- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

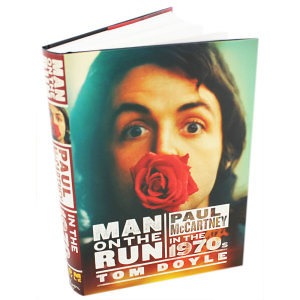

At this late date, it’s a rare book that fundamentally redefines what I think of a Beatle and his work. But after reading Tom Doyle’s Man on the Run, I’m hearing Paul McCartney’s Seventies music in a whole new way — not as tuneful, inoffensive AOR, or bargain-bin Beatles, but as a legitimate second act — a bit like Dylan after the motorcycle crash.

Doyle is just the right man for this job; a longtime contributor to the Beatles-crazy UK music mags MOJO and Q, the spine of Man on the Run was formed by a series of interviews he did with McCartney over the last several years. Doyle has an ability to tease Paul a bit, knock him off his spot, and this allows him to penetrate Paul’s persona a bit.

“When stability becomes a habit,” B.K.S. Iyengar wrote, “maturity comes and clarity follows.” Man on the Run shows McCartney painfully building a new stability out of the ruins of the Beatles, achieving a kind of own-two-feet maturity during the Wings Over America tour, then ending the Seventies with the clear knowledge that he was fundamentally more than just an ex-Beatle. You can hear this all through McCartney II, where he’s finally comfortable enough to experiment in public again.

Nancy took issue with the above, and it’s only right that she have her say: “I wouldn’t say that McCartney entered the 80s with stability, feeling he was ‘fundamentally more than just an ex-Beatle.’ Maybe, if Lennon hadn’t been murdered, that could have happened. But I think that Lennon’s death scrambled McCartney emotionally and artistically. Constantly being compared with Lennon, to his detriment, sure undercut whatever stability he’d achieved. The 80s are the period when I think he did his worst work. I see Doyle’s book as highlighting McCartney’s resilience. I’d say that McCartney isn’t consistently stable or mature , but he is consistently The Unsinkable Paul McCartney, always willing to get back up and try again.”

I can’t say I disagree with that, either. Perhaps Tom Doyle has another Macca book in him?

The author was nice enough to answer a few questions that Nancy and I lobbed his way. We’ve reprinted them below.

•••

We loved the detail of the old ripped couch where the kittens would hide. In your conversations with Paul, what sense did you get of what enabled him and Linda to have such a durable marriage? And why was it so important to him to have Linda and the children with him on the road?

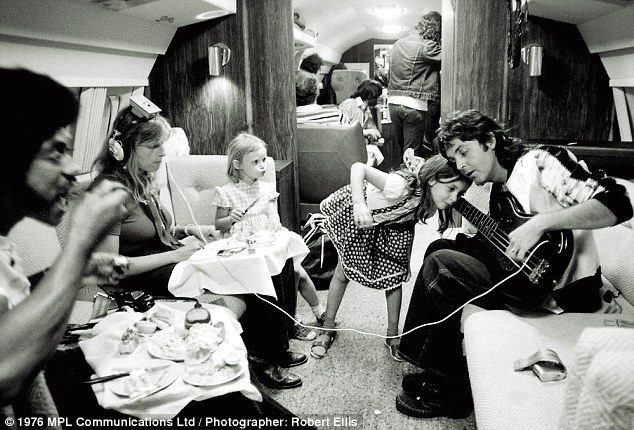

I think their durable marriage can be put down to them being determined to maintain a sense of normality, in spite of the highly unusual circumstances of their family life. There’s a great pic of them all together having dinner in a lounge area from ’76 – Linda eating from a tray on her knee, Paul playing bass, while the kids sit around them. Only on closer inspection do you realize that they’re actually on their private jet, in the middle of the Wings Over America tour. I think that says a lot.

“OK Steila, that’s a ‘time-out’! Into the overhead compartment!”

It was really important for Paul to have Linda and the children on the road, to cure what you might call the loneliness of the long distance runner. Being a solo artist/band leader can be a very isolating business. The “family on the run” thing was massively important, for him maintaining stability. Having said that, Paul did admit to me that tour life sometimes wore them down, causing arguments. “It was a big love affair,” he said. “But it wasn’t perfect.”

In the introduction, you note that Paul has a tendency to hold reporters at a distance; he wants to maintain a sense of privacy — a public/personal line that he does not cross. How satisfied are you that you saw the “real” Paul McCartney? How were you able to maintain his trust, despite the feeling you got at times that you were pushing him to talk about something he didn’t want to?

I don’t think any interviewer can say, walking away from the artificial set-up of an interview, to have really seen the “real” Paul. But I think, without being immodest hopefully, that I got closer than most. I think being cheeky and Scottish and not unwilling to have a laugh with him/gently poke fun/really push him at different points, helped paint a portrait of him that is (one hopes) way beyond the usual PR spiel. If I managed to maintain his trust, it was just through being earthy and unfazed by his fame.

Even when I knew I’d pressed him on a point, I’d move on quite lightly. Despite some of the subject matter, these weren’t “heavy”, probing, combative interviews. I’m sure he’d have clammed up pretty quickly if they’d seemed that way. But I feel the chatty, lightsome approach allows you to venture into darker territory sometimes.

You mention that Paul seemed surprised when you said that his public persona might give him a screen to hide behind. Do you think that surprise came from his never having thought about it, or from being startled that you saw it or brought it up? How much do you think he consciously crafts his public persona?

Analyze this.

No — I think his surprise was genuine. As he states breezily in the introduction, “I’m the world’s worst analyst of me.” I believe that’s right and it’s this lack of self-analysis that keeps him sane. Trying to imagine how others see us is a pretty impossible task, and it must be unthinkably worse for a legendary figure like McCartney.

So no, I don’t think he consciously crafts his public persona, but like all of us, you try to present your best side to the world. As a result, the Macca we see isn’t the one who gets grumpy or annoyed and is generally a chipper figure.

Why do you think Paul was often treated harshly by critics, especially in the 70s and 80s? Which of his post-Beatles work do you think will last?

I think he was unfairly treated for a couple of reasons. Firstly, he was presented as supremely confident, to the point of slight smugness, in the film Let It Be. Secondly, he was then seen to have “quit” the band. So I think the critics’ knives were sharpened for his next records, and were seen as lacking when held up against the golden light of The Beatles.

Also, it was the era of heavy rock, heavy statements, and so he was seen as lightsome — which in fairness, a lot of his ‘70s stuff was. But the reissue program of his ‘70s albums is certainly painting them in a different light; I think Ram, Band On The Run and even Venus And Mars will be viewed as key albums of that decade.

Why do you think John Lennon attracts a level of devotion among fans and critics that Paul McCartney usually doesn’t? How much do you think this difference bothers him?

Well, John of course is always viewed as having been the “arty” Beatle, which obviously attracts more reverence. Then there are the horrible circumstances of his death, which almost canonized him. I’m a massive, massive Lennon fan, but it’s often forgotten how many ropey albums he made in the ‘70s (Sometime in New York City, Mind Games).

I think Lennon’s towering reputation does bother McCartney a bit, particularly when they were once level players and close friends. I think this is where certain strange moves on McCartney’s part come in, like the reversal of the credits of key Lennon/McCartney songs (for Back In The US) to highlight who had the greater contribution to the composition. Or McCartney’s forensic picking apart of the songs in Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now. But as I point out in Man on the Run, I think really this is keeping alive the competition between the two, which surely would have carried on – and been fanned – by Lennon had he lived.

Do you think the way the Beatles ended contributed to Wings’ shifting lineups? Was Paul afraid that working with genuine peers would result in recriminations and legal hassles?

Wings, Nashville, 1974: A combustible mixture.

I think that’s highly likely. He was sorely burned by the experience of The Beatles court case, and obviously less than keen to commit as fully, in contractual terms, to the players in Wings. This is spotlit really by the period in ’74, when the second line-up of Wings travel to Tennessee to work up the new band and there are fallouts about contracts. The band had expected to be “signed” during this trip, but there were arguments in rehearsals, and McCartney quickly cooled on the idea of legally locking this band in. Shrewdly so, as it turned out.

Did you get to see Paul’s Japanese prison diary from 1980? Has anyone? Are there any plans to release that?

What eBay is made for.

