’s life was, so his reliability is called into question for me.

.

(Be gentle with me, please, these are just possibilities and my perspective. Maybe I don’t really care enough about Beatle leadership, so. A male Beatle-fan my age told me “it’s a guy thing, you wouldn’t understand” but I’ve seen women get really heated over the issue also. It transcends gender.)

Really interesting, Kristy. I think there was also a real shift in what “leadership” in the band meant over the years. Lennon was the inspirational force behind the band at the outset; he had the “cannon charge” that Michael B. has written about here, and which McCartney described as kicking down fences so the others could follow. I think the problems for him came once the Beatles were on top, because where can you go from there? His visionary force doesn’t seem to have had enough to push against, so to speak.

.

McCartney is a self-described “keeny” who likes to work hard, and is more a realist than a visionary. So in some ways he was better suited to life on top than Lennon was, because he wasn’t worried about the next big thing, or feeling unsatisfied with the big thing — he was happy to work on the big thing, if you see what I mean.

@Nancy, I think that Lennon really didn’t have any idea what to do after the Beatles stopped being a touring band. It didn’t fit with what a rock band was, or was for, in his mind. McCartney, on the other hand, had the skills and interests to lead a studio-only group. I suspect that if Lennon had said in 1967, “We’re doing THIS, and fall in line” the others probably would’ve. But we must remember that there’d never been a band like The Beatles, and they’d never just kept existing without live performance. Then Paul came in with his ideas, and they all fell into line. That must’ve been a great relief for John initially.

@Kristy, of course I’ll be “gentle” — sorry you have to ask me. I haven’t been as gentle with our commenters in the last six months, partly because I’m working so hard and partly because we keep talking about the same topics — but ungentle is not how I wish to be, and I’m trying to figure out how to move forward with my involvement here. It may be time for me to lurk.

.

Gendered or not, I do think there is something fundamental about “leadership,” and either you understand it or you don’t. It’s not telling people what to do, or thinking the sun shines out of your behind — kinda the opposite of both of those things. It’s more a personality type, probably an overvalued one — you can’t have a good leader without a good #2, or good gang members; it takes a village, and everybody has their part to play. The Beatles would’ve been infinitely less without McCartney. Or Harrison or Starr. But I don’t think they would’ve happened at all without Lennon, and to some degree Epstein.

.

I’ve been leading creative endeavors since I was 16 or so and to reach a certain level of quality, you need a boss. You just do. It’s like saying you need sunlight for a tree to grow; it’s simply how things work, it’s not personal. Even something as loosey-goosey as HD needed a boss to get going; we talked for a month, with me waiting to see if someone else would take the lead, and then I was like, “Fuck it, I’m doing it.” Then, you see if people will follow — do they like your vision? Do they like you personally? Are you fair? Are you kind? Do you share? HD needed someone who would decide what it looked like, and who determined, through lots of posting, what it would be and not be. The idea that creative stuff just “happens” is the hallmark of the dilettante. Being a expert, professional creative person is nothing BUT decisions, and much of the time democracy is simply too unwieldy and time-consuming to be practical.

.

So every creative endeavor has to have a manner of functioning that allows decisions to get made quickly and well, while at the same time not being so repressive that talented people won’t join or stay. When John said that we should all give him credit for letting Paul into the band, that’s real. Most people as talented as John was, at age 17, would not have accepted a rival. Because that’s what Paul was at that point: a rival. Only later did he become a collaborator or friend.

.

So, yay John Lennon, Leader of the Beatles. But people who say that John was utterly justified to end the group are idiots; that’s not wise leadership. Leadership is something you earn, and re-earn constantly. The moment that Lennon returned from India, it was clear that he was out for himself, and not the group, and the other three’s rights and responsibilities grew as his were given up. They could’ve been called John Lennon and His Fabulous Beatles, and by 1970 it wasn’t his group. By 1970, they were a band of equals, or two and a half equals; they were the most equal any band has ever been, and they’d been mostly democratic up until Klein. To arbitrarily end the group wasn’t John’s call, and the idea animating that is YOKO’s idea — that he was the only genius, he was the only artist, they were talents of a lesser order or his minions — and that’s absurd. Anyone talking like that in 2020 is not a serious person. I’d go so far as to revoke their Beatles fandom; they’re Lennon fans. Yoko is the opposite of a leader; “she looks at men as assistants” — that’s the opposite of leadership in a creative endeavor. Her talent expresses itself as a solo act; different beast entirely.

.

One quick point: Paul’s sneakiness, his “two-facedness”, his being “the world’s greatest P.R. man” — all of this is Paul’s “hero” persona. His perfectionist people-pleasing. He wants to avoid conflict and be liked, and also (because he’s very smart and determined) get his own way. John’s style — the rebel who’s constantly testing people’s love — isn’t more honest. It’s simply another style of trying to control everything and get what you want. But I have seen many families splinter along that axis.

Appreciate the comment above in this discussion as provides different angles, but I don’t think Paul was intentionally trying to be super annoying or forcing his ideas upon the others. I just think he was doing what had done before, perfecting recordings, studio work but as John and George stepped back at the same time, Paul realized correctly the group would fall apart without album ideas, songs and projects. He was naturally a hyperactive, possibly a hyper manic prolific workaholic and perfectionist and the other three, including ringo all pulled back when he stepped forward around time of pepper. When the others were interested enough during early Beatles and under heavy record contract to produce singles and albums, and toured, all were more involved. When all of the others were interested and involved, the group and it’s product functioned smoothly. When the other three stepped back and pursued their own interest, the group started unwinding.

I have for decades continue to see the various blame Paul stuff in later Beatles assessments but we can all thank him for all for the later Beatles music we like and the late Beatles becoming the leading progressive rock group of the late sixties because from all of my reading, John wasn’t the only one who checked out after 66. George had long absence learning sitar rather than improving his guitar skills and Paul had to play George’s parts on Beatles songs, George came to pepper sessions late with only one new song, Beatles stopped and followed George to India later though George had a few other incomplete songs in reserve and ringo played chess with mal during pepper sessions.