- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

Michael Tomasky, former editor of The American Prospect and The Guardian America, is getting into the Beatles’ 50th anniversary racket. His ebook, Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!: The Beatles and America, Then and Now, has just been released; in it, he puts forward the idea that the Fabs were “the sound of freedom,” catalysts for (and participants in) the vast cultural opening that occurred in the West from 1964 onward. His overview addresses everything from race relations to Ringo’s revolutionary use of the hi-hat.

A longtime political columnist, Tomasky writes a thrice-weekly column for The Daily Beast and contributes on a regular basis to The New York Review of Books. He is also the editor of Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, a quarterly progressive journal based in Washington. He lives outside Washington with his wife and daughter and brand new, rather huge dog.

Tomasky was kind enough to send us copies of his ebook and, ungrateful reprobates that we are, we peppered him with questions. His answers are below. — MG

How important do you think Brian Epstein and George Martin were to the Beatles’ success?

Obviously, they were enormously important, in all the ways we all know. None of this could have happened without them. I didn’t discuss them much in my book because I wasn’t telling that kind of biographical story. I was doing a sort of cultural history of the band’s impact. Also I was trying to avoid most of the super-well-known story lines and (hopefully) write something a little more original.

What aspects of the Beatles’ work do you hear in popular music today?

I have to be honest and say that I don’t listen to that much new music. I listen to some of the Sirius/XM stations that play new music when I’m in the car. So I’m far from expert. But I would say the following. Rock today seems to me to be not all that different from rock music of 1969 or 1974. Same basic idea. It’s the same way modern art didn’t really change in any deeply qualitative way from the 1910s to the 1950s. You had many geniuses in that time frame, of course, and they had many approaches, so I’m not devaluing the art of 1945 or the music of today by any stretch of the imagination. A lot of the music I hear on these stations is very good and would’ve really fired my loins when I was 20. I’m just saying that, once Malevich has painted an all-white canvas or the Beatles have made the White Album and the Stones have made Exile, there are only so many remaining permutations of form that are possible.

I’d add: Any two-guitar/bass/drums band is on some level imitating the Beatles. They invented that.

Which musicians today do you think are carrying on the experimentation and creativity you find in the Beatles’ work?

I’m sorry, I really don’t know. I like Arcade Fire pretty well. They’re not Beatles-esque, really, but I’d rate them highly on the experimentation/creativity fronts.

Why is it that the divide in political positions in the U.S. “no longer tracks very much with musical taste”?

Because rock ‘n’ roll took ownership of popular culture. One of the things I try to bring out in the book is the fact that back then—and this became more true by ‘67 and ‘68 than in ‘64, but was still true to some extent in ‘64—if you liked this kind of music, you probably had a certain set of broader attitudes. How could you adore Sgt. Pepper and be a conservative in 1967? Sgt. Pepper told people: take drugs, fuck, break rules, run away from home. What kind of conservative could possibly endorse that?

But at a certain point (see next question), rock ‘n’ roll became so all-powerful and universal that the relationship between the music and the larger anti-authority values in whose name the music was made ceased to be. Something that becomes that commercially potent can’t also be insurgent, I suppose. The contradiction becomes unsustainable at some point.

When do you think that change occurred?

I don’t know, but I know vividly when I first realized it. It was 1994, and I was covering New York politics, and George Pataki was the Republican candidate against Mario Cuomo. And there was some article in the Times where Pataki said he was a huge Stones fan. And I thought, what is he talking about? Doesn’t he understand that the Stones despise everything he stands for? He was conservative, in those days, although of course by the standards of these loons today, he was practically Nelson Rockefeller.

So I puzzled: Is he just that dumb, that he doesn’t know that the Stones stood for everything he opposed? Or does he know it and choose to ignore it? After being pissed off about this for a week or so, I finally thought well, “Brown Sugar” feels good, and I suppose it does the same thing to George Pataki’s insides that it does to mine. I confess it still doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. But I guess most people just don’t even think about music on this level—if they like it, they like it. I like all kinds of square music. Burt Bacharach, I suppose some would call square.