I haven’t seen it, no. I imagine what’s in [the diary] is pretty much what he’s said in interviews, including mine, about the experience. The final Wings guitarist Laurence Juber did tell me he’d read it just after Paul had written it and said it was very moving and personal.

Would you call Paul a classic British eccentric? Why do you think people are so unable/unwilling to see this part of him, in favor of the ‘control freak’/’PR man’?

Yeah, I’d say he’s pretty much a classic British eccentric. But then most musicians, even the ones who seem super straight, are gently bonkers. I think people form concrete opinions about stars, which they’re unwilling to have anyone chip away at.

After writing this book about Paul, how do you see John, George or Ringo differently?

I think I now view John – also after having interviewed Yoko three times, including once in the kitchen at the Dakota – as someone who was clearly a firework ricocheting off the walls, and a deeply sensitive man, but also very very difficult at times. George I suppose was steelier in the ‘70s than his peaceable image suggests. Ringo meanwhile was supremely laidback, it seems, in contrast to the comedy grump he has now become.

What surprised you the most? What aspects of Paul did you not expect?

This eccentric side of him. For me, this held the key to a lot of his more baffling moves such as “Mary Had A Little Lamb,” or thinking he could take half a pound of dope into Japan in 1980. This was the side to him that I wanted to write about in the book. He really did (and still does) make decisions based on complete whims, for better or for worse.

Do you think John and Paul would’ve written together in the 80s?

I’m sure they would have done – Live Aid would surely have brought a Beatles reunion. I suspect it would have taken them longer to make a new Beatles album (all involved were afraid of tarnishing the Fabs’ reputation). But I suspect it would have happened, probably in the ‘90s and been pretty damn good. Let’s face it, “Free As A Bird” and “Real Love” were pretty damn good.

Has Paul commented on your book?

He hasn’t, but he did read the synopsis because we wanted to clear the Linda McCartney shot of him with the rose in his mouth (from the Red Rose Speedway session) for the cover of the UK edition. He allowed us to use it, so I took that as some kind of gentle endorsement.

He hasn’t, but he did read the synopsis because we wanted to clear the Linda McCartney shot of him with the rose in his mouth (from the Red Rose Speedway session) for the cover of the UK edition. He allowed us to use it, so I took that as some kind of gentle endorsement.

Besides Man on the Run, what’s your own essential McCartney library?

I really enjoyed Peter Ames Carlin’s McCartney: A Life, Barry Miles’s McCartney “autobiography” Many Years From Now and a strange little paperback by George Tremlett from 1975, The Paul McCartney Story, which is long out of print but contained lots of interesting details. Having read dozens of McCartney books, I was very happy to feel I could write a worthwhile addition to the library, and hopefully I have.

Sorry but where’s the interview? There’s no text visible here to read??

Wha-? That’s weird.

If this happens to anybody else, just reload it, and it should work. I’m going to check into it.

Thank you Michael and Nancy for this great interview. I loved Man on the Run. It would be great if Doyle wrote another book about the 80’s and perhaps each decade up to the present. I love Doyle’s writing style and his honesty. I agree with his statement that some people refuse to see McCartney’s eccentricity. It’s amazing to me because from the beginning his eccentricity always seemed the biggest and most obvious part of his personality. For me everything he has done and does, is filtered through this view of him as an eccentric! Also about the competition between Lennon and McCartney, I agree of course with Doyle’s opinion but I want to add my memory of a 1972 issue of a music mag called Hit Parader, that contained a very interesting interview with Lennon where he dissected every Lennon/McCartney song and discussed who contributed what and the percentage of that contribution. So in my memory Lennon’s dissection of the songs pre dates McCartney’s by about 20 years. Indeed their competition was a huge part of their relationship and an interesting one.

“Eccentric” is putting it mildly! I appreciate the way Doyle brings out McCartney’s deep strangeness. Lennon was such an eloquent, persuasive interview subject that he got the “Paul is a square” belief deeply embedded in the music press in the 1970s, and it’s never gone away. And McCartney IS square, in certain ways: he loves domestic life, fatherhood, and the countryside. But he’s also profoundly odd. Doyle gets at that combination in a way that nobody else has, IMO.

Agreed, Nancy.

It’s amazing how emotionally and intellectually stunted rock culture was in the ’70s (and is today). In this peculiar world, loving domestic life, fatherhood, and the countryside were things to be ashamed of… as opposed to what they actually are: the natural interests of a parent-aged person! Lennon eventually caught up to McCartney in this regard, and it’s why I agree so strongly with Doyle that they would’ve written together. Lennon loved the countryside too (Scotland particularly), and it’s simply impossible to think these shared non-musical interests wouldn’t have built a new bridge between the men.

it’s simply impossible to think these shared non-musical interests wouldn’t have built a new bridge between the men.

If John had lived, would he have been forced to choose between Yoko and Paul? How interested was she in bridges?

IMHO, yes, @Sam.

I agree. Lennon and McCartney were soulmates. The problem was, Lennon needed one thing to be “It,” the answer, and everything else had to be crap. He was too much a person of extremes and absolutes, in every aspect of his life, to make room for Yoko without abandoning Paul. And Yoko, of course, absolutely encouraged that way of thinking and egged Lennon on in every respect, until he was so isolated—from McCartney, from England, from himself—that he was, for much of the Seventies, a shell, and completely dependent on her. It’s hard to think that, had Lennon lived, he would have been able to sustain through the 80s, the 90s, the 00s the same level of distance and coldness toward his real other half.

There’s another component to the songwriting credits issue that I feel has been overlooked. In a 2001 interview with Rolling Stone, Paul told Anthony DeCurtis that he asked Yoko in 1996, while prepping Anthology 2, if they could switch the Lennon-McCartney names on “Yesterday” only. “This is when Linda and I were going through our real horror times,” he added, when Linda was battling breast cancer. Yoko said no. Then Linda also called Yoko and asked her to do it, as a personal favor, and Yoko said no again. Paul said it wasn’t just Yoko’s refusal to consider it that soured their relationship, but “the fact that Linda rang her personally during the height of her chemo shit and asked her, and Yoko said, ‘That’s never going to happen.'”

In December 1997, right around the time Linda was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer, Yoko gave the infamous BBC interview where she said Paul was Salieri to John’s Mozart, a remark which clearly upset Paul (he mentions it in the DeCurtis interview as well) at what was already a terrible time in his life. Yoko, of course, couldn’t know the details of that, but to Paul it must’ve seemed like rubbing salt in his wounds. In her tribute to Linda written for Rolling Stone, Yoko wrote that she last spoke to Linda in January 1998, but not about the content of the conversation. So close in time to the Salieri comment, and considering Linda’s protectiveness of Paul, I don’t imagine it was a a necessarily friendly chat. Paul pointedly did not invite Yoko to Linda’s memorial service, stating that it was because they were not friends.

Clearly, the songwriting credits issue bothers Paul on its own, but circa 1996 it seems to have gotten intertwined along with his feelings about how Yoko treated Linda when she was ill. That’s not to say anyone was right or wrong (I don’t think Yoko was obliged to agree to the chance just because Linda was sick and asked for a favor) but it does show that Paul is human. Like most humans, sometimes what an issue appears to be about isn’t always, or totally, what it’s really about.

That’s interesting context, Rose. Paul’s gotten a lot of bad press about wanting to switch the songwriting credits, but it’s also worth asking why Yoko is so set against ever allowing that. She seems determined to present Paul as Salieri despite all evidence to the contrary.

And that goes back, IMO, to the comments Hologram Sam, Michael G, and Michael made about what might have happened between Lennon and McCartney post-1980 if Lennon had lived. From what I’ve read, the one person who seemed consistently against Lennon and McCartney working together after the breakup was Yoko. Linda encouraged Paul to pursue it. As has been brought out before on this blog, John (and May Pang) were invited to come to New Orleans for the “Venus and Mars” sessions in 1975, and it looked likely: except that that was exactly when Yoko called John and he went back to her. Maybe that was coincidence, but it’s suggestive, especially given some of her other actions (like not telling John that Paul had called during the “Double Fantasy” sessions). Sure seems like she was threatened by the idea of their playing or writing music together.

Lennon said that the only two people he ever worked with as “full artistic partners” were McCartney and Ono, but those partnerships looked very different. Apart from the early experimental work (“Two Virgins,” “Life with the Lions,” “The Wedding Album”) John and Yoko didn’t work closely together on music. From their “Plastic Ono Band” albums to “Double Fantasy,” what they do looks very side-by-side-but-not-touching. They didn’t harmonize, either vocally or musically. Their onstage work had the same dynamic, from what I’ve seen.

I don’t think Yoko broke up the Beatles, but I think she did work to keep John and Paul apart in the 70s, and that the Lennon/McCartney partnership still rankles with her. One of the ridiculous things about the Mozart/Salieri crack is that Lennon and McCartney were fundamentally collaborators, not competitors. But it’s in Yoko’s interest to present them as competitors, and to present herself as John’s collaborator.

In re: Yoko’s treatment of Linda McCartney during her final illness. Yoko presents herself as the grieving widow, which in a way was the best thing which ever happened to her — there’s considerable evidence that she and Lennon were on-and-off the rocks a lot, and she was able to sanitize the details of their relationship after he died. Can you imagine what Lennon would have said about Yoko had they broken up, given how hard he was on McCartney?

Yoko has rewritten history to the point that nobody remembers that she met John through Paul, having gone door to door to famous musicians in 66, asking for manuscripts which John Cage could use in a book. Yoko went on to stalk Lennon for more than a year, standing at the bottom of his driveway in all weathers for entire days, while Lennon told Cynthia “she’s a nutter.” Yoko would even force her way into their limousine. John did not wander into the gallery, see her “Yes” postcard on the ceiling, and fall madly in love with a kindred spirit.

But who cares, right? Lennon had every right to love whom he liked, even if he chose Yoko over the Beatles. (See the infamous video of John and Yoko on stage with Chuck Berry, where in the middle of Johnny B. Goode, Yoko starts her yodel-shrieking — Chuck’s eyes bug out of his head, but John just goes on smiling and strumming as if to say “please, dear god, just put up with her, that’s what I do”.)

If that made him happy, whatever. But it needs to be said that Yoko was not very generous to the rest of the Beatles; she used appearances with Julian Lennon at the RR Hall of Fame induction to make her look like the matriarch of the clan, when you can tell from his body language (and his words afterward) that he loathed her and wanted no part of it. What she left unsaid at that time was that she blocked John from seeing Julian when Julian needed his dad, she denied Julian his own mementos of his father — and everyone gave her a pass, because you know, grieving widow.

I think that if you’ve been through what Yoko’s been through, you should have learned compassion and how to bury the hatchet. But at these times we see the Iron Lady under the white robe.

@Sir, I think what we see occasionally in Yoko is the trauma of the refugee. We don’t really know what she had to endure during the War, but I suspect a lot of what comes off as cruelty or hardness is something like PTSD. (Not that I’m excusing it, just that it’s obviously so peculiar.)

I agree, Nancy. In that Rolling Stone interview, DeCurtis even asks Paul what it would take to switch the credits, and he says all it needs it Yoko’s approval.

Now, that’s not to say that I entirely agree with Paul on the issue. I understand that the original agreement, at least in his eyes, may have been switch back and forth (and John didn’t complain when it was done so on Wings Over America) but Lennon/McCartney became too powerful a brand to do that. And whatever my personal feelings regarding Yoko and her treatment of Lennon’s legacy are, I don’t think that she (not party to the original agreement) should necessarily change the arrangement that she was aware of as long as John was alive, just to please Paul. Although Paul says it was just for “Yesterday” only, I don’t think it would stay that away, and there’s something to be said for not opening the can of worms where they sit down and try to determine which is a Paul song vs. John song just to switch the credits on everything. I don’t think that would be possible in terms or time or money.

My favorite period of Paul’s career is what I like to call the Second McCartney Era, from 1995 (the Anthology) to the present (1970-80 being the Wings Era, and 1980-1995 being the First McCartney Era, my least favorite) so I’ve studied it a lot in addition to living it. I remember the fan and media outcry when the credits were switched on Back in the U.S. It seemed out of character to some people, for Paul to do something so brazen without apparent legal authority. But there have always been certain emotional triggers for Paul, and Linda is definitely one of them, and I think the Back in the U.S. was Paul definitely being angry at Yoko over her treatment of Linda, which caused him to act somewhat irrationally.

@Rose, if there’s somebody acting irrationally in this issue, it’s Yoko, not Paul. AFAIK there’s no piece of paper setting down the “Lennon/McCartney” arrangement; do you know of one? It seems like an informal agreement, a custom begun by two minors, the exact parameters of which were never set down. It may not be “Yoko’s approval” that was needed as much as “Yoko’s letting me know she won’t bring a frivolous but expensive and damaging lawsuit.”

As far as “Yesterday” in particular, John said in the Playboy interview of 1980: “Well, we all know about ‘Yesterday.’ I have had so much accolade for ‘Yesterday.’ That is Paul’s song, of course, and Paul’s baby. Well done. Beautiful– and I never wished I had written it.”

So it’s clear that Lennon claimed no credit for ‘Yesterday,’ and wanted none. Does this seem like someone who would object to reversing credits on it in 1996? Unlikely. And Yoko surely knew that. She surely knew that John wanted people to know who wrote what, because she was present during the interviews where he went through song-by-song. So why did she act against that wish, after his death? I’ll get to that in a second.

I don’t think the “brand” aspect matters much, as of 1996, and given the setting (the Anthology). It’s somewhat peculiar to call Lennon/McCartney a “brand” in the conventional sense of that term, 16 years after Lennon’s death and 26 after they’d split. But let’s grant that: would Paul’s reversing the credit on “Yesterday” really injure or confuse? Would it cost anyone money? How likely is it that a reasonable person would think “Yesterday” by McCartney/Lennon was a different song than the “Yesterday” credited to Lennon/McCartney? How does this injure John Lennon’s legacy, except to clarify it — to correct a misapprehension that drove him crazy and he himself said he wanted corrected? From the same interview: “I go to restaurants and the groups always play ‘Yesterday.’ I even signed a guy’s violin in Spain after he played us ‘Yesterday.’ He couldn’t understand that I didn’t write the song. But I guess he couldn’t have gone from table to table playing ‘I am the Walrus.'”

Finally, if Lennon himself did not complain, publicly or even privately, when McCartney did this on a handful of songs in 1977, then clearly reversing credits was part of the oral, informal agreement between the parties. So I don’t think it is a legal issue, and that’s precisely why Paul asked (“she couldn’t possibly care”); and why Yoko declined (“I won’t, and if he does, I’ll shit all over him in the press”); and why it rankled Paul so. If he did it over Yoko’s objection, he would (as usual) be perceived as insecure and hustling, and she would (as usual) be perceived by the world’s idiots and Jann Wenner as fiercely protecting her husband’s legacy. But how can anyone honestly believe Yoko treasures John’s legacy prior to May ’68? Has she ever done anything to celebrate John’s Beatle years without a pressing personal financial interest? What am I not remembering? She’s just not interested in “the mopheads or whatever” — except when she can needle Paul.

There’s a piece that is credited to my old writing partner and I, written totally by him, and yet credited in the way that we orally agreed all our work should be credited in magazines: “by Michael Gerber and Jonathan Schwarz.” When this piece was put into a collection of the best humor from The New Yorker, I asked Jon, “Do you want your name to come first? It’s your piece.” He declined; but if the piece is anthologized again and he wants to switch it, the only respectful thing to do is allow it. Because it’s Jon’s piece, and I want people to know he wrote it; I’m proud of him for it. John wanted people to know Paul wrote “Yesterday”; he was proud of him for it. Good, successful, healthy creative partnerships are like this. It’s only damaged, unhealthy partnerships that obsess over credit; John and Paul never had that squabble; it’s Yoko and Paul — unwilling partners, thrown together by business — that argue in this way.

“Yesterday” is Paul’s song, Lennon admitted as much many times, and while it would probably be petty for Paul to credit it solely to “McCartney,” “McCartney/Lennon” is both respectful to his dead partner, and more accurate. That reversed credit does what a credit is supposed to do: tell the audience who created the song. It has nothing to do with Yoko, except, perhaps, I’m guessing here, “Yesterday” is proof that history will remember JohnandPaul more than JohnandYoko. This is an old hurt, and understandable, but it’s really a shame that it can’t be laid to rest. Paul was John’s perfect creative foil; Yoko was the woman John loved. There should be room for both.