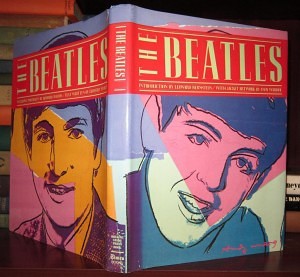

In the book you refer twice to a quote from Leonard Bernstein’s introduction to Geoffrey Stokes’ 1979 book on the Beatles, in which Bernstein praises “the ineluctable beat, the flawless intonation, the utterly fresh lyrics, the Schubert-like flow of musical invention, and the fuck-you

coolness of these Four Horsemen of Our Apocalypse.” You take some issue with the “Four Horsemen” part of that quote, but you do acknowledge how central the Beatles were to the changes in society that began in the 1960s. How would you briefly sum up the Beatles’ role in changing society?

Briefly?! They started the personal-liberation earthquake that was the Sixties. Period.

I didn’t like that Bernstein quote because it was just too overheated. I find a lot of writing about great music really overheated. One reader told me that one thing he loved about my book was that I didn’t do that, backed off the multiple-adjective accelerator. That was conscious, and I was very pleased that someone noticed.

In the epilogue you say that “Lennon was a political figure, and I don’t mean from his early 70s radical-chic days. From the start.” What do you mean by “political figure” here?

As a couple of my above answers suggest, I see a very clear relationship between a type of music and its political implications. The Beatles were apolitical on the surface, especially in the early days, but to me, the politics of it were obvious. They said: live, experience joy, be in the moment, leave tomorrow for tomorrow. Such a posture has obvious political shadings.

How different do you think Lennon was from the other Beatles in this respect?

In this particular respect, not very! I’m talking about the band, the message that emanated out from the group as a whole. Except that I guess Lennon was the most aggressively anti-authority from the start, somehow. I have a line in the book where I’m writing about how they must have come across to Americans on Sullivan, and I write Lennon “looked like he was auditioning the audience,” which I think isn’t bad. Then a guy on Irish radio was interviewing me Wednesday night and he quoted Billy Joel saying that when he saw Lennon on Sullivan, Lennon just looked like he was saying “fuck you” to everyone, and Joel said it was that look on Lennon’s face that made him want to be a rock musician. So he just exuded that f-you thing in a way the others didn’t.

What are a few more Beatles songs that you think are especially revolutionary and interesting, in terms of musical structure and texture?

Start with the boringly obvious: “A Day in the Life.” “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

Early: “It Won’t Be Long,” which I rhapsodize about at length in the book; “There’s a Place”; “Hold Me Tight”; “Don’t Bother Me.” All of these mostly because of their chord structures and relationship between melody and chords.

Mid-period: “The Word”; “For No One”; “And Your Bird Can Sing”; “If I Needed Someone”; “Getting Better”; “Fixing a Hole”; “Lucy in the Sky.”

Late: “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”; “Dear Prudence”; “Blackbird”; “It’s Only a Northern Song”; “You Never Give Me Your Money”; “Oh! Darling”; “Because.”

These are not necessarily what I’d name as their greatest songs, or even my personal favorites, although several of them are. I’m answering the specific question put to me as a person who taught himself guitar and piano largely in order to learn to play these songs!

You can buy Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!: The Beatles and America, Then and Now, here.

Hey Dullblog thanks Michael Tomasky for responding to our questions, and look forward to hearing our readers’ thoughts about his responses.

Overheated quote:

“Any two-guitar/bass/drums band is on some level imitating the Beatles. They invented that.”

Jesus! No they didn’t. They certainly improved on the form, but Gene Vincent, Carl Perkins, The Crickets, and a thousand others were doing the two-guitar/bass/drums group thing before 1963.

Also, Mr. Tomasky’s thoughts on the White Album and Exile reminded me of Homer Simpson’s remark:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLqfXlIq6RE

“Any two-Rickenbacker/Gretsch guitar, Rickenbacker/Hofner bass, Ludwig drums band with three-part harmonies playing power pop is on some level imitating the Beatles. They invented that.”

FIFY.

I’m well aware of Hey Dullblog’s goal to include more George/Ringo assessments, and I approve. But I’ll be damned now that this blog’s more stealthy campaign also has me rethinking the standing of “The Word” in the Beatles’ pantheon, with Tomasky calling out its significance and @hologram sam’s prior posting the MJSokes drum-along video. I guess I’ve always let the relative vapidity of the lyrics obscure what a tight little ditty it is.