I’m late to the party on this one, but wanted to add that Yoko sees HERSELF as John’s perfect creative foil, hence the roadblocks.

I’ve always thought Lennon manipulated Brian Epstein to get John’s name first. A young Paul allowed himself to be talked into that … and regretted it for decades after. But as soon as Lennon was murdered and canonized, there was no way for Paul to “win” that credits issue without looking small. So he got screwed several times on this credit issue. Sure, that’s unfair to Paul but then sometimes life is unfair. Let it be.

As for Doyle’s book, I really really enjoyed this book. God it was SUCH a relief to read a book by someone who actually liked and appreciated Paul’s solo work, and who didn’t routinely assume the worst about Paul, or act all judgmental about Paul’s rather extensive love affair with cannabis. Nor did Doyle let him off the hook either for some of Paul’s more bizarre and sloppy decisions.

Questions I wish I could ask Doyle:

1. I noticed that, when asked about good bios of Paul, Doyle pointedly DID NOT include that atrocious Fab bio by that hack Howard Sounes. Guess you can tell how I feel about that book. 🙂 But I wonder what Doyle thought of it. Specifically what did he think were its biggest weaknesses? Personally, I think the Fab book fails because Sounes has no interest in Paul as an artist and no understanding of his music. But I’d like to hear why Doyle disliked the book. Also does Doyle expect Philip Norman’s forthcoming book on Paul (shudder!!!) to be anything but a hatchet job? There’s another example of a writer who doesn’t even like Paul’s music and thus is in no position to judge the best of it, let alone the worst of it.

2. Does Doyle really believe that story about John Lennon throwing 2 bricks through the window of Paul’s Cavendish house? How confident is Doyle that that actually happened?

3. What is Doyle’s favorite McCartney solo albums?

4. Why does Doyle think the British seem so inclined to disdain Paul? Why do the Brits like using Paul as a punching bag? I accept of course that sometimes Paul does and says dumb, dumb things. Don’t we all. But I find it interesting that the British are so hard on Paul for dyeing his hair or for his mediocre performance at the Olympics and yet they seem to love Dolly Parton lately, despite her having so much plastic surgery and botox she can’t move her face and despite the fact that she lip-synced and used backing tracks at Glastonbury? In short, why are the Brits so willing to cut Dolly some slack but not Paul?

5. I agree with Nancy that the 80s was a very bad era for Paul. He seemed to flounder artistically and at the same time in interviews from the era he seems so … angry all the time. And rumor has it that the late 80s was the period when Linda and Paul had marital trouble. So was it John’s murder? Was it all of the post-murder “John WAS the Beatles” bullshit? Or did Paul just struggle with how to belong in a music business that had changed?

The interesting thing about the 80’s is that Paul started on such a high note with Tug of War, which was widely critically acclaimed. Things definitely went wrong around the time of Broadstreet, which may be the biggest misstep of Paul’s career. There’s also the switch from EMI/Capitol to Columbia in the late 70’s, where IMO the different record company caused a change in Paul’s focus (for example, the alleged pressure from Walter Yentnikoff for Paul to collaborate with Michael Jackson). I think the combination of a new record company, John’s murder and the Tokyo bust shook Paul, but it’s really down to what those things contributed to: a lack of touring that decade. Paul has always seemed somewhat adrift without live performances, and the 80’s illustrated that lack of focus. It’s like without the feedback from his tours, he was unsure what to do. The 80’s also saw the problems of Paul’s eldest daughter Heather (hospitalized twice for mental issues) and rumored marital bumps with Linda, but those are things that most biographers avoid for understandable reasons.

As Doyle didn’t do a complete biography of Paul’s entire life, I wouldn’t expect him to address this, but I’ve always felt that no biographer has done justice to examining Paul McCartney’s background and childhood. Maybe because I’m a woman and have a different perspective, but it’s rather glaring that so many Lennon/Beatles biographers delve so deeply into John’s childhood and treat Julia Lennon as a Rosetta stone to understanding her son’s life. But aside from (weirdly enough) Bob Spitz, it doesn’t seem that Paul’s early life gets the same treatment. But Paul’s mother’s death had as big an impact on him as Julia’s death had on John (or arguably more) and was the defining event of his life, as he’s said himself many times. And from what I’ve of Mary McCartney’s life, I definitely think there are some clues about certain aspects of Paul’s personality. For example, it seems that many writers puzzle over Paul’s perfectionism and ambition. Yet he was raised by a woman who was apparently self-sufficient since she was a child (after her own mother died), was strong-willed enough to leave an unhappy home by herself at age 14, and was independent enough to forego marriage until her early 30’s in favor of her career. Then she became a working mother who was not only the typical caretaker, but the main breadwinner and financial provider. I don’t think enough writers have considered what role that early gender modeling had on McCartney’s life and his (somewhat unconventional, for a rock star) view of women.

Rose, I think you’re onto something with the influence Paul’s mother had on him. Combining domesticity and ambition is definitely Paul’s thing, and I agree that his empathy for women is striking when considered against the “typical” rock star view of them.

As for what happened to Paul in the 80s, I agree with you about the probable role lack of touring played. The “John WAS the Beatles” BS that Drew alludes to is clearly another part of the puzzle. I’d add that one of the few comments I found insightful in Howard Sounes’ biography of McCartney was that much as Paul missed John and George after their deaths, he was also relieved not to have them “snipe” at him in the press. I don’t think it’s possible to overstate the effect John’s death had on Paul. Besides being perpetually compared to John negatively, Paul no longer had John’s probable reaction as a brake on anything he did. I think Paul might have thought twice about “Broad Street” (which I agree is his worst career misstep) if John had been around to comment on it.

Another thing about Paul in the 1980s: he was 38-48 in that decade, and for a lot of people that’s a time of some reevaluation and life tension. Look at John in 1980, as he was turning 40. Besides dealing with the whole career question, Paul was dealing with more mundane issues that many middle-aged people negotiate—teenagers, a marriage in its second decade, physical aging. Add to all that how 80s musical trends brought out the worst in many musicians, particularly ones who became famous in the 60s or 70s.

Rose’s point about the influence of Paul’s mother — that combination of domesticity and ambition — is really fascinating. And yes, it’s absolutely puzzling why biographers who spend so much time on Lennon’s childhood traumas (for good reason) seem to think that Paul’s having his entire stable family life ripped out from under him at age 14 would have been no biggie. Even writers like Mark Lewisohn, who I always thought seemed fairest of all the Beatles biographers, in his book Tune In strangely treated Mary McCartney’s death as if it was no big deal. Lewisohn goes on at length about the impact of Julia Lennon’s death but Mary’s death and the effect on Paul gets something like 3 pages. Bizarre, and a typical tendency of male writers to spend time on the obvious (a 17 year old affected by a broken home and a mother’s death) while not taking the time to explore a more complicated issue in more depth (like the impact on a 14 year old, used to a happy, stable home, of losing this force of nature in his life). I guess it’s because McCartney didn’t scream about his pain in song?

One thing: Tug of War may have been critically acclaimed at its time of release, just as Double Fantasy was, but I think the praise for both albums was due more to sentiment and emotion after John’s murder, than to the quality of either album. Both albums have a couple good tracks but now, listening today, neither albums strikes me as all that great. The sound of both albums is what I call “adult contemporary mush.” Paul’s McCartney II album gets more respect from music reviews today (as it should) than Tug of War.

Thank you for the lovely replies, Nancy and Drew. This is obviously something I feel passionate about.

I think it points to a recurring problem with Beatles/McCartney biographers. Not many of them seem to want to scratch the surface. They go in with a predetermined image and fit the facts around it. So Jim McCartney was outwardly charming, had a love for popular music, etc. therefore his parental influence fits much more with most writers’ image of Paul as the cheery, pop loving, content one to John Lennon’s tortured soul, and so they look no further than father Jim and the happy-go-lucky McCartneys. Not that they weren’t a huge influence on Paul, but it ignores the more complicated family background and influence of his mother. We know that she was the one who was upwardly mobile, always working for a better house, a better neighborhood, a better school for her kids. She was the one who emphasized to her sons (according to Paul) that there was a better life outside of Liverpool and they should strive for more. Particularly in the 60’s, much was made of Paul’s ambition and restlessness, his “social climbing’ and keeping his eyes on the prize. He was more cautious regarding things like drugs but more concentrated on long term goals than a lot of his rock star peers. Where do they think that came from?

So many Lennon-centric writers knock Paul, as well, for emotional guardedness, but if they’d delve a little deeper, it doesn’t take a psychoanalyst to see where that might have originated. One of Bob Spitz’s interesting bits of research is that Mary McCartney was diagnosed with cancer originally much earlier than previously thought, when Paul was about 6. Spitz claims (apparently with Paul’s aunt as his source) that it went into remission and then re-occurred when Paul was 14. But he overall paints a darker portrait than other biographers, of a household where Paul and his brother lived with their mother’s illness but were never told what it was exactly, not even when it killed her. Do you think that maybe a child living under the shadow of something obviously terrible, but with all the adults around not addressing it, may have learn to built up walls and shut down in the face of emotional catastrophe? (A sad aside: Paul told Maureen Cleave that he only had a few possessions of his mother’s, one of them being a letter she wrote to a doctor who’d dismissed her health concerns, begging him to take her seriously. She felt something was deeply wrong, and it was, the breast cancer that killed her. A similar scenario would play out years later with Linda, who according to Paul was misdiagnosed by the first doctor she went to for her breast cancer.)

It’s not like the sources aren’t there, for those who want to dig. Paul’s circa ’67 comments to Hunter Davies for the Beatles authorized bio were quite blunt (that he swore off religion after her his mother’s death) and an autobiographical article Michael McCartney wrote in 1966, which emphasizes the severe depression and personality change Paul went through after their mother’s death. Again, despite the inaccuracies in his book, Spitz is one who seems to treat the subject with the importance it deserves. As for Lewisohn’s Tune In, I agree Drew, and I wonder if Lewisohn’s relatively close relationship with Paul made him hesitant to delve too deeply.

“(A sad aside: Paul told Maureen Cleave that he only had a few possessions of his mother’s, one of them being a letter she wrote to a doctor who’d dismissed her health concerns, begging him to take her seriously. She felt something was deeply wrong, and it was, the breast cancer that killed her. A similar scenario would play out years later with Linda, who according to Paul was misdiagnosed by the first doctor she went to for her breast cancer.)”

Oh my God, @Rose.

Comment threads like these are why we do Hey Dullblog. Thanks people. So interesting.

If I remember correctly Drew and Rose, Mark goes into a lot more detail about Paul’s mother’s death in the extended version. So it seems the editors are probably to blame for the chopped up account that appeared in the mass market version? Also great discussion as usual. This is such a fun blog.

Speaking of the Spitz book @Rose, doesn’t he also mention that Jim started drinking after Mary’s death? It’s been years since I read that book so my memory could be off. Also I believe Paul himself was interviewed for the book which suggests a degree of cooperation on Paul’s part which may explain why there is more detail about his family life than appears in other books. And the Mike McCartney articles that appeared in 1965: those are really interesting. So like you said the sources are out there but they are not being used.

@linda, there’s no mention of Jim drinking that I could see (I just went and took a brief look) though Spitz does write about Jim’s extreme grief, which other biographers have noted as well. I know it’s not the first time I’ve read that Jim actively threatened to kill himself after Mary’s death. It seems the family were concerned enough about Jim’s mental state to pull Paul and Michael from school and send them to live with one of their aunts for a brief period. Spitz writes that Jim’s depression lasted for a long time and he relied on his sisters to basically do everything, though previously he had been an involved father, often stepping in on domestic duties because of Mary’s erratic schedule and long hours.

I would love to know if Lewisohn expanded on Mary’s death in the extended edition of Tune In.

Thanks for checking @Rose. I didn’t get a chance to last night. Yes now I remember; what I mis-remembered as drinking was actually Jim’s deep depression and suicidal ideation. I don’t know why I thought it was drinking; my memory playing tricks again. But this is major information. It is boggling to me why no one else has expanded on this as well as other points Spitz made concerning Mary’s death and Paul’s childhood in general. I don’t think Spitz’s book was particularly great over all, but admittedly he did do an excellent job on the boys’ childhoods. I remember learning a lot about all four of them, that I hadn’t known before. I wonder if other authors perhaps stayed away from expanding on Spitz’s information because of his reputation for muddling so many facts. That’s a shame.

I pulled out my extended version of Lewisohn’s book and re-read the part about Mary’s death. It expands three pages compared to what I remember as only half a page in the mass market version. Anyway in the extended version Mark writes that by the time she was admitted to the hospital the cancer had already spread to her brain. Then he goes on to write the usual information about how Paul and Mike were told nothing. However he details how disoriented they were, being trundled off to their uncle Joe’s house for days and wondering why everyone was so subdued and uncle Joe wasn’t telling any jokes. Then of course Paul’s comment about the loss of Mary’s pay packet when they were finally told she had died is mentioned. But at least Lewisohn puts Paul’s childish (because he WAS a child) comment into the proper context instead of letting it dangle on the page with no explanation or context, like other authors have done. He also includes Mike’s comments about Paul’s personality change and depression in the aftermath of their mother’s unexplained ‘disappearance’ from their lives. Interestingly he also wagers using quotes from Mike, that if Mary had lived it’s quite possible that the Beatles may not have existed because she never would have allowed Paul to take such an unorthodox path. So Mark does go into some detail although probably not as much as Spitz. Certainly more than other authors, but still not enough for such a monumental, life changing event in the life of one of the subjects of this biography. It feels incomplete as if so much more needs to be said. However if my faulty memory can be relied on, I believe Mark does re visit the impact of Mary’s death on Paul, several more times throughout the extended version I.e. his attitude and attachment with certain girlfriends and his special relationship with older women in the Beatles’s lives, such as Vi Caldwell.

@Rose and @Linda, I too seem to recall a comment about Jim being (or becoming) a drinker. Such things stick in my mind, given my pet theory of The Beatles fitting into patterns commonly found in alcoholic families. But I don’t know where I read it — my Extended Lewisohn isn’t easily accessible at the moment, unfortunately.

@linda, thanks so much! It’s interesting that Lewisohn says Mary cancer spread to her brain. That’s the first time I’ve ever heard that, and is horrific is true. That’s a horrible complication.

This is what Paul told NPR’s Terry Gross about the subject in 2001:

“We knew that, for instance, we would have to talk to the kids about [Linda’s breast cancer] whereas, in the era I was brought up in, postwar Britain, it [his mother’s breast cancer] wasn’t the kind of thing that women talked about. And there were a lot of things that women didn’t talk about…I think there are still a lot of people like that, but it was particularly that way. So when she got ill, she just got ill. And when she went to hospital, she was just in hospital for a short while. And it was all not spoken about. And it wasn’t until much later that I learned that she had, in fact, died of breast cancer. So it was particularly chilling when Linda contracted it. And there were plenty of echoes that I actually tried not to notice.” [Paul gets choked up here and stops talking.]

Terry Gross: “What do you mean by echoes?”

Paul: “Um. All sorts of things. I mean, my dad… I remembered my dad saying to my mum, when she would get tired because of her illness, ‘Why don’t you go upstairs and have 40 winks?’ So that was something that I was very careful never to say to Linda, out of sort of superstition, you know. I just thought, ‘No, don’t ever say that. Whatever you do.’ So I would say, ‘Why don’t you take a nap?’ You know, that kind of thing. So there were all sorts of echoes.”

@Michael I remember in one book (I still think it might have been somewhere in Spitz but maybe not in regards to Mary’s death) That when the McCartneys had company Jim would keep filling their glasses and it was implied that he drank right along with them. However this is a vague memory desperately in need of citation. That is the only thing I’ve ever remembered reading about Jim drinking. That’s probably where my mind reconstructed things as Jim drinking in reaction to Mary’s death. But your comment about the Beatles fitting into patterns commonly found in alcoholic families is very interesting and has sparked my curiosity! Can you elaborate?

@Linda, this is worth a post of its own, but from the moment I was told of the pattern, I thought of the Beatles. Here’s some (edited) info from the University of Illinois Counseling Center:

HERO — These responsible children try to ensure that the family looks “normal” to the rest of the world. In addition, they often project a personal image of achievement, competence, and responsibility to the outside world. They tend to be academically or professionally very successful. The cost of such success is often denial of their own feelings and a belief that they are “imposters.” This is Paul, right? And that feeling of being an impostor is exactly what John used to get at him in the “How Do You Sleep?” years.

ADJUSTER–These children learn never to expect or to plan anything, and tend to follow without question. They often strive to be invisible and to avoid taking a stand or rocking the boat. As a result, they often come to feel that they are drifting through life and are out of control. George, certainly until 1966. And the one thing a strong spiritual practice gives is a sense one is no longer drifting through life. I quote: “Everything else can wait, but the search for God cannot wait, and love one another.”

PLACATOR–These “people pleaser” children learn early to smooth over potentially upsetting situations in the family. They seem to have an uncanny ability to sense what others are feeling, at the expense of their own feelings. They have a high tolerance for inappropriate behavior, and often choose careers as helping professionals, which can reinforce their tendencies to ignore their own needs. Also Paul, right? To me, the Hero role and the Placater are similar, if not the same.

MASCOT–These children are “entertainers,” relying on their sense of humor to distract from or take away the family’s upset. They tend to have difficulty focusing and making decisions, and have a low tolerance for distress. Ringo. The one all of them could always get along with.

SCAPEGOAT–These people are identified as the “family problem.” They are likely to get into various kinds of trouble, including drug and alcohol abuse, as a way of expressing their anger at the family. They also function as a sort of pressure valve; when tension builds in the family, the scapegoat will misbehave, allowing the family to avoid dealing with the drinking problem. Scapegoats tend to be unaware of feelings other than anger. And, of course, John.

It’s shatteringly obvious, once you see it. The inability of authors (especially authors from the UK) to acknowledge these aspects, preferring instead to pretend that group dynamics are mysterious and everybody drinks until blackout and of course John never killed a guy and what a wonderful series of coincidences!, has kept them arguing over minutiae rather than actually seeing these four guys as FOUR GUYS. Most authors, and most fans, don’t want to understand how the Beatles sausage got made, or J/P/G/R warts and all; they want to live inside a story they love. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it does put a hard limit on our understanding which I personally get impatient with, and am ready to move past.

@Michael, have you ever heard of the book The Beatles With Lacan? It was a rather strange, obscure little book that I used to have in the mid-90’s, but have long since lost. It took a psychobiographical approach to studying the Beatles, John and Paul specifically. I remember that some of the psychologist author’s contentions were a bit out there (too Freudian for my taste) but they were interesting nonetheless, and it was actually a very well-researched work in terms of their childhoods.

Anyway, one of the things that sticks out in my mind is that the author made much of Jim McCartney’s gambling habit, which has been mentioned by other writers only in passing. The author proposed that money was a significant issue in the McCartney household, and that’s one reason why Paul’s comment upon learning of his mother’s death wasn’t so strange. I think the author thought that Jim, being outearned by Mary, may have felt inadequate as a provider and so turned to gambling. Supposedly family members said Jim’s gambling was the only thing they ever saw Jim and Mary argue about. I also remember that the author thought it was very significant that the first big expensive present Paul bought his dad with his Beatles money was a racehorse. Paul expressed personal dislike for gambling, especially when done by his dad, yet at the same time used it as a way to get approval, which the author thought was very telling.

The hypothesis was that for those reasons Paul, throughout his life, has ascribed a psychological power and control to money in a way the other Beatles didn’t – and part of the conflict over the breakup was because of the different way Paul viewed money vs. the others. I don’t know if I buy it totally, but it’s certainly a very interesting way to look at the group dynamics surrounding the breakup and legal battles.

As for drinking, I wouldn’t be surprised. There were few acceptable outlets for male depression at the time, and drinking was one. But what you wrote about alcoholism reminded me of that Beatles With Lacan book, because many of the same traits found in children of alcoholics are found in the children of other addictions, like gambling. The author very much took the view that Paul was an “obsessional son,” a hero of placator type like in your listing.

I remember that startling revelation Paul made in one his Howard Stern interviews, that his dad “hit him sometimes.” It wasn’t the typical (for its time) corporal punishment like Mike wrote about in his books, of spanking little kids. The incident Paul described to Stern happened when he was 16 or 17 and his dad hit him across the face. Paul said he looked at his dad and said, “Go ahead. Do it again.” His dad was rattled by that and, according to Paul, never did hit him again ever. It was a strange anecdote, different from Paul’s usual hero worship of his father.

@Rose, I gotta read that book!

IMHO, any grand unified theory of psychology — be it Freudian, Jungian, Reichian, or Scientology — has to be mined for whatever resonances it contains for the reader’s life, with the rest being left. Otherwise, one is apt to “mistake the finger for the moon,” to use the Buddhist phrase I see all over the place these days.

Something to ponder: what was The Beatles, if not the world’s biggest gamble? Especially for Paul, who could’ve fit into straight society quite successfully? I’m not surprised that he hated Jim’s gambling… nor am I surprised that Paul wagered his entire life. The difference is that Paul could affect the outcome of his gamble. That’s simultaneously all the difference, and only a difference in degree.

As to drink and depression: alcohol consumption was and is woven so deeply into the fabric of UK society and culture that it’s probably more a question of everybody getting exposed to the behavior, and then those with a genetic predisposition developing an addiction. Does purely situational drinking lead to alcoholism? I don’t know. Maybe some expert can tell us?

@Michael, it is indeed hard sometimes to tell situational drinking from addiction based on the outside. Of course Heather Mills tried to paint Paul as a drunk in their divorce case, but she’s hardly a reliable source for so many reasons. Not least which is (I’ve read her book) she’s one of those people who is rather hysterically anti-drink and drugs (thinks pot is a gateway drug, for example).

I do know that there were some reports Paul drank heavily after Linda’s death. Most famously, he’s clearly sloshed at his solo Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction (video on Youtube). By his own admission, he’s in the past used drinking to excess as a way to cope with emotional upheaval (like the Beatles’ breakup). In some people’s eyes, that would make him an alcoholic, though clearly at stable times in his life (like now in his current marriage) he still drinks socially but it’s not a problem.

In thinking about that issue of gambling and money, I recalled a couple of recent interviews with Paul where he talked about seeing how money affected families and was a source of conflict in Liverpool. He never said it about his parents, but can we read between the lines?

There’s also this 2013 interview with Miranda Sawyer in The Guardian (http://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/oct/13/paul-mccartney-new-liverpool-nancy). First, when talking about how writers always go back to the same things in their lives, Paul mentions Charles Dickens “always going back into his father’s debt.” Then later, according to Sawyer, Paul starts randomly talking about his own father and how he left school as a child to support his family, but still emphasized the importance of learning. Then:

“He tells me a sad story about his uncle Harry, who, with his brother, had to go to the Bluecoat School, a live-in school for orphans, because his mum could only afford to keep her daughter. ‘So Harry and his brother never saw their mother except on a Sunday, where she came to the church service, and they weren’t officially allowed to turn around and look at her. Though they did.’ Harry learnt Shakespeare at Bluecoats, and used to recite it to Paul.”

Paul goes on to talk about how different it was later to learn about John Lennon’s family (where an uncle was a dentist) or Jane Asher’s (where everyone was highly educated and had private lessons and things). Sawyer then writes:

“This all comes out in a rush, at the end of our conversation. I wonder why. It’s like he’s trying to explain something. That learning is important, that practice makes perfect, that you can transcend your circumstances. None of us can become Paul McCartney, of course, but his aspiration to excellence is inspiring. Not embarrassing, but liberating.”

“In some people’s eyes, that would make him an alcoholic”

Not in mine, @Rose. Addiction is a very particular relationship with a substance or behavior which leaves distinctive marks on a person’s life and behavior. From the outside, Paul’s life and relationships don’t seem to have many of those marks… Well, let’s say the marks are generally lighter and more benign (slowness and sloppiness caused by pot) than the marks left in the other Beatles’ lives by their own use of substances. On the other hand, none of them ever got thrown in the clink for it. That might have been salutary, in John’s case? The stuff that really screwed John up (like heroin) was wholly enabled by his rock-star immunity from the problems faced by us little people (cost and getting busted), and he mistakenly thought that immunity extended to his own body.

I think that last bit is Paul explaining why he’s a culture vulture; why he wanted a knighthood; why he was always image-conscious, etc. Lennon could afford to blow this all off; that was yet another advantage he had over Paul.

P.S. When looking for some info on Tune In, I came across a review in the Guardian, and thought this passage was relevant. I didn’t know that “Twitchy” Dykins was an alcoholic who’d lost his license for drunk driving before Julia was killed:

[By the time Lennon was five, Julia’s partner was a waiter called John Dykins, an alcoholic. For the first time, a Beatles book goes deep into her death in the summer of 1958: a year-long driving ban for Dykins that led her to walk to a bus-stop near Mimi’s house, where she was run over by an off-duty policeman. “To my mind, she’d been killed instantly,” said Lennon associate Nigel Walley. “I can still see her gingery hair fluttering in the breeze, blowing across her face.”

Nine years later, Lennon wrote the beautiful song “Julia”: “Her hair of floating sky is shimmering/Glimmering, in the sun.” As Lewisohn says, he had always been silent about her death, but when he finally voiced his feelings via music, it was obvious that, for his entire adult life, the bereavement had been at the core of who he was.

There are other tragedies, more than would perhaps usually afflict four young lives. The death of McCartney’s mother, Mary – from breast cancer, when he was 14 – doesn’t get nearly the same level of attention here as Julia Lennon’s, which is surprising given its likely profound effect on him, hinted at but not explored. He remains someone with a carefully cultivated exterior, who tends to talk about his personal history in soundbites, and rarely gives the sense of someone who is troubled. But “Paul was far more affected by Mum’s death than any of us imagined,” said his younger brother, Mike. “His very character seemed to change, and for a while he seemed like a hermit.” McCartney said he quickly “learned to put a shell around me”, which is telling. “Paul was so ‘nice’ you couldn’t get close. He was like a diplomat,” one of their early associates tells Lewisohn.]

“Paul was so ‘nice’ you couldn’t get close. He was like a diplomat,” one of their early associates tells Lewisohn.

@Rose, I struggled with this for decades. It’s classic, classic behavior.

To me, that Twitchy was an alcoholic — and think of how much you’d have to drink, to have your license suspended in Liverpool in 1956! — makes it likely that Julia herself was involved in the addictive matrix. I’ve known the occasional civilian (ie, someone without addictive or codependent tendencies) to date an alcoholic, but it’s much much MUCH more common for both members of the couple to have addictive personalities, or be an addict/enabler pair.

Most authors, and most fans, don’t want to understand how the Beatles sausage got made, or J/P/G/R warts and all; they want to live inside a story they love. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it does put a hard limit on our understanding which I personally get impatient with, and am ready to move past.

I agree. I get impatient with it too. That is why so many biographies are so mediocre at best, and don’t hold up to even a second reading. These traits that you have listed; I wonder if they would apply to a just a non alcoholic, dysfunctional family as well. I have always seen the Beatles as a somewhat dysfunctional family especially after 1967. I have seen the traits you have listed applied to the Beatles before but only as dysfunctional rather than alcoholic. That said, I think biographers and fans alike have skirted around the issue that a lot of their dysfunction, perhaps even all of it, was fueled by drugs and alcohol. Most people discuss their dynamics as if they were part of their natural personalities rather than the result of years of alcohol and drug abuse.

Lastly when you mention John killing someone, are you referring to the rumored beating he gave Stu that allegedly resulted in his death? For what it’s worth I don’t know whether or not this alleged beating ever occurred and even if it did, according to the medical professionals within the Beatles fandom, it isn’t medically possible that a beating would have caused Stu’s death because too much time had elapsed between the alleged beating and his actual death. I’m not in denial that John could be capable of inflicting such harm on someone. Perhaps he was. The beating he gave to Bob Wooler is evidence of that. But regarding the alleged Stu incident I just don’t think there is enough or any real evidence that John did anything physical to Stu at all, let alone something serious enough to cause death. Is that even what you meant or am I just babbling?

@Linda, I’m running getting ready for Beatlefest, but quickly:

There’s no hard, bright line for me between a dysfunctional arrangement and an alcoholic one. Alcohol (or pot, or heroin, or obsessive work) is simply a mechanism. Singling out the substance, or even the behavior, without addressing the underlying psychology — all the relationships — is like chopping the head off a dandelion and being amazed when it grows back. (They do that, right? It’s been years since I’ve had a front yard!)

I was referring to Stu, sure; but also the rumored drunk. And you bring up Wooler. The important thing, for me, is to realize that John Lennon wasn’t just your garden-variety yobbo. He had a definite rage and violence problem, which grew appalling when he drank — and we shouldn’t ignore that, or explain it away, or (most of all) take his word for it that he was suddenly all better. While Goldman’s portrait seems exaggerated in the other direction, I think the majority of Beatle fans choose not to deal with this aspect of their hero; which is OK if you’re 12. But if you’re doing it at 45, I think it’s time to dig a little deeper. Because John himself really did value truth; and suffered a great deal of psychological pain precisely because people refused to let him be a 3-D person after 1962 or so. And because using the life and lessons of Lennon to address one’s own challenges is a lovely way to honor one’s hero.

Paul was so ‘nice’ you couldn’t get close. He was like a diplomat,

Everybody says this about Paul. I once read a book about the psychological/social development of children and teens who lost their mothers in the decades before around let’s say 1975 which is probably around the time when society began to change their attitudes about death and children. Hundreds of men and women were interviewed and just about every one of them said the same thing; that after their mother’s death they “learned to put a shell around” themselves and they would never let anyone get close for the rest of their lives. Quite a few of the people interviewed didn’t even marry. Paul married but I’ve always found it telling that he only seemed to fall deeply in love with women whose mothers had died when they were young.

So Mark Lewisohn went from 1.5 pages on the death of Paul’s mother (in the “short” version) and a whopping 3 pages in the “extended” version. Meanwhile the impact of Julia Lennon’s death got 20 pages. I still don’t get why so many Beatles writers go on and on about the obvious (John’s unstable upbringing) and avoid analysis in Paul’s more complex case. It was particularly disappointing to see such cursory treatment in Lewisohn’s book since it was supposed to be the most detailed yet. Bizarre.

I share your frustration, @Drew, and after my weekend at the Fest (more about this soon), I have a guess why: most writers are terrified to have TOO much of their own opinion about the Beatles, because they’re afraid the fans won’t buy their book. There is no risk, and great drama, in rehashing Julia Death Porn. But to dig into Paul’s mother’s death, there’s a real possibility that you’re discover something at cross-purposes to the McCartney Happy Chappy meme — and fans might not want that. Why risk it? Just stick to the standard narrative, and throw in a few nuggets for the press release. Lewisohn’s the only one I really trust to go wherever the data leads him.

You can see this most clearly in how people talk about John and Yoko; any deviation from the Ballad is automatically not acceptable discourse — it’s automatically anti-feminist, racist, etc — and as ever, what people feel they cannot say is interesting to note. I was listening to a panel discussion on Saturday where a fan had the temerity to state a fact we were discussing last week in this very thread, that “Yoko didn’t allow Paul to change the credits on a few songs in 1996” and Steve Marinucci, the web’s foremost Beatle journalist said, “Don’t believe everything you read in the media.” Which, with all due respect to Steve, is an unhelpful, obscuring thing for a journalist to say. Either there’s more to the story, which he should tell us (it was 18 years ago, for God’s sake); or there’s not more to the story, and he’s lumping a statement of fact with anti-Yoko crap we all agree is unfair, and really hasn’t been common after December 9th, 1980.

Paul’s still the great undiscovered country of The Beatles; I suspect he always will be. I think Norman’s book is going to add another layer of distortion, which is exactly what we don’t need. Maybe Lewisohn will repair things, at least until 1970.

@Michael Gerber I seem to recall you mentioning maybe you’d do a separate blog post on how Paul, and the other Beatles, seemed to fit into these roles people who grow up with addicts do that you covered in some your comments here. Did you ever do it? I’ve never come across it if you did. I’ve been Beatles obsessed for decades now and specifically Paul McCartney within that and some of what has been mentioned here and a couple other comments threads I’ve seen, never even crossed my mind, about perhaps his father having a gambling or drinking problem or even about the hitting.

I have to be honest I’d always just thought of it in the “well that was normal in those days, corporal punishment was more common” sense but reading here pointed out the ways in which maybe this was a little more than the “normal” you might expect in the 50’s with corporal punishment. When pointed out it seems a little obvious yet it’s not something that I’d considered as a possibility.

I know it’s just speculation but it’s interesting to consider and something even I, who was always looking for more depth than we generally ever get about Paul in any kind of biographical context, hadn’t thought of at all. I just thought if you’d ever done that blog about it, I’d have been interested in reading everyone’s comments on it if I could get a link to it.

I don’t think I ever did, @MG. There’s a half-written post in the blog somewhere. Perhaps I’ll refurbish it and put it up.

@Michael, yes, it must be frustrating for Paul to have to live with John’s “working class hero” persona (which even John admitted was bullshit). Paul has always paid close attention to financial details in the way people who didn’t grow up with a lot of money often do. But John often had a laissez-faire attitude about money. It’s not that he grew up rich, but pre-fame, he was always supported by Mimi financially and allowed to indulge his hobbies, etc. in a way the others were not. For all the personal conflict with Mimi, she apparently never pressured him to get a job and still bought him guitars, etc. and he was never afraid of being kicked out or not taken care of. I don’t think John Lennon ever had a job in his life aside from musician and singer/songwriter, did he? And Mimi was comfortable enough to own her own home in a nice area of Liverpool, making an income from boarders, not working (even after her husband died) and supporting a growing boy.

I’ve seen fans get annoyed when Paul emphasizes things like the $200 (or whatever it was) that John got for his 21st birthday, or having an uncle who was a dentist, etc. To them it’s not a big deal and Paul trying to dig at John’s working class hero persona, and maybe that’s part of it. But I think the point is that, to Paul, it showed how John had a bit of a different life, despite their similarities. Paul had to get a job when they got back from Hamburg because his dad couldn’t afford to just support him while he moped around. Paul’s relatives were people like his uncle Harry, who grew up in an orphanage and became a laborer, not people who had access to white collar professions like some of John’s extended family, and Paul would never get something like a cash gift for his birthday.

Paul married but I’ve always found it telling that he only seemed to fall deeply in love with women whose mothers had died when they were young.

Not just that, but women with mothers in their lives, or mother figures. A huge appeal in his relationship with Jane was treating Margaret Asher as his surrogate mother, ditto with Iris and Vi Caldwell. Linda’s mother died when she was 20, so not a child, but according to their daughter Mary it was a big bond between Paul and Linda, and Paul of course was attracted to the fact that Linda was “womanly” in his eyes, because she was already a mother.

I don’t remember much of the details of Heather Mills’ life, except her mother left the home (to be with another man) when Heather and her siblings were children, and only died much later. But I almost feel that HM was such an anomaly in Paul’s life for various reasons anyway.

Nancy, his current wife, lost her mother in adulthood. According to reports her mom died of breast cancer in 1991, when Nancy was 32. Nancy herself was diagnosed with the disease quite young, at 35 and when she had a 3 year old son herself. That she battled breast cancer at the same time as Linda, and was a fellow patient at Sloan-Kettering who knew Linda, is what brought she and Paul together initially. Supposedly loss also further deepened their relationship when Nancy’s brother died in March 2008 and, a couple of weeks later, Paul’s surrogate brother Neil Aspinall died, and they helped each other through their grief.

It always grates on me that Paul carries on about John getting “alot” of money for his 21st birthday.

This money came from his mother’s will–each of her children were to inherit this sum of money when they turned 21. John’s sister Julia Baird even told Paul this, when she interviewed him a few years back.

Why does it “grate”? In a way it being from John’s mother’s will sort of supports the point even more. Otherwise maybe it was just a generous uncle or cousin who liked to hand out money to lesser off relatives on special occasions, but this was his mom,Julia, who hadn’t really moved up in the world at all, was able to leave her children 100 pounds each in her will. This would appear to show that John’s family was on a somewhat higher level than the rest of them. I may have missed it but I’ve never heard that Mary McCartney, who worked hard all her life, was very responsible and was relatively well educated being a nurse, was able to leave her children a comparable sum.

I’m commenting late (as always!), so this may fall on deaf/no ears… But Lewisohn says the 100 pounds was a coming-of-age gift from John’s Aunt Elizabeth in Scotland. Maybe that’s what John said at the time, whether true or not.

If Julia told Paul only a few years back (from 2015) that it was from their mother, could it be the first time he heard that? Has Paul told the story since then?

As for Julia having enough money to leave an inheritance, I vaguely recall there being an insurance policy.

I suppose there could have been two different chunks of money. When I was reading Lewisohn, it seemed like John and George were each getting a new guitar at every turn while Paul was still plugging the lead of his broken guitar into his pocket.

What I really wanted to know as I was reading Tune In was if each of them was getting more cash each week on that first trip to Hamburg than either George’s or Paul’s dad made and their digs were free (you’d have to PAY me!), where did Paul’s money go?

Laura, re: where was Paul’s money going, that is interesting and I’ve wondered the same thing. Do you think Paul gave some (or all) of it to his dad?

In Tune In, Lewisohn mentioned that they all may have sent money home so it’s certainly possible.

About the 100 pounds used for the trip to Paris, I just happened across a bit of audio where John is telling Eliot Mintz that it was a birthday present from a relative. So… I don’t know why his sister says it was an inheritance, but I can see why Paul has said it was a birthday gift.

Thanks for the clarification @Rose on the ages of their mother’s deaths etc. I knew Linda was 20 when she lost her mom…not a child but still, I think very young to lose your mother and in such a horrific way. I didn’t know Nancy was 32 when her mom died. For some reason I guess I assumed she was much younger. As for Heather Mills, I could have sworn her mom died of breast cancer too but I may be wrong on that. Anyway, I still think it’s telling that he only seems to fall in love with women who lost their mothers and in Nancy’s case, loss in general seemed to permeate their relationship. As you say not only did they both lose their mothers to breast cancer but they also bonded over the loss of Nancy’s brother and Neil Aspinall and the relationship seemed to reach a higher level after those deaths. It seems to me that loss through death is a major issue in Paul’s life, almost a defining part of his personality. It’s also interesting that when he was with someone whose mother happened to still be alive, he would bond with the mother and she would be as important as the girlfriend.

As for John’s attitude toward money vs. Paul’s, you make some great points here. I agree that John was somewhat indulged by Mimi, while Paul was not indulged very much at all. But I do want to just say that according to Lewisohn, at some point John wanted to upgrade to an electric, Hofner guitar that he’d had his eye on but Mimi actually did put her foot down and told him that if he wanted the guitar he would have to get a job. He got a grueling summer job breaking ground on some construction sight that was so far from his house, he had to get up at dawn and take two trains, then a bus, then walk the rest of the way. He hated it but he did stick the job out until he had enough to buy his guitar. He also claimed to have worked at a restaurant near Liverpool airport, where he used to “spit in the sandwiches”, but he may have just been joking.

@linda, that’s fascinating about John’s summer job, and the first I’ve learned of it. I admit, it raises him up a bit in my eyes. Those late teenage years of his are always treated as a parade of drinking and mischief, it’s nice to know that he did have a bit of the taste of “real life.” That it was hard labor is rather surprising, too; John was, by his own admission, quite lazy and hated anything that required a lot of physical effort. Good on ya, Johnny.

As much as I would prefer to pretend Heather Mills just doesn’t exist, I did go and look up the details about her mother, who died when she (Heather) was 18. It wasn’t cancer, it was from a blood clot after surgery to repair damage on her leg from a car accident years prior. But still, quite young, and actually Heather’s childhood interestingly enough resembles John’s a bit (mother left home for another man, she reconnected with her mother at about age 15 when she moved in with her and her stepfather, her mother then died of car accident-related injuries three years later).

Re: Nancy Shevell. 32 is still fairly young to some people to lose a parent. Not much is known about Nancy, but clearly she felt close to her mother, as she named her son after her and also runs a charity in her name. She also has quite a strong maternal figure in her cousin, Barbara Walters, who has said she considers Nancy her second daughter. Paul has apparently become somewhat close with Walters as well due to that. So it does fit the pattern. Though I would guess not as strong as a bond as Nancy having gone through breast cancer herself, and alongside Linda, which seems to be what Paul said bonded them so deeply and so quickly.

I find Nancy quite remarkable, to be honest. The way she (to quote Paul) lets Linda be a presence in their relationship, with no jealousy, seems to be quite liberating for Paul, and to have let him finally heal to some extent. And the way his kids seem to adore her is also quite lovely.

Heather’s childhood interestingly enough resembles John’s a bit

This should surprise no one.